Hope, Beauty, and Bus Lanes in Tel Aviv

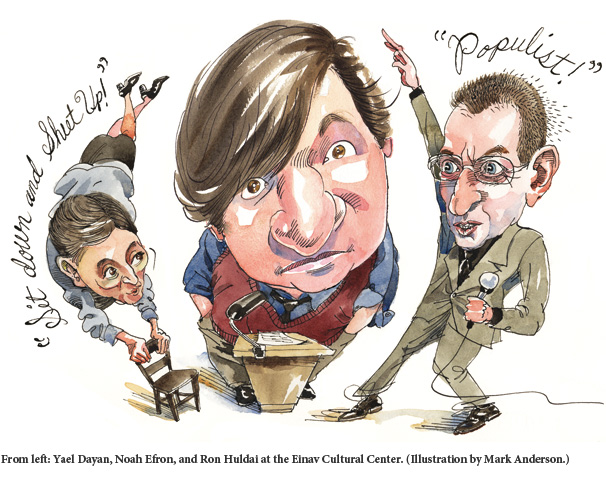

I‘m standing behind a Brazilian oak dais in the Einav Cultural Center rotunda, where the Tel Aviv-Jaffa City Council meets monthly, speechifying for priority bus lanes. The council chairwoman, Yael Dayan, sits to my right, admonishing me, in her harsh smoker’s growl, to shut up and sit down. The mayor, Ron Huldai, sits to my left, scolding in a stage whisper: “You are a disgrace. I expected integrity from a university professor but you have none. You bring shame to your profession, your family, your city. You have no honesty; you are a populist, a demagogue.” I keep my eyes pinned to the text of my speech, but stumble on the words. My tongue is fat and my mouth dry. I am frantic and exhausted, and running through my mind is, “I’m being trash-talked by the mayor of Tel Aviv . . .” and then, with self-pity, “How did I ever get here?”

This wasn’t the first time I asked myself that question. Twenty-six years ago, fresh out of Swarthmore College, I enlisted in the Israeli infantry and three months later found myself trudging through Sidon, Lebanon at dusk, carrying a gun I could barely shoot, following orders in a language I could scarcely speak, in a war I could hardly understand for a cause I could hardly remember. All at once nothing around me, nothing in the life I had only just then chosen for myself, made any sense to me anymore. “How did I ever get here?” I said on that first night over the border, my breath fogging the frigid December air.

These two stories bracket my adult life. What brought me to Israel in 1983 was politics, or some fancy notion of it that I’d gotten in college. I was desperate to wrench myself from the predictable path I was on—another American Jew destined to be professor of something somewhere—and I knew that to remake myself I needed to be elsewhere. People make their societies, I figured, and societies make their people. Athenians made Athens, Aristotle had written, and Athens made Athenians. Israel was a place that I could mold, and it was a place I reckoned I wouldn’t mind being molded by. The earliest Jewish pioneers to Palestine had a slogan for this: Anu banu Artza li-vnot u-lehibanot bah (“We’ve come to the Land to build and be built by it”). I joined a group moving to Israel from the United States that described its aims in a pamphlet mimeographed onto card stock:

These two stories bracket my adult life. What brought me to Israel in 1983 was politics, or some fancy notion of it that I’d gotten in college. I was desperate to wrench myself from the predictable path I was on—another American Jew destined to be professor of something somewhere—and I knew that to remake myself I needed to be elsewhere. People make their societies, I figured, and societies make their people. Athenians made Athens, Aristotle had written, and Athens made Athenians. Israel was a place that I could mold, and it was a place I reckoned I wouldn’t mind being molded by. The earliest Jewish pioneers to Palestine had a slogan for this: Anu banu Artza li-vnot u-lehibanot bah (“We’ve come to the Land to build and be built by it”). I joined a group moving to Israel from the United States that described its aims in a pamphlet mimeographed onto card stock:

Moving away from the fragmentation of western urban society, we hope to weave our lives into an integrated whole . . . Of course, socialism is basic to us . . . We want to be actively involved in our region of Israel. From the day we arrive we want to be in contact with our neighbors—other settlements, development towns, Arab villages, cities—we do not want to be islands unto ourselves . . . We will become different people. Our children will grow up differently.

The sweet and earnest cluelessness of this pricks my heart, as when my daughter, at the age of 3, declared her intention to marry my wife and live with us forever. It is easy to see now that I took myself too seriously, misunderstood how things work, and overestimated my talents and the plasticity of my character. Still, in 1982 there were reasons for me to believe I could leave an imprint on Israel in a way that I could not in America. Israel then seemed less than fully formed. Only sixteen years had passed since the Six-Day War, nine since the Yom Kippur War, and four since the Camp David Accords brought peace with Egypt and the evacuation of Sinai. Settlements in the West Bank and Gaza were still new and small; so too was “Peace Now.” Like Greenwich Village in the 1930s, the country seemed small. In my first six months in Israel, I met the famous philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz, the famous novelist Chaim Gouri, the famous politician Luba Eliav, and the famous kibbutz historian Muki Tzur. I studied Midrash with Ari Elon, whose father was a justice on the Supreme Court. It seemed that everyone in the whole country was just an Egged-bus ride away.

What’s more, the atmosphere was improvisational. If other armies are regimented, Israel’s had a seat-of-the-pants ad hocness to it. Ehud Barak’s early fame was owed to a stunt in which he cruised through Beirut in the front seat of a Mercedes wearing a woman’s wig, arriving safely to assassinate a thug behind the 1972 Munich Olympic murders in his home. On Tel Aviv’s streets, one still saw horse-drawn carts, Czech motorcycles with sidecars, boxy three-wheeled cars made out of fiberglass, motorized bikes, and homemade hybrids that teased the imagination. Television had only come to the country in 1966, and color television not until 1980. Just after I arrived, Jonathan Miller, a kid I’d known growing up, new to the country like me, made it as a musician, appearing on television and filling big halls. His band came to perform for my unit in basic training. In Israel of the early 1980s, everything from sedans to sitcoms to celebrities was provisional and open to redefinition. So, at least, it seemed to me. And then it didn’t.

Soon after I arrived I stopped believing that I could much change the country, or that the country could much change me. I retreated from all that had brought me here, including the hope of being a different person than I would have been in America. I quit the kibbutz to which I’d moved, and enrolled in a Ph.D. program in hopes of becoming a professor of something somewhere. I became as cynical and alienated and self-righteous about politics as any grad student in John Lennon glasses reading Chomsky in the Hungarian Pastry Shop in Morningside Heights. This, I now can see, was my true acculturation, as there is nothing so Israeli as withering pessimism about Israel itself, and lacerating self-criticism. I perfected my Tel Aviv sigh, a prêt-a-porter reply to each new political outrage, equal parts exasperation, desperation, and resignation.

As all this was going on, disillusionment with politics and politicians has flourished. For the past three elections, a popular bumper sticker has read “Mushchatim, nimastem!“—roughly an amalgam of “You Crooks Disgust Us!” and “Throw the bums out!”—and it captures a prevailing mood. In the past decade alone, two Presidents (Ezer Weizman and Moshe Katsav) and one Prime Minister (Ehud Olmert) have resigned under criminal investigation. The son and campaign manager of a Prime Minister (Omri Sharon) has gone to prison, as have a Finance Minister (Avraham Hirschson) and a Labor and Welfare Minister (Shlomo Benizri). Today’s Foreign Minister (Avigdor Lieberman) stands accused of bribe-taking, fraud, and money laundering. Political office has come to be seen by many as a sinecure for the debauched and debased.

Recently, though, I’ve lost my talent for anguish about Israel, and for despair. Perhaps this is the result of some perverse mid-life crisis, in which my decades of fashionable ennui suddenly seem like time poorly spent. Maybe it has something to do with seeing my kids grow up unmistakably Israeli and unmistakably beautiful. Part of it, certainly, is the dawning realization that in truth we are not a nation in decline. While some things have gotten worse since I arrived here almost thirty years ago, others have gotten better, and sometimes the retreat and advance are linked. Israeli politicians are indicted these days at a rate without precedent, yes, but this fact owes more to rapidly rising standards of accountability for public servants than it does to rapidly declining moral standards among politicians themselves.

Once one is willing to see them, there are, in fact, many indications that in politics here there are more possibilities and opportunities than conventional wisdom allows, and reasons for hope that, in time, problems that now seem intractable will find resolution. Some are large and some are small, little more than anecdotes. In May 2003, for example, three hundred Israeli Arabs and Jews traveled together to Auschwitz-Birkenau where they tearfully intoned a long list of names of Jews murdered on that spot by Nazis. The organizers, a priest named Emil Shufani and a journalist named Nazir Magally, both of Nazereth, explained that their purpose was to expand their own spirits by coming to understand firsthand the depths of Jewish suffering and the source of many Jewish fears. What is most remarkable about this trip is that, by conventional wisdom, it could not have taken place at all. It finds no place in the standard story, rehearsed in most mornings’ newspaper, in which the ability of Jews and Palestinians to regard one another with empathy is vanishing. Much else also belies the dystopic tale of Israeli decline. When my wife first sought an OB/GYN residency in Tel Aviv in the 1980s, she was turned down on the grounds that it was unwise for women to treat women, as they lacked the natural objectivity needed to do so. (She completed her residency in Boston.) Now, most OB/GYNs in Israel are women, a small fact that reflects a grand improvement in the lives of women here. In stark contrast to its portrayal abroad, Israel has become a gentler, more decent place for almost everyone within its borders. No matter what bad things are noisily happening here, alongside them are quiet things, easily overlooked and surely good.

This is also what I have seen in local politics. Running for City Council, I spent two months doing what aspiring local politicians do: trudging door to door, shaking hands, speaking and listening to city residents. By election night, I’d sat in 1,500 living rooms, balancing a glass of water on my knees, discussing politics. People told me with feeling how their schools could be improved; how neighborhood bomb shelters could be rehabbed into art centers for kids; how Arab kids from Jaffa and Jewish kids from Tel Aviv could be encouraged to know and trust one another; how medical care could be extended to refugees from Eritrea and Sudan; how composting could be promoted; how bus lines could be improved; how food could be supplied to the poor discreetly, so as not to embarrass; how free performances of Molière in the park could improve literacy. The high voltage goodness and generosity of spirit in those living rooms finally jolted me out of thirty years of fashionable pessimism about Israel and its possibilities.

Running for the Tel Aviv-Jaffa City Council was an act of hope, and serving has been a source of hope. It reminds me that the obdurate issues of the settlements and Hamas and the rest, though they are matters of life and death, produce a distorted image of Israel and of our politics when considered in isolation. For most of the past year, I’ve been agitating to get the mayor to build a network of fast, cheap busses with their own lanes, high-tech ticketing, and GPS that changes the traffic signals as they approach. Thousands have joined the campaign, and lobbying has won us the support of the Ministry of Transportation. If it now takes an hour and a quarter for a single mother in Jaffa to get to and from classes at the university, once we’ve got our bus system in place, it’ll take her twenty minutes.

In crusading for these busses, I am finally planting my olive tree in this soil. I am saying, along with many others, that I believe in the future of this place, that I believe that one day will lead to the next, and that we can make this city, this country, better. Amidst the sturm und drang of geopolitics, quotidian life continues and, in its way, it is beautiful.

It is easy to forget how little time has passed since Israel was established, how new this place is, how recent the vintage of its successes and its failures. It is easy to forget that the father of Yael Dayan, the woman who reproached me at the dais, was Moshe Dayan, a general who executed wars and negotiated an historic peace with Egypt, and that his parents Shmuel and Devorah Dayan were founders of Nahalal, the first collectivist moshav in Palestine. It is easy to forget that the parents of Mayor Ron Huldai, who talked trash as I stuttered about my busses, were Ozer and Henke Huldai, who helped establish Kibbutz Hulda after moving to Palestine from Lodz. Millions have lived and died in a century and a quarter of Zionist history, and many have suffered in many ways. But equally, many have awakened to the suffering of others as well as our own. Golda Meir’s casual dismissal of Palestinian aspirations was shared by almost all Israelis only forty years ago, yet it finds little echo in today’s Israel, not on the right or the left. As I write, young Israelis who could be working in high-tech are tutoring kids in the run-down part of town, living in cheap apartments furnished from the street. Israel’s history is a blip, and though too many of us complain that it is static, in fact, it has never stopped moving. Rather than suggesting fixed and irrevocable decline, the arc of this short history suggests that there remain many possibilities still unrealized.

When I think of Israeli Muslims, Christians, and Jews weeping together on the railroad platform of Auschwitz, or when I remember the woman two blocks from my apartment gathering canned goods from her neighbors to deliver to poor families in Jaffa, I conclude that my old cynicism was a sucker’s fancy. Hope is a better bet. I find myself believing that, with time, in Tel Aviv-Jaffa, we’ll even get our priority bus lanes.

Suggested Reading

Thinking About Revolution and Democracy in the Middle East: A Symposium

Since January of this year, revolution has spread across North Africa and the Middle East with such velocity that predicting exactly what will happen next is probably a fool's errand. In this issue, we have asked seven writers to return to their bookshelves and tell us what books, authors, and arguments they find helpful in thinking through the causes and implications of these surprising events.

Nobody Expects

I mug at myself in the mirror and recite the old Monty Python gag.

Lessons of the Soviet Jewish Exodus

Between the mid-1960s and 1991, more than two million Jews left the USSR. To the extent that the Soviet Jewish exodus is remembered, its lessons are misunderstood.

Love, Counter-Historical Style

Love letters to Israel, Judaism, and each other from Rachel and David Biale.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In