Washington’s Saving Shield

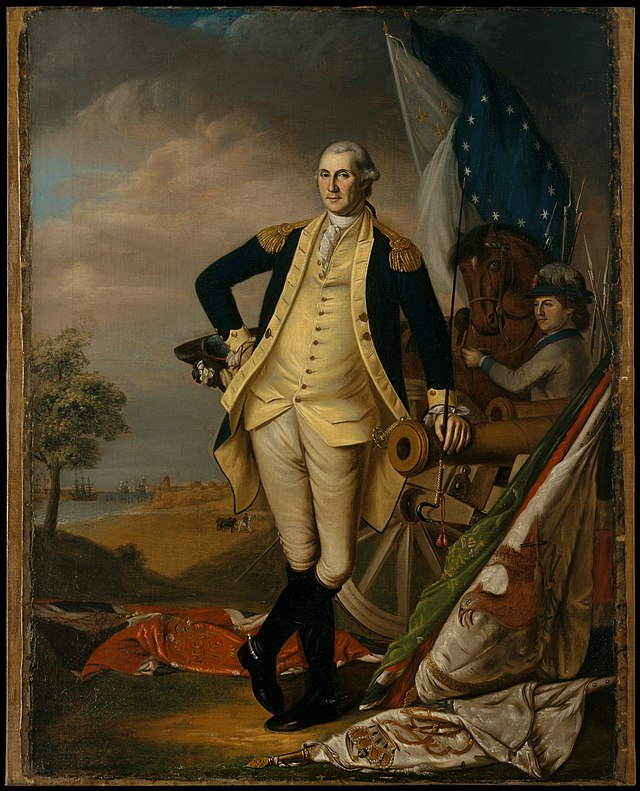

Shortly after the end of the Revolutionary War, Hendla Jochanan van Oettingen of New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel prayed for George Washington, the future president. As Americans mark Washington’s birthday this Monday, February 19th, it is worth examining the brief prayer, composed 240 years ago in Hebrew.

Van Oettingen led the community in the prayer himself that day. After praising God, he pivoted to the war, just recently ended, in a style resembling the Psalms:

We cried unto God from our straits and from our troubles He brought us forth. And for us, a weak people, inhabiting the land, He in His goodness prospered our warfare. You have restored us our inheritance from the hands of aliens and strangers and given us back the joy of our heart.

The “we” here includes not only the Jewish community but all Americans; the “aliens and strangers” are clearly King George III and the redcoats.

It is in the next section that the connection between the Jewish community and the character of the newly founded country is made:

Hear the prayer of your first-born son, your chosen people, who trust in your thirteen attributes of mercy, that they return not empty from before you, faithful sons of faithful believers in the thirteen principles of your Law. As you gave of your honor to David son of Jesse and to Solomon his son [whom] you gave wisdom greater than that of all men, so may you grant intelligence, wisdom, and knowledge to our lords, the rulers of these thirteen states.

It is a remarkable collection of allusions. Eight decades before President Abraham Lincoln would refer to Americans as God’s “almost-chosen people,” Van Oettingen tied ancient Israel to the future of the United States, and invoked its two greatest kings, David and Solomon, as models of leadership for “our lords, the rulers of these thirteen states,” whom, the community prays, God will similarly support.

The deep connection between the Jewish people and their newly independent country is underlined by the prayer’s focus on the number thirteen. It seems almost providential that the thirteen states correspond to God’s thirteen attributes of mercy, which Moses learned from God at Sinai (Exodus 34), and Maimonides’s thirteen principles of faith.

Earlier, in 1766, the American Jewish community had prayed that God “preserve, guard, and assist, our most gracious Sovereign Lord, King George [III], our gracious Queen Charlotte, their Royal Highnesses George Prince of Wales, the Princess Dowager of Wales, and all the Royal Family.” A decade later, at the Revolution’s fraught start, they had called for “everlasting peace between Great Britain and her Colonies, as in former times.” Now, as historian Jonathan Sarna has noted, the freshly American congregation marked the “abolition of subservience” to the Crown by sitting, rather than standing, as van Oettingen led the prayer celebrating freedom and its fighters. First among those fighters, of course, was Washington himself. Just as God had enabled Samson to “rent a young lion in his might, so may you strengthen and support the saving shield of our lord and commanding general George Washington, the appointed chief of the war on sea and on land.”

Amid the ashes of a war recently ended, Van Oettingen also invoked Isaiah’s famous vision. “How beautiful might it be,” he continued, “would you confirm the peace that you have planted on the hearts of kings and rulers that they should beat their swords into plowshares, their spears into pruning forks, that nation should not lift up sword against nation nor should they any more learn war.”

While the prayer celebrated newfound liberty in exile, it also wished for the restoration of the people of Israel to their homeland. “As you have granted to these thirteen states of America everlasting freedom, so may you bring us forth once again from bondage into freedom . . . and the dispersed . . . shall come and bow down to the Lord on the holy mount in Jerusalem.” It was, perhaps, a testament to the already manifest values of religious freedom that such a hope could be expressed so publicly.

As President George Washington himself would famously phrase it later in a letter to the Hebrew Congregation at Newport, the United States was to be a place in which toleration was no longer “spoken of as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights.” Washington concluded “May the father of all mercies . . . make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in his own due time and way everlastingly happy.” Amen.

Suggested Reading

Law, Justice, and Memory in Poland

Under the Law and Justice Party, Poland has just criminalized the life stories of its Jewish survivors. Here’s why.

Diminished Light?

Can a new book on tzimtzum expand our knowledge of that esoteric concept?

Comes the Comer

The New American Haggadah boasts a high-profile cast of contributors—Jonathan Safran Foer, Nathan Englander, Nathaniel Deutsch, Jeffrey Goldberg, Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, and Lemony Snicket. But it also features a series of unfortunate translations and commentaries.

Succession, Secession!

The notion of zera kodesh, “holy seed,” appears only twice in the Bible, both times in reference to the people of Israel as a whole. For Hasidim, however, it has a more restricted meaning.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In