Scapegoats

Five years ago on Yom Kippur, my wife and I traveled with twenty community members from our home in Berlin to the city of Halle. We wanted to enliven the services of the smaller East German community, which was mostly inhabited by older Jews from the former Soviet Union. Some eighty years ago, Halle had been home to a sizable synagogue, which was destroyed on Kristallnacht. Now, we gathered in a former funeral home.

Around noon, in the middle of Torah reading, we suddenly heard bangs and popping sounds coming from outside the building. We saw on the security camera feed that a man with an automatic weapon was shooting at the synagogue walls and passersby. We heard explosions disturbingly close to where we stood. On the security camera, we saw an attacker was trying to break into the sanctuary. Yossel, who was reading the Torah, along with other quick-witted community members, immediately knew what to do. Some ran and hid in the synagogue’s back rooms, some worked to barricade entryways with tables and chairs, while others got ready to fight. I was wearing the kittel I had bought in Hassidic Williamsburg to wear under my chuppah, as I do every Yom Kippur and as I will at my funeral. At one point, I thought, Well, if I die here, at least they won’t have to change my outfit.

A few minutes later, I found myself at the top of the synagogue stairs, in front of a door leading to the back rooms in which people were hiding. I remember thinking that if the attacker broke down the door, I would throw myself on top of him and buy the others some time. The prospect of such an action so overwhelmed me that I nearly blacked out. I prayed, “Save us, God. Please, anything, save us! And if not me, then save the others! And if not the others, then save my child!”

Our attacker turned out to be a far-right gunman from East Germany, who had been inspired by other mass shootings across the world, including the mosque shootings earlier the same year in Christchurch, New Zealand. He pulled up in front of the Halle synagogue on October 9, 2019, and began shooting a homemade, 3D-printed assault rifle at the door while tossing Molotov cocktails over the outer walls of the synagogue grounds. Amazingly, the door held, and the attacker was too incompetent to scale the outer wall. After a few minutes, he shot a passerby named Jana L.; he then got into his car and drove to the Turkish kebab shop down the street, where he murdered Kevin S. (the families of both victims have requested that their surnames be kept private). The attacker’s stated goal had been to kill Jews and immigrants from the Middle East and Africa. He ended up killing two white Germans.

Instead of our planned intergenerational Yom Kippur service, we found ourselves in an intergenerational nightmare. We were Jews gathered in a synagogue in Germany, fearing for our lives as an armed Nazi banged on the doors outside. Within a few days, the public began referring to us as survivors. It was a strange label. In my childhood, survivors had numbers on their arms and thick accents. I had always thought of survivors as heroic, but I didn’t feel like a hero.

A few days after the attack, lying in my bed unable to sleep and replaying the attack in my head, I realized that the first shots were heard just as the Torah reader had chanted a verse from Leviticus about offerings and expiations: “Aaron shall offer his offering. BANG. He shall make expiation with his offering. BANG-BANG.” The passage describes how the high priest, Moses’s brother Aaron, would take two goats, sacrifice the first to God, and lead the second into the wilderness. The Torah assumes that the death of the two scapegoats was necessary to achieve forgiveness for the congregation.

I was suddenly paralyzed by a strange sort of survivor’s guilt, an irrational fear that God had let Jana L. and Kevin S. be killed instead of me, my family, and my community—as if they had died for our sins. When I stood on top of the Halle synagogue staircase and prayed for God to save us, two people had ended up dead in our place. Had God heard my prayers, accepted my request, and taken those two people as scapegoats? Had I somehow sacrificed them?

This was pure arrogance. It was also impossible. My family may have descended from the tribe of Levi, but I am certainly no high priest. And when I thought through the timeline, it was clear that Jana and Kevin had already been murdered by the time I stood on that staircase. It took some time to get everyone up the stairs and to shelter, and the miracle that the shooter was not able to enter the synagogue had nothing to do with my fervent prayers. Still, this deeply disturbing thought proved difficult to dislodge.

In the months after the attack, our time was consumed with doing our best to take care of the other members of the group whom my wife and I had brought with us to Halle. I touched base with each of them weekly. I became the point person between them and the media, the German bureaucracy, and the German Jewish community. I felt that I needed to protect them, in large part, I suppose, because I hadn’t been able to protect them in the synagogue.

That winter was the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as a lengthy court trial for the shooter. Then came Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a country where I had lived for four years. I thrust myself into relief efforts, organizing bus deliveries of medical supplies into the country and turning our Jewish Student Center in Berlin into a hostel for refugees. In short, I had no time for theological rumination, but I also knew that eventually I would have to come to terms with our experience.

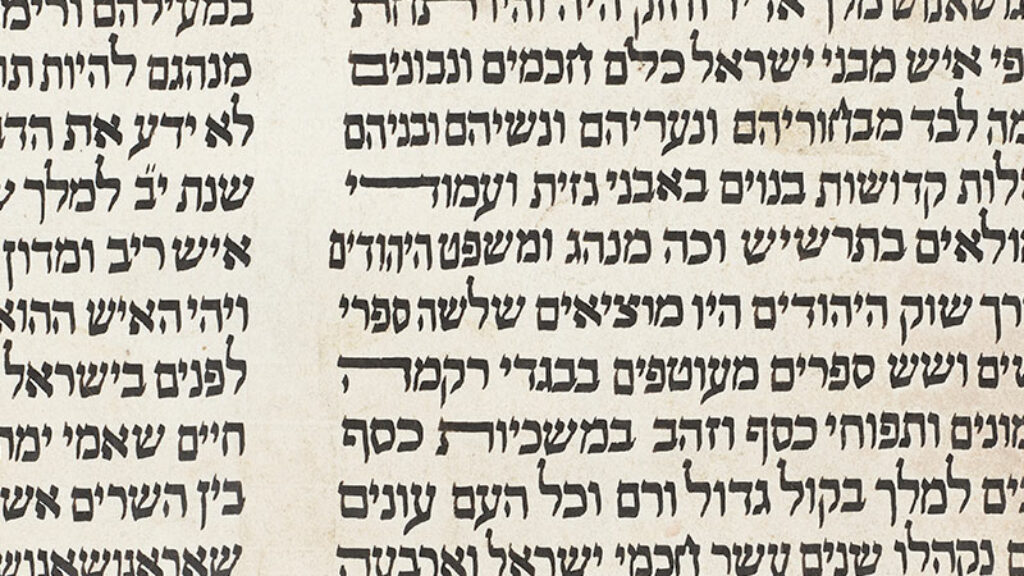

With the help of a fellowship, I decided that I wanted to focus on the meaning of the ancient Yom Kippur ritual as practiced in the temple sanctuary, the very portion that had been interrupted by the attacker. Amid the high priest’s burning of incense, slaughtering of animals, and confession of sins, I noticed a character who was usually overlooked: the ish iti, the “designated man,” literally,the “man of the moment,” who took the scapegoat from the high priest and led it into the wilderness:

And Aaron shall lay both his hands upon the head of the live goat, and confess over him all the iniquities of the children of Israel, and all their transgressions in all their sins, putting them upon the head of the goat, and shall send him away by the hand of a fit man into the wilderness. (Leviticus 16:21)

Interestingly, the Mishnah names one such individual who was chosen to lead the scapegoat bearing the people’s sins into the desert and push it over a cliff (which is how the rabbis understood the ritual):

He handed [the scapegoat] over to the one who would lead it away. All are fit to lead it away, but the high priests established a fixed [practice], and they would not allow an Israelite to lead it away. R. Yose said: it once happened that Arsela led it away, and he was an Israelite. (m. Yoma 6:3)

We know nothing of Arsela except that when it was his time to perform a task, he was there. He did not choose the scapegoat—that was done through an elaborate lottery enacted by the high priest. Nor did he confess the sins of the people on the head of the scapegoat—that was also the task of the high priest. All he did was take the animal into the wilderness, where it would meet its end. Sometimes a colorless character being in a certain place at a certain time is itself noteworthy, even if its meaning eludes us. Arsela was the “man of the moment,” a person who is remembered despite being otherwise unmemorable.

Was Arsela a survivor? Not exactly, but I can’t help but imagine the moment of his leading the goat over the cliff. A once-innocent animal now bearing the weight of the community’s sins; a harrowing moment for which he was forever remembered. Did Arsela understand the gravity of the moment? Its significance for the future Jewish community; its tragic consequences for the scapegoat? Did it weigh on him heavily? Was he ever able to embrace life for himself, his family, and his community? We will never know. Yet I suspect that even if leading the scapegoat was the hardest thing he ever did, Arsela would have seen his life’s purpose differently.

My wife’s grandmother, Olga Rosensen, is a ninety-seven-year-old survivor of Auschwitz. Just a few weeks after the Halle attack, we visited her in New York. As my wife sat in her grandmother’s living room, Olga took my wife’s hand and held it in her own, and they sat together and cried together, as Olga kept repeating, “I understand, Mammele. I understand.”

Great-Grandma Olga, as my children know her, lived through—and still vividly recalls—the true terrors of that time. She is a real survivor, having lived while so many others died. It is likely that her obituary will begin by referring to her as a survivor. Yet if you were to ask her about how she wants to be remembered, and how she sees her life’s arc, she would tell you that her children, grandchildren, and now great-grandchildren are her greatest accomplishment—living proof that Hitler did not win. Olga understands that her life means more than merely enduring the violence the Nazis and their collaborators enacted on the Jewish people. For Olga, she did not live instead of the Jewish lives that were extinguished but to bring more Jewish life into this world.

History will remember Arsela for this one traumatic moment. Should I one day merit to have an obituary written for me, “Halle survivor” will almost certainly be placed in the first line. But like Olga, I get to be the arbiter of how I see myself.

On Yom Kippur, we confront our vulnerability and our lack of control over our fate: “Who shall live and Who shall die.” We cannot fathom the difficulties we all have to endure, and we recognize that, like Arsela, we cannot dictate how we will be remembered. What we have, instead, is the possibility to define for ourselves who we want to be and pray, as the gates begin to close, that God will accept us for who we are.

Suggested Reading

Apples, Honey, and Articles

A compilation of 10 favorites from the JRB archives that follow the arc of the fall holidays, from Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, to Sukkot and Simchat Torah.

A Tale of Two Night Vigils

The tradition to stay up all night studying on Shavuot is far more well-known than the tradition to do so on Hoshana Rabbah. Neither would have been possible without Kabbalah and caffeine.

Building a Sukkah and the Call to Transcendence

David Starr says that Gordis asked the right question, but the answer may be harder than he thinks.

Empty Torah Cases and “Little Purims”

There are more than a hundred known examples of Little Purims commemorating miraculous deliverances of Jewish communities in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In