World of Their Children

Joshua Leifer’s much-anticipated new book made an even larger splash than originally expected when a Brooklyn bookstore employee cancelled a scheduled event at which Leifer would have been interviewed about his book by—a Zionist! The story went viral. A week later, the bookstore had apologized, its employee was out of a job, and Leifer was celebrating the sudden metastasis of his audience and his book sales. He’s ready, he said, in his rescheduled conversation with Rabbi Andy Bachman at the Center for New Jewish Culture, to send his canceler-benefactor a fruit basket.

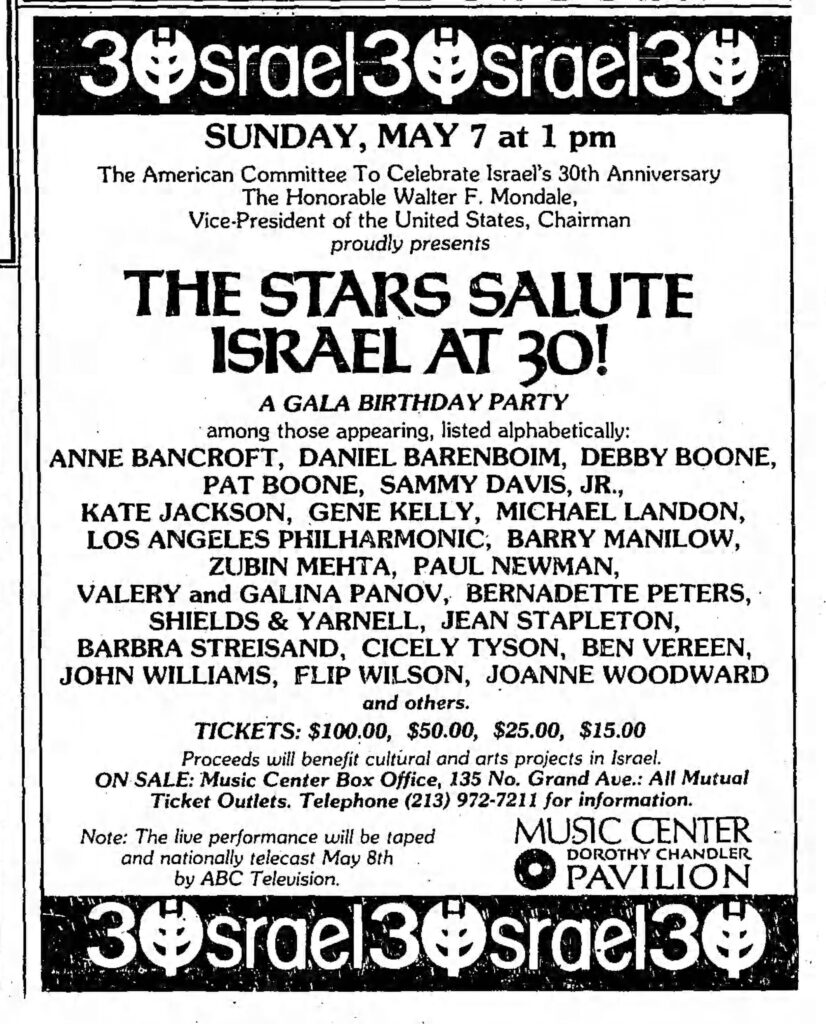

Leifer seems at first glance to owe a comparable debt to Franklin Foer, who appeared to set the stage for his book in a widely discussed article in The Atlantic this spring on the passing of the “golden age” of American Jewry. That era had begun, Foer wrote, when “anti-Semitism faded and American Jewish culture exploded in a rush of creativity,” after World War II. Among this culture’s chief representatives, he mentioned highbrow novelists such as Bellow, Roth, and Malamud as well as popular entertainers such as Mel Brooks, Elaine May, and Woody Allen. “In the Golden Age,” Foer added, “Jews in America embraced Israel.” And not just the Jews. In 1978, ABC aired a spectacle titled The Stars Salute Israel at 30, which ended with Barbra Streisand singing “Hatikvah” to an audience of 18.7 million viewers.

But Foer and Leifer don’t really see things the same way. Leifer agrees with Foer that the postwar period witnessed a decline in antisemitism, but he argues that it was chiefly marked “by mid-century embourgeoisement and suburban anomie, when a cultural and religious crisis appeared imminent.” This crisis was averted, he explains, not through high or pop culture, and certainly not by moribund American Judaism, but by a turn toward Israel. Zionism anchored American Jewry in this far from golden age but at a high moral price, Leifer argues, and one that can no longer be sustained.

When Leifer, a gifted journalist, Yale graduate student, and precociously young member of the editorial board of Dissent, speaks of “embourgeoisement,” he does so with a certain measure of disdain. But that doesn’t mean that he uniformly celebrates what preceded it, either in the Old World or the New. His quick sketch of the Eastern European environment from which most Jewish immigrants stemmed is far from nostalgic, nor does he romanticize their main destination, the Lower East Side, where, as he strikingly puts it, “the pious and the sinful walked through the same muck.” But this impoverished subculture—what Irving Howe famously called “the world of our fathers”—gave birth to an admirable working-class society, one “anchored in the garment unions” and inflected by Old World radicalism. “It provided . . . an elemental safety net, a social services network—a community. It spoke of universal concepts—class struggle, the emancipation of the worker, the liberation of mankind—in the language of Yiddish secularism.”

All of this was, however, doomed from the start, not on account of its enemies but by its very standard-bearers, whose bourgeois aspirations combined with their yearning to become fully American subverted their idealism. The Jewish working class “abolished itself through prosperity,” Leifer writes, adding:

It was a slow but simple transition: the abandonment of left-laborite commitment for embourgeoisement and conformity. It was the product of intention—no Jewish worker hoped that his son would take his place on the sweatshop floor—even if the effects were unintended.

Leifer argues that this rise “from the sweatshop to the suburb” was less than fully self-propelled. American Jews were able to follow this route “in large part because an array of public institutions” gave them the needed boost. “If the institutions of the Jewish labor movement accounted for one half of the real American Jewish success story, the emerging social safety net of the New Deal accounted for the other.” This historical reality, Leifer maintains, has been obscured by what he dubs the individualistic “schmatte-to-success story.” He identifies “a Jewish version of Horatio Algerism” that “had begun to eclipse the Jewish socialism that made its existence possible” in the 1940s.

In a sense, “Horatio Algerism” was Jewish from the outset. Alger himself tutored the wealthy banker Joseph Seligman’s children in the 1870s, before he wrote his famous rags-to-riches stories, and he may have been inspired by his employer’s experiences. Seligman, in any case, belonged to the class of German-born American Jewish philanthropists who immigrated to America with little or nothing, became wealthy, and made massive contributions, from the end of the nineteenth century onward, to the welfare of the Eastern European Jewish immigrants who came after them. These “uptown Jews” deserve at least a small share of the credit not only for their own successes but for the elevation of the “downtown Jews” into the middle class.

And what about the Eastern European immigrants who weren’t wholeheartedly proletarian? Even among the generation that Leifer admires, plenty of immigrants harbored “seemingly contradictory impulses toward working-class militancy and ambitious entrepreneurship,” to quote the historian Daniel Soyer. They weren’t just waiting for the next generation to get off the sweatshop floor but trying to do it by themselves and often enough succeeding.

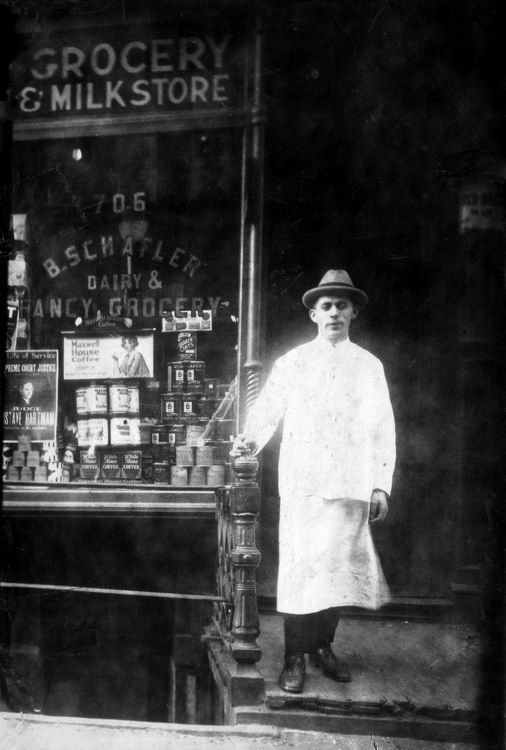

And what about all the Jewish store owners, restaurateurs, businessmen, and, yes, schmatte dealers among the Eastern Europeans who made their fortunes—sometimes small, sometimes vast—without ever studying at City College, or unionizing the shop floor, or even being direct beneficiaries of the New Deal? It wouldn’t be hard to list enormous numbers of them, and to describe their role in advancing their community’s prosperity. One might begin, for instance, with the families and (realistic) fictional creations of Foer’s list of postwar American Jewish luminaries. What of Saul Bellow’s tough-guy businessman brothers; or Bernard Malamud’s saintly shopkeeper in The Assistant; or Philip Roth’s father, the insurance salesman; or, for that matter, Woody Allen’s family delicatessen?

Leifer also omits the early history of the Zionist movement in America from his narrative. He is, of course, right to say that Zionism “only became a dominant fact of American Jewish life in the years after Israel’s founding in 1948.” But he is wrong to overlook the ups and downs of American Zionism between the days of Herzl and the birth of the State of Israel, including such pivotal developments as Louis Brandeis’s transformation of the movement into a powerhouse during World War I and the mobilization of American Jewry in support of the creation of a Jewish state between 1942 and 1948.

On the basis of his account, it would seem that American Jews paid scant attention to Israel before the Six-Day War. But then “everything about American Jewish identity changed in the flash of an Israeli Mirage fighter jet scraping over the Sinai Desert,” as Israel quickly and decisively defeated Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. “In the United States, Jewish pride in Israel—tough Israel, victorious Israel, strong Israel—swelled,” Leifer notes sardonically, “into expressions of ecstasy and euphoria.” That this victory was achieved over three neighboring states threatening to “drive Israel into the sea” goes unmentioned.

Leifer intertwines much of his historical narrative with personal recollections, but he wasn’t yet born at this time and can’t do so for the 1960s. I was, and my own memories don’t align very well with his reconstruction of events. The euphoria in June 1967 wasn’t just a burst of jingoistic glee at the sight of Jewish jets. It had much deeper causes than that.

Leifer underestimates, to begin with, the extent to which the Holocaust was on American Jews’ minds at the time. He says nothing at all in his book about the impact of the horrifying testimony in the nationally televised Eichmann trial in 1961, but he does mention the controversy over Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem—situating it “against the backdrop” of the 1967 and 1973 wars, when, of course, it preceded them by several years. The “flood of Holocaust films and TV specials” highlighting “the existential dangers from which the Jewish people had only recently escaped” and the degree to which Israel rescued it from its plight also began earlier than Leifer thinks.

When I attended Hebrew school and Jewish summer camps, in the early and midsixties, we saw our fair share of those movies (especially on Tisha b’Av). And even Jews who didn’t have any such experience were likely to have read Leon Uris’s bombastic but influential 1958 novel Exodus or seen the movie based on it two years later. Eichmann, and Exodus, and concern for their own relatives and friends in Israel were foremost in the minds of large numbers of American Jews in May and early June of 1967 as they watched the siege of Israel grow more threatening and read about bloodthirsty marches through Arab capitals calling for its annihilation, while the world failed to come to Israel’s aid.

I remember well how more than a thousand deeply worried people congregated in the social hall of our synagogue in the evening of June 5, 1967, who roused themselves to volunteer unprecedented sums for Israel. I know that what they (and others like them all over the country) were soon to feel was not merely a burst of pride at the exercise of Jewish might but an almost incredulous sense of having this time finally escaped the noose. Older Jews today, as Oren Kroll-Zeldin observes in his new book, Unsettled: American Jews and the Movement for Justice in Palestine, “have vivid memories of the perceived imminent destruction of Israel during the wars in 1967 and 1973.” Leifer is simply incorrect when he writes that “unlike the 1967 war, the war in 1973 alerted American Jews acutely to the precariousness” of the Jewish state.

Leifer himself, who was born in 1994, grew up in a place where feelings for Israel were even stronger than they were where I grew up forty years earlier. “Like many American Jews,” he tells us (though we should note, it’s really not that many), “I was raised in a traditional Jewish community where Israel was the spiritual and geographic center of the universe.” At his day school in northern New Jersey:

We learned that Israel not only constituted the Jewish people’s rebirth out of literal ashes but also exemplified the only reasonable response to the Holocaust’s most fundamental lesson: that the Jewish people must be prepared to fight if we are to survive.

The Judaism that he imbibed at home was fully in sync with Jewish nationalism:

At home for Shabbat dinner on Friday night, my sister and I would recite the blessings over the bread and wine in our best approximation of Israeli-accented Hebrew. For her bat mitzvah, we traveled to Israel so that she could read Torah at the Western Wall and prayed with our hands pressed against the ancient stone blocks, which glowed pink in the early morning sun. A few days later a guide took us to a firing range where we learned to shoot Uzis and emerged awed by the display of Jewish power.

Leifer took this “mix of religion and nationalism” very much to heart.

He became, in short, just what his teachers wanted him to be—but not for long. His school wasn’t his only source of information about Israel, and what he read on the web transformed him:

Late in my teenage years, I broke with the Zionist dogmatism of my upbringing. I became enraged by my community’s open support for the occupation of the West Bank and siege of Gaza and its justifications for the brutality that this entailed. At first I tried to suppress my fury, but eventually, as a volatile adolescent, I ignited. I threatened to run away. I was forcefully asked to leave a Passover seder for calling Israel an apartheid state in a heated argument with close family friends.

Arguments at the seder table notwithstanding, Leifer was never the haggadah’s wicked son. He “still loved the idea of Israel” and decided that there was “no better way to begin reconciling my growing criticism of Israel’s government and my deep attachment to the place than to go live there.” So he spent his gap year at a premilitary academy in Tel Aviv, studying Hebrew and traveling the country, including the West Bank. He returned to the US to attend Princeton in the fall of 2013 as even more of a critic of Israel than he had left it.

At this point, Leifer says, he was tempted to do what other like-minded young Jews were doing. “They folded away their Zionist sleepaway camp T-shirts, buried their olive-green IDF hoodies deep in a box in their parents’ basement, and melted into the wider world.” But he couldn’t bring himself to join them. He had to remain involved in the life of the Jewish community, he writes, because he loved Jews and Judaism, and “when the people we love support something immoral, we have the responsibility to help them right the injustice they have helped cause.”

It is to this cause that the striking title of his book alludes: Moses smashed the first set of tablets in protest against Aaron and the people of Israel’s idolatry before the golden calf to save the very Torah inscribed on them. “If today,” Leifer writes, “American Jewish life and identity is shattered like the first pair of tablets . . . that may not be a bad thing at all.” What most urgently needs smashing, of course, is the American Jewish consensus on how to support Israel.

Leifer devotes a lot of space to his attack on the Aaron-like leaders of the main organizations of American Jewry, from AIPAC to the United Jewish Appeal. They are, he alleges, an unrepresentative “committed core” of leaders who have never moved beyond the simplistic dogmas that he imbibed as a youngster. Inspired by neoconservatives, proudly American yet simultaneously convinced that Israel “represented the central commitment and telos of Jewish existence,” these people have for decades given unequivocal support to the Israeli government’s harsh and oppressive policies. They have done so in eager cahoots with “American imperialism,” arguing that Israel’s interests and those of the US are always aligned. Their “moral myopia” has thus made them complicit in the creation of “the current undemocratic one-state reality in Israel/Palestine.”

Leifer follows up this familiar indictment with an account of a burgeoning new—albeit relatively weak—counterestablishment, one in which he himself has played a part. It consists of small groups of young Jewish activists who challenge the Jewish survivalists’ pernicious hegemony with a “cultural revolution.” Proud of their Jewishness but ashamed of Israel, and largely alienated from the United States, they set out to “create new forms of Jewish identity unwedded to Americanism and Zionism.”

Such young Jews founded new groups, such as IfNotNow (in which Leifer was active in his early twenties), and resuscitated old ones, such as Jewish Voice for Peace. Those who joined them sought “expressions of Jewish identity and community that were untethered from Israeli militarism and that could be harmonized with support for human rights and concern for Palestinian suffering,” and they made this known in protests in the streets of the US from New York to San Francisco. It all brings back memories of the better old days: “Perhaps not since the 1930s had a left-wing Jewish politics claimed such a presence in American life.”

Leifer is impressed by a number of Jewish experiments taking place around the country, including New York City’s Jews for Racial & Economic Justice and its message of “doykeit” (hereness, in Yiddish diasporist parlance, as opposed to the “thereness” of Israel); Never Again Action, which protested outside ICE detention centers; and an “openly anti-Zionist synagogue” in St. Louis and another in Chicago that replaced the prayer celebrating Israel’s Independence Day with a mournful prayer for Nakba Day. In general, he applauds “the new progressive activists” for offering “a Judaism that was all about social justice and robust spirituality,” not tribalism and nationalism.

And yet, Leifer does not himself yearn for an American Judaism that is all about doykeit. However justifiably alienated one is by Israel’s policies, he insists, it’s impermissible for American Jews to turn their backs on the country. He is particularly harsh in his denunciation of those contemporary diasporists who “make dismantling the state of Israel core to their putatively Jewish politics”:

They appear unconcerned by what Israel’s destruction, particularly if achieved through military means, might mean for Israeli Jews. Theirs is, perversely, a Jewish politics that revels in its callousness towards the lives of other Jews, whose ancestors happened to flee to the embattled, fledgling Jewish state, instead of the United States.

These Israeli Jews are destined, Leifer notes, to become the majority of the world Jewry by 2050. “The locus of the Jewish people’s historical drama is now there, in Israel, whether we like it or not.”

At this point, I expected to see Leifer join the long line of left-leaning American Jewish intellectuals who have sought to provide Israel with the counsel it needs. But he doesn’t do that. He declares that he wants “to beseech them—if necessary even to force them [Israeli Jews] through sanctions or conditions imposed on future U.S. support—to pursue justice and seek peace, instead of occupation and endless war.” (Apparently, American imperialism has its uses after all.)

Leifer also acknowleges just how deeply Israel has recently been dependent on assistance from the American “hegemon,” which he believes has entered “its last days” of power in the Middle East. Nonetheless, he seems relieved that that help was available after October 7, 2023—thanks, in part at least, one should not forget, to the “survivalist” American Jewish lobby he excoriates.

Admirably, Leifer also acknowledges that the reactions of many on the left to the events of October 7 revealed with disturbing clarity the extent to which antisemitic thinking had found a home “in my own political camp,” though I am less than sure that he has come to grips with just how long this has been the case. Nonetheless, in a widely read essay in Dissent, published days after the Hamas massacre, he called out n+1 magazine, the Democratic Socialists of America, and others on the left for their inhumanity in justifying or even celebrating mass murder. Although this seems to have led to his shunning in some radical precincts, Leifer remains very much a man of the left, as we used to say, and a stringent critic of Israel.

What Tablets Shattered provides in the end is not a road map for Israel to follow but an analysis of American Jewish options: “the dying establishment,” “neo-Reform,” “prophetic protest,” and “separatist Orthodoxy.”

Leifer’s assessment of the state of affairs in Reform and Conservative Judaism is a deeply pessimistic one and, I think, unfortunately entirely correct. He notes that over the last twenty years, more than one-third of Conservative synagogues and one-fifth of Reform synagogues have closed, and “the leaders of both denominations have begun to speak in barely veiled terms of looming, managed obsolescence,” and they are not wrong to do so. “The once vast suburban architecture of liberal Jewish life is becoming a mausoleum to a religious civilization that has now passed.”

Or, rather, a pseudoreligious civilization whose pretenses have long since been exposed. In their synagogues, “Jewishness today has become a creed to be professed rather than a practice. . . . Self-gratification and individual preference have supplanted commandedness and commitment to community.” At bottom, “it is this liberal-individualist mentality,” more than anything else, “that is responsible for mainline affiliated Judaism’s demise.”

“Prophetic protest,” which is Leifer’s rubric for the left-wing groups that he admires, is in better shape—but it, too, has deep flaws. For one thing, it “may not be prophetic enough. It is too comfortable in the rhythms of late-capitalist life.” It thrives mostly on social media, rather than in real lived communities. Prophetic protest’s deeper problem, however, is religious: “Because its use of ritual and liturgy is almost always in service of an urgent political action, it has no coherent approach or explicit commitment to religious observance.” There is no robust sense of Judaism that determines the course of their everyday lives. “They are radicals, but they are also liberals—in the private realm, they believe, anything goes.”

“Neo-Reform” is Leifer’s own coinage and denotes not some tendency within institutional Reform Judaism but efforts on the part of “ritual innovators and liturgical experimenters” who can be found within the liberal movements and outside of them. He means more or less the same people whom Shaul Magid has described as representatives of “post-Judaism.” They “aim to revise the tradition and its texts—to edit, rewrite, replace, or disregard any element that fails to fit within the contours of today’s social reality,” and “they reject not only peoplehood but also particularism.” These “neo-Reformers delight in intermingling Judaism with other traditions in strange and syncretic (and, sometimes, frankly ridiculous) amalgams of religious expression.” Despite the sardonic tone, Leifer describes the doings of some of these experimenters respectfully, but in the end he doesn’t see the point. If this is Judaism, he asks, “why not just be a Unitarian?”

The last of the four alternatives, “separatist Orthodoxy,” or haredi Judaism, is the one that a reader of a book by a radical Yale graduate student would least expect to see favored—but it is. Leifer knows it unusually well for a man of his background, mostly because he married a woman who grew up in Lakewood, New Jersey, the cultural capital of what its members call the “yeshivishe velt.” This “Haredi Judaism,” he writes, “constitutes perhaps the strongest and most viable alternative to the now fading American Jewish consensus. Orthodoxy will thrive long after the old mainstream institutions fade away.”

What about the so-called Modern Orthodoxy, whose distinctive claim is precisely that it is not separatist? Leifer mentions it here and there but doesn’t rank it as one of American Jewry’s major alternatives. Whatever he thinks of it (which is probably very little, on account of its close affiliation with Israeli Religious Zionism and the characteristic aspiration of its members to—like their Reform and Conservative counterparts—live fully integrated and successful American lives), it’s not really what he’s talking about when he speaks of Orthodox Judaism.

While he pronounces himself “jealous” of the haredi Jews’ faith, Leifer focuses mostly on their countercultural way of life:

While the crass materialism of secular life induces us to gratify our needs—whether through unearned affirmation (“treat yourself”) or as therapeutic salve (self-care)—the urge to self-gratification for the Orthodox Jew is an evil inclination to be combatted and repressed. Mainstream American ideology puts the individual at the center; for the Orthodox Jew, the center of life is Torah and, consequently, obligations to God, family, and community.

This is borne out by daily life in Lakewood. There is, of course, the fierce dedication to Torah study. And there is the way in which “the community practices a soft collectivism . . . more kibbutz than conventional suburb.” The “collectivism” he describes is actually less kibbutz-like than village-like:

There are gemachs, charity funds or free loan banks for almost anything. (Gemach is a Hebrew acronym for acts of kindness.) Not just money but ritual items like mezuzahs and even wedding dresses for brides. In Lakewood it is a norm, following the religious commandment, to give 10 percent of one’s annual income to charity. . . . These funds often go to the religious-social safety net, which also includes free food delivery for those who need it, free tuition for school, and apartments to stay in when a relative is in the hospital. It is a system that is far more generous than the American welfare state, and far more expansive than anything my leftist friends who talk about mutual aid could ever dream of.

Lakewood hasn’t vanquished American self-centeredness entirely, however, and Leifer eyes with suspicion the conspicuous consumption that has come with well-paying jobs and successful businesses.

Needless to say, Leifer knows that there are, in addition to creeping prosperity, many drawbacks to the haredi way of life, including its conformism, insularity, patriarchy, and homophobia. But instead of condemning Lakewood, Leifer asks himself an interesting question. Are these vices in fact separable from the collectivist virtues of the haredi world? He is genuinely unsure, but at least “for now, Orthodoxy, remains the only living Jewish alternative to liberal capitalist culture on offer.” Although this conclusion hasn’t led Leifer to move to Lakewood and don a black hat, it has had an effect on his life:

After years of excuses and half measures, telling myself I would get around to it one day, I began to keep the Sabbath and all other holy days in strict accordance with Jewish law, don tefillin each morning, and wear a kippah, as I had been instructed as a child in school. I have also been lucky that I found a partner to walk with me in a shared life lived with commanded-ness at its core.

What he doesn’t tell us, however, is very much about the theology underlying this alteration of his behavior. All he says is that “God, for me, has always been much more an awful absence, a commanding void, than the source of all things, of good, of life.” This kind of faith, I imagine, is one that very few of the readers of this book will envy him.

For all of his focus on Zionism and Israel, Leifer’s more fundamental concern is with American Judaism, which he wishes above all to wrench free from the liberal capitalist culture that he argues has weakened, if not ruined, it in all of its forms, with the partial exception of separatist Orthodoxy.

As supportive as he is of haredi Judaism, he doesn’t think, as he emphasizes at the very end of his book, that “embracing tradition means relinquishing important progressive commitments like feminism, anti-racism, or opposition to the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.” After all, as he “tried to demonstrate throughout the book, there are, in fact, many people committed to living out their progressive values, to fighting for them, from within the normative framework of traditional Judaism.”

In fact, this is more of a prayerful hope than something Leifer has actually shown about any significant number ofAmerican Jews, even of his own millennial generation. Commandedness may be at the core of life in Lakewood—not so much among his Jewish allies. But Joshua Leifer has precisely limned the nature of his own predicament as a young American Jewish intellectual on the left in this sometimes exasperating yet frequently insightful and elegantly written book.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Stuck in the Middle

Would American Jews be safer if they removed themselves from politics?

The Hasidim: An Underground History

David Assaf introduces us to Hasidic Rebbes who ride into small towns and take over. (If cowboys were Hasidim, this would be Deadwood.)

Trilling, Babel, and the Rabbis

Part of Trilling's mystique came from the way he seemed "to be a Jew and yet not Jewish."

ArtScroll’s Empire

How did a Brooklyn-based, Orthodox publishing house corner the market on religious texts in America?

David Brownstein

It seems to me that to contrast 'highbrow novelist' Philip Roth with 'entertainer' Woody Allen says more about the author's cultural prejudices towards differing artforms than it does about 'entertainer' Roth and 'film-maker and auteur' Allen.

Re'uven ben Shlomo

I would fall into the author's "dying establishment" category, in which I feel cozily ensconsenced in my Medicare years. The political Jewish organizations with which I am associated are AIPAC and the RJC. I do not wring my hands over the military response by Israel to the Arab terrorists and their supporters, but neither do I take joy in learning of the deaths of our spiritual cousins from the line of Ishmael. I'm grateful for reviewer Allan Arkush's detailed scrutiny of Tablets Shattered, in which I now realize I would have minimal interest. I am acquainted with, but not sympathetic with, young progressives in America and Israel who struggle with their loyalty and feelings about Israel, Judaism, and progressive politics, which have become intertwined with attitudes and beliefs about free market economies in the tortured logic of critical theory. As a son of two survivors of the Shoah (Lodz, Poland and Dubno, Russia/Poland/Ukraine), I long ago concluded that the progressive spirit of collectivism in the last century brought us the despicable and unforgivable horrors of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao. I can only wish young progressives and their generation luck as they sort out their intrapsychic conflicts and attitudes.

Gerald Sorin

Allen Arkush’s essay is clever and informative as usual. Reuven’s comment is dismissive of Leifer’s book without having read it. He is also faintly supercilious about Arab Muslim loss of innocent life. More important he says he is “acquainted with, but not sympathetic with, young progressives in America and Israel who struggle with their loyalty and feelings about Israel, Judaism, and progressive politics.” If I an 84 year old Jew, does not “struggle with

[ my] loyalty and feelings about Israel, Judaism, and progressive politics,” than I am left with Torah and prayer only. Enough for Reuben, but not enough for me. If Judaism does not have struggle at its center I don’t know how to define it.

solomon lax

Thanks for the review. I just ordered the book. It is amusing to see the romanticization of a fiercely competitive society where if one is not excelling as the best Talmudic scholar, one is striving to be a successful capitalist. The social network takes a lot of money to keep going, and the levels of tzedakah given exceed the highest marginal tax rate. Tight communal bonds are beautiful, but Lakewood is the farthest thing from a gentle commune you can imagine.