Leapsniffing through the Vimveil: Avram Davidson’s Fantastic Fiction

Some days are goslin days. At least that’s the conceit of “Goslin Day,” a 1970 horror story by the fantasy and science fiction writer Avram Davidson, who would have been one hundred in 2023. Solomon Faroly awakens one morning to a “hotsticky feeling in the air, the swimmy looks in the dusty corners of windows, mirrors; something a tension, here a twitch and there a twitch. Notgood notgood. In short: a goslin day.” Goslins—an uncommon transliteration of the Yiddish and Hebrew word gazlan, which means “robber”—we learn, are changelings and body snatchers.

Faroly, rightfully concerned about his family, goes to “Crown Heights to consult the kabbalist, Kaplánovics.” But the kabbalist is unconvinced that anything is amiss:

“I have been through everything three times, twice. The NY Times, the Morgen Dzshornal, I. F. Stone, Dow-Jones, the Daph-Yomi, your name-Text, the weather report, Psalm of the Day. Everything is worked out, by numerology, analogy, gematria, noutricon, anagrams, allegory, procession and precession. So.

“Of course today as any everyday we must await the coming of the Messiah: ‘await’—expect? today? not today. Today he wouldn’t come. Considerations for atmospheric changes, or changes for atmospheric conditions, not-bad. Not-bad. Someone gives you an offer for a good airconditioner, cheap, you could think about it. Read seven capitals of psalms between afternoon and evening prayers.”

Kaplánovics rambles on like this, oblivious to the danger:

The foul air grew fouler, thicker, hotter, tenser, muggier, murkier: and the goslins, smelling it from afar, came leapsniffing through the vimveil to nimblesnitch, torment, buffet, burden, uglylook, poke, makestumble, maltreat, and quickshmiggy back again to gezzle guzzle goslinland.

When he goes downstairs, Faroly meets “a boy in a green and white skullcap, knotted crispadin coming up from inside under his shirt to dangle over his pants.” He asks the boy what he learned at school:

The boy stopped twisting one of his stroobley earlocks, and turned up his phlegm-green eyes. “Three things take a man out of this world,” he yawned. “Drinking in the morning, napping in the noon, and putting a girl on a winebarrel to find out if she’s a virgin.”

Recognizing this as a perverse mashup of a Mishnah in Avot (3:10) and a talmudic discussion about determining virginity in Yevamot 60b, Faroly realizes that he is speaking with a goslin. “Goslin Day” is a Jewish jabberwocky teetering on the brink of nonsense that nonetheless sends shivers down one’s spine. No one but Avram Davidson could have written it.

Adolph Abram Davidson—who went by Avram from a young age—was born in Yonkers, New York, in 1923, but he didn’t stay there, flitting from New York to Israel to Mexico, Belize, San Francisco, and Washington State, among other places, during his topsy-turvy life.

Despite his penchant for rabbinic allusions and his bushy black beard, Davidson was no rabbi. In fact, he never received a degree of any sort, though he attended New York University for two years and later took a short story writing class at Yeshiva University (where he was classmates with Chaim Potok). Yet he knew the Talmud well enough and quite a bit about seemingly everything else. He was a scrupulously observant Orthodox Jew for much of his adult life, until he became just as zealous a practitioner of Tenrikyo, a Japanese religion that many of his former coreligionists would have considered idolatry. In short, Davidson’s life story was full of the kind of misdirection and obfuscation his stories routinely spring on their readers.

He wrote science fiction, fantasy, and mystery, churning out more than two hundred short stories and nineteen novels of uneven quality. He won the Hugo Award, science fiction’s most prestigious medal, for “Or All the Seas with Oysters,” a short story heralded for what the critic Guy Davenport called “its crazily plausible concept that safety pins are the pupae and coat hangers the larvae of bicycles.” Davidson’s best tales, like “Goslin Day” and “Or All the Seas with Oysters,” emerge from forgotten or invented corners of our own world and blend fact and fiction in ways that are hard to disentangle. At the same time, much of his oeuvre is unremarkable: pulp mysteries that turn on a small revelation in the penultimate line and novels that tend to meander, weighed down by his learned antiquarian digressions.

Despite these contradictions—or perhaps in part because of them—Davidson, who was never well known to any but devoted science fiction fans, still has a small but fervent following. In the thirty years since his passing, his work has been steadily lauded and republished. The Avram Davidson Treasury from 1998, edited by Robert Silverberg and Avram’s ex-wife, Grania Davis, collected much of Davidson’s best short fiction, including “Goslin Day,” and included tributes to Davidson from more than two dozen science fiction luminaries. In his contribution, Ray Bradbury remarks that Davidson would not be ashamed in the company of Rudyard Kipling, Saki, John Collier, and G. K. Chesterton, calling him “a maker of gyroscopes that by their very logic of manufacture shouldn’t work but—lo! there above the abyss they do spin and hum.” Ursula K. Le Guin lauded “Avram’s ear for weird ways of talking,” and Peter S. Beagle wrote that “when it comes to pure sensitivity to the human use of words, the man has few peers and no equals.”

The Avram Davidson Treasury, which was glowingly reviewed by Michael Dirda in the Washington Post, was the first of several posthumous collections. Among the others is Everybody Has Somebody in Heaven: Essential Jewish Tales of the Spirit (edited by Jack Dann and Grania Davis), which collects Davidson’s Jewish-themed work and contains a biographical essay by Eileen Gunn that I’ve relied on extensively. In 2023, Davidson’s godson Seth Davis published AD 100: 100 Years of Avram Davidson, which collects one hundred of his unpublished or uncollected stories in two volumes, on the occasion of what would have been his centenary. (Seth Davis also runs a monthly podcast on Davidson, the Avram Davidson Universe.) What ought we make of this brilliant, ornery, and conflicted Jewish writer?

Davidson, who was the only Orthodox Jewish science fiction and fantasy writer of his time, had been drawn to traditional Judaism as a teenager. By the time he entered the US Army during World War II as a medic, he was scrupulously observant and tried hard to keep kosher in the Pacific theater. Later, when he was first married, he once insisted on walking all the way from the Upper West Side to the Lower East Side on Shabbat and forbade his host from turning on the bathroom light for Grania. When they moved to a community of science fiction writers in the Poconos in 1962, Grania used the local river as a mikvah in the dead of winter. The next year, they moved again, to Amecameca, a town in Mexico eight thousand feet high on the slopes of a volcano, and Avram would drive all the way to Mexico City to buy kosher meat.

Davidson’s earliest work was unambiguously Jewish. The first story in the new AD 100 collection, “Benny, Bluma, and the Solid Gold Wedding Ring,” from the mid-1940s, is a moralizing tale of a Jewish immigrant who unwittingly buys his bride a fake ring, with a magical O. Henry twist: after years of faithful marriage, the ring transforms into solid gold.

After World War II, Davidson contributed to Jewish Life, the magazine of the Orthodox Union, weaving tales around his experiences as a medic in World War II and in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence. He also wrote about his attempt to become a shepherd in Israel in the early 1950s (he had taken classes in animal husbandry in California).

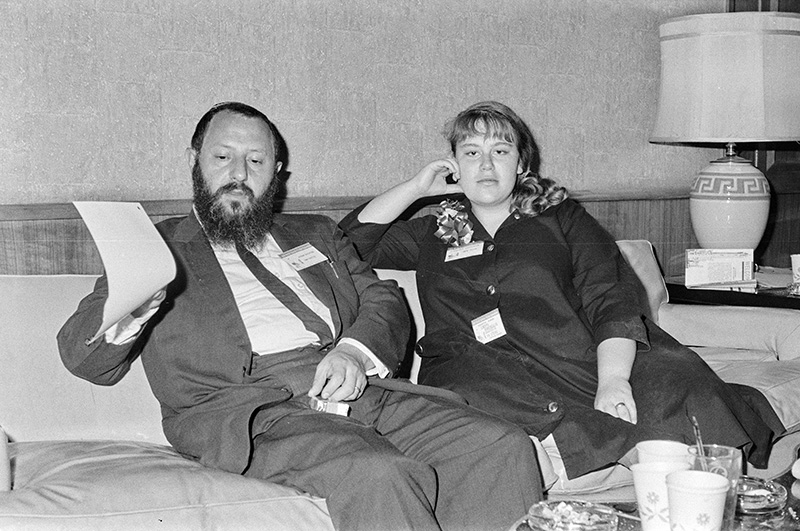

Avram Davidson and Grania Davis in 1962, Chicon, Illinois. (UC Riverside, Library, Special Collections and University Archives.)

Later, he composed a semifictitious sketch of an army chaplain who styled himself a spiritual adviser but had no interest in helping his soldiers daven. The article drew an angry rebuke from Rabbi Emanuel Rackman, then the president of the Association of Jewish Chaplains of the Armed Forces of the United States (and later president of Bar-Ilan University in Israel). Rackman called Davidson’s article “Loshon Harah” and a “caricature,” but Davidson punched right back, supplying the names of chaplains who “did the things described in the story—and worse.” He concluded bitterly, “a few cans of kosher meat, a mutilated siddur, and a plastic watchfob mezuzah are no substitute for the Taryag [613] Mitzvoth.”

Such angry zeal was characteristic of Davidson’s writing in these years. His 1957 preview of the Jewish Publication Society’s forthcoming translation of the Torah for Jewish Life was biting. He accused the work of not “being prepared on the Torah’s terms” and questioned the legitimacy of relying on a translation prepared by non-Orthodox scholars who departed from the Masoretic text in light of archaeological discoveries.

In another short story (collected in Everybody Has Somebody in Heaven), Davidson imagines a cantor at a non-Orthodox synagogue who had the gall to not only fast on Yom Kippur but to wonder, for the first time, “These hymns, these prayers, these declarations of belief in the might and power of God . . . and of the Day of Judgement—what if they should all be true?” The possibility that reality might exceed the expectations of realism animates almost all of Davidson’s best fiction.

In 1954, Davidson broke out into the science fiction and fantasy pulps. A few of his early stories still concerned Jewish themes or Jewish characters. “The Golem,” one of his best known, tells of a golem intent on destroying humanity, who—after a blow to the head and the scratching of four new Hebrew letters on his forehead—is instead put to work mowing the lawn for an elderly Jewish couple in Los Angeles.

“Help! I Am Dr. Morris Goldpepper” is about a Jewish dentist abducted by toothless aliens who need help. Far away and at his wit’s end, Dr. Goldpepper writes a secret message to the only people to whom he can turn, the American Dental Association:

Dentists and Dental Prostheticians! Beware of men with blue mouths and horny, edentulous ridges! Do not be deceived by flattery and false promises! Remember the fate of that most miserable of men, Morris Goldpepper, D.D.S., and, in his horrible predicament, help, oh, help him!

But Davidson quickly moved beyond Jewish characters and lore. Among the gems collected in Treasury are tales of New York City’s fashion designers and admen, a Southern slave owner hoisted by his own petard, and a man who thinks he’s an ancient god but is really confined to a goldfish bowl. His vast imaginarium also includes romps through the Triune Monarchy of Scythia-Pannonia-Transbalkania with Dr. Engelbert Eszterhazy and travels with Jack Limekiller through the fictional realm of British Hidalgo. In “Sacheverell,” the reader is left wondering whether the protagonist is a man who thinks he is an ape or an ape who thinks he is a man. In such stories, the reader stumbles through the obscure ambience of Davidson’s set pieces and is rewarded at the conclusion—albeit sometimes with just another mystery.

Treasury demonstrates Davidson’s versatility—even his brilliance. He was certainly a more gifted writer than many of his science fiction peers. Isaac Asimov, for example, focused on plot and galactic empires at the expense of character and setting. Davidson, by contrast, was a master of the nearly normal; he reveled in vivid settings and the thick dialects of the down-and-out citizens of small towns living on the edge of myth. In Davidson there is often just a thin veneer of the fantastic: one is more likely to meet an alien at a seaman’s lodging house in nineteenth-century London than on a spaceship centuries hence.

Yet the unevenness of Davidson’s writing is quickly apparent when one compares the carefully curated Treasury to the recent AD 100 collection. Typical of the crop of stories republished in the new volumes is “Big Sam,” a 1970 mystery about a woman who marries a man who just eats and eats all summer, working less and less and sleeping more and more until she realizes that he hibernates for the winter. In his introduction, even Seth Davis warns the reader, “If you have never read an Avram Davidson story put this book down immediately and buy a copy of The Avram Davidson Treasury. Start there.” Still, several of the tales in AD 100 are genuinely enjoyable, including “The Captain M. Caper,” about an unassuming writer who gets mixed up with the mob after contracting to write a biography of the boss.

Davidson’s best short stories are far better than his novels, but many consider The Phoenix and the Mirror his best. It takes place in a fanciful version of the Roman Empire drawn from medieval legends. Vergil, based on the poet Virgil, is a magus who must make a “major speculum”—that is, a mirror—out of virgin copper and tin in exchange for his manhood, which is magically being held captive by a noblewoman.

The novel has a number of biblical and Jewish references, including a charming digression on the meaning of the word nachash, which Vergil rightly notes can mean “snake,” “copper,” or even “magic.” But the plot is weighed down by Davidson’s research, preserved in twenty-five notebooks. Overwrought descriptions of Vergil’s hometown of Naples and his travels to Cyprus read like an exotic travelogue. The alchemical making of the mirror, which consumes nearly thirty pages of the two-hundred-page book, contains one over-the-top elucidation after another, such as the following:

I did not use ordinary water, all corrupted with gross earths and impure salts and what-have-you, no. Instead, I procured a three-year-old goat and tied it up indoors for three days without food. On the fourth I gave it fern to eat and nothing else for two days. Then I enclosed it in a cask perforated underneath and under the holes I placed a separate water-tight container and for two days and three nights I collected its urine. With this same water I also tempered all the tools of steel and iron.

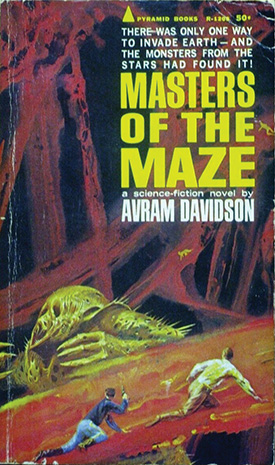

A reviewer of another Davidson novel from the 1960s, Masters of the Maze, remarked that it “wafts of the incense of scholarship for its own sake.” He meant it as a compliment, but one might beg to differ.

In 1962, Davidson made a life-changing discovery in the San Francisco Public Library when he picked up a book about Tenrikyo, a nineteenth-century Japanese religion influenced by Buddhism and Shintoism. Tenrikyo, which today has more than two million followers worldwide, focuses on selfless joyous living by helping people sweep away the “mental dust” of negative thoughts. Although Davidson continued to adhere to Jewish law throughout the 1960s, he may have already been toying with a new religious identity. A 1965 story, “The House the Blakeneys Built,” includes a family with a curious blend of Jewish and Japanese names: Robert, Shulamith, Ezra, and Mikicho Hayakawa.

Davidson’s conversion moment came in 1970. After surgery, he was visited by both a sympathetic Tenrikyo practitioner and an indifferent rabbi, who puffed on his cigar throughout the visit. Davidson quickly took to Tenrikyo with some of the same zeal that characterized his earlier Orthodoxy. He made a pilgrimage to the religion’s headquarters in Tenri, Japan, with his son Ethan in the mid-1970s. Following Tenrikyo practice, he set up an altar in his home for the spirit of his mother and another friend.

Yet even after his turn to Tenrikyo, Davidson didn’t leave his Jewish identity behind. One of his most poignant stories, “The Slovo Stove,” from 1985, is also one of his most Jewish works, though not explicitly so. The stove is a relic from the old country that heats food without ever getting warm. No one knows how it works, but instead of marveling at its fantastical properties, the younger generation is ashamed by it:

“We’re Americans, ain’t we?” [Nick] yelled. “So let’s live like Americans; . . . I’m tired of all them Old Country ways, what next, what else? Fur hats? Boots? A goat in the yard?” He addressed his wife. “A hundred times I told your old lady, ‘Throw it away, throw the damned thing away, I-am-tired they making fun of us, Mamma, you hear?’ But she didn’t. She didn’t. So I, did.” . . .

Nick threw his cigarette with force onto the linoleum and, heedless of shrieks, stamped on it heavily. Then he was suddenly calm. “All right. Listen. Tomorrow I’ll buy you a little electric stove, a, a whadda they call it? A hot plate! Tomorrow for your own room I’ll buy y’a hot plate. Okay?”

The story, Michael Dirda wrote, is a celebration of the “vanishing cultures and foods and customs and places, most of them now absorbed in the homogenized tele-glitz of modern American mall-life.” This is well put, but biographically, “The Slovo Stove” also calls back to Davidson’s youthful religious writings. It is a critique not only of postmodern American culture but specifically of those who are too quick to dismiss tradition and deprecate its rituals.

When the stove is destroyed, the story’s protagonist, Fred Silberman, searches for its remains. If only they could be scientifically tested, he thinks, the stove’s secret might be revealed. But even the shards have vanished, fastidiously swept away: “That incredible discovery, mysteriously having come to earth who knew how and who knew how many thousands of years ago or how many thousands of miles away. It was gone.” The story is Davidson at his best: immersive, weird, with a touch of transcendence.

Davidson’s writing never brought him much in the way of income. In 1980, health declining, he moved to Washington State. In 1985, he lived for a time in the veterans home in Bremerton, cantankerous, partially blind, and using a wheelchair. When he was hospitalized a few years later, he refused to eat pork. “I am a Jew,” he told the staff.

Davidson’s life ended in 1993 as it had been lived, between worlds. Ethan found a note with last instructions pinned to the apartment wall:

In the event of my death: What a foolish phrase. Of course I am going to die. When I die, I want to be cremated, and I want the ashes to be buried at sea by the United States Navy, with whom I had the honor to serve. And I want a marker to be placed in a military cemetery with my name on it and a Star of David.

Avram Davidson searched for God his whole life, but God can be elusive. His wanderings ended with his ashes scattered upon the Pacific, but a grave marker in the San Francisco National Cemetery bears his name and a Jewish star.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

From King James to Koren

The new Koren Tanakh smoothly addresses some thorny questions of biblical translation, including this one: Are there dolphins in the Torah?

The Best Unicorn

Peter S. Beagle's classic fantasy novel The Last Unicorn perhaps betrays its Jewish bent with "idiosyncratic yet archetypal characters such as the hapless magician Schmendrick."

Out-of-Body Experiences: Recent Israeli Science Fiction and Fantasy

The Yarkon is as good a site as any for pondering the relationship between Israel and the imagination.

Exit, Loyalty … Crowdsource?

It is a bit of a surprise to open a big-think policy book on the fate of the Jewish people and read a Jason Bourne scene with a prep-school payoff, but Tal Keinan is entitled to it.

gershon hepner

Unprofitable Belief in God and Politicians

A cantor on the day that’s designated for atonement, Yom Kippur

praying in a synagogue whose congregation all were disbelievers

wondered whether God preferred the prayers of all he people who were sure

that He existed. Although many rabbis do, cantorial prima divas

more often don’t, their income corelating with the beauty of their voices which

elicit only rarely a response from God who, like politicians,

relies on the performance of voices of supporters whose melodious pitch

programs their pitches for what often are unprofitable petitions,

Though in the olden days according to the Bible they were profitable,

in our times in our disbelieving world no citizens are prophetable.