Cynthia Ozick: Or, Immortality

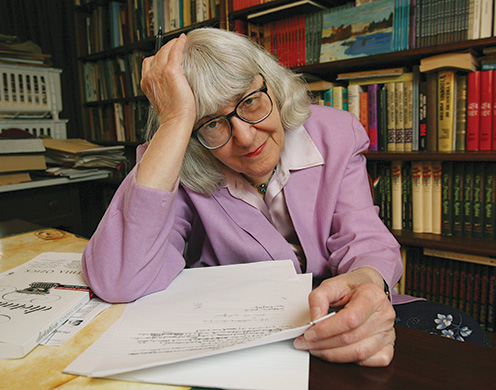

Why does Cynthia Ozick, at 88 an undisputed giant of American letters, still seem obsessed with fame?

Like nearly everyone else who appreciates Cynthia Ozick’s brand of genius—and I don’t mean “brand” in the 21st-century sense, but rather the brand plucked from the fire, searing one’s lips into prophecy (the distinction between the two neatly encapsulates Ozick’s chief artistic fascinations)—I’m not the type of person who is a fan of anything at all. As something close to Ozick’s ideal reader, I am skeptical of the entire concept of fandom, religiously suspicious of the kind of artistic seduction that would make one uncritical of anything created by someone who isn’t God. But I am nevertheless a fan of Ozick’s, in the truly fanatical sense. I have read every word she’s ever published, taught her fiction and essays at various universities, reviewed her books for numerous publications (occasionally even the same book twice), written her fan letters and then swooned over the succinct handwritten replies in which she graciously gave me a sentence more than the time of day, and even based my own work as a novelist on her concept of American Jewish literature as a liturgical or midrashic enterprise (a stance she has since rejected, though too late for me). As a young reader I was astonished by what she apparently invented: fiction in English that dealt profoundly not with Judaism as an “identity,” but with the actual content of Jewish thought, at a time when almost no one, and certainly no one that talented, was quite bothering to try.

Today I remain utterly seduced by the dazzling architecture of her stories, the distilled clarity of her sentences, and the urgency of her arguments. But my love for her is haunted by one point of strange discomfort: her obsession with fame, which in one form or another suffuses nearly everything she writes. (In this collection she loudly clarifies that she really means “recognition,” since “Fame is fickle”—but we knew that. Fine, then: high-end, enduring fame.) Her early masterpiece, “Envy: Or, Yiddish in America,” is a novella-à-clef about Isaac Bashevis Singer’s cheap glamour overshadowing better-yet-untranslated writers; her novella “Usurpation (Other People’s Stories)” involves, among much else, a fable about a magic crown that grants its wearer eternal literary fame (spoiler: this isn’t a good thing); The Messiah of Stockholm is about the forgotten genius Bruno Schulz and failed writers and charlatans vying to steal his legacy; Heir to the Glimmering World includes a scholar and a scientist both robbed of their greatest discoveries, forced to become wards of a famous-yet-thoughtless millionaire . . . I could go on, but instead I will simply point out what Ozick’s entire oeuvre brilliantly enacts: Despite the underlying assumption of Western civilization that we owe our world to the genius of Great Men (yes, men) whose names still resonate today, the truth is that merit and credit are only rarely linked. This sad truth is genuinely fascinating, because it unearths our most buried questions about the purpose of living as mortals in a world that outlasts us. But it also can become a perverse obsession for creative artists of every stature, because, as conventional wisdom and the degrading experience of reading Amazon reviews suggests, nothing good comes of it. Or does it?

The thought that this obsession with fame (or “recognition”) would still affect someone as titanically accomplished as Ozick is, on its surface, dismaying in the extreme. But Ozick’s interest in this subject has always been civilizational rather than personal. And as her newest book, Critics, Monsters, Fanatics, & Other Literary Essays, makes clear, Ozick’s tendency to run a live wire of envy through her work doesn’t play the same role now as it did earlier in her career. Forty years ago, Ozick’s writing—both her fiction and her essays—was deeply Jewish, less because of its subject matter (though yes, that too) than because of its loud claim that art itself was a form of idolatry and fame even more so. This prizefight between imagination and obligation—once labeled by Matthew Arnold as Hellenism and Hebraism—was a fight worth having in 20th-century American culture, where art and literature really did occupy a quasi-sacred public space, a time, as Ozick recalls, “when the publication of a serious literary novel was an exuberant communal event.” But through her career-long evolution as an artist and the simultaneous coarsening of American intellectual life (about which more, shortly), Ozick’s fame-obsession has shifted, taking root once more in a Judaic paradigm, but a different one: the Jewish historical consciousness that gives the lie to American culture’s vain worship of the new.

In this latest essay collection, Ozick is as marvelously demanding, harrumphing, and uncompromising as she has always been; her curmudgeonly persona is by now so familiar that one imagines that she has been 88 for her entire life. But this collection, mostly composed of previously published essays that together take on an almost narrative trajectory, nonetheless feels different. Gone is the bitter bite of envy that once flavored her every public word, whether on behalf of her characters, the wronged or underappreciated authors she ingeniously lauded, or rarely (in the occasional autobiographical essay or interview) herself. In its place is a wonderment at the ravages of time, but also an awestruck awareness of what one gains when one is doubly blessed with both a long career and that profound historical consciousness: a rare and vivid vision of what lasts, and why.

“One of the several advantages of living long,” Ozick discloses, “is the chance to witness the trajectory of other lives, especially literary lives; to observe the whole, as a biographer might; or even, now and then, to reflect on fame with the dispassion of the biblical Koheleth, for whom all eminences are finally diminished.” Lest we think she is being metaphoric, in an essay aptly titled “The Lastingness of Saul Bellow,” Ozick fires off a sustained and gleeful volley at what amounts to the last 60 years of American letters, punishing and brilliant:

Consider: who at this hour (apart from some professorial specialist currying his “field”) is reading Mary McCarthy, James T. Farrell, John Berryman, Allan Bloom, Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Edmund Wilson, Anne Sexton, Alice Adams, Robert Lowell, Grace Paley, Owen Barfield, Stanley Elkin, Robert Penn Warren, Norman Mailer, Leslie Fiedler, R.P. Blackmur, Paul Goodman, Susan Sontag, Lillian Hellman, John Crowe Ransom, Stephen Spender, Daniel Fuchs, Hugh Kenner, Seymour Krim, J.F. Powers, Allen Ginsberg, Philip Rahv, Jack Richardson, John Auerbach, Harvey Swados—or Trilling himself?

These names, Ozick explains, are not merely dead writers whose stars have faded. They are all people with whom Saul Bellow exchanged letters, the point being that only Bellow himself remains immortal.

Ozick goes on to analyze, or try to, why Bellow’s work endures. She credits not only his sentences, but something much larger: his context, his wrestling with his own century, and that “He was serious in invoking whatever particle of eternity he meant by soul, that old, old inkling he was fearless in calling up from contemporary disgrace.” Yet contemporary disgrace, as Ozick slyly intends, is what haunts the reader here: not Bellow, but that goddamn list. At less than half Ozick’s age, and in a “field” that makes me more familiar with these names than most, I read that list with a faint feeling of awe, as though beholding the ruined Ozymandias. And that list is merely the most sustained version of Ozick’s invocation of oblivion; it reappears in abridged form as a kind of Greek chorus throughout this book. “As for poor befuddled mystical Jack Kerouac and declamatory fiddle-strumming mystical Allen Ginsberg [him again], both are diminished to Documents of an Era: the stale turf of social historians.” Tillie Olsen, renowned for her 1960s feminist stories, was “rewarded afterward with close to five decades of personal freedom, affectionate celebrity, and public honors . . . and never again sat down to write anew. She lived to ninety-four.” Of Edmund Wilson (him again), Ozick mourns, in poignant italics, “he is not read.” Nor, Ozick reminds us, are canonical authors spared this curse: “[A]part from Orwell specialists, who now reads The Road to Wigan Pier?”

There is, of course, a fair retort to this litany: Works need not be read in perpetuity to have branded the worlds of their readers, or for the works that follow them to be indebted to their fleeting presence—and in any case immortality is a fool’s errand. Allegra Goodman, one of the select contemporary novelists Ozick has publicly praised, once enacted this argument in an imagined dialogue:

“Well,” your inner critic counters gloomily, “just remember that when you’re gone, your books will suffer the same fate as all the rest. They’ll be relics at best. More likely, they’ll just languish in obscurity.” To which I have to say: So what? I won’t be around to care.

Yet Ozick is very much around to care, and she will have none of this. She is singularly, almost maniacally, devoted to literature, and she is not merely merciless but prophetically searing in her surprising diagnosis of what ails literature today. In the gauntlet-strewn essay that opens the volume, “The Boys in the Alley, the Disappearing Readers, and the Novel’s Ghostly Twin,” she begins with Jonathan Franzen’s whine about how few people read “serious” literature and the experimental novelist Ben Marcus’s whine about how few people read “difficult” literature before she points out the stupidity of it all. The real problem is that, as she puts it, “the readers are going away.” A less astute critic (that is, nearly everyone else) would blame TV and the internet and call it a day. Instead, she offers this:

The real trouble lies not in what is happening, but in what is not happening. What is not happening is literary criticism . . . Novels, however they may manifest themselves, will never be lacking. What is missing is a powerfully persuasive, and pervasive, intuition for how they are connected, what they portend in the aggregate, how they comprise and color an era.

At first, this seems impossible. Can a lack of criticism really be the problem in an age like ours, when everyone’s opinions are endlessly and aggressively “shared”? But wait: Ozick is already on the warpath. She has the expected snobbish words for book club boosters, crowd-pleasing publishers, and Amazon reviewers, several of whom have taken to her book’s Amazon page in their own surprisingly thoughtful defense. But then she delineates what truly distinguishes criticism from mere reviews: “[T]he critic must summon what the reviewer cannot: horizonless freedoms, multiple histories, multiple libraries, multiple metaphysics and intuitions.” This, we now see, is not scolding. It is context, a reminder that “no novel is an island,” which would give thoughtful people the reasons they need to read them, to join the civilizational continuum of the imagination which still exists and always has, but is only apparent when “criticism has taught us how to see it.” Or as Ozick succinctly puts it in the volume’s preface: “Without the critics, incoherence.”

It is a relief, then, that this volume, though strewn with ruins, is also overflowing with living, breathing critics whom Ozick ushers into her own contemporary pantheon, with occasional asterisks. Among them are Harold Bloom, Leon Wieseltier, Adam Kirsch, Daniel Mendelsohn, and James Wood—along with the Hebrew scholars Robert Alter and Alan Mintz, in a delirious essay presenting Mintz’s work on American Hebrew poets, a tiny coterie of readerless fanatics (one of whom was Ozick’s uncle). In critiquing the critics, as in an essay about her longtime antagonist Harold Bloom, she even dares to ask whether a critic’s work can itself be inspired rhapsodically—or, if you will, Hellenically rather than Hebraically. (Spoiler: no.)

But in most of this volume the chief operating critic is Ozick herself, applying her uncompromising standards to the likes of Auden, Kafka, and others. These essays are sheer intellectual thrill rides. They have narrative arcs, settings (Kafka’s insurance office, Trilling and Whittaker Chambers at Columbia College, Auden at the 92nd Street Y), and best of all, characters—not merely the authors, but also the biographers and critics who shape our visions of these authors, along with, occasionally, a younger and more awestruck Ozick herself. In these, she is pervasive, and persuasive, in the credo that has emerged throughout her career: against idolatry, yes, but also in favor of the particular, context, rootedness, the profound archaeological wells from which no writer can be removed without removing his or her greatest powers.

For Ozick herself, that archaeological well is not only Anglo-American literature, but the far deeper well of Judaism. While she doesn’t quite spell it out here, Ozick’s idea of criticism being essential to literature is itself a claim with its oldest roots in Torah study. In a passage in Deuteronomy that directly denies the rhapsodic or incantatory power of scripture, Moses informs the Israelites that the Torah “is not in heaven…neither is it beyond the sea…No, the thing is very close to you, in your mouth and in your heart.” The rabbis later understood this passage to mean that interpreting Torah was itself an indispensable component of Torah, that God—or a Hellenic-style muse—is not going to show up and provide an answer to the text’s many questions. Therefore, careful readers are obligated to not merely read, but consider, compare, situate, interpret. In other words: without the critics, incoherence.

And this brings us to the central Jewish idea that drives this book, along with so much else Cynthia Ozick has given us, which at last explains her enduring fascination with fame: Without critical reading, no eternal life. The blessings recited at public Torah readings announce that the book itself, rather than some mystical promise, is “eternal life planted in our midst,” the Tree of Life that had been walled off in Eden returned to us—not God, a prophet or an artist, but a book. As Ozick admits here in an essay that is less argument than dream, “[W]riters are hidden beings. You have never met one.” The fact that Ozick’s reputation is likely to outlast most of those names on her own long lists of the dead is, in the end, beside the point. What Ozick has sought all along, it turns out—not for herself but for literature, not for writers but for readers—is not fame, not “recognition,” not even really “lastingness,” but an assurance of ongoing purpose and meaning, something perhaps better described as redemption. In the grand arc of her career, itself a gift to every writer and reader fortunate enough to encounter her endlessly demanding words, she has achieved it.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

“A Story of Commitment, Solidarity, Love Even”

Retracing her father’s wartime journey from Poland, across the USSR, through Iran and eventually to Palestine, Michal Dekel learns a lot about what it means to belong to a people.

No Joke

Sigmund Freud loved Jewish jokes and for many years collected material for the study that would appear in 1905 as Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. An excerpt from Ruth Wisse's new book No Joke: Making Jewish Humor.

Melting Pot

Joan Nathan's search for Jewish cooking in France yields some surprising results.

Her Own Creation and Pure Luck

The fraught project of becoming an American pulses through Susan Rubin Suleiman’s memoir, along with the similarly fraught project of becoming an adult.

fmoreau

An excellent and fascinating article. I absolutely agree that poorly framed criticism is at the heart of the problem. But I think it goes deeper than that. When I was young (I'm 61), it was common currency that educated people "ought" to read serious literature (and go to art galleries, and listen to classical music..), and so they did. But that's no longer true. Relativism and its various malign offshoots has done for "the canon". So my nephew, 30 years younger than me, who was studying English Literature at the time, told me aggressively that only elitist old people thought that some kinds of books (ie, literary books) were better than others.

Ultimately, people read these books because they believed in something called Western Civilization. Do the young any longer believe in it? And if they don't, why would we expect a critical tradition rooted in that civilization to survive?

One other point, though: it's premature to think that Ozick's list of the no-longer-read is the last word on this. History tells us that writers (even Shakespeare, for example) are frequently dismissed and forgotten in the immediate aftermath of their death, only to be revived later. Blame the wheel of fashion, which will turn again, at least for some.

And one more point: you're surely wrong to think that Kerouac and On The Road are already in the dustbin of history. I read it three years ago and was blown away by it. I note that it's described on Amazon has a "best seller", and has over 1,400 reviews...

Joel Drucker

Wonderful article -- elegant and informative. It makes want to read both more of Horn and Ozick. But please, tell me, what kind of powers does Cynthia Ozick have that she can determine anyone else's reading habits? Care to make a case for Bellow's significance? Go ahead, cite his ideas and the joy in reading his works. But to do so at the expense of others is petty and ill-informed.

gwhepner

WHO NOW READS GEORGE ORWELL

Apart from Orwell specialists, who

now reads The Road to Wigan Pier?

The answer surely is, “Less than the few

to whom his masterpiece is dear,

but even those for whom it's not,

and who in nineteen eighty-four

would also not have thought a lot

about the progress Orwell would deplore

prophetically, are now aware

that we're all by Big Brother watched,

but do not about this much care,

because our planet has been blotched

by something he did not predict,

islamic terror which has changed

the climate so dramatically

that all norms have become deranged.

The question asked socratically

in the first lines of this verse

does not require a reply,

for everything will be far worse

that what he chose to prophesy,.

The road to Wigan Pier was paved

with good intentions, but from hell

there's little hope that we'll be saved,

and Orwell never tolled this bell,

and yet, of course he is immortal,

because in Nineteen Eighty-Four he showed

the world that it was at the portal

of hell to which we're on the road.

[email protected]