Another Round with Norman Mailer

In 1969, with typical chutzpah, Norman Mailer ran for mayor of New York City. His slogan was “No More Bullshit,” his spirit both defiant and hopeful. In Mailer’s New York, driving would be illegal, the city would secede, becoming the fifty-first state, and locals would enjoy “Sweet Sundays,” a kind of civic Sabbath without any transportation. New York would be, if not a bucolic Eden, a mellower place to feel a cool river breeze off the Hudson.

Bold, blustering Mailer baffled people. When William F. Buckley ran for mayor, he vowed to “demand a recount” if he won. Mailer wouldn’t have said that. He was dead serious—all his life, he craved respect; he wanted, above all, to be taken seriously. That was true of his novels, though his most indelible works—The Armies of the Night and The Executioner’s Song, both Pulitzer Prize winners—were essentially factual. So, in a sense, was his first novel, The Naked and the Dead, a naturalistic account of Mailer’s wartime experience in the South Pacific.

Much of Mailer’s character—wild ambition, boundless egotism, ferocious energy—went into his mayoral adventure. Like many writers who crave a purpose beyond making sentences, Mailer imagined himself a force, a macher, in the world of action. He had, he once wrote, been running for president in his head since 1949. Eventually, he would settle for president of PEN America, the writers’ free speech organization.

As it happens, wanting more from life was a major theme of Mailer’s life. From an early age, Mailer restlessly pursued fame and success beyond what any nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn might hope for. To an amazing degree, he succeeded, betting on himself with unfailing confidence. Since his death in 2007, Mailer’s star has dimmed, yet recent years have witnessed something of a Mailer revival. A new biography, Tough Guy, takes a pugilist’s approach to its subject, while several Library of America volumes canonize Mailer’s early work. On the crowded horizon are a Mailer TV series, a Yale Jewish Lives biography, and a Showtime documentary. Is Mailer, who would have turned one hundred this year, ripe for reappraisal? If nothing else, he’s enjoying quite an afterlife.

The years covered by the Library of America volumes (1945–1969) were erratically brilliant for Mailer. After several novels, Mailer turned to journalism, using alter egos—not Mailer, exactly, but not far off. These narrators chronicled everything they saw, plus the unseen—the “subterranean” hopes that comprised “the dream life of the nation.” Mailer’s subject was America, his finger on its pulse, chronicling the now.

Mailer had the gift of enlivening everything he touched, and he touched almost everything, from politics to Hollywood to sports. He was, for two decades, a literary Zelig, popping up in Dissent, Partisan Review, and Playboy. He profiled John F. Kennedy (and claimed credit for JFK’s election). He wrote about Nixon (who resembled “an undertaker’s assistant”) and Lyndon Johnson (“a well-to-do small-town mortician”). He practiced the cruelty of truth, not distortion.

That was just the literary side. Over the same period, there were four stormy marriages, several arrests, numerous drunken fights (“Why can’t I be punched by Norman Mailer?” Andy Warhol sighs in Factory Girl). He wrote a novel so fine it made Orwell blush; dabbled in marijuana, and got addicted; cofounded the Village Voice, then quit abruptly. He threw public tantrums and wept afterward. (“I have a demon in me,” he explained.) He took up boxing, as if punching his way out of his good Jewish boy role.

Between adventures, he forged a vision of life as a contest requiring heroic bravery. To Mailer, courage conferred dignity; boldness bred self-respect. He was an inveterate thinker—“The little pisherke with the big ideas,” his first mother-in-law said—who believed in living instinctively, by one’s wits. The important thing was to preserve vitality, resisting the life-draining forces and toxic conformity of 1950s America.

All of which raises an obvious question. How did Norman, son of Brooklyn, become “Norman Mailer,” self-styled outlaw? Did Mailer have a secret Jewish life? A related problem bedevils Mailer’s biographers. Namely, which Mailer? Mailer could be, depending on his mood and sobriety, sweet or harsh, gentle or violent. One can shuffle the deck almost endlessly: Radical Mailer or bourgeois Mailer? Loyal Mailer or spiteful Mailer? Sometimes, the categories blur. When Mailer first met Diana Trilling, he called her the worst thing possible. “I am usually addressed with appalling respect,” she recalled. She found him refreshingly crude.

Born in Long Branch, New Jersey, in 1923, Mailer grew up comfortably, a child of the Depression who never felt its pinch. “I came from a good Jewish home,” Mailer recalled, and so he did, sort of. Mailer’s grandparents were Lithuanian Jews; his maternal grandfather was a rabbi. When Mailer was young, the family moved to Flatbush, then Crown Heights. On Fridays, the Brooklyn Mailers lit Shabbos candles and, for the most part, kept kosher. Like many tender, watched-over children, Mailer lived in two worlds: the protected home world and the jungle of Brooklyn.

His main protector, his powerful mother, Fanny, wasn’t warm or nurturing but offered fierce devotion, the kind Freud says produces a conqueror. “My boy’s a genius,” she would declare, words her son would recall with gratitude: “Capote is wrecked now, but he didn’t have a good Jewish mother.” For Mailer, this would be crucial.

Norman’s father, Isaac, was another story: a strange man, aloof and refined, with a Yiddish British accent perhaps unique in Brooklyn. Barney, as he was known to his friends, worked as an accountant—or, rather, failed to work, relying on Fanny’s income from the family oil-delivery business. Yet Barney had a reckless streak that belied his passive exterior. While still young, Norman learned his secret: a ruinous gambling habit. While remaining devoted to his mother, it was Mailer’s burden to forgive his reckless (and feckless) father.

For all the attention he received from his mother, aunts, and younger sister, the facts of Mailer’s youth suggest a lonely childhood. At school he was timid and unathletic. Home was a formal, somewhat chilly place, though hardly calm—a friend recalled Fanny’s “perform or else” attitude (“It was all tap dancing and performing”). Luckily, the quiet, studious child was fast tracked. At P.S. 161, in Crown Heights, his IQ topped 170, the highest in school history. From there, Mailer blazed through high school, graduating at sixteen.

On to Harvard, another world, where he kept a gin bottle on his mantel (he heard Hemingway liked gin). Mailer’s core qualities—ambition and audacity—were slowly emerging. More obviously he craved approval. “I lived completely . . . in the impressions of others,” he recalled, comparing himself to a celebrity who didn’t “believe in her reality.” That emptiness, though painful, had an upside, allowing him to shift fluidly between identities. But the performance felt hollow. “To myself,” he wrote, “I was no good.”

Mailer studied engineering, but his major discovery was literature. Now reading seriously—Steinbeck, Dos Passos, Farrell—he began writing, too, first stories, one of which won Story magazine’s national award. “It’s all happening too easily,” Mailer told his parents. Engineering fell away; the first stirrings of vocation pointed Mailer toward writing. At seventeen, he declared his intention to become “a major writer.” That meant novels, the exalted form, not journalism or short stories.

His real education was the army. “I have to go fight in the war, so that I can write the great American novel,” Mailer told his wife, Beatrice. Still timid, he joined the rowdy, horse-riding 112th Cavalry Regiment, a bookish Jew among rude roughnecks. “It was like Deliverance,” Mailer recalled. “I didn’t open my mouth for six months in that outfit.” Never mind the Japanese; Mailer was more afraid of his own unit.

The army could have broken Mailer; instead, it made him. Here was the world outside Jewish Brooklyn; here was Texas, the prairie, the West. Shipped to the Philippines, he discovered America—its speech, its dreams, its prejudices. Mailer’s platoon would reunite in The Naked and the Dead, which drew extensively from Mailer’s dense and detailed letters to Beatrice.

When fame struck, Mailer was twenty-five, still callow. “Gee, I’m first on the best seller list,” he shrugged. Soon his mood darkened. For a while, celebrity was “the worst thing that could have happened.” His anonymity—so crucial to his writing and research—had vanished. The observer was now the observed.

Around now, something began to shift in Mailer. Outwardly, he was emboldened. “In social life I have a crutch, I am Norman Mailer,” he wrote in 1952. Privately, he felt “little and ugly,” afraid of strangers. Yet he still had a sense of destiny. “I, who am timid, cowardly, and wish only friendship and security, am the one who must take on the whole world.” The coward and the conqueror stood side by side.

For a while, the two sides of Mailer’s personality were roughly in balance. That soon changed. The 1950s were a period of strenuous self-creation. In 1955, as a Village Voice columnist, he declared his mission “to be actively disliked each week.” He succeeded. “This guy Mailer is a hostile, narcissistic pest,” a reader complained. “Lose him.” By then, Mailer had suffered devastating reviews of his two follow-up novels. After that, he wrote, “something broke in me. . . . I was finally open to my anger.” Shyness became boldness. Weakness became toughness. Naivete became worldliness. During the mid-1950s, “there appeared the toughie who hated the nice Jewish boy,” Alfred Kazin recalled. It was as though Mailer had erased his past: Brooklyn, family, home.

The story of a good Jewish boy’s transformation might make for a lively biography. Richard Bradford’s Tough Guy is the sixth life of Mailer and easily the harshest. When he mentions Mailer’s “career as a shifty literary narcissist,” you picture a hatchet being sharpened with Mailer’s name on it. In fact, Bradford goes further, deflating Mailer at every turn. His portrait isn’t warts and all. It’s warts and nothing else.

Ironically, Bradford borrows heavily from more sympathetic biographies. (As best I can tell, he didn’t visit any archives or conduct interviews.) Can he offer a fresh portrait, a different Mailer? Not remotely. Bradford’s Mailer is a scoundrel—“a hypocrite,” “a control freak,” “a serial fornicator.” “But let us set aside moral judgments,” he writes—as though he could. Mailer, already clownish, becomes more absurd—a caricature of a caricature.

Bradford has little to say about Brooklyn or why a smart boychik might wish to shed his Jewish skin. To be Jewish, of course, is to have a past—to not be, so to speak, the author of your own story. But Mailer needed freedom, personal and literary. He wanted to write great American novels, not a sequel to Call It Sleep.

In a 1960 letter to Diana Trilling, he gave himself the blank past he seemed to need. He had “no past to protect,” he claimed, “no emotional memory.” As he told Trilling, “being a major novelist is not a natural activity for a Jew.” Being “major” required ruthlessness. From then on, he strove to remain both ruthless and rootless. To continue writing—“to defend my gift”—he needed to be American. He could imagine if he failed: “the decline in my reputation would have gutted my liver.”

If the need to pose was obvious, so, too, were the risks. “If you posture,” Mailer wrote, “if you take on the trappings of a personality which is not altogether natural for you . . . the pose begins to become a bona-fide part of you.” Young Mailer, intensely self-aware, seemed to see his future: Eventually, the pose hardens. The mask comes to fit the face.

At times he seemed delighted to wear the mask. “If / Harry Golden / is the gentile’s / Jew / can I be / the Golden Goy?” he wrote in a poem, naming the popular Jewish humorist. Yet the good Jewish boy kept returning. “How one does one go home again,” Mailer wrote in 1952, having moved back to Brooklyn, where he faithfully attended Shabbos dinners at home. Mailer’s ambivalent dance continued through the 1960s. Mostly, he concealed. But not always.

Writers hiding their Jewishness don’t analyze Hasidic texts for Commentary, as Mailer did in 1962. “I thought, ‘We have this great Jewish tradition, and I’m alienated from it,’” he later recalled. As the story goes, Mailer pitched a column about Buber’s Hasidic tales. Skeptical, Norman Podhoretz declined, but after much hectoring, he relented, handing Mailer his column. Every other month, the Golden Goy wrote a midrashfor Commentary.

It wasn’t Mailer’s first Jewish writing. In The Naked and the Dead, we have anxious, gloomy Goldstein, who refuses to drink army beer (“What if it should poison me?”), and Roth, his Jewish-atheist counterpart, both of whom suffer the crude antisemitism of their unit. Yet Mailer insisted he wouldn’t write a Jewish novel. “Oh, Lord, there is absolutely no need,” he sometimes said.The Jews had Isaac Bashevis Singer. “There are too many good Jewish writers around,” Mailer told Martin Amis in 1991. If he couldn’t compete, he wouldn’t dabble.

At least once, however, Mailer did attempt a Jewish novel. The manuscript, never published, survives among Mailer’s papers, hidden in plain sight. Gone are the Kellys and Madisons of Mailer’s published fiction. Instead, we meet the Miriloviczes, a shtetl-bound Lithuanian family resembling the Mailers.

There is well-dressed Archie—“the strangest Jew I’ve ever seen,” says his father-in-law, noting Archie’s Yiddish British accent and elegant wardrobe. Meanwhile, his wife, Jenny, a rabbi’s daughter, prays to the Ba’al Shem Tov that her child become great. A strong but thwarted woman, she wants “a warrior” and grooms him accordingly.

Reading these lively pages, we spot another character: Norman Mailer, comic writer. “I can’t write humorously,” Mailer realized in college, yet here he is peddling classic Jewish shtick. In one scene, a boy just starting cheder is tutored by his father:

Now, listen, there was a great doctor, Moses Maimonides, not the other Moses, but Moses Maimonides, a very great rabbi.

Was he a fisherman?

Rabbis are not fishermen. I’m telling a story. Keep quiet. This Moses Maimonides was a doctor.

A relative of Dr. Goldfarb?

I don’t know. He lived a long time ago. What’s the matter? Are you nervous about going to school?

Yes.

Well, don’t be. Listen about this Moses Maimonides.

The scene ends, and so does Mailer’s Jewish novel. For decades, Mailer could neither finish nor abandon it. Sometimes he disowned it. Yet Jewishness—intolerable, incompatible, inconducive—suffuses the story.

Inevitably, Mailer’s Jewishness was overlooked. Such was Mailer’s fame in the age of the writer-celebrity that the world only saw a fraction of the complex person. That was increasingly the case as Mailer’s private life became very public and very messy.

On November 20, 1960, Mailer stabbed his wife, Adele, with a penknife, nearly killing her. It happened after a wild, chemical-fueled party at the Mailers’ apartment. Some thought Mailer had gone crazy; in fact, years of rage, heavy drinking, and violence without consequence made a disaster likely. “I insist I am sane,” Mailer said, though a psychiatrist disagreed, sending Mailer to Bellevue. He feared he would be committed. “I am a Jewish writer,” he reasoned, “and Jews just don’t do this sort of thing unless they are really crazy.”

Gradually, Mailer’s reputation recovered. Partly, this was thanks to his friends—people loved Mailer, forgave Mailer, defended Mailer, and were helplessly drawn to Mailer. His charm was as large as his ego. But he also continued writing: “the one act which gave a sense of self-importance.” For Mailer, writing was toil, challenge, and performance. Mailer’s sentences unfold like adventures, with miniature plots; once launched, they twist and tumble, yet somehow stick the landing.

Mailer wrote most of his best work as a middle-aged man between 1967 and 1979. First came The Armies of the Night, published in 1968, the height of the Vietnam War, and chronicling the antiwar march on the Pentagon. Mailer was there, on the ground, marching and worrying. Does he belong there? Among one hundred thousand pious liberals? Yet this “Nijinsky of ambivalence” is most conflicted about himself. Cold, hungover, he feels “a deep modesty,” a most unsettling feeling:

Because modesty was an old family relative, he had been born to a modest family, had been a modest boy, a modest young man, and he hated that, he loved the pride and the arrogance and the confidence and the egocentricity he had acquired over the years.

Here and elsewhere, a vexed Jewishness comes into focus. We see Mailer getting arrested. Kibitzing with Robert Lowell. Arguing with a neo-Nazi. (“Throw the first punch, baby,” Mailer smiles. “You’ll get it all.”) At one point, observing himself, he notices “the one personality he found absolutely insupportable—the nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn.” Insupportable. Yet also unavoidable: “Something in his adenoids gave it away—he had the softness of a man early accustomed to

mother-love.”

This was something new in journalism. The confessionalism. The garrulousness. Yet it wasn’t entirely subjective. “Reality is terribly important to me,” Mailer once said; “one of the vices of postmodernism is it leaches out our sense of reality.” Mailer’s “new journalism” was actually quite old-fashioned in its contract with the reader: give me your trust, and in exchange you will get my best, good-faith effort at the truth.

After Armies came Miami and the Siege of Chicago, a frontline dispatch from the Democratic and Republican nominating conventions, and, later, The Fight, an account of Muhammad Ali’s “Rumble in the Jungle” with George Foreman. It could be, page for page, Mailer’s finest book, filled with hidden resonances and vivid metaphors. Foreman, slumping, moves “slow as a man walking up a hill of pillows.” Then he’s walloped. “Down came the champion in sections.” A short book, nearly perfect, it turns boxing into a mythic fable.

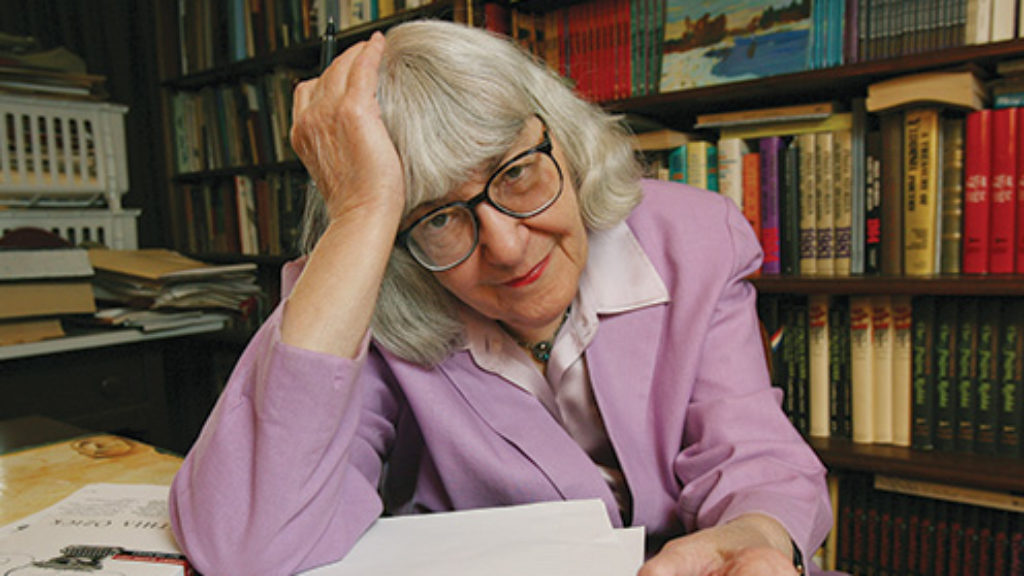

After each success, Mailer chased new risks; his favorite tightrope was live TV. What’s remembered, fairly or not, are the disasters, like his infamous flameout on The Dick Cavett Show. “Are you really all truly idiots, or is it me?” he asked the audience. “You!” they yelled. That same year, in New York, he huffed through a public debate over women’s liberation, spouting macho bluster. Some remembered Mailer’s boast that an author needed balls to write. “When you dip your balls in ink, what color ink is it?” Cynthia Ozick asked from the floor, bringing down the house. (“Ozick . . . I will cede the round to you,” Mailer answered.)

By that point, Mailer’s politics had shifted dramatically. “I’m a Jew Radical from New York,” he said in 1947. He might as well have called the FBI and offered his fingerprints. Gradually, Mailer moved rightward, learning to love the CIA, yet his chief concerns were personal, even spiritual. He hated ugly, synthetic culture—dull skyscrapers, soulless machines. Through the 1970s, Mailer railed against corporatism, technology, vanishing inner lives. “The disease of the 20th century is that politics had invaded the heart,” he wrote. How to preserve one’s humanity in an inhuman age?

This profound dread remained Mailer’s hallmark. It’s hard not to see the shadow of the Holocaust in Mailer’s life. “I’m not asking for pity,” he once said, “but every Jew alive feels his relationship to the world is somehow more tenuous than other people’s.” About the Holocaust, Mailer wrote little; like many authors, including Saul Bellow, he seemed to turn away as two-thirds of European Jewry was massacred. “Neither Barbara nor I feel very strongly about being Jews—I am neither proud nor ashamed,” he told his mother in 1944. Yet a gradual reckoning seems to have taken place.

In 1962, Mailer’s Commentary column declared that “no Messiah was brought forth from the concentration camps.” The prose is calm, the emotion subdued, yet hardly absent. “It is possible that the Jews will never recover,” he adds. More than twenty years later, that repressed emotion came roaring out. To his friend Jack Henry Abbott, then in prison for murder, he issued a scream: “Just as I don’t know what it is to be a convict, you the fuck don’t know what it is to be a Jew.” The scream continued:

You don’t know what it is to have six million of your people killed when there are only twelve million of them on earth. You don’t know the profound and fundamental stunting of existence that got into the blood cells of every Jew after Hitler had done his work.

In the mid-1970s, Mailer continued churning out books and chasing experience (“Fill the pen again!”). Despite being short, jug eared, with curly hair resembling “a sterling silver Brillo pad,” he had little trouble attracting women, many gorgeous and accomplished. Someone who marries six times is, if nothing else, an optimist, and hope regularly triumphed over experience for Mailer. “I don’t have a pattern, I have a dialectic,” he once wrote, meaning each wife was unlike the last. Mailer was, as Bradford reminds us, frequently unfaithful, though he made at least one serious stab at monogamy. “Which wife are you?” people asked Norris Church, whom Mailer met in 1975. “The last one,” she answered. And so she was.

Mailer’s risk-taking lessened but hardly vanished. In 1981, he supported the parole of Abbott, a convicted bank robber, forger, and murderer whose prison writings beguiled many New York literati. Mailer had long extolled violence; in his audacious 1957 essay, “The White Negro,” he argued that violence was curative, releasing anger, and courageous, asserting individual will. Many readers hated Mailer’s moral inversions. They recoiled again when Abbott, freshly paroled, murdered a young waiter. “Culture is worth a little risk,” Mailer insisted, unrepentant. Later, he admitted that “people who say that I have blood on my hands are right. I do.”

The Abbott affair, a sad, squalid chapter, ended a phase of Mailer’s life. In 1984, Mailer became president of PEN. (“Norman Goes Legit,” Time magazine declared.) He drank less and fought less. He even forgave his oldest frenemy, Gore Vidal. “There are two sides to Norman Mailer, and the good side has won,” Jason Epstein declared.Ambition still burned to write long, weighty novels. Ancient Evenings (1983), set in pharaonic Egypt, was the perfect vessel for Mailer’s mysticism, his yen for karma, ghosts and sprits, past lives and future lives. The book presents a map of ancient mysteries, with Mailer as hierophant. “If you read Ancient Evenings for the story, you will hang yourself,” Harold Bloom wrote. For some readers, tuned to Mailer’s special frequency, the book was an amazement. For others, not so much.

Eight years later, Mailer published Harlot’s Ghost, a long hymn to the CIA. By that point, he was no longer kneecapping fellow writers or skewering the talent in the room. “Oh, I don’t care about that anymore,” he said in 1991. “We’re an endangered species. Let them all thrive.” The older Mailer, neither enfante nor terrible, could seem surprisingly Zen. “I’m at peace with myself in a way that I wasn’t for many, many years,” he said. “I feel more sane than I’ve ever felt in my life.”

Of Mailer’s forty-something books, which will last? One can forget mystical Mailer, ignore essayist Mailer, take or leave novelist Mailer. What’s left? Primarily, journalist Mailer, a world-class observer and chronicler. Mailer’s curiosity, his passion and detachment, most of all, his amazing alertness to mood and atmosphere, made him a born reporter. The irony, of course, is that Mailer didn’t really respect journalism. Only the novel.

As for Mailer himself, he remains fundamentally puzzling. What produced such towering rage? The pressure of pretending? The harsh reviews? (“Mother never told us how to cope with people who don’t love us,” Mailer’s sister said.) Often, Mailer seemed to yearn for a world that doesn’t exist, a world of beauty and Sweet Sundays, though one senses that no amount of beauty—or praise, or power—would have satisfied him. As Gore Vidal observed of Mailer, “Nothing is quite enough: art, sex, politics, drugs, god, mind.” His needs were bottomless, his expectations grandiose.

Yet Mailer could be immensely generous and loyal, even to strangers. “Dear Salman Rushdie,” he wrote the author of The Satanic Verses, offering hope, humor, and solidarity after the fatwa. When young authors wrote Mailer letters, he replied, blessing their ambitions. These are not the actions of a selfish scoundrel, though any moral accounting is tricky. What Mailer lacked, it seems, wasn’t generosity but compassionate sympathy; the pain of others seemed not to register with him. His life seems free of moral striving—a form of courage he didn’t value.

Today, Mailer seems passé, one of the great literary narcissists now blessedly gone. “Why is Norman Mailer still famous?” Terry Teachout once complained. Yet the pendulum may be swinging back in Mailer’s direction. In a cautious, career-minded era, Mailer’s risk-taking feels like a tonic. Likewise his refusal to feign virtue or modesty (easier, perhaps, since his vanity was never connected to his goodness). Mailer seems fundamentally sincere, even his wildest performances. There he was. For better or worse.

Or, perhaps, there he wasn’t. “I don’t believe anyone has ever understood my relation to being a Jew,” he wrote in 1985. Nor would he assist them. “It’s very hard to explain, and it goes very deep.” Surely it would have surprised people that Mailer owned Graetz’s History of the Jews and a full twenty-six-volume set of the Soncino Talmud (“It has influenced everything I have written”). When Mailer read Born to Kvetch, he caught fire. “If you really want to understand me, read this book!” he told his wife.

In 2007, as death loomed, Mailer was asked what role Jewishness played in his writing. “An enormous role,” he replied, praising the Jewish role in history: “We’re here to do all sorts of outrageous thinking.” Mailer’s Jewishness, however vague, fraught, or concealed it had once been, was now simpler, a source of pride. “I’m in no way a formal Jew,” he said, “but in every way I consider myself Jewish.”

With Mailer, no final accounting seems possible; he’s too prolific, too protean. Inevitably, his biographers give us a tragic Mailer, trapped by fame, seldom content, unable to be himself. But also a courageous Mailer, fiercely alive, gloriously free. We see a fragile Mailer, unable to tolerate feelings of shame, self-loathing, and anger. And an enviably heedless, shameless Mailer, whose adventurous life makes others look small and cautious.

Sampling Mailer’s biographies feels like reading a mythical fable: a creature of vast energy and ambition, a great, unchained life force. “I’m a catalyst—I set loose forces,” Mailer once said. “If I’m not right, I’ll set loose terrible forces.” Such amazing creativity. Such awesome destruction. What a spectacle. Impossible to ignore.

Suggested Reading

People of the Book World

"The Jewish market has become quite a good one,” a Knopf editor observed; even the “goy polloi” were buying, wrote another staffer.

Cynthia Ozick: Or, Immortality

Ozick is as marvelously demanding, harrumphing, and uncompromising as she has always been.

Journeys Without End

For some three decades Lionel and Diana Trilling shared a limelight that was not quite identical but never entirely separate.

A Stone for His Slingshot

In 1948 screenwriter Ben Hecht lectured “a thousand bookies, ex-prize fighters, gamblers, jockeys, touts,” and gangsters on the burdens and responsibilities of Jewish history. The night at Slapsy Maxie’s was a big success, but the speech was lost, until now.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In