Fleishman Is a Series

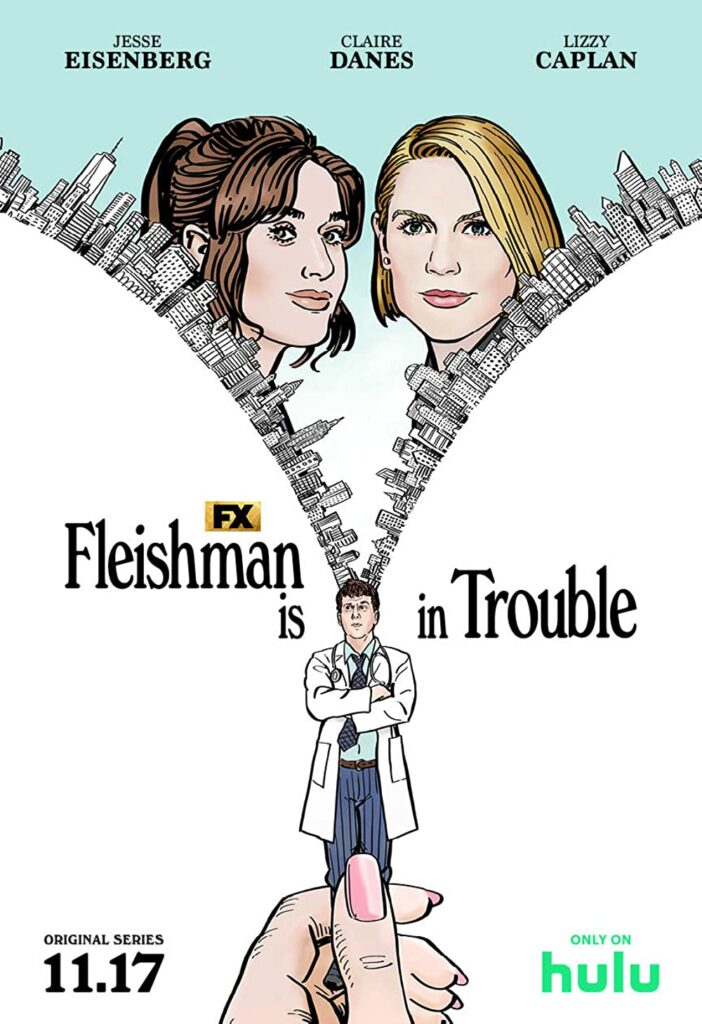

Has divorce always been this fun? Because at first Toby Fleishman is loving it, inundated as he is with messages on dating apps from women who want to date—who could believe it—him! So we find Toby (Jesse Eisenberg) at the start of Fleishman is in Trouble, FX’s new 8-episode miniseries based on the 2019 novel by Taffy Brodesser-Akner (who also serves as showrunner for the adaptation). But, as the show’s title suggests, all is not well in Fleishman’s life, and Toby’s already-acrimonious divorce from Rachel Fleishman (Claire Danes) quickly spirals into chaos when she drops their two children off at his apartment one night, only to vanish into thin air.

Toby vents his frustration into Rachel’s voicemail inbox and tries to get on with his summer plans: working at the hospital as a hepatologist and working his way through apps filled with single women. While trying not to treat his children Hannah and Solly as burdens, Toby also reconnects with his old friends Libby Epstein (Lizzy Caplan) and Seth Morris (Adam Brody), who welcome his return. Seth and Libby gladly join their voices to his anti-Rachel chorus: after all, she was the reason Toby dropped them as friends.

Toby continues with his days but he’s a ball of nerves in a way that only Jesse Eisenberg can capture. As in the novel, Toby isn’t so much stressed out by the moment, but rather perpetually wound tight. (Eisenberg delivers his lines in a clipped, highly caffeinated rhythm reminiscent of Woody Allen.)Toby’s character is certainly a stereotype—neurotic Jewish doctor—and Eisenberg plays it well. It’s an excellent performance, but also a disappointing one. Surely all the Jewish talent in the show could have come together to create a fresher take on the Jewish masculinity that it’s parodying—or a fresher take on the Jewish anything, really. In a show that has been praised for its Jewishness, the cultural and religious Jewish content is actually scant. As we follow Toby’s nervous chatter, the central concern of the show seems to be just how awful Rachel is.

According to Toby, dropping off the children, unannounced is only one of the many terrible things that Rachel has done. She’s a relentless social climber who is more devoted to her job as a talent agent than to her role as a mother and wife. Toby casts himself in sharp contrast to Rachel: he is a longsuffering husband who loves long walks and taking the subway; a true man of the people.

The battle of Fleishman vs. Fleishman plays out against the backdrop of the impossible expectations created by living on the Upper East Side, with its trophy wives, finance-bro husbands, and endlessly competitive social scene. The show was filmed on location and successfully captures the mood of the city a few years back, with visual references both iconic (pushing a stroller under a bridge in Central Park) and surprising (standing in front of the marquee for Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, an excellent, oddball 2010 Broadway musical). The setting is also realistically claustrophobic. In a city of eight million people, how the hell does Toby keep running into people he knows?

The person who appears to know him best is Libby, and her character narrates the series as she does the novel. Libby, like Brodesser-Akner herself, is a journalist, and her perspective is eerily omniscient. In the novel, Libby’s funny-sad diatribe almost single-handedly drives the book through its near-four hundred pages, leading reviewers to describe Brodesser-Akner as a kind of female Philip Roth (well, that, the well-named secular Jewish characters, and all the sex).

Libby’s dulcet tones, which are both addictive and vindictive unfortunately become a crutch in the adaptation: her voice-over highlights the excessive faithfulness of the series to its source material. Even the visual style takes its cues from the book’s cover, an upside-down image of New York City rooftops with the Empire State Building in the distance. The show opens with a flipped view of the city and takes great joy in zanily spinning us upside down whenever things in Toby’s life turn, well, upside down. And while the haunting soundtrack signaling domestic doom is new and evocative, the show otherwise seems to lack the creativity or energy to truly adapt the book for television. Of course, one can hardly blame Brodesser-Akner for wanting to preserve the voice of her wickedly smart novel, but keeping Libby’s voice comes at the cost of Toby and Rachel’s character development on the screen.

Once the present-day mess has been established, the story of Toby and Rachel’s relationship begins to unfold in a series of flashbacks that reveals their giddy days of courtship, followed by a slow turn to the brutal reality of a mismatched marriage. The flashbacks are largely accompanied by Libby’s voice-over, piped in any time our leads threaten to launch into a truly interesting scene. Several episodes contain narration for nearly—or more than—half the run time, apparently in an effort to answer the unasked question: what if large swaths of a television show were an audiobook? The best reason I can think of for this choice is that it distracts from the unconvincing attempt of Eisenberg (thirty-nine) and Danes (forty-three) to play college-aged versions of themselves. (Astonishingly, Eisenberg’s curly wig and Danes’s ratty sweatshirts do not make them look twenty-two years old.)

Ignoring the unsettling stabs at youthfulness, if we can, Eisenberg and Danes do successfully command the screen as they battle for ownership of the divorce’s narrative. In contrast to Eisenberg’s nervous energy, Danes is cold and imposing until, suddenly, she isn’t. The great revelation of the show is that what Toby and Rachel have most in common is a shared and deep self-loathing. Toby’s version of self-loathing is loud: he has a desperate desire to be loved by everyone, paired with a conviction that he is too flawed to be fully loved.

Rachel, meanwhile, hates and blames herself for a nagging sense of insecurity despite all her achievements, and for her failure as a parent no matter how hard she tries. Rachel’s tragedy is keener than Toby’s because she actually isn’t a particularly good parent, though not for the reasons she believes and not in a way which she is equipped to correct. Securing her children spots in a prestigious prep school will not make them pine any less for the parent who is never home, working to afford that prep school.

The show is littered with fights between the Fleishmans, but when Libby eventually shifts her perspective to sympathize with Rachel, those bouts are revisited and presented quite differently. While earlier Rachel berates Toby, the roles flip in the new flashbacks, with Rachel bearing the brunt of the fighting. Is Rachel truly the villain of the first six episodes, or have we been duped by an unreliable narrator? In the novel, this shift in perspective is the crux of the book, showing readers that we aren’t reading an homage to Roth, after all, but a sendup of his worst habits as a novelist, and of the characters he invented. Alexander Portnoy? Nathan Zuckerman? David Kepesh? Add Toby Fleishman to that list, but don’t sympathize with him. Through him, Brodesser-Akner asks us to wonder if we can trust anything we’ve read since Goodbye, Columbus. Oddly enough, Roth’s novel When She Was Good also involves a female protagonist who is depicted as shrill, vindictive, and grasping. Unsurprisingly, that protagonist did not receive the sort of balanced treatment from Roth that Rachel receives from Brodesser-Akner.

How does the series handle the crucial reveal of Rachel’s perspective? Well, with a lot of voice-overs played across hastily reconstructed scenes. While in the novel the extent of the reveal is shocking, here it is blatantly obvious from the first scene. It leaves the viewer less with a sense of shock and awe than with disappointment that Claire Danes’s screen time was so limited.

Fleishman Is In Trouble is a success of acting and zany camera angles, but it is ultimately a failure of adaptation. It wants to show the complex ambiguity of the Fleishman divorce but ends up telling a stark he said-she said story. It wants to maintain Brodesser-Akner’s incredible voice, but never really figures out how to do that. Instead, the series insists on faithfully hitting every single plot point of the novel, and largely in the same order.

There is a question at the heart of Brodesser-Akner’s novel: who is the bad guy, Toby or Rachel? The question is, of course, a trap for the reader—there is no hero or villain. But in the complexity and verve of Brodesser-Akner’s writing, it becomes a very tempting trap to step into. Yet on the screen, the thorniest questions from the book become as interesting as asking whether Jesse Eisenberg’s Jewfro wig makes him look twenty-two again. It doesn’t, but if Lizzy Caplan makes a full recording of the novel, I’ll be sure to take a listen.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

No Sex in the City: On Srugim

A new Israeli TV show chronicles single life in Jerusalem.

Welcome to Rehavia

Shababnikim, the hilarious Israeli sitcom that follows four ne’er-do-well yeshiva students, is back–and it has something serious to say too.

Shababshubap

Black hat chic: Shai Secunda's review of Shababnikim, the new television show about cool yeshiva students.

Getting Out from Under: The Philip Roth Story

“I don’t want you to rehabilitate me. Just make me interesting,” Philip Roth told his biographer. Has he?

Nancy Kaplan

I watched the series and was underwhelmed, to put it mildly. I did not read the book. In the final episode they played a contemporary Israeli song as Toby and his kids walked home from their shul after the bat mitzvah meeting. As the music played, the Hulu captions delivered English transliteration of the Hebrew rather than English translation of the lyrics. That was very annoying! Presumably the choice of the music had something to do with what was happening to the characters in that scene, but it was impossible to tell what that might have been. I imagine that the number of viewers who are familiar with the song and already know the words is virtually nil.