Scattered Seeds: The Origins of Diaspora

In the late third century BCE, a group of scholars working on a translation project in Egypt invented a Greek word that would change the course of Jewish—and arguably human— history.

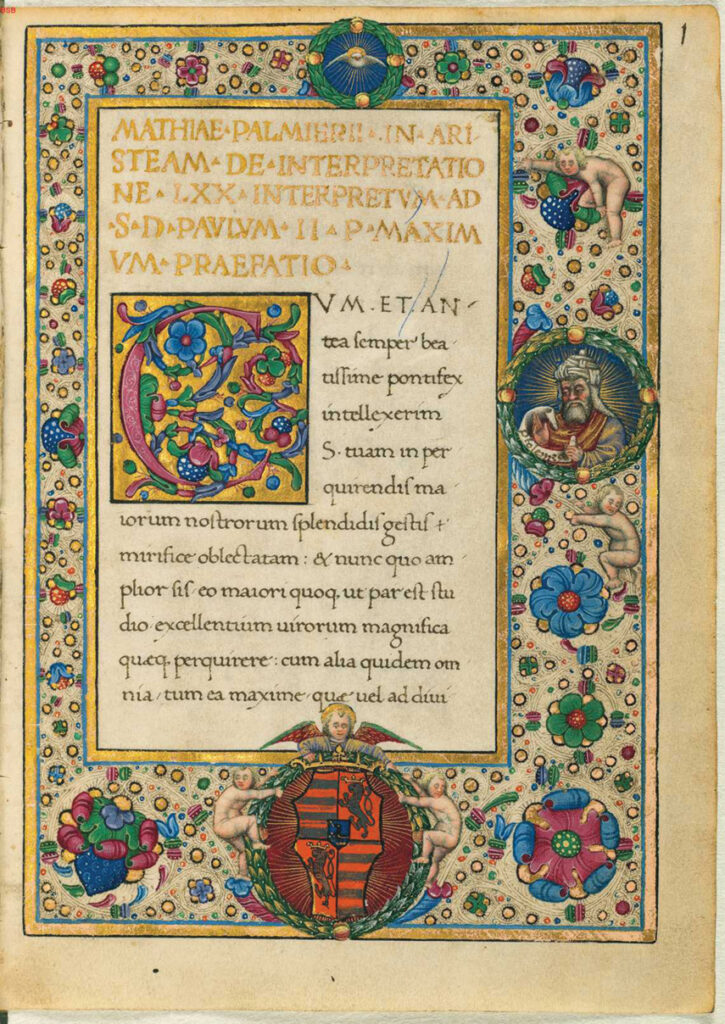

The project was to render the Hebrew Torah into Koine Greek. According to a second-century BCE novella called the Letter of Aristeas, the Egyptian pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus (the son of Alexander the Great’s general) commissioned a Greek translation of the Torah for the royal library. He dispatched envoys to Eleazar the high priest in Jerusalem who sent back six translators from each of the twelve tribes, seventy-two in all. They were sequestered just off the coast of Alexandria on the island of Pharos and completed the translation in seventy-two days, which is why it is called (rounding down) the Septuagint, which means “seventy.” There likely weren’t seventy-two translators, they probably didn’t come directly from Jerusalem, the Septuagint was intended for Greek-speaking Jews and not the royal library, and the translation took much longer. But Aristeas is correct that the project was extraordinarily important for Jews who lived under Hellenistic rule outside the Land of Israel and for the Judean Jews who pondered the significance of Jewish life abroad.

When the Septuagint’s translators arrived at a verse in which Moses predicts that the Israelites would become a horror (za’ava) before the foreign nations if the terms of God’s covenant were violated, they searched for the right Greek word to describe the Israelites’ condition. Although they were not emissaries of the high priest of Jerusalem, the translators seem to have had personal ties to the Land of Israel, which influenced the word they chose. In fact, it was one that didn’t yet exist in that form: “diaspora,” from dia-, meaning over or through, and -sperein, meaning to scatter like seeds (the modern word “spore”is also derived from the verb).

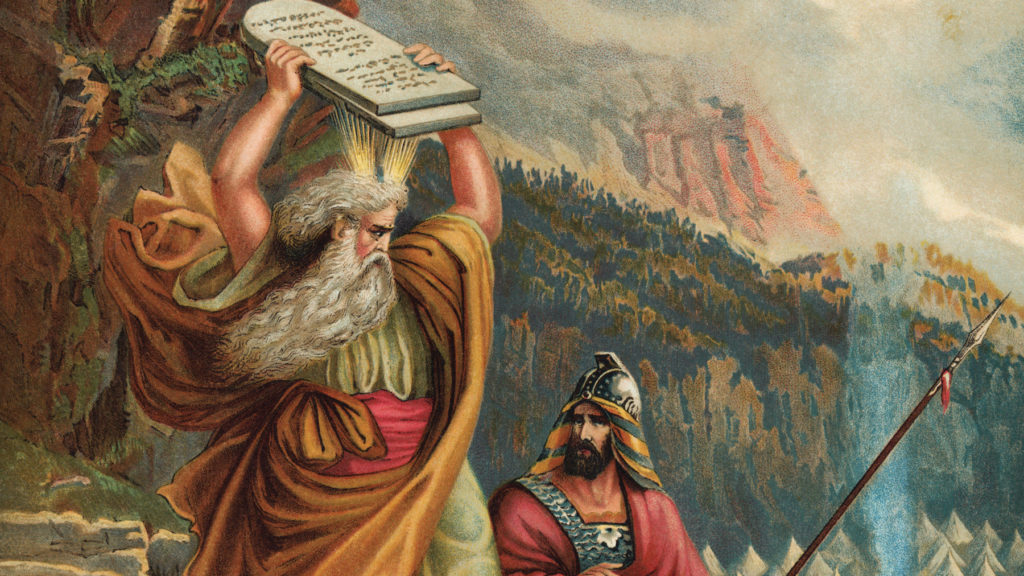

The crucial verse in Deuteronomy is one in which Moses predicts that if the Israelites violate the covenant, God will respond by ensuring that they are vanquished by their enemies and humiliated before other nations. The New JPS translation reads:

The LORD will put you to rout before your enemies; you shall march out against them by a single road, but flee from them by many roads; and you shall become a horror [za’ava] to all the kingdoms of the earth. (Deut. 28:25)

Eleven verses later, Moses clarifies the nature of this humiliation by forecasting that the people will be expelled from their land: “The Lord will drive you, and the king you have set over you, to a nation unknown to you or your fathers” (Deut. 28:36). The Septuagint scholars read this horrifying vision of expulsion back into the earlier verse, and za’ava became “diaspora.” Thus, the Septuagint’s version of Deuteronomy 28:25 (in English) reads:

May the Lord give you slaughter before your enemies; you shall go out against them by one way and flee from them by seven ways. And you shall be in dispersion [diaspora] in all the kingdoms of the earth.

So diaspora was, in the first place, a curse. The people of Israel would be scattered like seeds that could survive only in their native soil. And yet the Jews who were dispersed throughout the Hellenistic world for whom the Septuagint translators were producing this Greek Bible did not seem to be living in horror and disgrace. They didn’t seem to be suffering at all. Instead, they enthusiastically took advantage of myriad opportunities to participate in Hellenistic life while adhering to their ancestral laws.

The translation of za’ava as “diaspora”did not reflect a historical reality so much as it polemicized against it. Why, then, did the authors of the Septuagint associate divine anger with dispersion? The answer to this question lies in events that took place three centuries before the Septuagint was composed.

When the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar began to force Judahites out of their land in 597 BCE, prophets such as Jeremiah promised that the exile (golah) would eventually come to an end, and with it, a period of peace and independence would begin, signifying a reconciliation between God and the people. However, when the Persian King Cyrus defeated Babylon in 539 BCE and permitted the Judahites to return to their homeland and rebuild the Second Temple, it became clear that these prophecies would not be entirely fulfilled. Those who returned to Judah now lived in the Persian province of Yehud and were subjects of the Persian empire. Moreover, most of the exiles did not return. They stayed where they were or migrated to other regions of the empire.

As Judahites (or Judeans, as English-speaking scholars now refer to the Yehudim) discovered that the prophetic promises of their scriptures had not been completely fulfilled, they faced a major theological question: Was the exile over, or was it ongoing? Most Judeans living outside their homeland probably believed that the exile had indeed come to an end. Proof for this lay in the fact that they enjoyed relative freedom and success. Judeans in the Land of Israel, however, disagreed. The exile was ongoing, but it was no longer a golah imposed by God on all of Israel. It was a national disgrace perpetuated by the people who chose not to return. This was the horror that the translators of the Septuagint invented the word “diaspora” to capture. In doing so, they also invented a concept that split the Jewish people in half in a way that the earlier concept of exile never did.

Although the Septuagint’s first reference to “diaspora”links Israel’s expulsion with public shame, its second reference appears shortly afterward in the comforting words of Deuteronomy 30:4–5:

Even if your spread-out ones [nidaheha] are at the ends of the world, from there the LORD your God will gather you, and from there He will fetch you. And the LORD your God will bring you to the land that your fathers possessed, and you shall possess it; and He will make you more prosperous and numerous than your fathers.

The translators of the Septuagint replaced the Hebrew nidaheha with “diaspora,” again asserting that the sinful Israelites would be dispersed to foreign lands controlled by their enemies. Here, however, God makes a key promise, one that Jews living in Egypt in the Hellenistic era may not have viewed as particularly comforting: One day, the diaspora would end.

Of the fifteen appearances of the word “diaspora” in Second Temple literature, thirteen of these appear in works that were preserved in the Septuagint: Deuteronomy, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Daniel, Nehemiah, Judith, 2 Maccabees, and Psalms. In most of these works, the word“diaspora” enforces the association between living outside the Land of Israel and the experience of shame.

Take, for instance, an apocalyptic passage preserved in the book of Daniel, which is notable for being one of the first references to resurrection in early Jewish literature. The passage imagines that individuals will take on a new form of existence after death, though the nature of this form will vary according to one’s piety:

Many of those that sleep in the dust of the earth will awake, some to eternal life, others to reproaches, to everlasting abhorrence. (Dan. 12:2)

What kind of shame and contempt will those who do not merit everlasting life experience? The Septuagint’s translation of this verse makes the answer clear: It will be diasporic:

And many of those who sleep in the flat of the earth will arise, some to everlasting life but others to shame and others to dispersion and contempt everlasting (eis diasporan). (Dan. 12:2)

The Judean association between diaspora and shame coagulated over time, even in works that didn’t use the word. The book of Baruch, a work that is thought to have been composed in the late second century BCE by a Judean scholar or scholars, opens with Jeremiah’s scribe reading a letter to Babylonian exiles. This letter, which is to be dispatched to Judahite leaders that remain in Jerusalem, asks them to pray on behalf of an exiled people:

The Lord our God is in the right, but there is open shame on us and our ancestors this very day. All those calamities with which the Lord threatened us have come upon us. (Bar. 2:6–7)

Baruch, which describes how the Judahites responded to the catastrophe of exile, is best read as a fantasy that imagines exiled Judahites expressing a desperate desire to return to their homeland.

In a letter appended to 2 Maccabees, Jewish leaders in Jerusalem implore Jews living in Egypt in the late second century BCE to observe the holiday of Purification, which would later become known as Hanukkah. Its authors argue that this holiday commemorates not only the Hasmonean victory over the Syrian Greeks in 164 BCE but earlier miracles too. The letter preserves a prayer uttered by a high priest named Jonathan in the wake of one such miracle:

Gather together our scattered people [diaspora], set free those who are slaves among the nations, look on those who are rejected and despised, and let the nations know that you are our God. (2 Macc. 1:27)

In the letter’s closing lines, the Judean authors make a request of their fellow Jews in Egypt:

You would do well to keep the days too. It is God who has saved all his people, and has returned the inheritance to all, and the kingship and the priesthood and the sanctification, as he promised through the law. We therefore have hope in God that he will soon have mercy on us and will gather us from what is under heaven to his holy place, for he has rescued us from great evils and has cleansed the place. (2 Macc. 2:16–18)

These Judean documents suggest that God continues to show special favor to Jews who live near Jerusalem and the Temple Mount, but God also awaits the repentance of Jews in the diaspora, which will galvanize their ingathering and put an end to God’s disfavor.

How did diasporan Jews respond to the word “diaspora” and to the idea behind it? They barely responded at all. Few texts that were actually produced outside the Land of Israel during the Second Temple period ever express a longing for diaspora to end. The Jews did write novellas, wisdom texts, and poems that celebrated Jerusalem and its temple as the center of Jewish life. Yet these same texts make no distinction between the spiritual lives of Jews who live within the Land of Israel from those who live outside it. They also do not ask God to put an end to Jewish life outside the Land of Israel. Instead, they present Jews who live outside the Land of Israel as spiritual ambassadors who bring knowledge of God to the foreign nations.

One place we see this attitude expressed is in the Letter of Aristeas, in which Ptolemy’s request for a Greek translation of the Torah is met with Judean enthusiasm. The Jerusalem high priest Eleazar and the scholars he selects understand the value of the project and embrace the legitimacy of their Jewish kin in Egypt. The story culminates in a celebratory scene in which Ptolemy asks each scholar a question at a weeklong symposium-style feast and is amazed by the wisdom of their responses.

Egyptian Jews who read the Letter of Aristeas and the Septuagint it celebrates did not abandon their loyalty to the Temple. But they did ignore the notion that they lived in a state of divine disfavor, even if it was summed up in a word that existed in the only version of the Torah that most of them could read. By the early Common Era, most Jews living outside their ancestral homeland were certain that the divinely imposed exile, or golah, was a thing of the past, and the diaspora was a figment of Judean imagination.

Suggested Reading

Inside-Out

The boundaries between the biblical canon and the Apocrypha have seemed firm for a long time. But what if the walls aren’t that solid?

Law in the Desert

Studying the weekly portion with Jerome, Nachmanides, and others, the seemingly tedious parts of Exodus become compelling.

The Jewsraeli Century

Ben-Gurion declared that “with the creation of the state, we are standing on the edge of a new era. Not only in the life of the Jewish community in Israel, but . . . in the history of Judaism itself.” He was right, but not in the way he thought he would be.

Romancing the Exile

Shaul Magid’s counter-Zionism is not so much a political program as it is a utopian posture.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In