Jokes: A Genre of Thought

Epicurus (341–270 B.C.E.), the Greek philosopher and founder of the school of Epicureanism, may also have been the world’s first shrink. Along with a cosmology and an ethics, Epicurus had a program for stemming anxiety, a four-step method for achieving serenity. Here are the steps:

1. Do not believe in God or the gods. Most likely they do not exist, and even if they did, it is preposterous to believe that they are watching over you and keeping a strict accounting of your behavior.

2. Do not worry about death. Death is oblivion, a condition not different from that of your life before you were born: an utter blank. Not to worry about heaven or hell; neither exists—after death there is nothing, nada, zilch.

3. As best you are able, forget about pain. Two possibilities here: Either it will diminish and go away, or it will get worse and you will die. Should you die, hakuna matata, for death, as we know, presents no problem, being nothing more than eternal dark, dreamless sleep.

4. Do not waste your time attempting to acquire luxuries, whose pleasures are certain to be incommensurate with the effort required to obtain them. From this it follows that ambition generally—for things, money, fame, power—should also be foresworn. The game, quite simply, isn’t worth the candle.

To summarize: Forget about God, death, pain, and acquisition—and your worries are over. I’ve not kitchen-tested this program myself, but my guess is that, if one could bring it off, it might just work. “Live the unnoticed life,” as Epicurus advises, and serenity will be yours—unless, that is, you happen to be Jewish.

I have known brilliant, stupid, flashy, dull, savvy, foolish, sensible, neurotic, refined, vulgar, wise, nutty Jews, but I have yet to meet a serene Jew, and I’m inclined to think there may never have been one. Marcus Aurelius, on visiting Palestine in 176 C.E., remarked: “O Marcomanni, Quadi, and Sarmatae, at last I have found people more excitable than you.”

Jewish habits of thought, featuring irony, skepticism, and criticism, taken together, further preclude serenity. These habits derive from Jewish history and personal experience. An Irish friend then in his nineties once asked me if there were any Yiddish words that weren’t critical. I told him there must be some, though I did not know them. Even words that might seem approbative, like chachem for wise man, with the slightest turn take on an ironic twist. “No great chachemess, Hannah Arendt,” my friend Edward Shils used to say when Ms. Arendt’s name came up.

The quest to grasp Jewish character, both on the part of Jews and on that of others, has been endless and is probably unending. Might Jewish humor offer a helpful clue? What is it about the kind of jokes Jews tell and appreciate, and about jokes featuring Jews as well as their appetite for humor, that is notably, ineluctably Jewish?

Great though the Jewish penchant for jokes is, Jews are of course not alone in joke-telling. In one of her essays the classicist Mary Beard cites the joke anthology Philogelos (Laughter Lover), a 4th-century work written in Greek but widely promulgated in Rome. Included in the Philogelos, according to Professor Beard, are “jokes about doctors, men with bad breath, eunuchs, barbers, men with hernias, bald men, cuckolds, shady fortune tellers, scholars and intellectuals and more of the colorful (mostly male) characters of Roman life.” Keith Thomas, in a lecture titled “The Place of Laughter in Tudor and Stuart England,” notes that “jokes are a pointer to joking situations, areas of structural ambiguity in society itself; and their subject matter can be a revealing guide to past tensions and anxieties.” About past—also present—tensions and anxieties, Jews know a thing or two.

The English philosopher Simon Critchley, in his book On Humour, writes that jokes help us to see our lives “as if we had just landed from another planet.” Critchley adds that “the comedian is the anthropologist of our humdrum everyday lives,” who helps us to see them in effect from the outside. He calls every joke “a little anthropological essay.” I have myself long thought of jokes, at least the more elaborate and better ones, as short stories.

Here is a joke told me by Saul Bellow:

Yankel Dombrovsky, of the shtetl of Frampol, is 42 years old, unmarried, shy generally, frightened of women in particular. Recently arrived from the neighboring shetl of Blumfvets is Miriam Schneider, a young widow. A Jewish bachelor being a shandeh, or disgrace, a meeting is arranged between Yankel and Miriam Schneider. Terrified, Yankel turns to his mother beforehand for advice.

“Yankel, darling son, please not to worry. All women like to talk about three things. They like to talk about family, about food, and about philosophy. Bring these up and I’m sure your meeting will go well.”

Miriam Schneider turns out to be 4’8″, weighs perhaps 230 pounds, and has an expressionless face.

Oy, thinks Yankel, oy and oy. What was it Mama said women like to talk about? Oh, yes, food.

“Miriam,” he asks in a quavering voice, “Miriam, do you like noodles?”

“No,” says Miriam, in a gruff voice, “I don’t like noodles.”

Veh es meer. What did Mama say? Family, that’s right, family.

“Miriam,” he asks, “do you have a brother?”

“Don’t got no brother,” Miriam replies.

Worse and worse. What was the third thing Mama said? Philosophy. Oh, yes, philosophy.

“Miriam,” Yankel asks, “if you had a brother, would he like noodles?”

Three people are required to perfect a joke: one to tell it, one to get it, and a third not to get it. For those who might have missed it, the object of this joke, of course, is philosophy, especially contemporary academic philosophy. Saul Bellow told me this joke when we were discussing the career of an Oxford philosopher. Bellow had a strong taste for jokes, but, unlike me, he had the patience to hold back telling them until the occasion arose when they made or underscored a point. His wit was generally more free range, sparked by the occasion. Once, walking together through the Art Institute of Chicago we passed Felice Ficherelli’s painting Judith with the Head of Holofernes, about which Bellow remarked, “That’s what you get for fooling with a Jewish girl.” I, upon hearing what I take to be a good joke, am more like the yeshiva boy running through the village exclaiming, “I have an answer. I have an answer. Does anyone have a question?” I need to tell the jokes to friends as soon as possible. Freud, about whose thought there cannot be too many jokes—the best is Vladimir Nabokov’s characterization of it as “Greek myths hiding private parts”—once said that a fresh joke is good news. The good news is that someone is thinking. Jokes, superior ones, are a genre of thought.

As such the genre is best maintained in the oral tradition. When I tell the “if you had a brother, would he like noodles?” joke, I do so, when speaking in Yankel’s voice, in a tremulous greenhorn English accent, and, when speaking in Miriam’s voice, in a tone of gruff insensitivity. I like to think performance improves the joke by perhaps 20 percent. Without voice and gesture to accompany them, jokes on paper, or as is now more common on a computer or cell phone screen, are a distant second best.

The first joke in S. Felix Mendelsohn’s The Jew Laughs: Humorous Stories and Anecdotes (1935) is about the result of telling a joke to a muzhik, a baron, an army officer, and a Jew. In different ways the first three fail to understand the joke, and the Jew, who alone gets it, replies that “the joke is as old as the hills and besides, you don’t know how to tell it.” Michael Krasny, early in his Let There Be Laughter: A Treasury of Great Jewish Humor and What It All Means, notes that “there is an old saw about how every Jew thinks he can tell a Jewish joke better than the one who is telling the joke.” Old saw it might be, but one with a high truth quotient. Alongside several of the jokes in Krasny’s collection, I noted, “my version is better.”

I made similar markings in the margins of William Novak’s Die Laughing: Killer Jokes for Newly Old Folks, a collection of jokes about aging and about being older generally. Many of these, in the nature of the case, are variants of gallows humor. They touch on too-lengthy marriage, what the French call the desolation generale of the body, sexual diminishment, physicians, the afterlife, and more. In 1981 Novak had produced, along with Moshe Waldoks, a collection called The Big Book of Jewish Humor. The jokes in Die Laughing have, perhaps out of fear of redundancy with his earlier book, been dejudaized, some to less than good effect. The punchline of the joke about the fanatical golfer who returns home late from his regular golf date because his partner and dearest friend died on the golf course early in the round is a case in point. In his explanation to his wife for his tardiness in returning home he explains that for several holes after his friend’s death “it was hit the ball, drag Bob, hit the ball, drag Bob.” The joke is much improved if Bob is named, as in the version in which I originally heard the joke, Irving. Novak tells the joke about the parsimonious widow who, learning that the charge for newspaper obituaries is by the word, instructs the man on the obit desk to print “O’Malley is dead. Boat for sale.” The joke is better, though, in the Jewish version, as “Schwartz dead. Cadillac for sale,” and is even one word shorter, thereby saving Mrs. Schwartz a few bucks.

Michael Krasny has a popular radio interview show on the NPR affiliate in San Francisco and is a university professor of English and American literature. Out flogging books of my own, I have twice been on his show and know him to be highly intelligent, cultivated, and good at his job. I’ve also met William Novak, who, along with being a collector of jokes, is, if an oxymoron be allowed, a well-known ghostwriter. He wrote the autobiographies of, among others, Lee Iacocca, Nancy Reagan, Oliver North, and Magic Johnson. Around the time I met William Novak I mentioned to my editor Carol Houck Smith that he was working on the autobiographies of Tip O’Neill and the Mayflower Madame. “Dear me,” she said, “I hope he doesn’t get his galleys mixed up.”

Both Messrs. Krasny and Novak’s books are filled with excellent jokes. I might wince slightly at the rare oral sex joke in Die Laughing, but, as Novak remarks after telling one such joke, “Too crass? You should see the ones I left out.” Michael Krasny has a weakness for name-dropping. He mentions, among several other drops: “Steve Jobs was someone I liked”; “my sweet friend Rita Moreno”; “my friend the novelist Isabel Allende”; and recounts an afternoon on which he kept Dustin Hoffman in stitches with Jewish jokes at a meeting with him and the director Barry Levinson. Myself the author of a book on snobbery, perhaps I am unduly sensitive to name-dropping, as I remarked over lunch the other day to my good friend Francis, you know, the Pope.

Michael Krasny and William Novak are men of good sense who wish only to bring pleasure to their readers, and both do. Novak doubtless shares with Krasny the latter’s wholly commendatory conservatory hope that the jokes and humor he loves “will remain an ongoing part of many lives for, well, you know, at least the next few thousand years.”

The problem is in the nature of their enterprise: the recounting of one joke after another. Krasny, to be sure, interlards his jokes with anecdotes from his personal experience and offers occasional interpretations of his jokes. Novak introduces his separate joke categories with brief and unfailingly amusing essays. Still, as a character in an Isaac Bashevis Singer story says, “You can have too much even of kreplach.”

In our meetings I have no recollection of exchanging jokes with Michael Krasny or William Novak, and I’m glad of it, for as Jokey Jakeys, as I think of habitual Jewish joke-tellers, things might have gotten competitive, and hence mildly abrasive. Jokey Jakeys like to hear a swell joke, but not as much as they love to tell one.

Here is a joke that appears in neither Michael Krasny’s nor William Novak’s book:

Sam Milstein is told his wife, now in the hospital, is dying. When he arrives, she asks him, in the faintest whisper, if he will make love to her one last time. He mentions the unseemliness, not to mention the awkwardness of his doing so—the wires, the tubes, and the rest—but she insists, and so he goes ahead.

Lo, that same evening, mirabile dictu, Sylvia Milstein’s vital signs rise; the next day she is taken off her respirator; and three days later she returns home in full health. Her family throws a party to mark her miraculous return to normal life. Everyone is delighted and immensely cheerful, except her husband Sam, who is clearly depressed.

“Sam,” a friend says, “your beloved wife has returned from near death. Why so glum?”

“You’d be glum too,” Sam replies, “if you could have saved the life of Eleanor Roosevelt and you never even lifted a finger.”

That joke is immitigably, irreducibly, entirely Jewish. Sam cannot be Bob, nor the Milsteins the O’Malleys. As for what is so Jewish about it, I should answer, in a word, everything: the politics, the depression, even the sex.

A question Michael Krasny asks but doesn’t quite fully answer is, Why are Jews so funny? Jews are like everyone else, of course, only more so. They have what Henry James called “the imagination of disaster.” Optimism is foreign to them. They find clouds in silver linings. If they do not court suffering, neither are they surprised when it arrives. They sense that life itself can be a joke, and one too often played upon them. They fear that God Himself loves a joke.

Adam, alone in the Garden of Eden, brings up his loneliness to God.

“Adam,” the Lord says, “I can stem your loneliness with a companion who will be forever a comfort and a consolation to you. She, this companion—woman, I call her—will be your friend and lover, helpmeet and guide, selfless and faithful, devoted to your happiness throughout life.

“But Adam,” says the Lord, “there is going to be a price for this companion.”

When Adam asks the price, the Lord tells him he will have to pay by the loss of his nose, his right foot, and his left hand.

“That’s very steep,” says Adam, “but tell me, Lord, what can I get for a rib?”

That joke is of course entirely unacceptable today; it is anti-woman, misogynist, politically incorrect. Michael Krasny brings up political correctness in passing, but in our day political correctness, in its pervasiveness, is the great enemy of joke-telling and of humor in general. Consider a simple joke Henny Youngman used to tell: “A bum came up and asked me for 50 cents for a cup of coffee. ‘But coffee’s only a quarter,’ I said. ‘Won’t you join me?’ he answered.” Today there are no bums, only homeless people. As soon as one sanitizes the joke by beginning, “A homeless person came up to me . . .” the joke is over and humor has departed the room.

Pervasive though political correctness has become, it, like affirmative action, does not apply to the Jews or to Jewish jokes. Anti-Semitic jokes abound, not a few told by Jews. All play off Jewish stereotypes, some milder than others. The four reasons we know Jesus was Jewish, for example, are that he lived at home till he was past 30, he went into his father’s business, he thought his mother was a virgin, and she (his mother) treated him as if he were God. Fairly harmless. But then there are the world’s four shortest books: Irish Haute Cuisine, Great Stand-Up German Comics, Famous Italian Naval Victories, and—oops!—Jewish Business Ethics.

What we need is not more anti-Semitic jokes, but more jokes about anti-Semites:

A Jew is sitting in a bar, when a man at the other end, three sheets fully to the wind, offers to buy drinks for everyone at the bar, “except my Israelite friend at the other end of the bar.”

Twenty minutes later, the same man instructs the bartender to pour another round for the house, excluding, of course, “the gentleman of the Hebrew persuasion at the end of the bar.”

A further 15 on, the man asks for one more round for everyone, “not counting, of course, the follower of Moses who’s still here, I see.”

Finally exasperated, the Jew calls down to the drunk, “What is it you have against me anyway?”

“I’ll tell you what I have against you. You sunk the Titanic.”

“I didn’t sink the Titanic,” the Jew says, “an iceberg sunk the Titanic.”

“Iceberg, Greenberg, Goldberg,” says the drunk, “you’re all no damn good.”

Michael Krasny remarks that the standard source ascribed to Jewish humor is “located in a kind of masochism but also in suffering. It is self-deprecatory and self-lacerating, and it sees Jews as outsiders, marginal people, victims.” A good definition, that, of the comedy of Woody Allen, with psychoanalysis jokes added. But Krasny also sees in these Jewish jokes “a strain of celebration” and cites Jewish American princess, or JAP, jokes as an example. A brilliant JAP bit I know is that performed by the comedian Sarah Silverman, impersonating a faux Jewish American princess, in which she invents a niece who claims to have learned in school that during the Holocaust, 60 million Jews were killed. In her best ditzy JAP voice, Silverman corrects the child, saying that not 60 but six million Jews were killed, adding, “60 million would be something to worry about.”

A few categories of superior Jewish jokes failed to find their way into the Krasny or the dejudaized Novak volume. Jewish waiter jokes are, for one, missing. Allow me to supply merely the punchlines of a few: “Vich of you gentlemen vanted the clean glass?” “You vanted the chicken soup, you should’ve ordered the mushroom barley.” Another missing category is jokes about German Jews, or yekkes, as they are known, for the formality that did not allow them to remove their suit jackets in public. “What’s the difference between a yekke and a virgin?” one such joke asks. The answer is, “A yekke remains a yekke.” And in the category of out-of-control Jewish wifely extravagance the winner is Rodney Dangerfield’s “A thief stole my wife’s purse with all her credit cards. But I’m not going after him. He’s spending less than she does.”

Of the endless category of synagogue jokes, Michael Krasney tells the superior joke about the rabbi who rid his shul of mice by luring them onto the bimah with a wheel of cheese, and while there, bar mitzvahing them all, whereby they never returned. I wonder if he knows my friend Edward Shils’s favorite joke in this, the synagogue category:

A peddler, just before sundown, arrives at the study of the rabbi of the shtetl of Bobrinsk. Three men are in the study at the time. The peddler asks the rabbi if he will keep his receipts over Shabbat, when an observant Jew is prohibited from having money on his person. The rabbi readily agrees.

Next day, after sundown, the peddler appears in the rabbi’s study to collect his money. The same three men are there.

“What money?” the rabbi asks.

“The money I gave you to hold for me last night,” the peddler says. “These men were there. They will remind you.”

The rabbi turns to the first man. “Mr. Schwartz, did this man leave any money with me yesterday?”

“I have no recollection of his having done so, rebbe,” Schwartz says.

“Mr. Ginsberg,” the rabbi asks, turning to the second man, “do you recognize this man?”

“Never saw him before in my life,” Ginsberg says.

“Mr. Silverstein, what do you think about this?”

“The man’s a liar, rebbe,” says Silverstein.

“Thank you, gentlemen,” says the rabbi. “Now if you will excuse me I shall deal with this man alone.”

After the three men depart, the rabbi goes to his safe, removes the peddler’s money, and hands it to him.

“Rebbe,” says the peddler, “why did you put me through all that?”

“Oh,” answers the rebbe, “I just wanted to show you the kind of people I have in my congregation.”

When Edward told me this joke, which he much enjoyed, I assumed that he had in mind, as analogues to Messrs. Schwartz, Ginsberg, and Silverstein, his colleagues on the Committee on Social Thought at The University of Chicago.

In Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, Freud wrote, “I do not know whether there are many other instances of a people making fun to such a degree of its own character [as do the Jews].” I myself cannot think of any. Who but the Jews joke about their mothers, their religious institutions (“Reform Judaism, isn’t that the Democratic Party platform with holidays added?”), their own attitudes of compromise and resignation, their nouveau riche, their domineering wives, their uxorious husbands, the way their enemies think of them, and more? The Irish joke about themselves—an Irish friend not long ago told me that the famous Irish charm is inevitably lost only on the Irish themselves—but nowhere near so thoroughly as do the Jews, who find almost everything about themselves a source of humor.

“How odd of God to choose the Jews” runs a ditty composed by an English journalist named William Norman Ewer, to which various responses have been offered, perhaps the most amusing among them being “because the goyim annoy him.” Chosen the Jews may have been, but the everlasting question remains: chosen for what? If pressed to come up with a single theme playing through the Old Testament, I should say that theme would be testing, the relentless testing by God of the Jews from Abraham through Saul, David, and Solomon to Job and beyond. God submits the Jews to tests and trials of a kind that no other religion, so far as I know, puts its adherents through, including, some in our day might say, unrelenting anti-Semitism. Might it be, to revert to an earlier point, that a key reason there are no serene Jews is that every Jew somewhere in his heart knows that, no matter how well off he is or how righteously he has lived, further tests await.

Freud felt all jokes at bottom had for their purpose, however hidden, either hostility or exposure—all jokes, in other words, for him are ultimately acts of aggression or derision. I don’t happen to believe that. Michael Krasny quotes Theodor Reik, in Jewish Wit, remarking that all Jewish jokes are about “merciless mockery of weakness and failing.” I don’t believe that, either. What I do believe is W. H. Auden saying that the motto of psychology ought to be “Have you heard this one?”

Jewish jokes are richer and more varied than any single theory can hope to accommodate. In No Joke, her excellent study of Jewish humor, Ruth Wisse notes that “Jewish humor at its best interprets the incongruities of the Jewish condition.” That condition has imbued Jews with a style of thought when faced with received opinions and conventional wisdom. Among their grand thinkers, and their everyday ones, are, or ought to have been, those trained by life to think outside the box—or, as the Jew in me, having written out that cliché, needs to add, outside the lox. Jewish jokes are a victory over thoughtlessness.

Maury Skolnik tells his friend Mel Rosen, “Two Jews, each with a parrot on his shoulder, meet outside their synagogue, when . . .”

Rosen interrupts: “Maury, Maury, Maury, don’t you know any but Jewish jokes?”

“Of course I do,” Skolnik replies. “It’s autumn in Kyoto, two samurai are standing in front of a Buddhist temple. The next day is Yom Kippur . . .”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Godly Guardrails and Secular Assumptions

Ilana M. Horwitz convincingly argues that religious students are high achievers. But what’s the special sauce that makes it so, and who gets to decide what counts as an achievement?

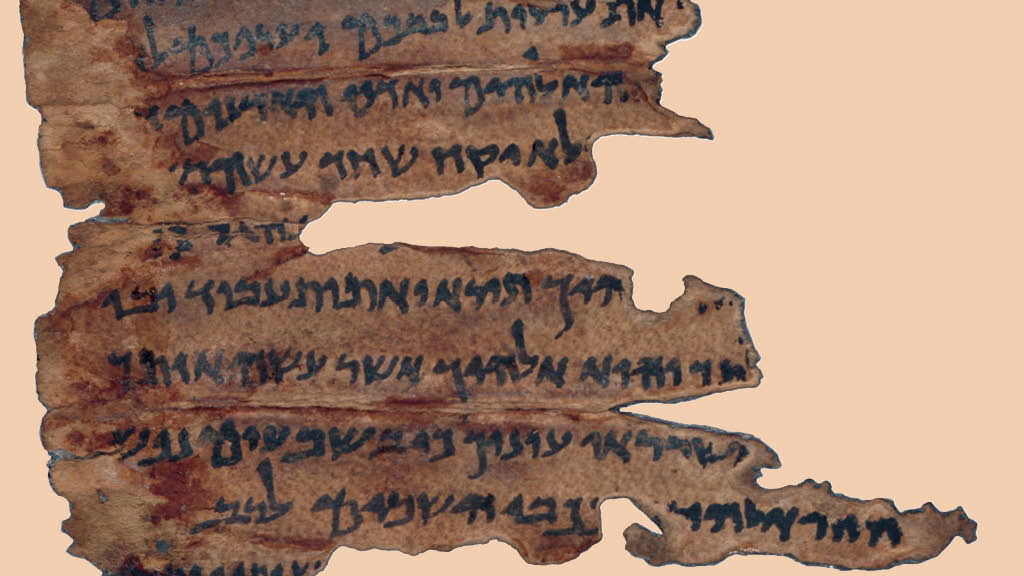

Origin Stories

If the Israelites of the Hebrew Bible weren't Jewish, when did Judaism begin?

Secret Chord

When the Yom Kippur War started, Leonard Cohen left the Greek island of Hydra and headed for Tel Aviv. He was coming in solidarity but he was also looking for a way to sing again.

The Treasure of the Jews

The seductive idea that the real Jerusalem lurks somewhere beneath the actual city, with its grocery stores, traffic, and inconveniently present residents, has motivated archaeologists and journalists since the 1800s.

gwhepner

JEWISH JOKES

You need at least four people for a joke that's Jewish,

one to tell it, one to get, one who doesn't

get it, and a fourth who tells you that you mustn't

tell it, since it is so old it's not even newish.

A fifth is useful, he's the one who analyzes,

as Judith analyzed the head of Holofernes,

the joke which he will surely tell you he despises,

and tell one he thinks funnier, about attorneys.

[email protected]

sbeinfeld

Joseph Epstein needs to brush up on his Yiddish. A wise man is a "chochem", not "chachem", though Edward Shils's "chachemess" is OK. "Veh es meer" is a flawed transcription of "vey iz mir" A propos Shils: his joke about the three untruthful synagogue members exposed by the Rabbi is actually a variant of the story Sholom Aleichem records as being told to him at his own expense. A Jewish traveler at a train station is persuaded to miss the last train before the Sabbath in order to complete a minyan. The traveler is put up for the night, urged to taste his wife's cooking and so on for several days. When the traveler finally leaves, he is presented with a detailed bill. The traveler is outraged but agrees to go to the town Rabbi to settle the case. The Rabbi solemnly rules he must pay. When the traveler grudgingly hands over the money, the local man indignantly refuses to take it. When he asks what the demand for payment was all about, he is told--"I didn't want you to leave town without seeing what kind of Rabbi we have." Sholom Aleichem was for three years a town "rabiner" (state-appointed rabbi).

bikerabbi

מזל טוב You have prooved his above citation: "Michael Krasny, ... notes that “there is an old saw about how every Jew thinks he can tell a Jewish joke better than the one who is telling the joke.”"

:-)