Look Ma, No Hands!

Memoir is risky business. Its reputation? Slightly dubious. Its vices? Vanity, indiscretion, omission. Don’t trust it, said Orwell, unless it reveals something shameful. Even then, you might wonder why someone probes their past, poking around in the attic of their psyche. Why not let demons rest?

If anyone understands these hazards, it’s Joseph Epstein, a great practitioner and skeptic of personal writing. “We know all autobiographies are public lies,” he once wrote. Elsewhere, he called memoir self-gossip—“with roughly the same degree of truthfulness.” Memoirs are “cover-ups,” he wrote, and “delightfully clever deceptions.” Write one? He swore he wouldn’t.

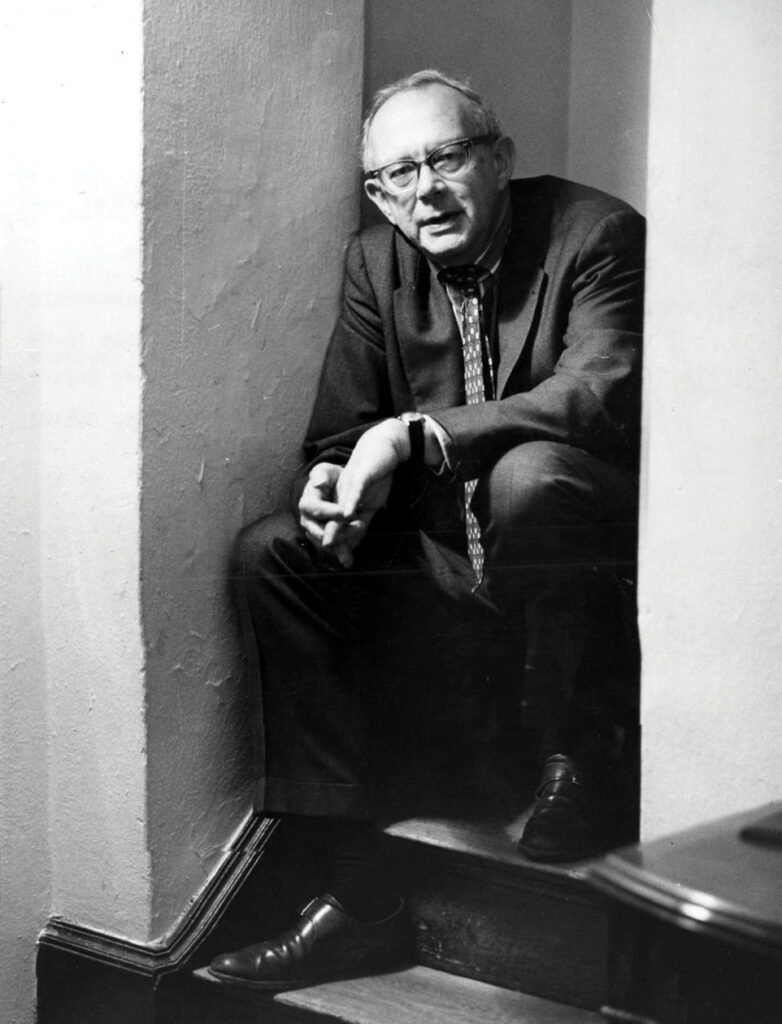

A few years ago, Epstein changed his mind. The result is Never Say You’ve Had a Lucky Life, which does little self-gossiping and barely breaks a sweat. A charming publicity photo shows the gray-haired author on a unicycle, face calm, pants pressed, shirt tucked in. He is without his signature bowtie, but the message is clear—as clear as Epstein’s crystalline prose. This is a man who keeps his balance. It also whispers a warning: Charm offensive ahead.

Charm, of a highly cultivated sort, is Epstein’s trademark, and, fittingly, he’s had a charmed career as a writer and editor, a career hardly possible today. Epstein began in 1959, a golden era for intellectual magazines, when freelancers could choose between Dissent, Commentary, and The New Republic. Epstein chose all three. He then revived The American Scholar—a fusty journal that, by his own admission, had bored the heck out of him.

Across sixty years, his singular mission has been to combine humor and high seriousness for the common reader. Epstein has the gift of enlivening everything he touches. (“Writing about nothing at all, he would doubtless still seem mordantly witty and gracefully articulate,” wrote Christopher Lehmann-Haupt). He is beyond prolific—at latest count, he’s written thirty-one books, a number that may have risen by the time you finish reading this. He has a reasonable claim to being the hardest working literary critic of the last sixty years.

He is also the author of a reliably charming persona. In the personal essays now collected in Familiarity Breeds Content and throughout his career, he has portrayed a witty, cultivated fellow, sometimes cranky, who can rattle off all the ways he isn’t cool. He pictures hell as a place where he’s forced to wear denim. He was a young fogey in the ’60s, perfectly unhip. While others dropped acid, he reviewed Lillian Hellman’s memoirs. The closest he got to getting stoned was reading Tom Wolfe’s tales of psychedelics.

In Never Say You’ve Had A Lucky Life, Epstein deploys the gallant false modesty common to memoirists. Indeed, he’s full of charming disclaimers. His life is boring. He’s married to routine. He couldn’t possibly have secrets, and if he did, you wouldn’t care to know them. The message is clear: Don’t expect daring, Byronic adventures. This was a quiet, deskbound life. Epstein calls it “spectatorial.”

In a sense, he’s right. Epstein amassed no fortunes and cured no diseases, and nothing of his early life foretold greatness. Myron Joseph Epstein was born in 1937, in Chicago, into a stable, middle-class Jewish family. Home was a calm, civilized place, if somewhat chilly and formal, even on birthdays. Epstein’s father, a jewelry salesman, was a decent, courtly man whose religion was work. His mother, a tough, elegant woman, was a puzzle to her son, as inscrutable as she was formidable.

Epstein insists he loved his parents, and on some essential level he must have, yet his portrait exudes ambivalence. On one hand, he won “the parent lottery”: terrific freedom, little supervision, but also an utter lack of affection or praise. Epstein’s mother—“an excellent ego deflater”—supplied the sort of experiences one shares with a therapist later in life. A few droll examples:

Epstein, now an adult, joins the Northwestern English department. “That’s nice,” says the mother, “a job in the neighborhood.”

Epstein wins a Chicago Tribune writing award. “We get that junk in the mail all the time,” says the mother. “I just throw it out.”

While speaking to his mother on the phone, Epstein hears typing in the background. “Why not?” she shrugs. “I don’t need all my attention to carry on a conversation with you.”

A snapshot of such a family appears in Epstein’s story “Kaplan’s Big Deal”: three private people who never discuss feelings or problems. From these tough, laconic adults, Kaplan learns four lessons: “Stand on your own two feet, work out your own problems, don’t leave a mess, be a man.”

Lonely as a child, life improved once the Epsteins moved to West Rogers Park. “High school was paradise,” he writes, and perhaps it was. For many, it’s an ordeal of hormones, social sifting, and a big decision: to blend in or stand out. Epstein blended in. “It was many friends I wanted: multitudes, large assemblages, whole hordes.” Neglected at home, he won popularity with an affable “good guy” persona. Writing is seduction, and Epstein’s charm was already obvious.

Indeed, it was useful. In Epstein’s telling, he lived in two worlds: his quiet, orderly home and seedy, pulsing Chicago, full of schemers and shtarkers, wise guys and hustlers. Among these louche characters, “Mike” (as he called himself) was like Augie March, tugged toward mischief. By senior year he was gambling and visiting prostitutes (he drew the line at watching a friend have sex; that would have been “to demean myself”).

After high school, Epstein drifted from state school to the University of Chicago. Here the

“genial screw-off,” who still looked like a high school freshman, made a major change. By day, he studied. At night, he read: Capote, Salinger, Arthur Miller. He discovered Commentary, an argument in the shape of a magazine, and Partisan Review. He was riveted. “Maybe,” he thought, “with diligence, one could someday write for these magazines.”

It was a time of strenuous self-formation. He sought elevation, refinement, cultivation—the Jamesian ideal. During a tour in the peacetime army (“I must have been the only soldier who went off on bivouac with copies of Partisan Review and Dissent in his backpack”), he struck out as a writer. Mike became “Joseph” professionally. He began pronouncing his last name Ep-stine (“it sounded more frankly Jewish”) instead of Ep-steen.

He read purposefully: to learn craft and technique. “I had crossed the line,” he would recall, “and become a member of what I think of as the ‘bookish class.’” Imitation became transformation.

Epstein’s story can seem almost archetypal. Over a few years, talent became passion; passion became obsession; obsession became vocation. It’s also a familiar Jewish story. Many postwar Jewish writers (Roth, Ozick, Herbert Gold) apprenticed to James, adopting Jamesian notions of high culture. “As in a religious conversion,” Epstein would write, “all one’s former values toppled, all one’s past suddenly seemed profane.”

Epstein’s boyhood friends were bemused. Mike didn’t sound like Mike anymore. He sounded like Lord Palmerston. “Where did that come from?” Epstein would wonder, hearing himself talk. Epstein’s affectations (“Next he’ll be carrying a walking stick,” a friend once joked) served a purpose. The child who “excelled nowhere” had found distinction. As Epstein recalled, “Elegance for me was available only within the frame of prose.”

At first, publication was thrilling—and addictive. “Hot damn!” he thought, toasting his first byline in the anti-Communist New Leader. Never mind the terrible pay (zero). He was going places, his name appearing next to Bertrand Russell’s. That was payment enough.

Epstein’s writing improved rapidly. He had an easy, confident style, casual yet precise, and frequently witty. He had arrived with perfect timing: Norman Podhoretz had turned Commentary from a staid anti-Communist monthly into a lively liberal colloquy. (“The most interesting magazine in America,” Victor Navasky said at the time.) And Irving Howe was running Dissent, which, though socialist, rejected strident leftism. Epstein fit in there too.

His politics were liberal, even radical, but as a reviewer, he might have fit in anywhere. He aimed to be neither crass nor dull—neither a boor nor a bore. Young Epstein was, of all things, an enthusiast, prone to gushing. “It is always sweetest to appreciate,” he told a friend, noting the critic’s duty “to call attention to something you care about.”

Appreciate he did. Reviewing Leon Edel, the illustrious biographer, Epstein hailed his “refinement, subtlety, wide learning and great good sense.” Another favorite, A. J. Liebling, showed how to be “urbane without cuteness, skeptical without sourness, and witty in a way that was at bottom serious.” The reviews Epstein tapped out on his Royal Standard typewriter seemed effortlessly confident. Behind the scenes, he was always cramming, filling gaps in his knowledge. He began seeing his job as “getting one’s education in public.”

Epstein was a bundle of vanity and strong, unfocused ambition. Should he write books? Fiction? Reviews? He suffered from “every sort of unsatisfied literary desire,” he told the art critic Hilton Kramer in a letter. Reading the masters, he found himself lacking. “I may very well be one of those pathetic types whose ambition is four or five times greater than his talent.” He had charm and decent judgment—but how to employ them? “You see, the bitch is, I’ve got to be writing something. I may really be running out of possibilities.”

The late 60s were especially anxious. “Drugs scare the hell out of me,” he told his journal. He suffered from “fear of living,” which included travel. Yet he was determined to succeed on his own terms—as an intellectual. That meant protecting his time and, critically, his integrity. No moral compromise. Radical independence.

Around this time, a final act of self-creation took place. “Enough discontent,” he wrote in his journal, “and a little more civilization, please.” From then on, however gloomy or annoyed, he would project good humor. Writers like Mencken, darkly amused, and Waugh, smiling into the void, were role models. They were victims—who isn’t?—but never complained. They met darkness with humor, sadness with mirth. They cultivated an amused detachment.

Luck is Epstein’s keynote, and he was lucky indeed. In the early 70s, Irving Howe, the Dissent editor, arranged a job interview for him at Northwestern. Behind the scenes, his friend Gerald Graff courted the English department and quietly enlisted Saul Bellow. “Naturally, all this will remain confidential,” he wrote Bellow, who vouched for Epstein’s erudition and good sense. It took a village, but Epstein got the job.

Success begat success. Soon Epstein was editing The American Scholar. (“His integrity is beyond question,” Hilton Kramer attested.) Epstein also helped his own cause—that is, he made his own luck. During his job interview, he was asked what he would do about younger readers. Let them grow up, he said. The job was his.

As an editor, Epstein didn’t court readers. Mainly, he assigned articles he wanted to read, and, in effect, let thirty thousand people read over his shoulder. Editing requires diplomacy, which he had, and moral compromise, which he didn’t, but he assumed his role confidently. He wrote exceedingly generous rejection letters. And, of course, he charmed. To one dilatory writer, he threatened “heavy dunning,” to be followed by “very late night telephone calls, rocks through your parlour window, and worse.” Mischievously, he assigned himself essays. He wrote as “Aristides,” an ancient Athenian general who was called “the just.”

Aristides had fun. He could riff, ramble, reminisce. (The essay—the most free and capacious literary form—suited Epstein nicely.) Until then, Epstein wrote stylishly and affably, without much bite. Rather rapidly, that changed. The ’70s were Epstein’s ’60s, when he got free and loose. He vented many annoyances (“A full list of his dislikes would read like a small-town telephone directory,” a scholar observed). Critics, like novelists, have their obsessions, and Epstein’s was dignity. So much culture was undignified. Pornography. Vulgar slang. Shaggy beards. Slovenly clothing.

“Does the cheerful snob that I advertise myself as being begin to seem the beady-eyed fanatic?” he wondered. If so—well, so be it. “I am—as a great many people will tell you—no longer a Good Guy,” he wrote. “I may not even be . . . a nice fellow.”

Being not nice, even cruel, is a writer’s birthright, and Epstein seized it. “Who can bring himself to care about the subject of camp?” he wrote in 1973. “Ken Kesey’s bus load of junkies? Or the Jewish American Princess?” For those counting scalps, that’s four: Susan Sontag, Ken Kesey, Tom Wolfe, and Philip Roth.

What, exactly, was going on? Epstein’s politics were shifting rightward (he abandoned Dissent in 1974). The affable litterateur had turned prickly contrarian. In his 1975 book on divorce, Epstein composed a neat little ode to self-liberation:

If nothing lasts, then you might as well grab what you want, plunge your arms in up to the elbows, let no one or nothing stand in the way of your getting your own. With no one to account to, all is permitted.

Fifteen years earlier, during his army stint, Epstein met a charming, flirtatious waitress named Elizabeth in a Little Rock bar. A year older, a divorcée, she had lost custody of her two children. After four or five dates, she appeared at Epstein’s door with a suitcase. Before long, she was pregnant. Their next date was at city hall.

Epstein doesn’t say whether he was in love with Elizabeth, only that her hard-luck background compelled him. The couple married but gradually grew apart, then embittered. Divorced in America begins with a bang: a confused, anguished Epstein in divorce court. It’s a scene out of Dante. He is standing “in a puddle”—presumably sweat, although blood and tears come to mind. Epstein recalls “an emotional ravaging.”

Divorce, he wrote, produced “floods of bitterness, storms of hatred.” It also changed him. From then on, he wrote freely and unashamedly. He chronicled his vices, from snobbery to pedantry to expensive bowties (“I am not a rich man—only a vain one”). Like all writers, he needed praise—“great, heaping, banana-split dishes of it.” Epstein’s vice trilogy—Snobbery (2002), Envy (2003), and Gossip (2011)—mixed confession with rumination and social history.

Epstein’s boldest confession, which shadowed his career ever after, appeared in 1970. It was the year after Stonewall: gay pride was stirring; gay rights were loudly demanded. What Epstein saw was decadence and stridency—the 60s in microcosm. He was then raising four children on his own: his ex-wife’s children and their own two boys.

Epstein’s essay, “Homo/Hetero,” ran in Harper’s Magazine and went 1970s viral, sparking noisy protests (a dozen activists, trailed by a television crew, stormed the Harper’s office). It was read as an attack, a homophobic snarl. Was it? “My ignorance makes me frightened,” he wrote, admitting that “wholly selfishly, I find myself completely incapable of coming to terms with it.” It wasn’t polite, it wasn’t enlightened, but it was what he felt.

“It ought to cause me a lot of trouble,” Epstein had predicted. To this day, “Homo/Hetero” draws condemnation, though it expresses both sympathy and disgust as well as confusion. “My only hope now,” Epstein later wrote, “is that, on my gravestone, the words Noted Homophobe aren’t carved.”

Epstein continued to write freely through the 1970s. In 1982, he imagined a court that “metes out literary punishment.” That court was already in session, Joseph Epstein presiding. “Who, you might ask, appointed me sheriff?” he wrote. To Epstein, that was a critic’s job: enforcing standards, defending distinctions. Critics were sentries. They protected literature, harnessing “a controlled anger aroused by breaches in literary justice.”

Epstein—now well known and widely published—had several platforms. There was Commentary, where a gifted editor, Neal Kozodoy, sculpted his essays (sometimes a bit too aggressively for Epstein’s taste), and, starting in 1982, The New Criterion, edited by Hilton Kramer.

Epstein was never livelier or more contrarian. He dismissed One Hundred Years of Solitude (“eighteen to fifty-one years of solitude was sufficient”). He read Mailer in a stupor—“my eyeballs glazed like a franchise doughnut.” They got off easy compared to John Updike (“Look Ma, no thoughts”) and Renata Adler (“We are, you might say, off and limping”). In the 1970s, Epstein had vowed to review only “books that I really love or really hate.” He kept that promise to himself in the 80s.

It wasn’t only acerbity he flaunted. “Is it permitted to complain about sex in novels as late as 1983?” he asked. Try and stop him. Epstein quivered, and not with pleasure, at R-rated “bonking” and “shtupping.” Mess and overflow may be our lot, but Epstein objected. “It would be better literary manners not to mention sex at all,” he wrote.

In more cheerful moments, his pen roamed playfully over smaller subjects: the joy of juggling, the dignity of cats, having hair that resembled astroturf. He took stock of his good fortune: “a wife I adore, work that keeps me perpetually interested, good friends, good health, and (thus far along) supreme good luck.” After his divorce, Epstein married successfully, to Barbara Maher, “the least vulgar person I have ever known.” “Being chosen for her partner elevated me in my own eyes,” he wrote. They married after Epstein’s stepsons left for college.

Maher wasn’t Jewish, not that Epstein much cared. He wasn’t religious, and Jewish matters could seem peripheral to him. Yet he had been raised Jewish and joined Jewish cliques in high school. (“Jews on one side, Gentiles on the other,” he recalled. “This, we assumed, was the way of the world.”) Epstein’s Jewishness deepened over the years, a mixture of culture, kinship, and Jewish pride. “As for my Jewishness . . . I find it is a central strain in my character and even exult in it,” he later wrote.

A deepening engagement with Jewish writing was also apparent. He reviewed Roth thoughtfully, if acidly. He favored Cynthia Ozick’s essays over her fiction, disliking her flights of fantasy. (“Madam, what is that living room doing on the ceiling? Madam, I implore you, get those Jews down, please!”) While praising Malamud’s sensitive early stories, he ruefully dismissed the later novels. A 1982 essay, “Malamud in Decline,” began by asking, “When do we give up on a novelist?”

But he could still come in praise. “I cherish the books of Isaac Bashevis Singer for their Jewish spirit,” he wrote, likening him to Tolstoy: “a man of dignity, humility, the broadest intelligence and extraordinary dedication to the act of writing.” Epstein’s father’s family, from Białystok, was little known to him, and this “Jewish historical blackout” troubled him. He credited Singer for “helping to put me in touch with my almost entirely lost historical past.” He even forgave Singer’s sex obsession. In Singer’s fiction, he said, “the pleasures of sex mix with the terrors of guilt and sin, and somewhere off in the distance you feel perhaps God is watching.”

It may be the fate of personal essayists—even “lucky” ones—to chronicle their difficult, luckless periods. Such was Epstein’s burden in the 1990s.

Epstein’s politics—he had supported Reagan and loved politically incorrect jokes—had alienated The American Scholar’s editorial board. There was no savior, certainly not Bellow, now an ex-friend. The relationship had always been fraught: Bellow expected obeisance, and Epstein surely resented Bellow’s power over him. Wounded, Epstein wrote two fictional revenge stories (“Eli seemed to betray everyone who ever loved him”). Such revenge was “the closest to power that writers are permitted to feel,” Epstein later wrote. At the same time, “It tends to leave a stain that doesn’t quite ever wash out.”

Aging brought additional tzuris. In 1997 Epstein turned sixty. After a health scare, he braced for disaster: “heart attack, cancer, plane crash, car accident, falling object, choking on food, murder.” His sense of worry was vindicated. In his memoir, Epstein breezes past his triple bypass surgery. (“I went into it with surprising sangfroid and came out well.”) In truth, he was terrified. He likened surgery to “having to face a vicious bully, who is going to beat the hell out of me.” He recovered fully, yet with “an abiding vulnerability I hadn’t felt before.”

The great tragedy of his life, his son Burton’s death by drug overdose, left him shattered. About his grief, he says little, and who can blame him. Not everything is material. Epstein writes that he thinks of his son often and still wears the wristwatch he gave him. “I incorporate his name into my various computer passwords,” he wrote recently. Such details have an awful pathos, no gilding required.

What do readers want from memoirs? Charm, good company, some “self-gossip,” not too much. By these measures, Epstein succeeds. Philip Roth once described a type of book that “won’t leave you alone. Won’t let up. Gets too close.” Epstein is the opposite: a civilized host. He invites you in, shares some stories, refills your tea, and politely shows you the door.

What he doesn’t do is overshare. As he often insists, he abhors confession, even with friends. At some point, it’s clear, Epstein built a moat around himself. “Joe Epstein I like and respect,” Bellow once wrote, “but I don’t open my heart to him because he doesn’t have the impulse . . . to open up.” Nothing personal. Epstein treats readers similarly. Instead of confession, there’s charm, drawing you in while keeping you at a distance.

And yet, in rare moments, something deeper emerges. “My heart leapt, I nearly wept,” he once wrote of a cherished friend’s wedding. Such moments, when feeling overwhelms reticence, are rare and powerful. Epstein could write tenderly about close friends, including his “ideal older brother,” Hilton Kramer.

Closest of all, perhaps, was Edward Shils, his model of refined cosmopolitanism. In person, they respected boundaries. (“We do not talk of things of the heart,” Shils said.) Yet after Shils’s death in 1995, Epstein wrote a requiem, “My Friend Edward,” and a poem, “Edward Shils in Heaven,” that addressed its subject directly: “Dear Edward, sleepless, lonely, I think of you tonight.” This wasn’t Sheriff Epstein or the manly stoic. “Sweet curmudgeon,” he wrote, “do you ever think of me?”

Finally, there is Epstein’s granddaughter, Annabelle, the product Burton’s love affair with an African American woman. Initially, Epstein ignored the girl (“The world didn’t need more children born out of wedlock”). His stubborn resistance melted. When the pair finally met, he was utterly smitten, and the winsome, intelligent girl became his favorite.

Years later, Epstein cracked a femur, and the girl (then grown and married) rushed to his side. “For that month my granddaughter became, in effect, my mother,” Epstein wrote. During that time, “I felt the full benevolent force of family, and a fine feeling it was.”

Someone who writes of feeling mothered, of finally experiencing family love in his eighties, isn’t being guarded, as one New York Times critic complained. Nor is Epstein airbrushing his darker side when he describes initially cold-shouldering his infant granddaughter.

In one area, however, I did wish for greater candor. Writing is mostly failure. It’s hard work that looks a lot like idleness and requires constant defending. I would have loved to hear Epstein’s candid thoughts on the writing life, particularly freelancing, which can feel like being a perpetual son, always anxious before authority. And what of editors, those secret collaborators and maddening meddlers?

But that’s not this book. Instead, we have a small, modest memoir, neither capstone nor footnote, which sometimes recycles old essays from Commentary. The stakes are mostly low; life’s errors and confusions are largely elided. And Epstein’s “fine invigorating hatred” (his phrase) is mostly missing. It sometimes feels inert compared to his livelier oppositional writing.

That version of Epstein still flourishes. If age has softened him or broadened his sympathies, I haven’t noticed. “I don’t think of myself as very political,” he wrote in 2013. He was, rather, “a small older gent . . . calling out, fairly frequently, bullshit, bullshit, bullshit.” Over the years, he found as many words for bullsh it as the Inuit supposedly have for snow. Of course, bullshit is in the eye of the beholder, and Epstein leans conservative. He dislikes DEI (“Didn’t Earn It”) and progressive activism (“feminism-racialism-gaiety-radicalism”). In 2013, he compared Gore Vidal to “a car with a dead engine whose horn nevertheless keeps sounding off.”

In 2020, to top himself, he called Jill Biden “kiddo” in the Wall Street Journal. Outrage. Calumny. “I do seem to have this need to create a scandal,” Epstein wrote in 1970. He still did. Epstein didn’t think that Biden’s doctorate in education should make her “Dr. Biden,” but the ensuing tempest was over more than doctors without stethoscopes. It was over gender and the right to offend. Epstein survived his auto-da-fé, but Northwestern disowned him. Publicly, Epstein laughed. He was eighty-three, he said. Too old to care.

For all his transformations, Epstein’s writing is recognizable across the decades. A 1961 article opens, “A philosopher of my acquaintance makes two simple demands of a city.” Sixty-three years later, his memoir begins: “An acquaintance, a man not known for his wide reading, not long ago asked me. . . .” He is now at the age when writers ponder their unwritten books, their unmet goals. Did Epstein accomplish everything he wanted? His vanity would probably say no, but a vast, impressive body of work says otherwise.

In a way, that’s his true autobiography, a keen record of his thoughts and values, passions and prejudices. He is revealed in every line and between the lines, as all writers are. And who, exactly, is revealed? Above all, a paradox: a man of intense likes and dislikes, in love with life yet bitterly disappointed by it, fond of friendship yet wary of intimacy. In the end, a true maverick, who has kept faith with himself as few of us manage to do in life.

Suggested Reading

People of the Book World

"The Jewish market has become quite a good one,” a Knopf editor observed; even the “goy polloi” were buying, wrote another staffer.

Jokes: A Genre of Thought

Three people are required to perfect a joke: one to tell it, one to get it, and a third not to get it.

As American as Augie March

Once again, Maya Arad marries the metafictional play of Nabokov with the moral warmth of Jane Austen.

Light Reading

Stoicism and the human heart.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In