Kaddish for the Maestro

Bradley Cooper didn’t win an Oscar for Maestro as star, director, or cowriter, but he deserves all the praise and gratitude that can be mustered for making a major film about a classical musician in America. As an actor, Cooper largely succeeds in conveying the dauntingly complex and contradictory dimensions of Leonard Bernstein’s personality, including his prodigious musical gifts, not only as a conductor, composer, and pianist but as a teacher and public intellectual.

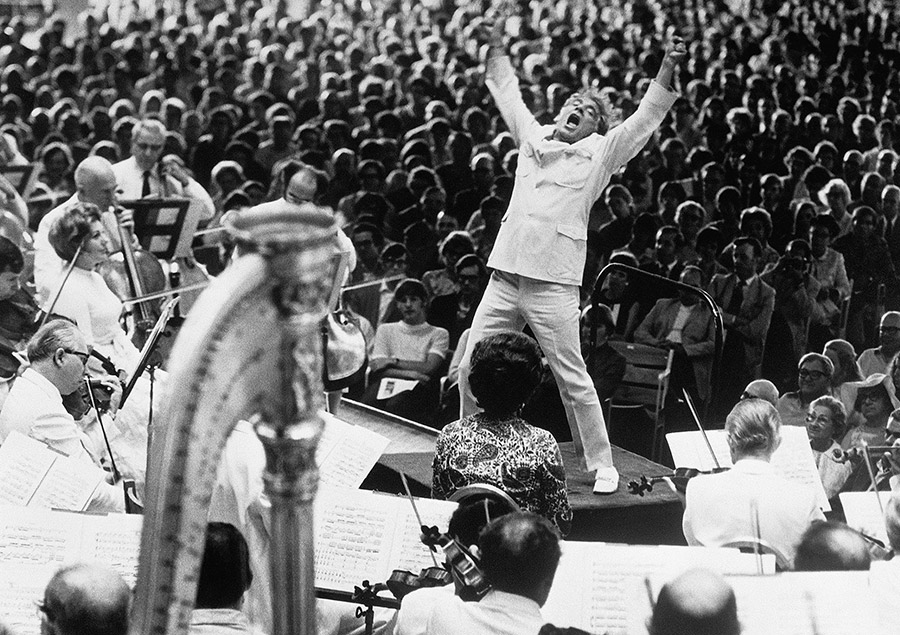

Bernstein was also an extraordinary physical presence—strikingly handsome and enormously expressive. His approach to conducting stood in stark contrast to previous generations of conductors. He transformed conducting into visual theater. Bernstein was visually mesmerizing in ways neither Arturo Toscanini, the previous great podium celebrity, nor his mentors and teachers, including Serge Koussevitzky, Fritz Reiner, and Dimitri Mitropoulos, ever aspired to. Bernstein offered the public something new: a pantomime of the music, a varied gestural narration of the music’s emotional meaning as understood by the conductor. To follow it required no prior knowledge. Bernstein used his entire body, occasionally even leaping from the podium. He made watching the conductor central to what it meant to attend a concert.

Richard Strauss is supposed to have said that a conductor should never sweat; only the audience should. But underlying Bernstein’s antics (which were widely derided by critics during his tenure at the New York Philharmonic from 1957 to 1969) was a near total command of the traditional techniques of conducting with hands, baton, and facial expressions. These Bernstein learned at the Curtis Institute of Music from Reiner, who was resolutely inert, using only his wrist and eyes to create technically brilliant and dramatic performances. But Bernstein went on to develop a broad and subtle arsenal of movements, both novel and time honored, that he mobilized to realize his irrepressible intuition and spontaneity as well as his empathetic and analytic drive as an interpreter of the music of others.

This is an enormous challenge for any actor to replicate, and Cooper has said that he worked on it, on and off, for the six years that the film was in development. He gives a creditable imitation of how Bernstein stood and sat in rehearsals, handled the baton, and executed subdivisions of beats. Toward the end of the film, in a scene depicting an older Bernstein teaching at Tanglewood, Cooper demonstrates to a novice how to guide an orchestra out of a fermata, or hold, that stops the flow of musical time. In this case the fermata is quite straightforward—it appears toward the end of the first movement of Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony. The technical problem, like its solution, is rudimentary, but Cooper has figured out how to demonstrate the resumption of the music by reestablishing the pulse of the movement.

Things do go off the rails every once in a while (and understandably so), as in one of Maestro’s longer musical episodes, a re-creation of Bernstein’s legendary 1973 filmed live performance at the Ely Cathedral in England of Mahler’s Second Symphony, a favorite of Bernstein’s. Cooper’s account of the closing five minutes of this grandiose work emulates the actual video of Bernstein’s performance (you can see it on YouTube), but it veers toward a parody of Bernstein’s already extravagant gestures and facial expressions.

Then again, no musician, not even Herbert von Karajan, Bernstein’s far less admirable main mid-century rival, has left behind such an extensive visual legacy. Playing Bernstein is a little like having to play JFK or a Beatle. The original videos are still familiar to many and only a click away for the rest of us.

Cooper’s struggle to portray a quite literally inimitable conductor is partially compensated for by his persuasive portrayal of Bernstein as a fabulous pianist, including a wonderful early scene at the party at which he first meets his future wife, Felicia Montealegre. He is also convincing in the few scenes that show Bernstein composing. Unfortunately, less of Bernstein’s music comes through in Maestro’s soundtrack than one might have hoped. There are wonderful snippets of his early work, from On the Town, Fancy Free, and Four Anniversaries. And there is just under a minute from Bernstein’s Second Symphony, the spectacular Age of Anxiety, which was inspired by Auden’s long poem and features a brilliant jazzy solo piano part that Bernstein both played and conducted, notably with his equally versatile friend Lukas Foss at the keyboard. West Side Story, Candide, Chichester Psalms, and Mass all make cameo appearances too. Although some of these musical bits and pieces work within the dramatic structure of the film, they are too short to give a persuasive sense of them as music. The same is true for the excerpt from Bernstein’s Third Symphony, Kaddish, which appears at the end of the film.

(Photo by Lee/Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.)

During his lifetime, Bernstein was routinely dismissed and derided as a lightweight and conservative composer. Calling him Lenny was an endearment from a public who loved, and felt they knew, Bernstein, but it could also be a putdown. Posthumously, however, Lenny has had the last laugh. It is not as a conductor but as a composer of Broadway shows, songs, music for dance, and concert music, including the Serenade for violin and orchestra based on Plato’s Symposium (one of his best works strangely absent from Maestro), that Bernstein will be remembered by future generations.

One skill that made Bernstein a star, recognizable the world over, was his unique ability to speak with clarity and eloquence about music, its logic and structure, and its links to history and ideas. He never buried his love of music under an avalanche of ideas and facts when he was speaking to the public. He spoke magnificently before live concert audiences, over the airwaves, and on screen. Bernstein’s verbal virtuosity does not come across particularly well in Maestro. Even when he was not speaking extemporaneously, he wrote his own scripts. And yet the one scene in which Cooper imitates Bernstein speaking directly to an audience (about Shostakovich) is oddly lame, self-centered, and sententious:

What I love about these Thursday rehearsals is that we get a chance to talk to you about what we think of the music. . . . Today we’re studying Shostakovich’s 14th, opus 135. What I realize, about this piece, and it could be morbid but I tend to think that it’s not, is that as death approaches, I believe that an artist must cast off anything that’s restraining him. And an artist must be resolute in creating, with whatever time he has left, in absolute freedom. . . . And that’s why I have to do this for myself. I have to live the rest of my life, however long or short that may be, exactly the way that I want, as more and more of us are in this day and age.

What was great about Bernstein’s talks about music, whether at his Young People’s Concerts or on occasions like this, was that although he always spoke in a personal voice, he was not really speaking about himself—it was always about the music and in service of the audience. (It was only when he felt called upon to theorize, as in his inchoate Norton Lectures at Harvard, published as The Unanswered Question, that Bernstein tended to tie himself up in knots.)

If Maestro does not quite succeed as a portrait of the maestro, it is because it is not quite about him, in the end. Rather, it is a finely delineated psychological portrait of his wife, the mother of their three children. Felicia Montealegre was just as beautiful, gracious, and charming as Carey Mulligan plays her. She was also herself exceptionally gifted as an actress on stage and the small screen during the first golden age of television.

Mulligan captures Felicia’s legendary kindness, her talent and wit, and her extraordinary friendship with and love for Bernstein. Their relationship was unusually complex, since Bernstein was—as Felicia understood from the start—fundamentally homosexual. Bernstein’s attraction to men tormented him in his early years and even led him to seek a therapeutic cure. As time passed and attitudes changed, he came to embrace who he was. His life as a homosexual gradually dominated his strong sexual appetite, particularly in his last years after Felicia died. (This, in fact, is the not very subtle subtext of the Shostakovich talk in the movie.)

For decades, Felicia did most of the work in sustaining their marital relationship. She nurtured her loving devotion to Bernstein while maintaining the public facade his fame and career demanded. There is little doubt that they truly loved one another and succeeded in raising a happy family together. But all this required extraordinary self-sacrifice and empathy on Felicia’s part. That is the story that Maestro tells.

One of the stories that Maestro doesn’t tell is of Bernstein’s lifelong engagement with American politics. His senior thesis at Harvard dealt with the importance of Black music (“race elements,” in the language of the time) in making American music distinctive and not merely imitative of European models. Throughout his life, he opposed racial discrimination and was an avid proponent of civil rights. In this respect, Tom Wolfe was unfair in his famous account of the Bernsteins’ fundraiser for the Black Panthers in their Park Avenue apartment as mere “radical chic.” However misbegotten that particular event may have been, the Bernsteins were not hypocrites; their political commitments ran deep.

Bernstein was also an early advocate of nuclear disarmament. At the same time, he participated in official American diplomacy after the 1956 thaw. In 1959, he made a momentous visit with the New York Philharmonic to Russia, where they were greeted with great critical acclaim and cheering crowds. During the tour, Bernstein arranged a clandestine meeting with Boris Pasternak, the poet and author of Doctor Zhivago, who was out of favor with the regime and had been prevented from

accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Bernstein understood music as a means to articulate universal human values. He also thought that the causes of democracy, freedom, and justice demanded active civic engagement from artists in the public eye. Bernstein’s last and perhaps most famous use of music to make a political point was his performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall, on December 23, 1989. Lest his point not be grasped fully, he altered the text of the choral finale, an “Ode to Joy” (whose melody became the anthem of the EU) by replacing “Freude” (Joy) with “Freiheit” (Freedom).

Politics, however, is not the most egregious omission in Maestro. The film tiptoes around Bernstein’s Jewishness. His sense of himself as a deeply committed Jew and a fierce advocate of the State of Israel was central to both his self-conception and his art. There is only one episode in the film that highlights Bernstein’s Jewishness. At a lunch at Tanglewood, his mentors Aaron Copland and Koussevitzky worry that their young genius is frittering away his talents on Hollywood, Broadway, and perhaps other unmentioned temptations instead of becoming “the first great American conductor.” But they also have another perhaps more pressing worry. Koussevitzky says, “And the name . . . to a Bernstein they will never give an orchestra. But a Burns? Leonard S. Burns.” Bernstein replies only that he’d “have to sleep on that” but clearly dismisses the suggestion out of hand. This is characteristic of Bernstein. He was a proud American Jew in a way that his older Jewish mentors—Copland was the son of Eastern European Jewish immigrants and Koussevitzky was one himself—could not quite comprehend.

Bernstein’s pride in his Jewish identity reappears again in Maestro but only as a discreet visual detail. In a crucial scene late in the film, Felicia urges Lenny to speak with their teenage daughter Jamie to deny rumors she’s heard about his homosexual affairs at Tanglewood. He walks out onto the back porch of their Connecticut house to talk to Jamie in a crimson sweatshirt with “Harvard” emblazoned across the front in Hebrew. Maestro was released in November of last year. The cunning of history, in the form of October 7, 2023, and the explosive campus reaction at Harvard and elsewhere made this oblique nod to Bernstein’s intense Jewish pride and allegiance to Israel awkward, if not discordant.

Bernstein, like many others in his generation, had no difficulty reconciling his left-wing political beliefs with his ardent Zionism. In the fall of 1948, he traveled to perform for the troops and the civilian population of the newly created State of Israel. He returned frequently and played with the Israel Philharmonic throughout his career. He was there in 1967 to celebrate Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War; he prayed at the Western Wall and performed Mahler on Mount Scopus before an enormous crowd.

Bernstein’s unwavering Jewish loyalty started at home. His father, Samuel, who is given somewhat short shrift in Maestro, was a successful salesman of beauty products who wanted Lenny to join the family business and worried that he might end up some kind of itinerant klezmer musician instead. But Samuel was also something of a talmid hakham and a proud descendant of a long line of rabbis. It was the family membership in Brookline’s Mishkan Tefila, the Boston area’s first and foremost Conservative synagogue, that exerted the greatest influence on Bernstein. By the 1930s, the Conservative movement had managed to fashion a distinctively American Judaism that was neither high German Reform nor heimishe Eastern European Orthodoxy. It promoted what Bernstein later described as a theology of “liberalism, Zionism and social service” framed within a modernized but recognizable adherence to traditional Jewish practice.

The young Bernstein fell in love with the music of his shul and often acknowledged its cantor Solomon Gregory Braslavsky as having exerted a lasting influence on his ambitions as a musician. He became determined as a young man to be the first major Jewish American composer to foreground Hebrew religious texts in his music, and he succeeded spectacularly. His first symphony, Jeremiah, was written in 1942 during the war and included verses in Hebrew from Lamentations. Bernstein also composed a series of Jewish choral works in the late 1940s, all with the texts of Hebrew prayers. His Kaddish symphony from 1963, which was dedicated to the memory of President Kennedy (whom he of course knew), combined the Aramaic text of the Kaddish, quotes in Hebrew from the liturgy, and Bernstein’s own English language of a Job-like conversation between man and God. In one of his most performed works, the Chichester Psalms (1965), Psalms 23, 100, 131, and parts of others are sung in Hebrew. At the end of his career, in 1989, Bernstein made final revisions to Opening Prayer, a work originally written to celebrate the 1986 renovation of Carnegie Hall. It is a setting of the biblical blessing of the kohanim to the people of Israel (and of fathers to their children on Friday evening).

Such forthrightly Jewish music stands in stark contrast to the compositions of Bernstein’s most influential compositional mentor Aaron Copland. Copland invented a classical music that expressed the American spirit. He was confident that he could represent America to itself and to the world with works such as Billy the Kid, Rodeo, Appalachian Spring, Lincoln Portrait, and Fanfare for the Common Man. Copland’s masterpiece, the Third Symphony (a particular favorite of Bernstein’s), fully expressed the majesty of the American landscape and its democracy, but there was not a hint of anything recognizably Jewish in it, apart, perhaps, from its idealism.

Bernstein’s significant role in the early years of Brandeis, America’s first secular Jewish university, should also not be forgotten in this regard. He came as a visiting professor in 1952, founded the Festival of the Creative Arts, and was instrumental in building its great music program. The department included several of Bernstein’s Jewish musician friends from Harvard, particularly Irving Fine, whom Bernstein adored (and whose symphony from 1962 he championed), Arthur Berger, and Harold Shapero.

Bernstein’s career overlapped with a critical mass of Jewish émigré musicians who fled the Nazis, including great instrumentalists and conductors: Elman, Heifetz, Horowitz, Serkin, Koussevitzky, Rubinstein, Reiner, and Szell. There were also American-born Jewish stars like Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern. And then there were composers, including Blitzstein, Copland, William Schuman, Eisler, Gershwin, and Weill, not to mention Broadway figures such as Richard Rodgers and Bernstein’s own collaborators Alan Jay Lerner and Stephen Sondheim. Nonetheless, Bernstein turned out to be unique. He achieved an incomparable public profile and popular following without minimizing or camouflaging his status as a proud Jew in America.

Bernstein fulfilled, as perhaps no other contemporary American Jew had, the cultural aspirations of the Conservative Judaism in which he was raised. This is not to say that he was without Jewish peers in the firmament of postwar America, including, say, Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Ben Shahn, Louis Kahn, and Jonas Salk, not to mention Sandy Koufax (or Lenny Bruce). But Bernstein was not merely proud of his Jewish identity; he was positive about Judaism itself. His theology may have been a vaguely Spinozistic mystical naturalism, but Bernstein was comfortable davening in shul under a tallis in a way that few other midcentury Jewish American cultural heroes were.

Bernstein’s Spinozism was one of the things that led him to his advocacy for, and nearly obsessive identification with, Gustav Mahler. Like Bernstein, Mahler was an avid reader of philosophy and literature and conceived of writing and performing music as a spiritual, quasireligious quest for truth and personal transcendence. They were also both pianists, conductors, and composers, esteemed in the first two roles but condescended to in the third—a critical judgment that haunted them both. The key difference between Bernstein and Mahler was Mahler’s characteristically European ambivalence about being Jewish. He never lost a sense of his fundamental homelessness, of being irrevocably an outsider, even after he converted to Catholicism. Bernstein, needless to say, never felt a need to abandon Judaism, and he came to believe that he could somehow fulfill Mahler’s own dashed hopes for cultural and artistic acceptance as his natural successor.

Bernstein’s success in catapulting Mahler into the center of the symphonic repertory in the 1960s made his later conquest of Vienna as a conductor profoundly important to him. Starting in the 1970s, Bernstein conducted the Vienna Philharmonic regularly and became the darling of the Viennese audience. The city that was said to have rejected Mahler in 1907 (after which he left for New York) now embraced Mahler’s reincarnation in the form of Leonard Bernstein. Nothing so completely met Bernstein’s criteria of success as the adulation accorded him in the legendary “city of music.” So strong was Bernstein’s psychological need for public vindication in Vienna as the new Mahler that he enthusiastically befriended more than a few former Nazis, including the conductor Karl Böhm, who all continued to hide their pasts. In this naivete, too, he was perhaps distinctly American.

Leonard Bernstein’s American Jewish story remains invisible in Maestro. The most poignant dimension of his career—his realization of the unique promise that the American diaspora possessed for Jews—is lost, if not avoided. The Bernstein family life in Maestro shows no markers of a Jewish home. There are no Shabbat candlesticks or hannukiah, not even a plate of gefilte fish. The only holiday the viewer sees the Bernstein family celebrating is a tense Thanksgiving. In the end, little remains of the maestro’s Judaism beyond that Hebrew Harvard sweatshirt and Bradley Cooper’s much-discussed prosthetic nose.

From the vantage point of 2024 and the startling revival of antisemitism, including the demonization of Israel among progressives on the American political left, Bernstein’s career, like the bygone prestige and prominence of the Conservative Judaism in which he was raised, seems like a fantastic dream from which we have suddenly awoken.

Leonard Bernstein’s musical legacy will survive. But there will be no encore of his well-deserved but historically miraculous rise to fame and influence as a Jew in America, not even in music.

Suggested Reading

The Other Bernstein

Late August 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of Leonard Bernstein’s birth and the first Yahrzeit of his brother, Burton, who wrote an incredible family memoir.

Tradition! Tradition!

Wonder of wonders! One of the most beloved musicals ever created far outstripped its own creators' expectations for its success.

New Beats for Old Brooklyn

Andy Statman started out as an unlikely prodigy: a New York Jewish kid playing bluegrass on the mandolin.

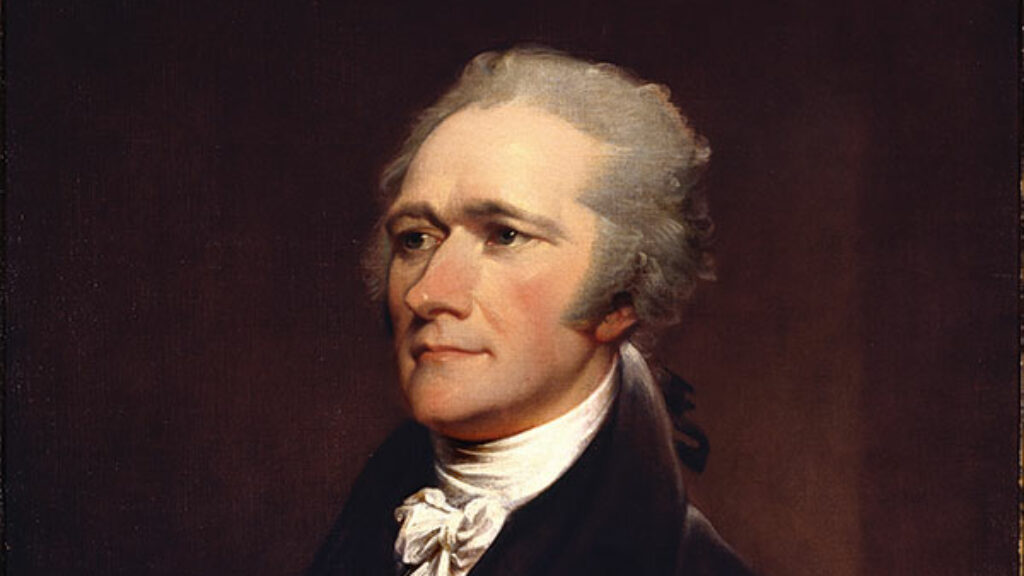

Ten Duel Commandments

Alexander Hamilton was, as the song goes, a “bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman.” Was he also a Jew? Well, he did go to Hebrew School in the West Indies, but ...

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In