Sundowning

Editor’s Note: Shortly before this article appeared in print, the book’s publisher moved the release date to June 2021.

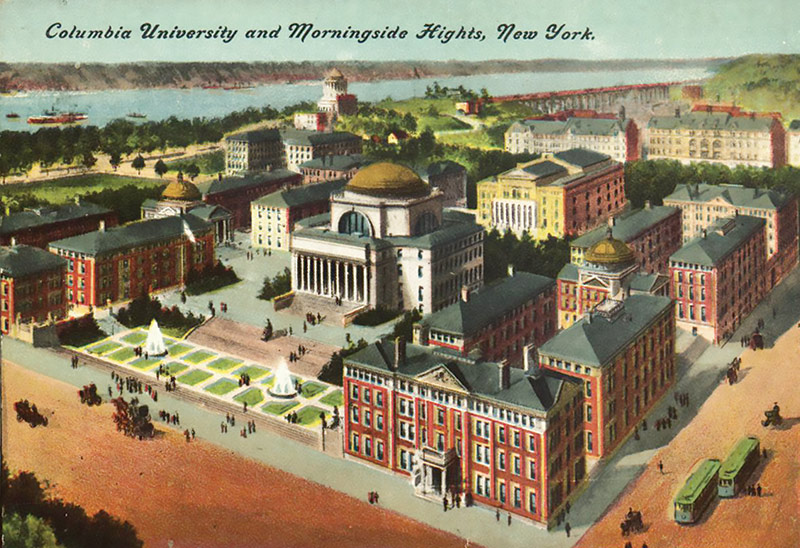

In the geography of Jewish New York, Morningside Heights has a definite moral and social identity, no less than the Lower East Side or Crown Heights. This Upper West Side neighborhood, anchored by Columbia University, evokes the high-minded, bourgeois liberalism that flourished among Jewish academics and intellectuals in the 20th century. Today, that worldview can feel a little outmoded and lacking in confidence; humanism with a Jewish inflection has been outflanked on both the left and the right by more aggressive cultural styles.

Joshua Henkin’s new novel, Morningside Heights, is a portrait of that milieu, an interrogation of its shortcomings and a eulogy for its passing, all in one. At the center of the story is Spence Robin, a star professor in the Columbia English department, where he has taught since the 1970s. He’s the kind of scholar who is famous enough to get a big advance for a popular book about Shakespeare, yet highbrow enough to feel guilty about it. The only TV allowed in his apartment is a small black-and-white set, which is usually hidden away. When he wins a MacArthur, his wife, Pru, throws a party to celebrate, but Spence dislikes the fuss: “You didn’t have to announce it to everyone,” he grumbles.

Many novels have been written about aging Jewish intellectuals, but Morningside Heights takes an unusual approach. The book’s main action begins in 2005, when Spence, still only in his fifties, is diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s. Henkin charts Spence’s rapid decline in painfully authentic detail. At first, he merely loses his train of thought while lecturing; a few months later, he’s soiling himself and wandering out of the apartment. This means that Spence, unlike Bellow’s Herzog or Roth’s Kepesh, can’t tell his own story or even be an active presence in it. Instead, he is a problem that must be dealt with by other people—in particular, by Pru and his son, Arlo, from his first marriage, who are the book’s real protagonists. As they emerge from Spence’s shadow into the sunlight of Henkin’s narrative attention, the reader sees how both their lives have been shaped, for good and ill, by their intimate connection with a great man.

For Pru, as we see in the book’s opening episodes, her relationship with Spence has meant taking second place from the very beginning. When they meet, he is a young professor, and she is a graduate student hoping to study his subject, English Renaissance literature. But once they become an item, Pru realizes that “everyone looked at her differently. ‘Someone caught the big fish,’ a classmate said.” Even if she were as talented as her husband, which she doubts, Pru knows that she will never be evaluated on her own merits as long as they are in the same field. When they marry, she keeps her last name, Steiner, as a token of independence, but she knows that she has accepted the reality of subordination.

Spence and Pru are both Jewish, but they have different ideas about what that means. Spence was raised in an entirely nonobservant household and even changed his too-Jewish name: “My Christian name is Shulem,” he jokes early in their relationship. When they marry, Pru insists on bringing in a service to kasher their kitchen. But in Morningside Heights, it is easy to be and feel Jewish without practicing Judaism, and Henkin shows how Pru slowly starts to compromise:

Now, in restaurants, she would order the onion soup without asking about the ingredients, though onion soup was almost always made with beef stock. . . . One Saturday, when Spence had already left for the library, she turned the bathroom light on. She wasn’t about to pee in the dark, and she certainly wasn’t about to shower in the dark, though she’d done both those things countless times in college.

Henkin suggests that this, too, is evidence of Pru’s self-effacement, her willingness to follow her husband’s lead: “It scared her, this giving up of things, but it was exhilarating too.”

Thirty years later, however, the balance of power established at the start of the marriage is starting to reverse. Now it is Spence who is losing confidence in his professional abilities: He is under contract to write a book about Shakespeare but realizes that it is beyond his powers, leading Pru to wonder if she should write it under his name. Instead, she suddenly finds herself managing his decline, with the help of a nurse, Ginny, who becomes an increasingly central presence in their lives. Henkin shows how, in the face of disease, the value system of Morningside Heights is turned upside down. Now academic prowess and intellectual sophistication count for much less than patience, empathy, and simple physical strength. When Pru asks Ginny if she is strong enough to handle Spence, who would soon need a wheelchair, Ginny replies by asking Pru to lie down on the floor:

Pru hesitated for a moment. Then she lowered herself to the floor. She lay facedown like a dead person . . . Ginny lifted her in the air. . . . How long was Pru suspended there? Five seconds? Maybe ten? Looking back, she felt as if she’d been held aloft through the whole interview.

Henkin tells his story simply and directly, with a narrative economy that conceals much close observation and human understanding. These have always been the strengths of his work, though they are not the qualities best rewarded in contemporary American fiction, whose arbiters tend to prefer showier kinds of construction and proofs of relevance. But Morningside Heights is not very interested in social observation, and when the book moves outside the domestic realm, it tends to become imprecise. Henkin’s sketch of the career of a young programmer in Silicon Valley, for instance, is cursory in a way that suggests a fundamental lack of interest in the whole milieu.

Even in the world the novel knows best, there are details that seem a little off. As a cultural type, for instance, Spence Robin doesn’t make much sense as a product of the era in which he is supposed to have thrived, the 1980s and 1990s. In reality, the English-department celebrities of that time were figures like Stephen Greenblatt and Stanley Fish, who are not known for their monastic indifference to the world outside the ivied walls. Even the detail of Spence’s changing his name from Shulem doesn’t fit someone born in the late 1940s. (“I was trying to escape the Lower East Side,” he tells Pru, but by then most Jews already had.) In all these ways, Spence feels like a figure from an earlier time—the generation of Lionel Trilling and Meyer Schapiro, or perhaps a little later—who has been transplanted for fictional purposes into an era closer to the present.

Where Morningside Heights convinces is not in its cultural or social observations but in small human episodes—as when the rapidly declining Spence insists on going to a department store to buy Pru a birthday present, even though her birthday is months away. At first, the reader thinks this is a sign of dementia, but he explains himself to Pru quite rationally: “I don’t know if I’ll be alive on your birthday.” Sad as this is, it becomes sadder and sharper when Pru realizes that her reaction is dismay—not at the idea that Spence might be dead soon but at the possibility that he might not, dragging them both through the purgatory of his decline.

If Pru has accommodated herself to being second to Spence, at least she has the compensation of his presence and love. His son, Arlo, has neither, which makes him a much fiercer critic of both Spence and the intellectual code he lives by. Arlo’s mother is a hippieish free spirit who trundles the young boy around the country from one commune or short-term job to the next. He visits his father for only a few weeks each summer, competing with his half-sister, Sarah, for his father’s attention. As a result, Arlo—named after Arlo Guthrie, of course—grows up both estranged from Spence and obsessed with him: “He wore a New York City subway token around his neck, as a reminder of where his father lived and that he could leave whenever he wanted to,” Henkin writes.

As a young teenager, Arlo finally decides to do just that, packing a bag and descending on his father’s other family. The middle section of the novel sketches the two years he spends trying, and ultimately failing, to fit in there—a failure that has as much to do with Arlo’s self-sabotaging pride as it does with the snobbery of Morningside Heights. When he is finally diagnosed as dyslexic, it becomes clear why he has never been able to succeed at school, the only kind of success his father really values. But Arlo vacillates between wanting to please Spence and wanting revenge for years of neglect. When his father gets him a job as a bookstore clerk, he thrives at first, then deliberately gets himself fired. “He thought of another word his father had taught him, abdicate, and he started to see school, to see his whole time in New York, as a well-meaning but failed experiment,” Henkin writes.

As the novel returns to the 2000s, Henkin offers no climactic revelations, only the kind of tentative progress we experience in real life. Morningside Heights ends as it must, but the reader leaves Pru and Arlo, Sarah and Ginny each poised to go on in new, unpredictable, possibly happier directions. On the book’s last page, Pru walks up Broadway to 116th Street and feels a breeze, “a relic from last winter, a herald of winter to come”—a reminder that life is redeemed only by the fact that, for a while at least, it keeps going on.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Muddling Through

In his new book about an Upper West Side Jewish family, Joshua Henkin proves himself as a skillful writer, alternately witty and moving.

Fiction and Forgiveness

Dara Horn’s novel goes down to Egypt to guide its perplexed characters through a Joseph story.

Spanish Charity

The sight of a secular Israeli artist in a cathedral confessional in Spain is one of the more interesting moments in recent Israeli fiction. A new novel by A.B. Yehoshua.

Coming with a Lampoon

Jacobson is a world master of the art of disturbing comedy and each new work of his advances the genre—his latest one by a giant step.

Tania Tulcin

Actually, the Columbia English Department in the 1980s was indeed cloistered in its ivory tower. At the time a full-time law student at another institution while attending Columbia part-time, I was roundly put in my place by a senior professor, a prominent Melville scholar, long deceased, who scoffed at my dual endeavor and apparent predilection for combining scholarship with more worldly concerns. Had I continued in English Lit, I surely would have left Columbia for much greener intellectual pastures.