Letters, Winter 2011

God, Torah, and Israel: An Exchange

Rabbi Daniel Landes’ da’ mah she-tashiv (“Know what to answer the heretic”) approach to my Radical Judaism, protecting innocents from “the dangers lurking in the rhetoric that Green and like-minded thinkers employ,” represents a theological bankruptcy lurking in traditional Jewish circles. The forces of religion fought two great battles in the 20th century, one against evolution and the other, taken more seriously by Jews, against biblical criticism. It lost them both, quite decisively. These defeats, plus the Holocaust, are real parts of the baggage that any intellectually honest Jewish theology must confront. My book is an attempt to create a viable Judaism in the face of those realities. Landes may choose to live in a closed circle that pretends these uncomfortable facts do not exist, continuing to play by the old theological rules. For Jews living outside those circles, such an approach does not work. He should know; many of his students are among them.

Who is the “God of Israel” Landes is so proud to champion? The God of Numbers 31, telling Moses to slaughter the Midianites? The “compassionate Father” of our rabbinic prayers? Would Landes accept the God of Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed as “the God of Israel?” Or the God of the Zohar? The longest single chapter of my book is precisely about the evolution of our understanding of God, a process that has never ended. Landes passes over the obvious evolution and variety of Jewish views of God as though they did not exist. But a freezing of theological thought in the face of contemporary challenges is precisely what we do not need. It is just as threatening to living Judaism as is the freezing of halakha.

Indeed Mordecai Kaplan understood that much of Judaism’s vigor lay in its ability to grow and evolve. But so did Rav Kook, whose theological writing has always attracted me more than Kaplan’s. I am amused that Landes finds Kaplan to be my “hidden master” at this late point in my career. Where was he when I could have used him to shore up my Kaplanian credentials? While Kaplan’s style may at times be trying, to dismiss his theology as simply “boring” is beneath the dignity of response. Kaplan at least tells you openly and honestly what he means by “God.” I respect this and try to do the same. In some areas the divergence between us may be more in affect than in substance. But in matters of the heart that makes all the difference.

The nasty attack on Jewish Renewal is also unworthy of Landes. He picks out my comment on the seventh commandment (I say clearly that I am reading the ten as a guide for teachers) to remind his readers of the sexual misdeeds of some leaders in that movement. I suggest he beware of calling the kettle black. I have not seen that the high fences of halakha have been terribly successful of late at helping some Orthodox teachers to defeat temptation, either sexual or financial.

The high point of my annoyance is Landes’ claim that I offer “no doctrine of ahavat Yisrael [love of the people Israel],” This book is written entirely in the spirit of love for both Judaism and Jews. Why else would I make the effort? Landes is unhappy that I admit openly my deep alienation from “the narrowly and triumphally religious” within our community.

Honesty can sting. My claim to be “a religious Jew but a secular Zionist” is also intentionally distorted for polemical purposes. I meant simply that I remain committed to the vision of a Jewish and democratic state (there—I have signed my loyalty oath!) while according it no messianic significance. Has that gotten too hard to understand?

Landes lines up with the late Sam Dresner and others in expressing an overweening fear of anything that smacks of pantheism, celebrating God within nature, or an underlying sense of universal religiosity. But it is precisely this sort of religion that I believe humanity most urgently needs in this century, when our collective survival as a species is so threatened. I am here to teach a Jewish version of it, one relying deeply on our own sources and bearing our values, but without making an exclusive truth claim for Judaism. I rejoice that the deepest religious truths are known to men and women of many cultures, clothed in the garments of both east and west. See Malachi 1:11.

Mostly I am saddened and disappointed that Landes reads me this way. He is, after all, the director of Pardes Institute. Surely that worthy institution was so-named by its founders for the association of pardes (orchard) with the multiple ways in which Jewish sources can be read and interpreted. It has claimed for decades to champion intellectual pluralism under the cloak of behavioral conformity. Heresy hunting does not befit its leader.

Arthur Green

Rector and Professor

Hebrew College Rabbinical School

Boston, MA

Daniel Landes Responds:

According to Arthur Green, “the story of evolution, including the ongoing evolution of humanity, is bigger than all the distinctions between religions and their myths.” But he struggles to find meaning within this cold process. In Radical Judaism, he writes:

If we could learn to view our biohistory this way, the incredible grandeur of the evolutionary journey would immediately unfold before us. We Jews revere the memory of one Nahshon ben Aminadav, the first person to step into the Sea of Reeds . . . What courage! But what about the courage of the first creature ever to emerge from sea onto dry land? Do we appreciate the magnificence of that moment? [emphasis in the original]

Let’s set aside the question of whether this is a sophisticated way to think about evolutionary history (it isn’t), and note how quick Green is to personify nature. Perhaps it is because his God (like Mordecai Kaplan’s) has been divested of all personality.

Green asks rhetorically whether I would accept the God of Maimonides’ Guide or of the Zohar. They are, of course, two radically different conceptions, but both assert a divine transcendence that Green flatly denies and grapple with the problem of divine-human interaction. I understand Green’s fascination with Rav Kook, a true panentheist, but underlying Rav Kook’s theology is the shimmering energy of the All-existing within God. As the ground of being, God validates and uplifts nature. Kook’s God is neither dead nor asleep: He is free to plunge into life and history.

In short, Green is right to point out that the tradition of Jewish thinking about God has a history, but, as he acknowledges, he has given up playing by the “old theological rules” of this tradition. Why, then, all the righteous indignation when a reviewer points out that this is precisely what he is doing? His disdain is also hard to understand. The relational God of Israel is, after all, the one affirmed by his teacher Abraham J. Heschel as well as by Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter, the Gerrer Rebbe, author of the Sefat Emet and another key figure for Green. As for the fish, all I can say is that, given Green’s neo-Hasidism, I hope that at least it was a herring or nice sable.

Green writes that the “high point of his annoyance” with me is in my contention that he presents a theology that has no doctrine of ahavat Yisrael, and then goes on to assert that he loves Jews and supports the State of Israel. I never asked for a loyalty oath or doubted Green’s love of his fellow Jew. But neither of these adds up to a doctrine. In his book it would appear that he would replace simple Jews—if they have the wrong politics or a backward spirituality—with a member of Green’s “extended faith community” (“my Israel”) who is not Jewish but who shares his journey. My point was that ahavat Yisrael is about empirical (one might almost say carnal) Jews, an actual living community. But ahavat Yisrael also cuts both ways. Tradition leads me to maintain—as difficult as it might be to fathom from these exchanges—that Green and I are inextricably bound to (and stuck with) each other.

When I invited Green to lecture here at Pardes, the discussion in our beit midrash was frank and vigorous, but there was nothing that smacked of censure. Similarly, in my review, I argued that he was deeply, theologically wrong, but Green’s letter notwithstanding I did not call him a heretic (a word I don’t use). Pluralism does not preclude criticism.

Finally, I owe Green an apology. He is, of course, right that the Renewal movement is not the only one that has been beset by sexual scandal, and I did not mean to suggest otherwise. I hope that the Orthodox world has at least begun to learn that denial serves no one well, and that the “high walls of halakha” are sometimes breached by those who ought to maintain them. I suggest that the Renewal movement might learn, nonetheless, of the indispensability of law in curbing human temptation.

Suggested Reading

A Novel of Unbelief

Religion, faith, and the search for tenure at Harvard underpin a comic novel by Rebecca Newberger Goldstein.

Jerusalem of the Balkans

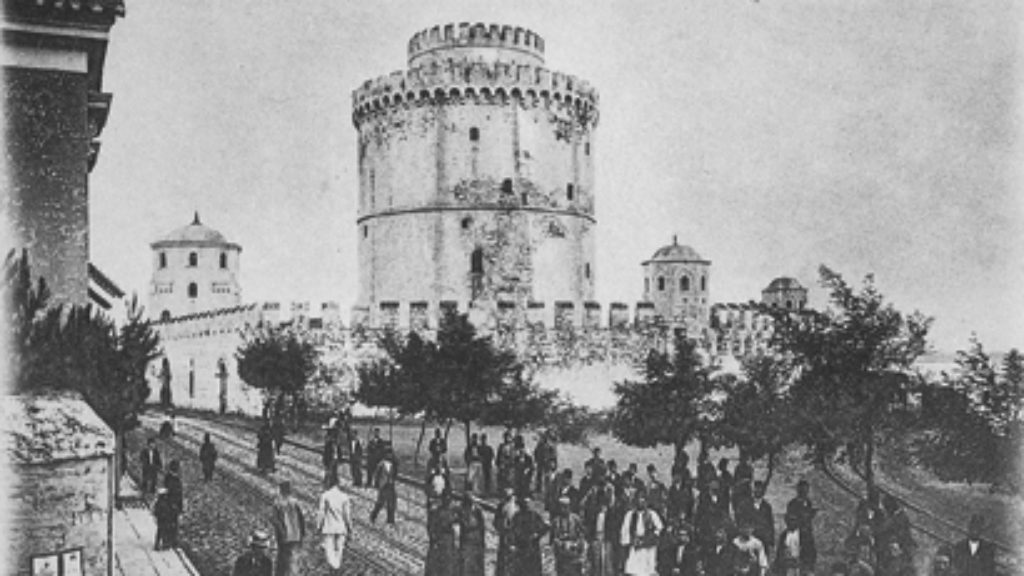

In 1911, David Ben-Gurion spent several months in Salonica and declared that it was "the only Jewish labor city in the world." Now, because of an open-minded mayor and his nationalist opponents, this formerly Jewish city is experiencing a peculiar mix of Jewish memory and anti-Semitism.

Eichmann, Arendt, and “The Banality of Evil”

Richard Wolin’s review of a new book about Adolf Eichmann caused a stir, mainly about Arendt. His exchange with Seyla Benhabib on the banality (or not) of evil.

Starving for Zion

For Chaim Gans, the justification for nationalism in general, and Zionism in particular, lies in the human rights of the individual.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In