Nobody Expects

Here’s what I thought was in store for me as I grew old: I’d stay clear, strong, and energized through my eighties, keep writing stories, and then I’d slow down and my heart would begin to give out, a stammering motor catching, stumbling, dimming—sunlight blocked by cloud—and there’d be a time when I’d say goodbye, goodbye to wife and children and friends, and then rational consciousness would slip away, I’d fade into oblivion or, better, be enfolded into radiance, the radiance that emanates through all the worlds, and I, barely I anymore, would feel the diffusion of my individual light as it spread and spread.

But no, it turns out, no, that’s not what’s in store. For in my early eighties, Parkinson’s disease has settled on me, a vulture. It followed upon a terrible case of shingles. There’s no cure. This is the beginning. The Parkinson’s won’t kill me—I keep getting told this, as if it should comfort me. It won’t kill me—but it has already submerged my life. I shake, I tremble. I have a hard time swallowing. So, I drool. Have begun to stumble. Ah, but that’s the least of it. Worse, I become exhausted, wake exhausted, nap often. I’m usually half-asleep. If I take a pill, I can obtain an hour of writing—slow, muddy writing on my laptop.

And maybe still worse, when I speak with friends or in a group—a book group, a political group—it often feels as if my brain is under water. Everything slows, slows. I reach for an idea like a stutterer reaching for a word, struggling to enunciate a word, but it has disappeared. My mind feels sluggish, thick, yet empty, blank. There’s silence in the room. The group, uncomfortable but wanting to help, waits, kindly giving me time. I can feel their encouragement. I finally come up with a reduced version of my idea, lacking specifics, spoken in a guttural croaking. A frog speaks.

All my adult life I’ve had the ability to manipulate categories, play with the nuances of texts. Now I’m afraid, and with good reason, that I’ll have nothing to say. If I write down an idea, I’m able to read it aloud and speak with the old intelligence. But I forget the names of scholars, the titles of books or films. My analytical abilities, my understanding, remain. For now. But I’ve become unsure about everything. Have I been punished because I’ve often been intellectually arrogant? Paid back for being a fool? I don’t believe the world works that way—that God works that way.

But who knows how the world works? How God works? “And though worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God”—what can that mean? My body is already being destroyed.

But early one morning, I stop in the middle of morning prayers, and, in a moment of insight—or perhaps its opposite, delusion—decide that, in a sense, I’m in a place I’ve never heard anyone describe: both alive and not alive. Like a kind of ghost, I can look from a distance upon my children, my wife, our friends—and love those I look upon. For a year or—God forbid—ten years, I’ll be an observer. Standing far outside, above the living world. Not hiding away in shame. I’ll still visit my children, I’ll still eat—though ghosts don’t eat so very much—still cook with pleasure, still read books, though not so fluently; maybe even write stories, as I’ve done all my life, though now with more difficulty than I’ve ever faced. But secretly, inwardly, I’ll be separate, taking in the world without acting in it.

It’s foolish to strive. Saul Bellow’s Augie March tells us, When striving stops, the truth comes as a gift. A ghost’s truth: nothing at stake. I offer no resistance, claim nothing, take no solid position, let the food fall off my fork. I cope on my own. Ghosts don’t join together for mutual support. My whole adult life I’ve been firm; if anything, too firm. Now I’m permeable. Nothing to battle against; no expectation of a miracle cure. If you’re lucky it gets worse more slowly.

I exercise hard, I stretch. I take time to notice and to love—maybe because as a ghost I don’t put myself in the way. I love more, not less. My love surprises me. I sleep badly and there are mornings when I groan. By noon I’m usually in the mode of ghostly acceptance.

I don’t expect a lot; my friends and family don’t expect a lot from me. I wonder if they see the love, for my face has stiffened, I’m told, into a “mask,” the frozen face of Parkinson’s. I never expected to have a frozen face. With effort, I can smile fully, with eyes and cheeks and mouth. But to do so feels dishonest, mugging for a camera.

A ghost? But please!—who do I think I’m kidding? Some ghost! Do ghosts drool? Oh, I’d like to talk myself into seeing my disease not as deterioration but as an opportunity for spiritual growth. But isn’t it self-deception to pretend I’m lucky to stumble along—it’s striving just to get myself up in the morning. I’m no ghost. To pray morning prayers is a struggle. I strap on tefillin and mumble words of gratitude and awe and try to feel connected with the One. But fatigue fills me. I’ve always believed that you find your deepest life not by getting rid of difficulties, not by asking everything to go smoothly, but by sailing your hardship through difficult seas. The seas will change you, will make you a sailor. And now? And now?

I mug at myself in a mirror, recite Monty Python’s old gag in which a character complains at being questioned, saying, “I didn’t expect a kind of Spanish Inquisition.” In bursts Michael Palin in 16th-century red cape, and sneers, “Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.”

Every morning my first prayer, Modeh ani, offers thanks to God for awakening my soul once again; great is your faithfulness. Awakening my body out of the dark of sleep, awakening my spirit to the things of this world, things that, seen in a holy light, become holy.

I can walk, thank God. Every long stride feels like a victory. And I can see, I can hear. But more easily I focus on the damage; gratitude is something I have to manufacture—it doesn’t come without effort. Is this gratitude a way of deceiving myself, a way of pretending to compensate for what’s lost, broken, and irreparable? There are ways of holding back the growth of symptoms: exercises for developing balance and strength. And what about the pills? They work a little—until they don’t. There’s no way I can fight my way back to clarity of mind and full wakefulness. The more I fight, the less good I’ll take from this. Any victory of spirit has to come from not whining and not struggling.

I am an old man, wanting to stay comfortable till I die. Yet knowing that unless I give myself up to the unknown, I might as well die right now. How am I going to make use of this time? That’s not the right question. To say “make use of” is to think you’re in control; I need to relinquish control.

I was riding the trolley—a streetcar we called it—down Broadway, Upper West Side, from my classes at Columbia College, riding the old Broadway trolley—so you can imagine how long ago this was, the 1950s, when there were still trolleys in Manhattan. Rocking cross street to cross street, it jingled to warn cars crossing the tracks. I remember a sunny day. Afternoon sun going down over the other side of the Hudson slanted on every block between the buildings. I sat on the hard rattan seat looking down at my book as we jogged along.

I wasn’t paying attention. What I tell you about the sun or about the stiff rattan seats is true, but frankly, I have to reconstruct it after the fact. I was oblivious then.

I began to be aware of a conversation going on next to me. A distinguished older man in jacket and tie was exchanging words with a well-dressed woman, same age, maybe 60, maybe 70. He tipped his fedora. He stood up, she sat down in his place, and they commenced to talk about the “younger generation.” To talk about me—isn’t it a shame, young people nowadays.

“Do they think to give you a seat? How were they brought up?”

“They just sit—just sit and watch you stand.”

“They must think they’re privileged.”

They spoke loudly, so I would hear and take shame. It wasn’t fair! I had been in the world of my book. Usually, in fact, I made it a point to offer my seat. Nevertheless, I swallowed the shame, carried it block after block as they entertained themselves talking about me. If I’d been older, I’d have entered the conversation, laughed at my own impoliteness, apologized. But I’d waited too long. And I was too young and too mortified. They were old—white hair and wrinkles, probably full of aches and pains.

I waited for my stop at 86th Street, and then my strategy came to me as I put the book in my bookbag. When the streetcar slowed, I got up and, blank of face, I played the gimp, the poor cripple, played it as if I were trying to avoid playing it, limping, limping, limping down the aisle, not looking back, careful not to exaggerate, one shoulder just a little higher than the other, grasping seat backs and poles, and then, when the door opened, I made my painful way down the steps and out the trolley. And when I crossed to the sidewalk I kept limping until the streetcar was well down the tracks, so that if they saw me, the old people, even a block away, they’d see a cripple, a poor cripple boy they’d bad-mouthed. I was elated.

I can imagine walking down the aisle not of a trolley but of a rocking subway or bus, slightly blank of face from the Parkinson’s, stiff, needing to hold on. And now those old people, long dead, watch me walk. Ghosts. “Not so funny now, is it,” one of them says.

I pray for equanimity. I want to acknowledge my sickness with equanimity. But I don’t want to lie. This long diminishment may, I pray, be a blessing. The trivial is discarded, shrugged off, the ordinary and everyday accrue meaning, even beauty. It’s not just the Spanish Inquisition that’s not expected. God is here, woven into the contradictions. Into the gap that takes the breath away.

Love can be a distillate of growing old. And I’ve loved my wife (you, Sharon) more and more, loved the children more and more. Yes, we deepen. But, oh my God, what we pay for the deepening.

Who expects life in the form it arrives? The Spanish Inquisition knocks at the door. All my life the inquisitor has been waiting to burst in. Who knew? Now he enters with his case full of instruments.

It’s three o’clock in the morning. Aches and pains have replaced sleep. My right calf wakes me in nasty spasm. At the same time, because my throat constricts from the Parkinson’s, I have to work to get down the pills I take for Mr. Parkinson, pills for said aches and pains. “Said aches and pains.” I hear my language trying to make this a laughing matter. As if words could change things. I sigh: I watch my fingers shake. Oy! That oy of Yiddishkeit tries to handle pain with humor. Whadaya think, chump? You expect the physical laws of the universe to be revoked just for you? What chutzpah! But how funny is it, somebody tell me, please, when you have to descend the stairs right foot down to the next step, left plays catch-up, right foot down again? It’s no laughing matter, as my mother used to say.

Still, this oy, this mode of handling suffering can maybe be something of a help. Why? Because implied self-deprecation sets you slightly apart from the pains. You split yourself, make fun of the complainer. And the word, pains, the plural, makes light—as against the singular, pain. Pains can be funny; pain can’t. Funny as a crutch.

From one to ten, how much pain are we dealing with here? Not a lot. Nothing to do with the Parkinson’s. Let’s call it a five point three, ladies and gentlemen. Aach. Not so terrible; but not all that funny. And now, three-fifteen in the morning, the cramp melts, the calf relaxes, and the old guy can stumble out of bed, foot to the floor, other foot to the floor. Can he stick the landing?—and yes! Yes he can. Let’s give said old guy a round of applause.

Uncertain legs carry me to the bathroom, back to bed again, where my wife Sharon stirs.

“You okay?” she murmurs. “What’s the matter?”

“Who said anything’s the matter?”

“You groaned. Goodnight, then,” she says, and turns over, already asleep. Her sleep comforts my wakefulness. And I keep vigil till the morning light makes distinct the dresser, the bedside tables, my slippers under the window. Once I get myself up for the day and exercise, and my pills have had time to work, time for the pain, deep sluggishness, and exhaustion to diminish, time for the tremors to quiet, I’ve got it beat for the morning. My job now is to keep Parkinson’s from becoming the totality of my day.

Have you ever seen a dog trotting sprightly on three legs, maybe one lost to a truck? He may have whined from pain when he was kept from licking at the wound by an uncomfortable lampshade collar, but now that the collar’s off, he adjusts to the new condition as if there were no loss—it’s the way I am. A dog will mourn for a lost master or for the loss of another dog in the same household, but not for a lost leg. He doesn’t seem to experience the contrast between now and before. Let me become like a three-legged dog.

What should I make of this life? I make, have always made, words.

I’d like to be brave, like to be cavalier—at least pretend to myself to be cavalier. But again and again I fall into monitoring my losses and my potential losses, as if I were my own banker. It’s a bum investment. I might as well live it up, turn spendthrift, prodigal, profligate—very nice. Very nice. See if you can fool yourself with words.

We all know the way we’re supposed to respond to a sickness such as Parkinson’s. So that at the memorial service a eulogist can say, “He fought his sickness, but he never complained. He was kind and generous. He expressed gratitude for the life given him.” But I’m not going to fake it in order to rate a decent eulogy.

Dear God, help me accept what’s coming to me. Help me join what’s coming as to the strange music of a dance. I want to dance to the new music. You, coming through the ballroom door, teach me to dance. Be my partner in the dance.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Dirty Hands in Difficult Times

Israel's relationship with apartheid South Africa is an inconvenient—perhaps unavoidable—truth.

The Life of the Flying Aperçu

Dickstein’s story is not a narrative of apostasy and rebellion; belief and doctrine play a minor role.

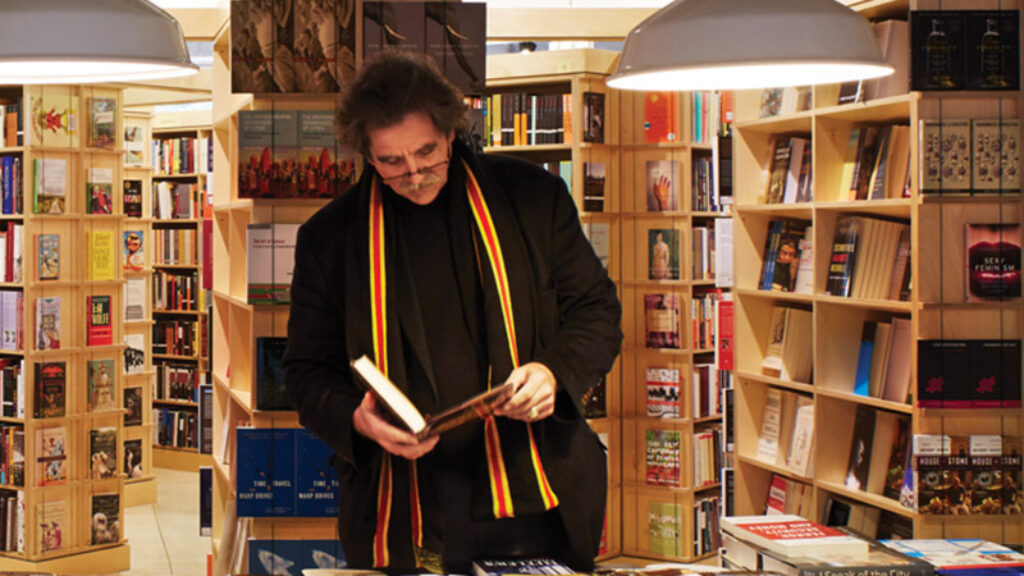

Bookstore or Beis Medresh

How I learned to stop worrying and love to browse.

Questioning in the Darkness

A century ago, S. Ansky (Shloyme-Zanvl Rappoport) assembled thousands of questions for a survey directed at shtetl residents in the Russian Empire's Pale of Settlement. A new book examines this fascinating survey.

Robert Rockaway

Parkinsons is an awful affliction. I have often thought about the Jewish physicians and researchers that Hitler murdered. So many of them were on the cutting edge of medical research. If the Holocaust would not have happened, I like to believe they would have found a cure for Parkinsons and other diseases that plague mankind. Hopefully a cure will be found, and soon.