A Tale of Two Night Vigils

Although the so-called tikkun observed by many Jews on the first night of Shavuot is by far the best known today of the various all-night vigils that have emerged since the 16th century, it was long paired with a now almost-forgotten nocturnal study session observed on the night before Hoshana Rabbah, the seventh (and final) day of Sukkot. Samuel Spiro, who was born in 1885 in the Hessian village of Schenklengsfeld, described his “vivid memories” of accompanying his father, the community’s rabbi, to the various study sessions on those nights. Although the community numbered no more than 50 families, its adult males were divided into chevrot, or pious societies, and each society met in the home of one of its members. As Spiro wrote in his 1948 memoir:

The tables were festively set and covered with all sorts of fruits and baked goods. At midnight there was coffee and cake . . . Every family in whose house the learning took place sought to offer its best in the way of food and drink, and on the next day their hospitality was compared in the synagogue courtyard.

That coffee was served was hardly coincidental. As I showed in a 1989 article, both these study vigils began to spread through the Ottoman Empire during the 16th century, the same century in which coffee (kahwa in Arabic) first arrived, changing the possibilities, both sacred and profane, of nightlife in such cities as Cairo, Damascus, and even Safed. (I had come to the subject after reading the formidable French historian Fernand Braudel on coffee’s spread and cultural influence; when my first public lecture on Shavuot and coffee was announced, a colleague unfamiliar with Braudel’s work asked if it was a joke.)

A revealing picture of the sort of learning undertaken at these vigils emerges from the 18th-century statutes of a Jewish burial society (chevra kadisha) in Worms, in Germany’s Rhineland, which was evidently the first pious society to require its members to attend both the Shavuot and Hoshana Rabbah rites. The society’s 1723 rules required its members to study either Mishnah, with the (relatively undemanding) commentary of Obadiah of Bertinoro for half an hour each day, or something simpler for those who found this material too difficult. This suggests that the society’s all-night study sessions were not particularly demanding. Members probably recited from the standard printed liturgy, which had first appeared in Venice in 1648. Those who failed to attend were fined a quarter of a gold florin, though they were exempted from the fine if they belonged to another charitable society that met on those nights.

No mention was made in the 1723 statutes of studying the entire night or of refreshments that might fuel such study. One might think that the Jews of Worms had not yet heard of tea or coffee, which were still new to Europe, or had not yet learned of their efficacy as stimulants. As we shall see, however, both beverages appear in the burial society’s statutes of 1731, though in a perhaps surprising connection.

The first documented instance of a tikkun vigil, more or less as we now know it, took place in the early 16th century. In a well-known letter, the kabbalist Solomon Alkabetz, now mostly remembered as the author of Lekha Dodi, recounts the mind-bending experience of spending Shavuot night with the great halakhist Joseph Karo. Both men were later to become key figures in the kabbalistic circles of Safed, but Karo was then living in Nicopolis, in present-day Bulgaria, where his father had preceded him as chief rabbi. Although the Zohar, the major work of medieval Kabbalah, had not yet been published, Karo was strongly influenced by its teachings, as the great historian Jacob Katz deftly demonstrated. Karo must, therefore, have been familiar with the passage in the Zohar that describes its mystical hero Rabbi Simeon bar Yochai engaged in Torah study “all night when the bride was about to be united with her husband.” As the scholar Isaiah Tishby explained, this referred to the night of Shavuot, when the Shekhina, which is the tenth sephira (a divine emanation, power, or rung), often symbolized as a bride, was to be united with the higher sephira of Tiferet, her husband. Rabbi Simeon explained to his disciples that those studying Torah on the night of Shavuot, proceeding from biblical texts to rabbinic and mystical ones, were like friends of the bride staying up with her on the eve of her wedding, adorning her with ornaments so that the groom would find her attractive. When the groom saw his beautifully adorned bride at the ceremony, accompanied by her bridesmaids (the Torah scholars), he would inquire after them and bless them.

In Nicopolis, sometime in the 1530s, Rabbis Alkabetz and Karo decided to reenact that allegedly ancient Zoharic scene. Karo, the senior of the two, asked Alkabetz to prepare an order of study—or rather, recitation—for the occasion. The order of texts followed by the two scholars seems to have been improvised and was somewhat haphazard, a characteristic sign of a tradition being “invented.” They read the opening passages of Genesis, then two from Exodus that recounted the giving of the Torah at Sinai, but skipped Leviticus and Numbers on the way to Deuteronomy, from which they recited both an early passage and the book’s final chapter on the death of Moses, which also concluded the Pentateuch. From the Prophets they read only the two passages that served as haftarot on each of the two days of Shavuot—from Ezekiel and Habakkuk. Alkabetz’s choices from “the Writings” were even more erratic: some psalms followed by the books of Ruth and Song of Songs in their entirety, and then “the final verses of Chronicles,” which conclude the Hebrew Bible.

According to Alkabetz, when they turned from Bible to Mishnah, a heavenly voice interrupted, speaking through Karo, who was then presumably in a trance. The voice identified itself alternately as the Shekhina and as the personification of the Mishnah itself, and congratulated the two scholars for having “resolved to adorn Me on this night.” That was the soft voice of the Shekhina, but then, according to Alkabetz, the Mishnah appeared, speaking more shrilly as a difficult-to-please Jewish mother:

I am the Mishnah, the mother who chastises her children and I have come to converse with you. Had you been ten in number you would have ascended even higher, but you have reached a great height nevertheless.

Ten men is, of course, a minyan, and what the personified Mishnah was probably pointing out is that a minyan is required to recite the seven benedictions at a wedding, in this case between the sephirot Shekhina and Tiferet.

There is no evidence of Karo and Alkabetz having performed a similar rite on Hoshana Rabbah, but by the late 16th-century scholars in Safed were staying up on that night too reciting “psalms and penitential prayers,” as reported by their colleague Abraham Galante. Galante described the eve of Shavuot as a night in which “every congregation assembles in its own synagogue and those present do not sleep the whole night long.”

Just as Shavuot had been transformed in rabbinic times from a Temple-oriented summer harvest festival to one in which the giving of the Torah was celebrated, so too had Hoshana Rabbah been transformed from the festive march of willow branches to the day of repentance and final judgement, at least for those who felt that they needed a post–Yom Kippur extension. In that spirit, the custom emerged, in medieval Spain, of examining one’s shadow on the night of Hoshana Rabbah to discern one’s fate during the coming year. Having no shadow meant that one would die; the absence of various limbs from the shadow meant that family members would die. It is understandable, then, that the Hoshana Rabbah tikkun, as observed in Safed, included penitential prayers.

Even earlier than the custom of examining one’s shadow on Hoshana Rabbah, a custom emerged of staying up all night to read through the entire Pentateuch, from Genesis through Deuteronomy, to make sure that one had finished the Torah before Simchat Torah commenced on the next day. The custom is first mentioned by the 13th-century Italian scholar Zedekiah Anav in his Shibbolei ha-Leket. From Italy the custom spread to Spain, where it is first mentioned in the 14th century, but this was not yet the mystical night vigil as magical tikkun.

In contrast to their rapid reception in Ottoman Jewish communities after the Spanish Expulsion, the Shavuot and the Hoshana Rabbah vigils spread more slowly to the Jewish communities of northern Europe, where coffee arrived considerably later as well. This can be seen in the comments of Isaiah Horowitz, whose book Shne Luchot ha-Brit was completed in Jerusalem during the 1620s and published posthumously in Amsterdam in 1648–1649. Horowitz, who had served as a rabbi both in Frankfurt and his native Prague, had clearly not encountered the Shavuot vigil in either of those cities, for he described it in his wide-ranging work only as having “spread throughout the land of Israel and the [Ottoman] Empire.” The Hoshana Rabbah rite was described there similarly as “practiced in the land of Israel, like the night of Shavuot,” but including both study and prayer. Although Horowitz, who stressed that it was best to perform these rites with a minyan, had not encountered either vigil in his native northern Europe, his enormously influential work—the fourth edition of which was published in Frankfurt in 1717, after having already appeared in several abridged editions—was instrumental in their spread from the elite circles of Safed kabbalists to the ordinary Jews of the Worms burial society.

Although the Worms statutes of 1723 had made no mention of coffee or tea, four decades later things had changed dramatically. By 1763 the member who hosted the study sessions was required to provide “two measures of old wine,” but coffee would be paid for by the society itself. Wine, in fact, had long played a central role in the society’s (non-burial) activities, as one might expect in the Rhineland. The inaugural statutes of 1716 stipulated that at the biannual officers meeting no more than two measures of wine were to be consumed. Those of 1731 stated that at the annual banquet only wine and brandy could be served at the society’s expense, although members could bring their own beer. Coffee and tea with sugar, however, were explicitly and strictly banned as contrary to the banquet spirit and were as strenuously forbidden as if, the statutes read, they were “heathen wine.”

By 1763, however, the status of coffee had clearly changed among Rhineland Jews. It was no longer seen as interfering with the spirit of pious festivity aimed for on the occasion of the annual banquet. Two and a half centuries before college students and clubbers began mixing vodka with Red Bull, the burial society stipulated that henceforth at its annual banquet “only wine, brandy, and coffee” could be served at the society’s expense. In 1763 the society decided that both coffee and wine would be served at the study sessions on Shavuot and Hoshana Rabbah. Brandy, it may be added, was also permissible, but was not necessarily provided either by the host (like wine) or the society (like coffee).

Late in the 18th century the statutes of London’s Chebra Rodphea Sholom, or Pursuers of Peace, required its rabbi not only “to expound on every Sabbath day” concerning that week’s “portion of the Law or the Prophets,” but also to attend their study sessions “on the First Night of Pentecost and Hoshana Rabbah . . . for which he shall be allowed Five Shillings each time,” but only “on condition that he attends the full time of the meeting.”

Although there is no reason to believe that the great London Jewish philanthropist Moses Montefiore ever became a member of Rodphea Sholom, he did come to care a great deal about the Hoshana Rabbah vigil. Montefiore’s secretary Louis Loewe, who accompanied him on his 1840 trip on behalf of the Jews imprisoned in Damascus as a consequence of an infamous blood libel, reported in his diary that they arrived in Constantinople (now Istanbul) just before Yom Kippur. Montefiore and his entourage, which included his wife, Judith, were staying at the home of the noted philanthropist Abraham de Camondo. In the Ottoman capital at the same time were several Eastern European rabbis, among them Samuel Salant, later to become chief rabbi of Jerusalem, on their way to the land of Israel.

In his memoirs, the Jerusalem educator Ephraim Cohen-Reiss wrote that Montefiore and Salant, who were later to become friends, first met when Montefiore requested of Camondo that he invite Salant and his colleagues for the first night of Shavuot, so that a proper tikkun could be recited with a minyan. Late that evening, according to Cohen-Reiss, Montefiore, who was more than three decades older than Salant, began dropping off to sleep, but was reluctant to go to bed and miss the great mitzvah of staying up all night. The European rabbis asked Salant to intervene, at which point he told Montefiore that he himself would be sleeping had the visiting Englishman not organized the tikkun. Having done so, Montefiore had already garnered the reward for the rite being performed in the presence of 10, and could thus go to sleep. From then on, Salant had supposedly told Cohen-Reiss, “we were close friends.”

It is indeed true that Montefiore and the future chief rabbi met in Constantinople and that they became good friends, but they did not recite the Tikkun Leil Shavuot liturgy together in 1840. They did, however, perform the parallel rite for Hoshana Rabbah, from which Montefiore (and Judith) retired early. As Loewe wrote in his diary:

About ten o’clock the [local] gentlemen came to read prayers with us all night, in consequence of Hoshana Rabbah. We invited the Hakham, Rabbi Jacob Dayan . . . We have also the gentlemen who were to proceed to the Holy Land. We passed the night very comfortably Sir M. and Lady Montefiore staying with us till 3 o’clock.

Rabbi Salant must have confused the nights of Shavuot and Hoshana Rabbah in his memory, especially since he told Cohen-Reiss the story several decades after it took place. Whether or not he truly told Montefiore that he himself would have been in bed had not the latter organized a tikkun is less certain. Readers who find themselves in the future nodding off on either of those nights are welcome to recall whichever version of the story suits them. They might also try another cup of coffee.

Suggested Reading

Strange Journey: A Response to Shmuel Trigano

Two historians challenge Shmuel Trigano’s analysis of anti-Semitic violence in France.

An Israelite with Egyptian Principles

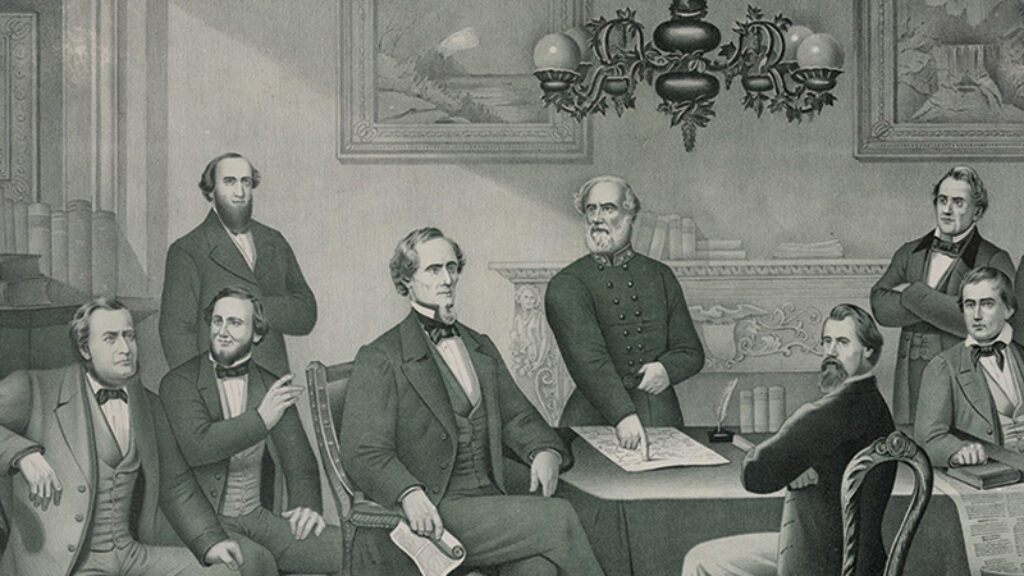

Judah Benjamin was a brilliant New Orleans lawyer who became the most important cabinet member in Jefferson Davis’s Confederate government. He was, Senator Benjamin Wade correctly declared, one of the “Israelites with Egyptian principles.”

Purity and Obscurity

When contemporary Jews of priestly lineage avoid cemeteries, when ordinary Jews wash their hands before eating, or immerse themselves in ritual baths, they are acting according to the dictates of an ancient system.

Faith in Doubt

Can doubt provide the space that allows secular and religious Jews to coexist in Israel?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In