ArtScroll’s Empire

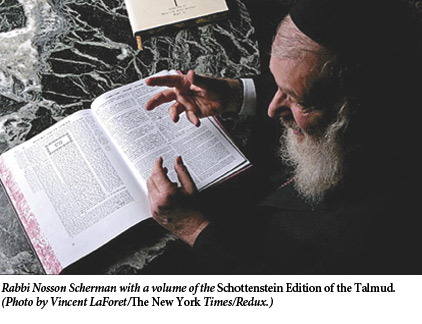

In February 9, 2005, a large crowd assembled in the foyer of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. to participate in a special dedication ceremony. Among the dignitaries in attendance were Jews from the left, like Senator Frank Lautenberg of New Jersey, Jews from the right, like Virginia Congressman Eric Cantor, and Jews from somewhere in between, like then-Democratic Senator Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut. The non-Jewish politicians spanned a similar spectrum, extending from then-Senator Hillary Clinton of New York to Senator Sam Brownback of Kansas. Dr. James Billington, the Librarian of Congress, presided over the ceremony, but the real star was Rabbi Nosson Scherman, the editor who is one of the initiators of what is sometimes called the “ArtScroll Revolution.”

Rabbi Scherman was there to donate to the Library of Congress a set of ArtScroll-Mesorah’s newly completed Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud, accurately described by Jeremy Stolow in Orthodox by Design: Judaism, Print Politics, and the ArtScroll Revolution as “the most thorough and elaborate edition of the Talmud ever produced in the English language.” The rabbi/editor had a powerful sense of the significance of the moment. He proclaimed:

Tonight we have the great honor to present the complete Schottenstein Talmud, this elucidation of the Babylonian Talmud, to the Library of Congress. This library is one of the great gifts of the United States of America. Our culture, our knowledge, our aspirations for the future, are all housed in these magnificent buildings. And now, the complete Talmud, the Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud, will take its place with Thomas Jefferson’s single Latin volume of Tractate Bava Kama.

To the Jewish historian, an event like this calls to mind and seems almost to replicate the presentation of the Septuagint, the first translation of the Bible into Greek, to Ptolemy Philadelphus’ great library in Alexandria, as it is described in the Letter of Aristeas. To some people it may even seem like a culminating moment of what Jonathan Sarna has called the American-Jewish “cult of synthesis.” But this dedication ceremony could only stir such thoughts among those who were aware of its occurrence. The great majority of American Jews are not likely to have caught wind of it or, for that matter, heard anything about the Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud itself. Although a stray ArtScroll publication may sit on their shelves, the “ArtScroll Revolution” has not changed their world at all.

Within the realm of Orthodox Jewry, on the other hand, especially its Haredi sector, ArtScroll’s traditional-minded yet simultaneously trendy publications, including the Schottenstein Talmud, have had a massive impact for over three decades. Since producing its first book of biblical commentary in 1976, Brooklyn-based ArtScroll has published many hundreds of books, ranging from translations of and commentaries on classical Jewish texts to works of adventure fiction and chick-lit (though the “chicks” are often married with children). ArtScroll’s website lists over fifty genres—Basic Judaism, Dating and Marriage, History, Reference, Spirituality, Psalms, Self-Help among them—and advertises audio books, e-books, software, videos, and the like. These publications and products are uniformly well-crafted and user-friendly. All of this has helped to turn ArtScroll into what may be the world’s largest publisher of English-language Judaica.

The admiration, however, is not universal. In the eyes of ArtScroll’s numerous critics, the publisher represents all that is wrong with contemporary Jewish fundamentalism. They accuse it of presenting a narrow-minded and dogmatic version of Judaism, selectively citing sources that are compatible only with the most closed-minded interpretations of the tradition. Its oversimplifications, ignorance of history, and at times outright distortions, they maintain, misrepresent Judaism’s complex and nuanced legacy.

Jeremy Stolow’s Orthodox by Design, the first book-length, academic effort to make sense of the “ArtScroll phenomenon,” helps us look beyond the noisy praise and blame that have been bestowed on ArtScroll’s manifold enterprises.

In an attempt to understand ArtScroll’s formula for success, Stolow asks very down-to-earth questions. Who, for one thing, makes up the market for ArtScroll books? How does the publisher attempt to reach that market? What kinds of products do these consumers want and need? Making use of his training in media and culture studies (and, unfortunately, all of the academic jargon that came with it), Stolow employs ArtScroll books as a means of examining the day-to-day lives of contemporary religious people, the books that they read, and the religious objects that they own.

He describes how ArtScroll targets a Jewish audience that hungers for greater understanding of traditional Judaism but lacks the skills and knowledge base to engage its sources directly. Responding to these people’s needs, ArtScroll has produced books and other consumer products that are wonderfully adept at combining authority with accessibility. Readers feel that they have access to an “authentic” Jewish tradition, and they get it in a user-friendly, easy-to-digest format.

However, as Stolow makes clear, ArtScroll knows that its audience is not monolithic. Some non-observant or Jewishly less-educated readers have no intention of adopting ArtScroll’s version of Orthodoxy; they merely want to learn more about their religion. But many ArtScroll books aim at ba’alei teshuvah, or potential ba’alei teshuvah, who are seeking or feeling their way to a new and different life. For many such readers, ArtScroll provides them with their first introduction to a Jewish text, holiday, or tenet. As one grateful user put it in a review of The ArtScroll Siddur on Amazon:

This is a great way to learn how to daven (pray). Before buying this siddur, I knew nothing about praying as an observant Jew. After using this book—with its detailed instructions and explanations, perfect for the newly observant—for six months I am totally comfortable with davening, knowledgeable about prayer and its basis in Torah, and I feel so much more complete in my observance.

But readers familiar with traditional texts also make frequent use of ArtScroll’s products, as a visit to just about any Orthodox school, synagogue, or home would show. Many of even the most knowledgeable Orthodox Jews prefer to get their biblical commentary or halakhic instructions from a simple, easy-to-read English book than to plow through the dense Hebrew or Aramaic prose of classical Torah literature.

ArtScroll’s “ongoing effort to present simultaneously ‘authoritative’ and ‘accessible’ Jewish books” to these diverse audiences requires it to engage in a rather delicate dance. If ArtScroll is to be authoritative, its books must display the vocabulary, language, and text-skills of experts, and need to speak in the language of the ancient tradition. But to be widely accessible, they must reach readers at whatever level of knowledge and sophistication they possess, and they must do so in a contemporary idiom. In order to describe how ArtScroll produces books that achieve both of these goals, Stolow develops the notion of what he calls “design.” He shows how all the different aspects of an ArtScroll book—from vocabulary to layout and binding—combine function and form, medium and message, to reinforce the publisher’s intentions.

The Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud serves as a prime example of this. For fifteen years, ArtScroll’s international team of Orthodox rabbis labored to produce an edition of the Talmud that would transform it from a book closed to all but the traditionally-trained into a text intelligible to anyone with even a minimal background in rabbinic Judaism (ironically, including women, whom the makers of this edition might well be happy to continue to exclude). Costing an estimated $21 million to produce and extending to seventy-three volumes, the Schottenstein Talmud seamlessly merges word-by-word translation with explanations in plain English, accompanied by clarifications of key concepts, background material, and clear diagrams and photos. To take but one example, one to which Stolow pays great attention, its rendition of Tractate Chullin 59a adds a detailed illustration of a desert locust and a side-by-side representation of a horse’s and cow’s teeth to assist in understanding the Talmudic discussion of kosher animals. But that’s only in the English translation and commentary. On the opposite page, one finds—as one does throughout the Schottenstein Talmud—the traditional-looking 19th-century “Vilna Talmud” edition of the text, which includes no such illustrations.

ArtScroll’s bestselling siddur likewise reflects its designers’ intention of both adhering to tradition and achieving a high level of user-friendliness. Its layout guides the readers’ eyes toward clear and concise directions for the precise performance of rituals, instructions that masterfully anticipate the unarticulated insecurities of the “beginner” Jew. The awkward but earnest synagogue-goer can learn a lot, for instance, from Rabbi Goldwurm’s commentary about how to recite the most basic Jewish prayer:

During the Shemoneh Esrei one’s eyes should be directed downward (Orach Chaim 95:2). His eyes should either be closed or reading from the Siddur and not looking around (Mishnah Berurah 95:5). One should not look up during the Shemoneh Esrei, but when he feels his concentration failing he should raise his eyes heavenward to renew his inspiration (Mishnah Berurah 90:8).

The simple prose of this passage appeals to the beginner. Its detailed instructions ensure that the worshipper does things just right, while the parenthetical references to classical texts of Jewish law exude traditional authority.

Among ArtScroll’s biggest moneymakers, however, are volumes much less weighty than the Talmud or the siddur, such as Susie Fishbein’s series of cookbooks, Kosher by Design (from which Stolow derives the title of his own book). These cookbooks combine short religious messages about Shabbat, Jewish holidays, or the Jewish home, with easy-to-follow instructions for making gourmet food quickly and easily in one’s own kitchen. Like a Jewish Martha Stewart, Fishbein makes classy kosher cooking look easy, but she also projects images of how Jewish women should celebrate holidays, decorate their homes, and imagine their roles as mothers and homemakers.

ArtScroll’s books, as Stolow correctly observes, from its Talmud to its cookbooks, do not simply convey the tradition; they adapt it to meet contemporary conditions. “The most rigorous defenses of tradition thus often turn out to be radical reworkings of the customary practices, received texts, and historical modes of social, political, and economic organization that are said to identify that very tradition.” Consider, for instance, the case of Rabbi Dr. Abraham J. Twerski, who has published more than thirty books with ArtScroll, including Self-Improvement? I’m Jewish! and most recently, The Sun Will Shine Again: Coping, Persevering and Winning in Troubled Economic Times. In these books Twerski is not simply preserving the centuries-old Jewish tradition of musar; he is modifying it as well. Exactly how he does so, however, is something that Stolow does not make sufficiently clear. Essentially, Twerski replaces old-style musar, which emphasizes self-restraint as the key to sanctity, with the idea of self-acceptance as the key to happiness. Out go the pietistic preaching and austere moralism, the pessimistic anthropology and the emphatic hortatory style, of so much of the classical Jewish musar literature. In comes an optimistic, encouraging, and friendly style, one that urges people to reach therapeutic equilibrium and personal happiness.

Here and elsewhere, Stolow focuses too exclusively on the extent to which ArtScroll books constitute objects and commodities and not enough on what these books actually say and the Jewish tradition of which they are part. When he does venture into the world of the Jewish canon, he is not always reliable. He is simply mistaken, for instance, when he argues that ArtScroll’s user-friendly prayerbooks represent a break with a tradition that has not put much emphasis on whether Jews understand their prayers or Torah study. Stolow attempts to back up this indefensible claim by quoting a late-20th-century popular English summary of Jewish law out of context. He goes on to misidentify this source as Rabbi Solomon Ganzfried’s 19th-century Kitzur Shulchan Arukh, which Stolow then mistakenly describes as an abridgment of Rabbi Joseph Karo’s 16th-century Shulchan Arukh. Even if we overlook such errors, the book’s discussion of Judaism as a religious and textual tradition remains far too thin.

Why spend so much energy on diagrams and photos in the Schottenstein Talmud without saying very much about the commentary itself? As someone who has been teaching Talmud to beginners for most of my adult life, I cannot help but marvel at ArtScroll’s ability to anticipate just the sort of problems such students typically face and to handle them brilliantly. How does it do this? What kinds of conceptual tools does it employ? How does it smooth over rough patches in the text? How does ArtScroll build upon the tradition of Talmudic commentary? These questions bear directly on Stolow’s key claims about how ArtScroll books make the tradition accessible, but he pays them inadequate attention.

Stolow certainly deserves credit for opening up new lines of inquiry into contemporary Orthodox Jewish life and its print culture. But his almost exclusive focus on the means by which ArtScroll publications have achieved their ends is of limited use in the absence of a serious consideration of those very ends.

Suggested Reading

Bling and Beauty: Jerusalem at the Met

In a new exhibit at the Met curators Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb wear their liberal hearts on their sleeves, imagining that Jerusalem's crowds might yet be resurrected as a convivial medieval pluralism.

“The Point of Free Will”: A Response to Abraham Socher

For mussarists, the internal struggle between good and evil is the great cosmic and spiritual drama, a position entirely in line with the conventional rabbinic view of moral decision-making.

Love in the Shadow of Death

This is a sad story, one that begins with Sarah Wildman’s discovery among the papers of her grandfather, a physician in Massachusetts, of a file of letters dating back to 1939–1942.

Books to Celebrate Israel at 70

We asked 70 leading Israeli and American thinkers to recommend the best books about Israel. Here are their top choices.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In