Like an Elevator

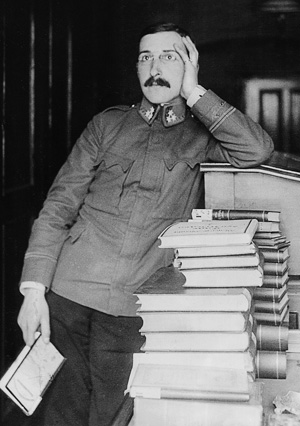

In the 1930s, when his fame reached its peak, Stefan Zweig had the distinction of being the most translated author in the world. He may also have been, as one critic put it, the world’s “most hated” author. For many of Zweig’s colleagues, his success was an object of envy, a sign of the times, and a badge of mediocrity, all at once. Zweig’s prominence was a “symbol,” according to Robert Musil, of the depths to which culture had sunk. Hermann Hesse complained that Zweig was “an intellectual rather than a poet.” The satirist Kurt Tucholsky treated the devotion to Zweig as a kind of unflattering shorthand:

Frau Steiner isn’t as young as she once was. . . . Every night she sits at her table, completely alone, wearing a different dress and reading from a finely made book. To bring this to a point, she adores the works of Stefan Zweig. Enough said? Enough said.

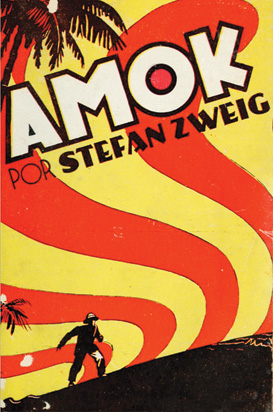

Another contemporary remarked that “Zweig created literature” out of “the feuilleton style—Viennese like Sachertorte with whipped cream, just as delicious and artful (and, unfortunately, just as sloppy).” Serious, but always accessible, close enough to the modernists to be measured against their standards, but far enough not to measure up, prolific on an industrial scale, Zweig found a sweet spot and became a lightning rod.

He wasn’t the only one, of course. Hesse himself had popularizing tendencies, and he, too, both profited from and paid for them. But Zweig elicited, and continues to elicit, an entirely different order of contempt. He remains a favorite on the “most embarrassing” and “most overrated” lists in German literary publications, and one recent critic went so far as to ridicule the style of his suicide note.

It wasn’t just the tricky combination of seriousness and mass consumption that put Zweig in the running for the title of most hated author in the world. Some have depicted Zweig as a nonpartisan cosmopolitan incapable of political courage. But the classic account of Zweig’s politics, Hannah Arendt’s 1948 essay “Stefan Zweig: Jews in the World of Yesterday,” developed a more sociological critique. In Arendt’s reading, Zweig possessed a “vanity that could hardly have originated in his own character.” Here, too, Zweig is a symbol, a symbol of a generation of assimilated Jews who eschewed “political values” for “cultural and personal” strivings, like the “idolatry of genius” and the pursuit of “fame.” This was caused, in Arendt’s view, by the conditions of the age, its combination of enfranchisement and exclusion. She writes, “For a Jew to be fully accepted into [Austrian] society, there was one and only one thing to do: become famous.”

The result, according to Arendt, was a blindness that fostered disaster: “Concerned only with his personal dignity, he [Zweig] had kept himself so completely aloof from politics that . . . the catastrophe of the last ten years seemed to him like a lightning bolt from the sky.” In despair over the loss of his celebrity, which was all he had, Zweig inevitably lost his will to live. Hence, Arendt reasons, his suicide in 1942 (in which he was famously joined by his young second wife). Like so many reckonings with Zweig, Arendt’s post-mortem didn’t have understanding as its main aim. Of his famous elegiac autobiography, The World of Yesterday, completed in Brazil just before his suicide, Arendt wrote:

It is astounding, even spooky, that there were still people living among us whose ignorance was so great and whose conscience was so pure that they could continue to look on the prewar period with the eyes of the nineteenth century, and could regard the impotent pacifism of Geneva and the treacherous lull before the storm, between 1924 and 1933, as a return to normalcy. But it is gratifying and admirable that at least one of these men had the courage to record it all in detail, without hiding or prettifying anything.

Anyone looking to gain a deeper sense of how Zweig in fact saw the world, and of what fame really meant to him, would do well to consult two recent books that complement each other nicely. Oliver Matuschek’s Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig is a cradle-to-grave, comprehensively researched affair and the most thorough Zweig biography to date. It’s smoothly written but a bit straight-laced. George Prochnik’s The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World focuses on Zweig’s final decade and the questions about exile it raises, branching out, often lyrically, into a winning mix of travelogue and family memoir.

Both works manage to display an attitude of impartial sympathy. Matuschek doesn’t shy away from relating many episodes in which Zweig’s behavior is off-putting to say the least. We learn, for example, that when Zweig found out he and the dying Gustav Mahler were on the same Atlantic crossing, he pretended that he wanted to be of assistance to Mahler and his wife, just so he could get close enough to gawk at them. For his part, Prochnik tells us at the outset that he regards Zweig not as a writer of genius, but rather as a person whose life refracts his times in a particularly vivid way. Both authors shine in bringing to light the complexity of Zweig’s life and art, blowing up, by implication, the array of clichés that Zweig’s memoir and his self-slaughter have done much to encourage. Thus, Matuschek quotes a 1918 letter to the French writer Romain Rolland, in which Zweig talks about how the “double pressure” of hatred toward Germany and hatred toward Jews will affect the collective psyche in Germany and, in turn, Zweig’s social world: “People of my ilk will be destroyed. They won’t even be allowed the little air they need to live.” “Spooky,” yes, just not in the way Arendt suggested.

Ultimately, however, Zweig’s infamously weak response to Hitler only goes so far in explaining the intensity of the scorn that was heaped on him, because the intensity peaked at least a decade before the Nazis came to power. How, then, to make sense of the cultural phenomenon of Zweig hatred? Zweig’s defenders tend to brush off the criticisms of his peers as nastiness from nasty people (Karl Kraus, Bertolt Brecht, Musil, etc.) If Zweig were really such a hack, his defenders ask, why do so many intelligent people like his works? Why the handsome new editions from Pushkin Press and The New York Review of Books Classics series? Those who find the resurgence of enthusiasm for Zweig distressing, on the other hand, cite early judgments of him as though their extraordinary biliousness were solely a function of Zweig’s extraordinary artistic failure. A better historical diagnosis might be that Zweig advanced, with an energy few could match, precisely the values, norms, and beliefs that his modernist critics wanted to oppose, while stubbornly operating in their orbit.

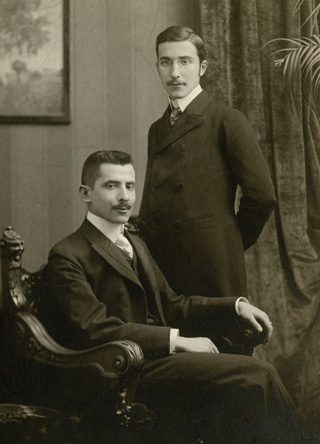

Stefan Zweig was born in 1881, into a bubble of bourgeois security—about as much of it as assimilated Viennese Jews could hope to have. His father was a staid, prosperous manufacturer of textiles, whose ascent was a function of prudence and thrift, rather than innovation or daring. Above all, Moritz Zweig prided himself on keeping the family business out of debt. “Stefferl,” as he was known within the family, led a very different life, which had its periods of sexual adventure and bohemianism. But he also seems to have inherited something of his father’s aversion to risk. Early on, Zweig wrote poetry, but he soon shelved that, and for the bulk of his career, he held closely to tried-and-true formulas for commercial success: novellas, biographies, and biographical essays, all of which seemed to pour out of him. Hence the fun that Karl Kraus, Zweig’s most relentless critic, had with his name: Zweig means “branch,” in German, and Kraus liked to refer to Zweig as “Erwerbszweig,” or “branch of industry.”

Zweig also shunned the avant-garde and wrote that one of the reasons why he decided not to relocate to Vienna after World War I, the better part of which he had spent in Switzerland, was that expressionism—or as he called it, “excessionism”—had taken hold in his home town. Instead, the newly married Zweig opted to restore and reside in a castle-like house in the hills above Salzburg, which he made into a reliquary of sorts, filling it with Beethoven’s desk, drawings by Goethe, signed editions, thousands of manuscripts, and so on. Zweig saw his collecting as a service, one whose impact would eventually be greater than that of his writing. Upon meeting Arthur Schnitzler, Zweig informed him that he had been buying up his correspondence—Schnitzler hadn’t even known his letters were for sale and responded by telling him that he had just burned several of his manuscripts.

But the deeper issue is that Zweig seemed to be promoting the calcification of the German cultural ideal of Bildung. For late-18th-century thinkers like Wilhelm von Humboldt and Johann Herder, the term “Bildung” had signified a dynamic process of self-development. Herder defined it as “being your own creator.” But what counted as Bildung had changed by Zweig’s day, devolving, in the eyes of critics like Nietzsche, into a fetishized source of prestige, something that could be acquired, consumed, and displayed, like Goethe’s drawings or Beethoven’s desk. For a critic like Kraus, Zweig’s “scribblings” about “the giants of world literature” (Montaigne, Hölderlin, Kleist, Dickens, Stendhal, Balzac, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Nietzsche, etc.) were of a piece with his collecting. They were presumptuous, implying, with their turgid flourishes, that their author was “on the same level as his subjects.” As Kraus saw it, Zweig was in the business of providing fake Bildung for “bourgeois readers.” Zweig, he wrote, “decorates the gap out of which their Bildung consists, making it warm and cozy.” He gives “an introduction to world literature with the maximal time savings.” All you have to do is step in, Kraus complained, and, “like an elevator,” Zweig’s biographies will “lift you up to the loftiest heights.”

When Freud read Zweig’s biographical essay on him, he was taken aback, because, as he put it, the essay overemphasized “all my bourgeois features.” Moreover, Zweig liked to smooth out the disparities between artists as people and the art they created. Great accomplishments reflected internal merit, hence the idea that Zweig advanced a “stock market humanism.” When a friend of Zweig’s brought up Wagner’s anti-Semitism, Zweig, who admired Wagner’s music, blanched. He “hated dissonance,” the friend recalled.

Karl Kraus begins an essay on Zweig by calling him “one of the representative schmoozers in European culture.” He contrasts his own preoccupation with linguistic “details,” or the aspect of his “method” that many saw as his own Jewish inheritance, with Zweig’s attempt to vault himself into the ranks of “world literature” by manufacturing Bildung. In doing so Kraus groups Zweig together with Emil Ludwig, another best-selling German-Jewish serial biographer; later he likens a grammatical misstep of Zweig’s to one committed by Felix Salten, another Jewish writer who aimed to insinuate himself into the center of Austrian culture.

This, I think, is the context against which Arendt’s critique of Zweig should be read. Her portrayal of Zweig as the shining example of failed assimilation, the parvenu par excellence, is illuminating less as a piece of socio-cultural analysis than as an example of that widespread sensitivity to the nexus of Bildung and Jewish integration, which Zweig, to the detriment of his reputation, exemplified as few others did. Here, again, is Arendt:

There is no better document of the Jewish situation in this period than the opening chapters of Zweig’s book. They provide the most impressive evidence of how fame and the will to fame motivated the youth of his generation. Their ideal was the genius that seemed incarnate in Goethe. Every Jewish youth able to rhyme passably played the young Goethe, as everyone able to draw a line was a future Rembrandt, and every musical child a demonic Beethoven.

No better document? Every Jewish youth? What would be the point of debunking Arendt’s prickly overreach when, to understand the virulence with which she and others reacted to Zweig, the point is the overreach itself?

For those interested in understanding the life, work, and death of Stefan Zweig, a Vienna writer whose reputation is now on its way back up, Oliver Matuschek’s biography and George Prochnik’s elegant reflections on exile provide excellent entry points.

Suggested Reading

Taking Responsibility: A Rejoinder

Between rabbinic rulings and public policy: a response from Daniel Goldman and Yossi Shain and a rejoinder from Yehoshua Pfeffer.

No Empty Place

The most substantial theoretical response to Hasidism from a leader of the mitnagdic—literally, opposition—movement did not appear until 1824, three years after the passing of its author, Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin.

A Journey Through French Anti-Semitism

There is a problem with the inevitable reflexive warnings after every vicious attack not to slip into Islamophobia. A short personal history of how France got here.

Bling and Beauty: Jerusalem at the Met

In a new exhibit at the Met curators Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb wear their liberal hearts on their sleeves, imagining that Jerusalem's crowds might yet be resurrected as a convivial medieval pluralism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In