The Jewsraeli Century

In 1948, David Ben-Gurion declared that “with the creation of the state, we are standing on the edge of a new era. Not only in the life of the Jewish community in Israel, but—I believe—in the history of Judaism itself.” Ben-Gurion was right—Jews and Judaism have become increasingly “Israelized” throughout the 21st-century diaspora, but not quite in the way that he thought they would be, because Israeli Jewish identity is not what he thought it would be.

In their important, accessible new study, #Yahadutyisraelit: di’ukan shel mahapecha hevratit (#IsraeliJudaism: A Portrait of a Cultural Revolution), the prolific journalist-publisher Shmuel Rosner and the distinguished Tel Aviv University statistician Camil Fuchs sketch a portrait of Israeli Jewish identity based on data from a recent well-constructed and widely distributed survey. In doing so, they reveal a broad Israeli public that is far more traditional than Ben-Gurion, who envisioned the new Israeli as a Bible-quoting secularist who looked back with pride to the exploits of Bar Kokhba, imagined. Thus, almost all Israeli Jews, or a large majority of them, “attend Seders on the first night of Passover, observe Rosh Hashanah, celebrate Hanukkah, have Friday night dinners . . . and perform circumcisions. A large majority of the Jews believe in God (78 percent), if not all the time and not in perfect faith.”

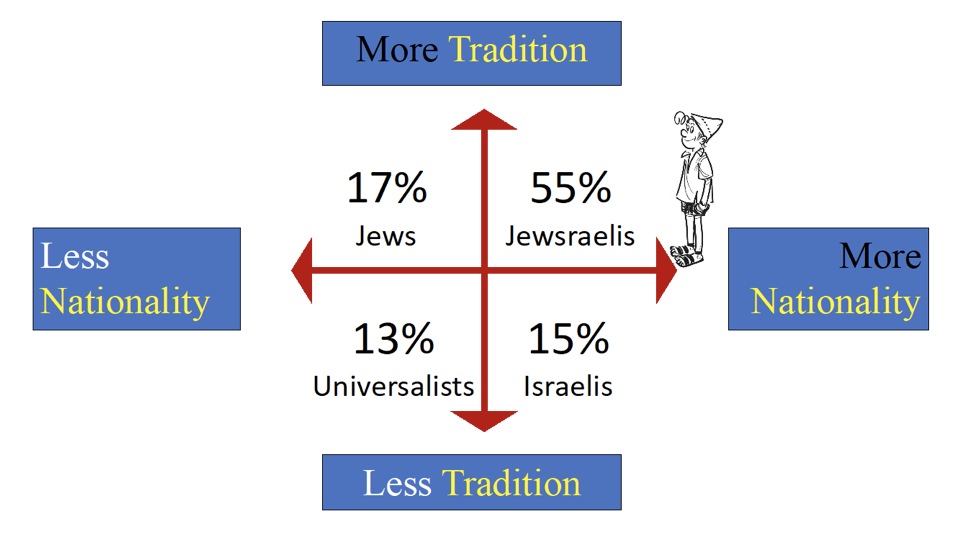

What distinguishes these Jews from all who came previously is their complete “mixing of Jewishness and Israeliness.” Rosner and Fuchs dub them “Jewsraelis,” practitioners of a new “IsraeliJudaism,” and show that they now comprise 55 percent of the Israeli Jewish population. They divide the rest of Israel Jews into three groups: those who are more traditional but less nationalistic (thus, for instance, they celebrate Shabbat but not Yom Ha-atzma’ut), whom they simply call “the Jews” (17 percent); those who are more nationalistic but less traditional, “the Israelis,” including the old-style Ben-Gurion Labor Zionists (15 percent); and those cosmopolitan universalists who profess little allegiance to either the State of Israel or Judaism (13 percent). (If you want to understand the base for Bibi Netanyahu’s Likud for the last decade and its coalition partners, look to the first two types of Israelis who make up almost three-quarters of the Jewish population.)

This new Jewish type, the Jewsraeli, is a patriotic nationalist for whom fighting for Israel and its safety (“at any cost”) is the ultimate Jewish creed: “The Israeli Jew practices Judaism like no previous Jew.” Israeli Judaism is “an amalgamation of tradition and nationality. In many cases it is very hard—maybe impossible—to determine where the Jew ends and the Israeli begins, or where the Israeli ends and the Jew begins.”

Such Israeli Jews are, of course, very different from their American and European cousins whose national identities have been more or less distinct from their religious ones since the Enlightenment and Emancipation. And yet, in an ironic if not paradoxical turn of history, it is just as Ben-Gurion predicted: The Jews and Judaism of the diaspora are increasingly and inevitably oriented toward Israel and its distinctive brand of civic religion. Moreover, this is true in both positive and negative ways: Israel is looked to as a source of pride, identity, and Jewish meaning, but the “Jewish question” has also, and with increasing virulence, become the “Israel question,” whether it is on the streets of Paris, in the British Parliament, or on American college campuses roiled by the controversies over the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement.

The Israelization of Judaism begins with the numbers. Of the 34 democracies in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Israel has by far the highest birth rate: about 3.14 children per woman. This is not just because of the fertility of the haredi (and religious Muslim and Druze) populations. Israeli women who describe themselves as secular or traditional but not religious have a birth rate higher than that found in any other OECD country. As the authors of a recent study note, “Israel’s exceptional fertility” is driven by its national culture:

Israel’s fertility is not only exceptional because it is high. It is exceptional because strong pronatalist norms cut across all educational classes and levels of religiosity, and because fertility has been increasing alongside increasing age at first birth and education—at least in the Jewish population. From an international perspective, these are atypical patterns.

Nowhere in the diaspora, outside of haredi communities, do Jews grow at such a fantastic rate, and, unsurprisingly, no Jewish culture in the diaspora has developed such a powerful formula for Jewish identity as the one developed in the State of Israel. Indeed, the most successful and celebrated program in promoting American Jewish identity is Birthright, which basically puts young American Jewish adults on a plane to Israel and introduces them to Jewsraelis.

Rosner and Fuchs’s Jewsraelis are certainly not the new Jews that Ben-Gurion expected, but they are similar in one crucial respect. Neither type is preoccupied with “Jewish survival,” nor are they concerned about the loss of Jewish identity. Judaism for the Israeli Jew is an undisputed given. Meanwhile, Jewish life in the diaspora is increasingly overshadowed by Israeli trials and triumphs. As Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove of Park Avenue Synagogue recently wrote:

These days, American Jews no longer debate who wrote the Bible. Instead, we argue about Israel. Israel is what brings us together and what tears us apart. We work to keep our relationship with Israel strong and are anxiety-ridden at signs of its weakening. We fear for our children’s encounters with anti-Zionism on campus, and we hope that they sign up for Birthright trips. The labels that delineate our denominations are no longer based on belief or observance—Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist—but on our views about Israel: AIPAC, ZOA, JVP, J-Street and the rest of the alphabet soup of Israel advocacy.

All over the world, Israeli politics, culture, economics, and religion are more and more identified with the Jewish people and Judaism itself. Indeed, as one of us (Yossi Shain) has argued in these pages, the orientation toward Israel is even more pronounced in Europe, where it has increasingly become a life question—should I make aliyah? should my children?—first in France and now in England, rather than the kind of policy question debated in Cosgrove’s distinctively American alphabet soup of organizations.

Since its early days, the State of Israel has claimed responsibility for “Jewish interests.” Seven decades later, Israel routinely and decisively speaks on behalf of the Jews throughout the world. And hatred of Jews is increasingly expressed as hatred of the State of Israel, a phenomenon that has existed since the state was founded but has recently become more pronounced. (In May 2019 the German Bundestag voted to define the BDS movement as anti-Semitic, because it “questions the right of the Jewish and democratic State of Israel to exist or Israel’s right to defend itself.”)

From the interminable “who is a Jew?” controversies to political negotiations over how the Holocaust is remembered, the State of Israel has become the most powerful arbiter of the Jewish identity and memory. This is not an unalloyed good—there were, for instance, strong arguments against the deal Prime Minister Netanyahu cut over Polish responsibility during the Holocaust—but it is inevitable. The Jewish center of gravity—demographic, cultural, religious, political, and even economic—is in Jerusalem, not New York. The unprecedented Jewish identity of Rosner and Fuchs’s Jewsraeli is central to this development.

Novelists often register social phenomena and trends before we social scientists discover them in our data sets, and this is certainly true of the new dominance of Israel in Jewish life. The leading contemporary American Jewish writers have all found themselves increasingly, if ambivalently, drawn to Israel and the impact of Israel’s sovereign life on the question of Jewish kinship and Jewish values.

The literary historian Morris Dickstein has written, “Until the early 1980s there was . . . little trace of the Jewish state in American fiction . . . American writers by and large were not Zionists . . . Israel was perhaps too insular to capture the imagination of assimilated writers.” By the last decade, it was an entirely different story. Michael Chabon, Nathan Englander, Jonathan Safran Foer, and Nicole Krauss have all found themselves exploring Jewish identity by turning to Israel. As Matti Friedman recently noted in these pages, “Jewish American writers of a few decades ago might have poked around the strange Jewish country in the Middle East, but they knew that the real literary action for them was back home. The novelists of 2017 don’t seem so sure.”

A character in Nicole Krauss’s novel Forest Dark says that “the Wealthy American, come to Israel to dip into the rich, authentic Jewish vein all those US dollars have gone to protect, so that he knows it’s still alive over here and doesn’t have to regret too much; come to turn himself on again in the bracing atmosphere of Middle East passion.” In Dinner at the Center of the Earth, Nathan Englander captures the American liberal Jewish conundrum in regard to Israel. His novel depicts progressive American Jews as caught in an insoluble dilemma. If they distance themselves from Israel, they wither as Jews, and if they take on or defend the Israeli point of view, they lose their status as liberals. As Friedman writes, “I don’t think anyone reading these books could miss their distance from the brash and rooted tone of ‘I am an American, Chicago-born.’ The center seems to have moved.” Indeed.

American Jewish identity, particularly but not only in its liberal form, evolved in a completely different historical and social context than the Israeli one, and yet American Jews cannot ignore Israeli Judaism. The relationship is not symmetrical. As Rosner and Fuchs show, the ordinary Jewsraeli tends to be indifferent to Jewish affairs in the diaspora, at least until there is a crisis in foreign affairs or an anti-Semitic attack.

None of which is to say that Israel or Israeli Jews have solved the problems of religion, state, and modernity. To the contrary, Israel culture and politics are perpetually caught in the tension between ardent nationalism and liberal democracy, between constant innovation and the demands of traditional halakha, and a dozen other versions of these tensions. For decades, the internal strife this engendered was contained mainly because of the Arab threat. That threat has changed in recent years as the region has become more chaotic and Israel has become stronger. But Israeli Jewish culture has also evolved, and the Jewsraeli identity that Rosner and Fuchs so ably limn has managed to hold the center and even command the world stage while maintaining the sense of Israel not only as a coherent, successful polity but as a family, albeit a troubled one.

The Israeli Jew’s strong sense that he has a home, and a place to come back to, allows him to move confidently and act in the world with comfort and a sense of security. If the Jewish 20th century was dominated by America, the 21st century shows every sign of being the Israeli century.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Hebraic America

When Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin sat down to design the Great Seal of the United States they both turned to the Bible.

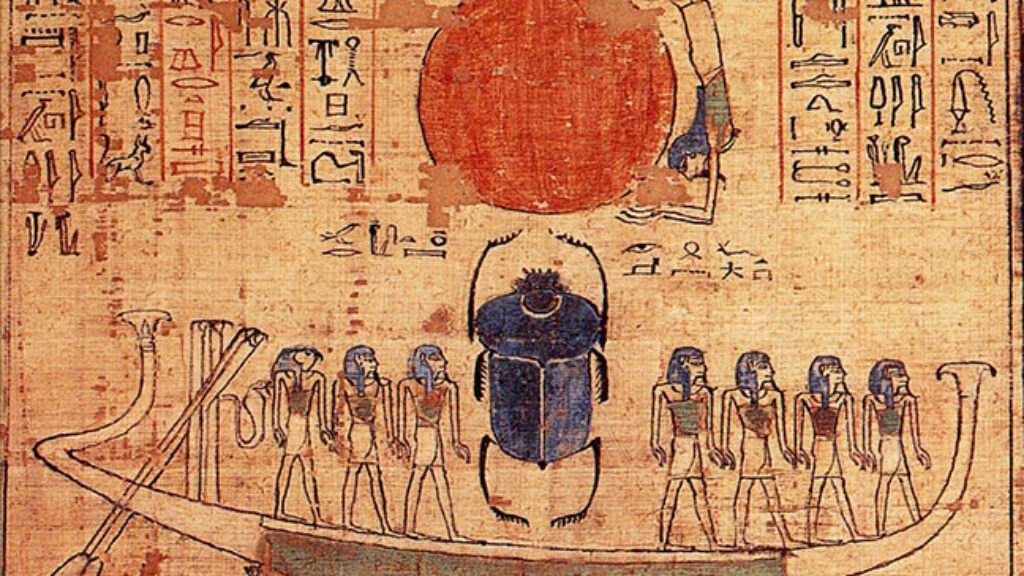

Exodus and Egyptology

The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel shows why the plagues were chosen and how the Israelites sang at the reed sea.

How Jews Were Modern

What’s a nice Jewish boy doing making bronze statues of tsars? And does it count as Jewish culture? Ahad Ha’am wanted to know and the Posen Foundation’s ambitious new survey raises the question afresh.

18 Questions with Dara Horn

Dara Horn’s new novel, Eternal Life, is out today. We caught up with her and asked her 18 questions.

Justin Jaron Lewis

Jewsraelism seems to depend on ignoring or denying the existence of non-Jews in Israel, and particularly the Palestinians. "Kulanu Yehudim!" -- we're all Jews here. This cannot last, unless the Palestinians give up their own sense of being a people tied to the land, or unless there is a fair and workable "two-state solution"; neither seems likely at present. But Judaism has survived other historical moments when the majority placed their faith in an illusion; if humanity survives, we Jews still have good hope of survival, generation after generation, יהיה מה שיהיה.

Hila

Oh for fuck sake, not everything in Israel is related to the conflict with the Palestinians. You want to talk about assimilations? Talk about the aliyot, especially the relatively recent former USSR members whose cultural identity is pretty divorced from Judaism.

Nothing about "Jewsraelism" depends on denying other ethnicities exist, no more than a Christian majority forces other ethnicities to give up their identity. The traditions are public and Jewish holidays dictate when you get a state-mandated break from school/service/work but nothing forces anyone to participate. Even the few laws that are more religious in nature are highly contested. Seriously, what are you even basing your argument on, Israel's online reputation?