A Good Golus

One day when I was young and easy under the red-roof tiles and as happy with my growing family as the Hollywood Hills were green (when you could see them through the smog), I walked up to the corner of Sherbourne and Pico on some small errand and ran into a guy I’ll call Charles. We weren’t exactly friends, but we’d met the previous year in Jerusalem. He was a grad student in a prestigious humanities program (a status to which I aspired) and the first person I’d ever heard use the word “problematize” in more or less casual conversation. I tried to avoid him, but he walked straight up to me. “Well,” he said, “this is a good little golus you’ve got here.”

He said it in a condescending tone (he said almost everything in a condescending tone), but he wasn’t wrong. That little square mile of Pico-Robertson had maybe a dozen shuls and two dozen kosher stores and restaurants (or vice versa). You ran into all kinds of Jews on the street: Modern Orthodox young professionals, expat Israelis, egalitarian traditionalists, Hasidim, aspiring screenwriters, and various kinds of Jewish refugees: religious Iranians, secular Russians, and European survivors who had moved into the neighborhood a generation ago. Not to speak of the occasional grad student or the Kabbalah Centre missionaries (who weren’t always Jewish). If we were in exile, Charles was right that it was a pretty good one.

Once, Shoshana and I invited our friend Avi Davis, of blessed memory, over for Shabbos dinner, but he’d forgotten exactly where we lived. He wandered up and down the street of almost indistinguishable postwar apartment buildings knocking on doors and eventually ended up eating with a nice older couple who invited him in.

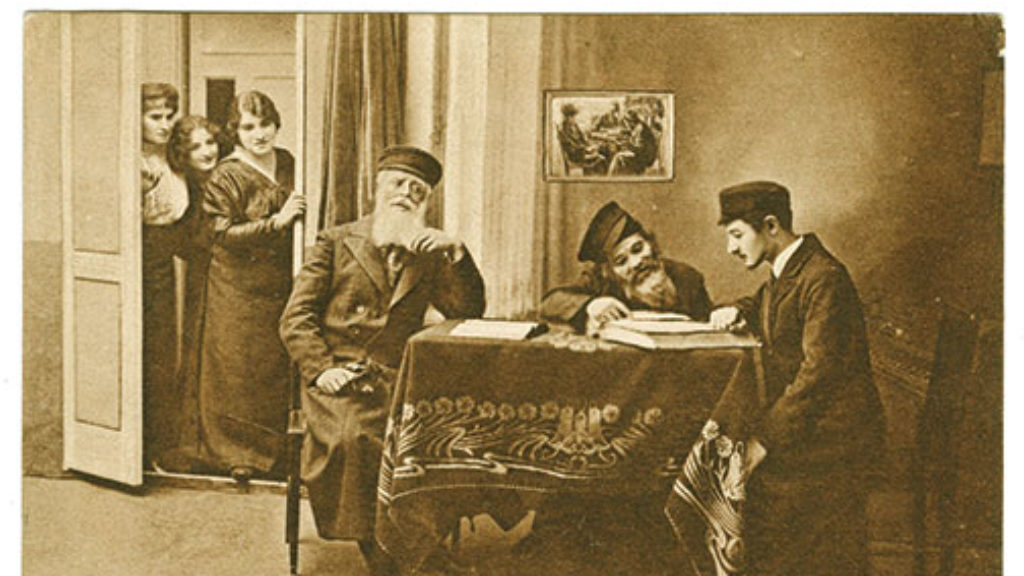

On another Friday evening, I was walking to shul with my daughter Anna, who must have been three-and-a-half at the time, when we passed an old Hasid with a white beard, who might have been a rabbi or a donkey driver in the old country. “I saw God,” she said matter-of-factly as he hurried down the street. The remark shocked and moved me so much that I didn’t even give her my Maimonides-for-children speech. They tell a similar story about the kids who saw Martin Buber walking on the streets of Jerusalem. The synchronicity, if that is the right word, of my daughter’s remark and the Buber anecdote is the only thing that has ever made me wonder if Jung was right about the collective unconscious and archetypes (or anything at all).

This summer, walking down Jaffa Road in Jerusalem, I passed a cafe with a crowded bookshelf of used paperbacks for sale out front. I didn’t turn up anything I needed (it was my fourth bookstore of the day), but I did see a paperback copy of Saul Bellow’s stories in Hebrew. The cover of Hasippurim Hanivcharim features a black-and-white photo of the author in his dapper man-about-Chicago middle age, wearing a snappy, short-brimmed fedora and a skinny tie. A blurb from Philip Roth floating beneath him reads: ee efshar lehavin et ha-sifrut ha-amerikanit bli likro et sol belo (“It is impossible to understand American literature without reading Saul Bellow”). As always, Roth chose his words carefully (albeit in English): American literature, not American Jewish literature.

Midcentury America was a good golus, to say the least, but Roth was claiming much more for Bellow (and himself). In The Green Hills of Africa, Hemingway famously said that modern American literature began with The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Roth was saying that if Huck was at the headwaters of American literature, you couldn’t float down that muddy river without passing through The Adventures of Augie March. Or, as Augie introduced himself, “I am an American, Chicago born—Chicago, that somber city—and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way: first to knock, first admitted . . .”

I live in a good golus now too, a leafy little suburb in Greater Cleveland called Beachwood. At one time, the town was 90 percent Jewish, second only to the Satmar city of Kiryas Joel in upstate New York. Most of Beachwood’s residents, however, were affluent, liberal and largely assimilated Jews. The city has changed over the last twenty-five years or so, becoming somewhat less Jewish (65–70 percent, if I had to guess), but far, far more Orthodox.

The frumming of Beachwood did not go easily. In the late 1990s, the Jewish mayor and city council members of Beachwood, many of whom belonged to Reform congregations, tried to keep two Orthodox synagogues from being built on the basis of zoning laws. Curiously, in the 1950s, the non-Jewish mayor and city council of Beachwood had tried the same legal strategy (accompanied by some of the same noxious rhetoric) to keep Anshe Chesed, Cleveland’s oldest Reform congregation, from moving into Beachwood. Beachwood lost in the Supreme Court of Ohio both times.

This spring, Anshe Chesed Fairmount Temple, which is around the corner from me (and from a dozen thriving Orthodox shuls, including mine), and The Temple-Tifereth Israel, which is not much further, voted to merge their two diminished congregations and sell off the Fairmount property. Anshe Chesed was founded in 1842 and The Temple, as Tifereth Israel is often simply and unironically called by locals, started just eight years later when some members broke away, as Jews will, to found the new congregation.

In August, I belatedly heard that Fairmount Temple was liquidating its library, and arrived just before the librarian and volunteers had to exit the building. Surprisingly, there were still a couple of thousand books on the shelves, from late twentieth-century beach reads to almost the complete works of Bellow, Roth, Ozick and others to classic works of Jewish scholarship; all of them hardbacks, with their original jackets meticulously preserved under plastic Brodart covers, and all of them unredeemed. Some mordant browser (or dybbuk) had propped up a copy of Someday the Rabbi Will Leave, the last of Harry Kemelman’s bestselling series about a mystery-solving Reform rabbi. There was also a framed news photo of Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld, who presided over the congregation from 1958 until 1986, battered and bleeding after being attacked with a tire iron by Mississippi segregationists during the Freedom Summer of 1964.

I headed for the periodicals room. A run of the first sixty years of Commentary had already been taken, but there was still a century’s worth of great magazines. With the clock ticking and only two boxes, I grabbed the first decade of the Menorah Journal. Its 1916 inaugural issue features Louis Brandeis a few months before he joined the Supreme Court and Harry Wolfson a few years before he became a Harvard professor. Back among the books, I found Messianic Speculation in Israel, by Abba Hillel Silver, the American Zionist leader who led The Temple-Tifereth Israel from 1917 until his death in 1963.

I also ran into the little Dell paperback of Saul Bellow’s anthology, Great Jewish Stories. In his introduction, Bellow tells a story about visiting S.Y. Agnon in Jerusalem:

While we were drinking tea, he asked me if any of my books had been translated into Hebrew. If they had not been, I had better see to it immediately, because, he said, they would survive only in the Holy Tongue.

Bellow had little Hebrew and Agnon had less English, so they must have been speaking in Yiddish, which means that Bellow wasn’t being arch or ironic when he wrote “the Holy Tongue,” he was just translating Agnon’s “Loshn-Koydesh.” But they both probably appreciated the irony in his making the case for literary Zionism in the language of golus. In any event, Bellow was charmed, but not entirely. Elsewhere, he wrote that “the only life I can love, or hate, is the life that I—that we—have found here . . . the life of Americans who are also Jews.” I identify with that “we” of Bellow’s, and I would no more try to read his great-books-and-gangsters prose in Hebrew than I would try to light out for the territories with Huck in the Holy Tongue.

And yet, when I looked at Bellow’s unclaimed shelf of novels in this decommissioned temple of twentieth-century American Judaism and remembered the Hebrew translation of his stories lying in a Jerusalem bargain bin, I could not help thinking that Agnon had overestimated the power of Hebrew, and I worried about the American life we have found here, this good golus.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Books vs. Children

"Apparently it is very troubling for children to see their parents working, at least doing the kind of work that does not make itself visibly obvious."

Middlebrow’s Moment

In the 1950s, Americans were introduced to Judaism. But what kind of Judaism, exactly?

People of the Book World

"The Jewish market has become quite a good one,” a Knopf editor observed; even the “goy polloi” were buying, wrote another staffer.

What’s Yichus Got to Do with It?

For the whole history of Jewish society, until less than two hundred years ago, love and attraction played little or no role in the making of marriages, which were arranged and contracted according to the interests—commercial, religious, and social—of the families involved.

Allan Appel

Mr.Socher

I'm a lapsed subscriber but your piece about the golus in the City of Angels!, with its reference to the corner of Sherbourne and Pico inspired me to re-up. Not only because I enjoyed the literary journey you took your readers on, but also as that was my childhood neighborhood in the early to mid 1950s. And my first encounter with ancient bearded, God-like Jews occurred on that very corner where one of the shuls you referred to operated out of a grocery store (candy still in the display cases was one of the big draws and not infrequently used by the challenged melameds to bribe us to pay attention).....and of the eight or so novels I've written more than half emerged out of that world...ah well. thanks again for the warm surge of memory.

Allan Appel

https://www.allanappel.com/

JJ Gross

It seems Mr. Socher is using the term "golus" as a synonym for "ghetto'. But they are hardly the same, and certainly not interchangeable. Pico Robertson is definitely a ghetto, one in which one can pretend the entire world is Jewish, or that one is even living in Israel. A resident can get the illusion, if not delusion, that they are in a safe space impervious to any dangers lurking without. And there is nothing more dangerous than that. As for the fortunes of Beachwood, Ohio, it would seem the disappearance of liberal Jews and the shuttering of their temples is less an indication of relocation and more one of evaporation. Tragically, much of the American Jewish community - through a combination of reproductive indifference and self-abnegation - is melting aways rapidly. Exacerbating the situation in the reality that en route to ethnic oblivion, too many are moving from indifference to hostility -- especially among the young.

Patrick Henry Reardon

This was a marvelous account. It made me want to live in the neighborhood.

Deborah Marks

I am a brand-new and happy subscriber to JRB. Mr. Socher, I appreciated this bit of your vivid personal, community, and literary history; seeing the name of Harry Wolfson in relation to the 1916 inaugural issue of the Menorah Journal was an additional happy surprise.

I grew up in the 1950's on the Upper West Side (the Jewish side) of Manhattan. I attended an orthodox yeshiva through the 6th grade, and spent summers near Boston with my maternal grandfather, who was a close friend of Harry Austryn Wolfson's from their days as two of the few Jews at Harvard at that time. My toddler mother learned to pronounce Wolfson's tongue-twister title, Crescas' Critique of Aristotle, and to perform it proudly to amused guests, I'm sure including Wolfson himself.

I'm looking forward to your writing and future issues of JRB.