Shifting Sands

Shlomo Sand is, by now, probably the best-known anti-Israel Israeli intellectual. Born in 1946 in a DP camp in Austria to Holocaust survivors, Sand is a professor of history at Tel Aviv University. He believes, following theorists such as Benedict Anderson, that nations are, in the nature of the case, modern inventions, and that Israel is a particularly bad one.

How I Stopped Being a Jew is Sand’s most recent (and shortest) book on this general theme. He burst upon the ideological scene a few years ago with The Invention of the Jewish People, quickly followed by The Invention of the Land of Israel: From Holy Land to Homeland. These earlier books are fairly elaborate deconstructions in which the Jewish people turn out to be a figment of the imagination and the connection of the Jews to the Land of Israel (ahavat yisrael) a myth. In the first book, Sand rehashed an old and discredited theory that Ashkenazi Jews are descendants of the Khazars, who are said to have converted to Judaism and created an empire in the Caucasus in the 8th century. The Khazar theory was refuted yet again by several distinguished historians who reviewed the book in Israel, Europe, and America (it became a widely translated best-seller), but of course both the motivation and the wide appeal of Sand’s arguments lie elsewhere, a subject to which I shall return. (Incidentally, Sand’s academic expertise also lies elsewhere: He is an expert on the work of the radical 20th-century French thinker Georges Sorel.)

Even if Sand’s historical argument about the history and makeup of world Jewry were correct (he’d also like to trace much of North African Jewry back to Berber tribes, diminishes the history of ancient Israel at every turn, and so on), would it make a difference? In a classic essay about the biblical Moses, Ahad Ha’am, the father of cultural Zionism, reflected upon history and historical truth:

And so when I read the Haggadah on the eve of Passover, and the spirit of Moses the son of Amram . . . who stands like a pillar of light on the threshold of our history, hovers before me and lifts me out of this nether world, I am quite oblivious to all the doubts and questions propounded by non-Jewish critics. I care not whether this man Moses really existed; whether his life and his activity really corresponded to our traditional account of him; whether he was really the savior of Israel and gave his people the Law in the form in which it is preserved among us; and so forth. I have one short and simple answer for all these conundrums. This Moses, I say, this man of old time, whose existence and character you are trying to elucidate, matters to nobody except to scholars like you. We have another Moses of our own, whose image has been enshrined in the hearts of the Jewish people for generations, and whose influence on our national life has never ceased from ancient times till the present day. For even if you succeeded in demonstrating conclusively that the man Moses never existed . . . you would not thereby detract one jot from the historical reality of the ideal Moses—the Moses who has been our leader not only for forty years in the wilderness of Sinai, but for thousands of years in all the wildernesses in which we have wandered since the Exodus.

In short, it was, in part, precisely through the image of Moses and other shared figures, stories, authoritative texts, ideas, and rituals that the people of Israel—which is what they called themselves—sustained themselves in exile, or galut—which is what they called it.

A little later in the essay Ahad Ha’am writes: “And it is not only the existence of this Moses that is clear and indisputable to me. His character is equally plain, and is not liable to be altered by any archeological discovery. This ideal—I reason—has been created in the spirit of the Jewish people; and the creator creates in his own image.” He understood as well as Shlomo Sand (or better) how all peoples invent and sustain themselves, but he also understood that the Jewish people had been doing it for a very long time. Sand, of course, grants the reality of pre-modern Jewish religion, but he takes a very narrow and peculiarly modern idea of what a religion is, and he seeks repeatedly and implausibly to sever it completely from both Zionism and Israel.

Does Sand really believe what he writes? He himself participated in one of the most unusual social events of the second half of the 20th century: the kibbutz galuyot, the meeting in Palestine—later Israel—of millions of Jews from different parts of the world and their amalgamation into a new Jewish society and successful nation state. There were huge cultural differences among these diverse Jewish groups. In looks, language, traditions, occupations, social structures, and relations with their non-Jewish environments, a Jew from Russia and a Jew from, say, Yemen had little in common. Nonetheless, they found the inner resources to establish a state, to live together, to intermarry, and to develop a modern country where most of the inhabitants now seem content—Shlomo Sand among them, as he grudgingly admits.

Does Sand really believe what he writes? He himself participated in one of the most unusual social events of the second half of the 20th century: the kibbutz galuyot, the meeting in Palestine—later Israel—of millions of Jews from different parts of the world and their amalgamation into a new Jewish society and successful nation state. There were huge cultural differences among these diverse Jewish groups. In looks, language, traditions, occupations, social structures, and relations with their non-Jewish environments, a Jew from Russia and a Jew from, say, Yemen had little in common. Nonetheless, they found the inner resources to establish a state, to live together, to intermarry, and to develop a modern country where most of the inhabitants now seem content—Shlomo Sand among them, as he grudgingly admits.

The State of Israel is one of the most surprising and successful political accomplishments of the modern era. Where does it come from? Sand recognizes that a national reality has been created in Israel. He stresses that this new reality is important, indeed inescapable, for him, and he defines himself as an Israeli. And yet he is blind to the fact that Zionism succeeded in large part because the Jews already were a people belonging—and seen by others to belong—to a distinct nation.

How was it possible for the Jews, in the hour of their greatest collective despair following the destruction of European Jewry, faced with the political and military opposition of the entire Arab Middle East, the animosity of the British, and the relative indifference of the Americans, to manage a political feat that has no parallel in modern history? Sand’s answer, unsupported and unsupportable, is that it was a response to the Holocaust. Whose response? Anyone familiar with the discussions at the UN in 1947 knows what a small role the Holocaust played in the considerations about the future of Palestine. Furthermore, the basic institutions of a Jewish state had already been established long before the UN resolution of November 1947.

In the endless Arab literature on the conflict with the Zionists over Palestine, there is virtually no recognition that Jewish attachment to the land originated in anything other than the persecutions suffered by Jews in Europe. This is an astonishing blind spot and undoubtedly a major obstacle, perhaps the major obstacle, to peace. To dismiss Jewish peoplehood and ahavat zion as modern inventions at best loosely inspired by obscure religious beliefs, as Sand repeatedly does, is bad history and bad politics.

How I Stopped Being a Jew is a quasi-memoir, but Sand doesn’t tell us whether there was ever a time when his own Jewishness had any positive content. As a budding Marxist, his father had rebelled against his religious upbringing in his youth, but Sand doesn’t describe his own childhood. He does mention that it wasn’t until he was an adult that he read from the haggadah on Passover.

At some point, Sand adopted the Russian Jewish writer Ilya Ehrenburg’s post-World War II credo to remain a Jew as long as a single anti-Semite remained on earth. But, Sand proceeds to say, “And yet, as the years have passed, and in view of the radicalization of Israeli politics, especially the shifts that have taken place in its politics of memory, my assurance in this definition of my identity has steadily eroded.” At bottom, Sand’s abandonment of the defiant but apparently rather shapeless Jewish identity to which he had previously adhered stems from his dismay at what he perceives to be the way in which others have put Jewishness to use.

The real meaning of being a Jew in the State of Israel today, Sand says in a statement of breathtaking disingenuousness, is to be, “first and foremost, a privileged citizen who enjoys prerogatives refused to those who are not Jews, and particularly those who are Arabs.” And what does it mean to be a secular Jew outside of the State of Israel? Basically nothing: “We must recognize that the key axis of a secular Jewish identity lies nowadays in perpetuating the individual’s relationship to the State of Israel and in securing the individual’s total support for it.” Israel, in Sand’s opinion, does not deserve such assistance. Nor should it be able to manipulate the memory of the Holocaust:

Despite Israel being the only nuclear power in the Middle East, it regularly reinforces terror in its supporters across the world by pointing on the horizon to the spectre of a repeated Holocaust.

Having witnessed what he views as the pernicious and dangerous uses to which Jewishness is now being put, Sand wishes to shed his “tribal Judeocentrism,” just as his father once fled from Judaism.

It is Sand’s personal right to regard himself as an Israeli rather than a Jew, but the vast majority of his fellow Israelis are bound to and proud of their Jewish heritage and are just as keen as Sand for a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Imagining, as he does, that identities are easily invented, Sand posits an imagined non-Jewish Israeli identity, a kind of Israelism, shared by both Israeli Jews and Arabs. It would be pretty to think so, but most of Sand’s neighbors know otherwise.

It is perhaps here that one should note that the actual Middle East inhabited by a theocratic Iran with nuclear ambitions and Arab regimes whose wishes and intentions regarding Israel are far from neutral is nowhere in evidence in Sand’s writings. Indeed, according to mainstream Arab opinion, Sand should return to Europe, where he was born.

According to Sand, by the end of 2012, his work had been translated into 21 languages. Why are Shlomo Sand’s books so popular?

In 2013, Monika Schwarz-Friesel, a professor at the Technische Universität in Berlin, and I published an analysis of thousands of emails sent to the Israel embassy in Berlin and to other Jewish institutions and persons in Germany, along with emails sent to Israeli embassies in several other European countries. What became clear from both the language and content of these letters from ordinary Europeans was that Jew-hatred, with its traditional tropes and obsessions, has not disappeared. Nor, contrary to common assumptions, is it restricted to right-wing extremists. It is firmly anchored in the affluent, educated middle class of Western society, and its major target is the State of Israel as a Jewish state. Arab propaganda, well organized and lavishly financed, undoubtedly plays an important role in disseminating the seeds of Judeophobia, but they fall on historically fertile soil.

Shlomo Sand, who blithely writes of “the philo-Semitic, ‘Judeo-Christian’ Europe of today” is blind to this phenomenon. In fact, he is worse than blind. In several places in How I Stopped Being a Jew, he flirts, consciously or unconsciously, with anti-Semitic tropes himself. To give just one example, toward the end of the book he writes “the State of Israel belongs more to non-Israelis than it does to its citizens who live there. It claims to be an inheritance more of the world’s ‘new Jews’.” If you don’t know who these “new Jews” who own Israel are, Sand immediately provides a helpful list in parentheses:

For instance, Paul Wolfowitz, former president of the World Bank; Michael Levy, the well-known British philanthropist and peer in the House of Lords; Dominique Strauss-Kahn, former managing director of the International Money Fund; Vladimir Gusinsky, the Russian media oligarch who lives in Spain.

Sand and his Jewish colleagues, in and outside of Israel, ought to pause and reflect about the direction in which their endeavors are headed. It would be a tragic irony if they helped prepare the intellectual ground for a new and much fiercer wave of anti-Jewish agitation.

Suggested Reading

Oh Homeland, Don’t You Wonder (Tzion Ha-lo Tishali)

Dan Alter translates Judah Halevi's poem of yearning for Zion from nearly a thousand years ago.

Fruit of the Fall

The forbidden fruit has been said to be anything from a fig to a banana, so how did the world settle on an apple?

Unsettling Days

Assaf Gavron’s The Hilltop is a refreshing reminder that traditional realism is still an effective vehicle of insight into contemporary society and politics.

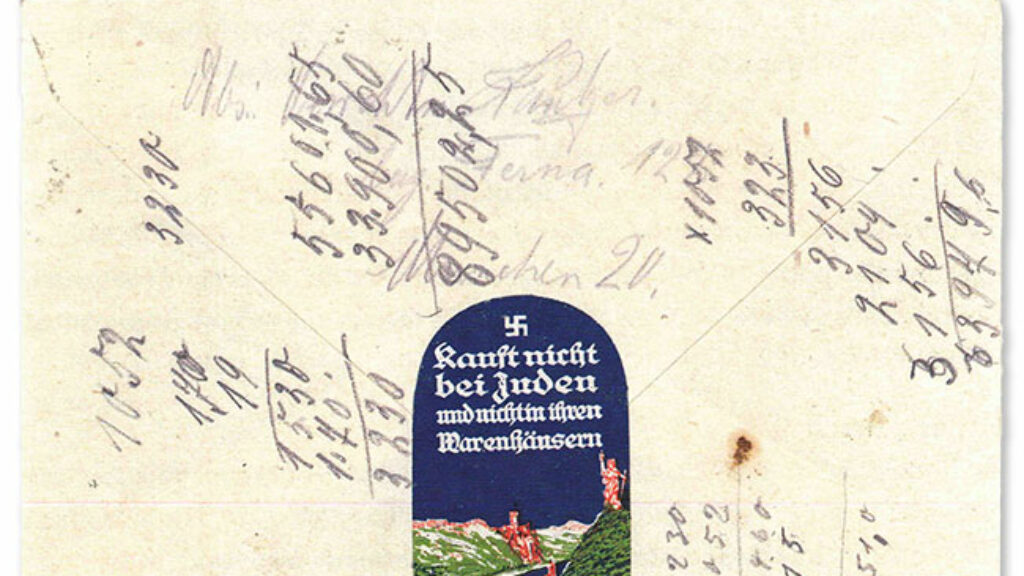

Postcards from the Shoah

Stamps and the paper they traveled on create a historical record of the Holocaust, capturing, for instance, “the exact historical moment when one person reached out in desperation to another."

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In