Jewish Geography

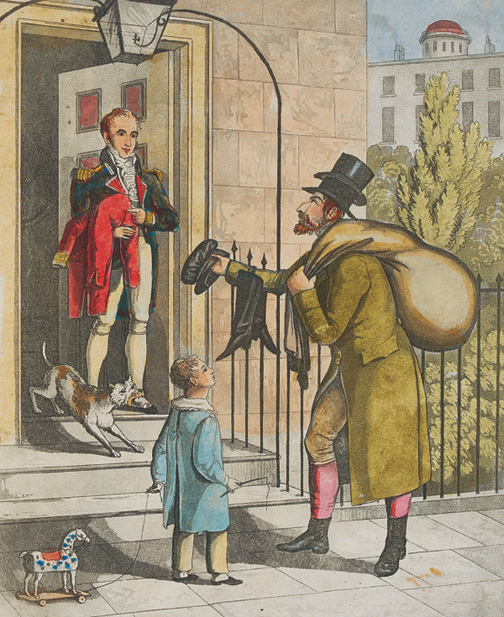

Walt Whitman may have sung the praises of the open road, but for his contemporary, the Jewish peddler shouldering a 160-pound pack as he made his way over dusty trails in the Australian Outback or down country lanes in Wales, that life left a lot to be desired. Peddling, as Hasia Diner’s latest book, Roads Taken: The Great Jewish Migrations to the New World and the Peddlers Who Forged the Way, makes clear, was not an occupation for a nice Jewish boy. Wherever he and his coreligionists went—just about everywhere, it turns out—the “Jew peddler” faced challenges that were at once cultural, economic, and meteorological. Staring down the hostile expressions of those who bristled at his rootlessness, let alone his Jewishness; competing with local storeowners who took offense at his lack of fixed expenses; traipsing through snowdrifts in winter and hiding from the blazing sun in the summer—the Jewish peddler, the “slave of the basket or the pack; then the lackey of the horse,” did not have an easy time of it.

You get the sense that Diner, whose substantial and wide-ranging body of work encompasses a study of American foodways, as well as an inquiry into the public culture of Holocaust remembrance, is rooting for these itinerant purveyors of goods and ideas, determined to rescue them from the shadows to which both economics and history have consigned them. Deeply and richly researched, festooned with colorful detail, her account follows their peregrinations as they cut a wide geographical swath through the United States and South Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America of the 19th and 20th centuries.

What renders the narrative particularly fresh and compelling is its sensitivity to the fundamental tension that lies at the heart of peddling: A bundle of contradictions, these men (and they were almost all men) were strangers who trafficked in intimacy. Crossing a threshold which, under ordinary circumstances, would be closed to them, they insinuated themselves into the lives of their customers. Peddlers stoked and satisfied a desire for possessions: mirrors, eyeglasses, buttons, picture frames, bedspreads, suspenders, and statues of the Virgin Mary. Diner quotes the early 19th-century English poet Robert Southey who disdainfully cataloged the contents of the peddler’s pack while also hinting slyly at the occasional incongruity between the man and his wares:

There are Jew peddlers everywhere traveling with boxes of haberdashery on their backs, cuckoo clocks, sealing wax, quills, weather glasses, green spectacles, clumsy figures in plaster of paris, which you see over the chimney of an alehouse parlor in the country, or miserable prints of the King and Queen, the Four Seasons, the Cardinal Virtues, the last Naval Victory, the Prodigal Son, and such like subjects; even the Nativity and the Crucifixion.

Saddled with stuff, the Jewish hawker, or smous as he was called in South Africa, did more than just peddle. Though the working life of a peddler typically lasted no more than a decade—hardly anyone considered it a proper career—its implications for modern Jewish life, Diner argues persuasively, were as numerous as the items in his pekl, and as consequential, too. A catalyst of migration, an agent of modernization, the harbinger of news, founding father of hundreds of Jewish settlements throughout the world, a de-fanger of stereotypes who not only “exposed people to Jews as real people,” but also dealt with newly emancipated slaves when no one else would, the Jewish peddler was as influential as he was ubiquitous. “The world the peddlers and their customers forged together constituted a new chapter in Jewish history, one that made the new world different than the old,” Diner writes.

For all his many virtues, the “Jewman” was not always welcomed with open arms. Customers (and latter-day historians) might delight in his presence, but legislators, storekeepers, and clerics did not. The many disturbing examples of anti-peddler animus that Diner uncovered will be new to most of her readers. We learn of successful efforts to restrict peddling licenses to the native-born, of the posting of signs whose bold letters screamed “No Peddlers Allowed,” and of public demonstrations and dramatic boycotts like the one that roiled Limerick in early 20th-century Ireland.

That the established Jewish community was not always well-disposed toward its peddling brethren either is another one of Diner’s many revelations. Peddling was thoroughly enmeshed in the broader Jewish ethnic economy where, Hatzfirah, a Russian-Jewish periodical, noted evocatively in 1891, wholesalers of dry goods would propel peddlers off into the wild “like Noah sending the dove from the Ark.” What’s more, many of the modern Jewish community’s leading lights had once been peddlers themselves. All the same, thinking ill of coreligionists on the move was not uncommon, while attempts to “exterminate peddling,” as the Jewish Alliance of America infelicitously declared in 1890, by encouraging farming and other more sedentary pursuits, were thick on the ground.

By highlighting the centrality of peddling to the modern Jewish experience, Diner’s account prompts us to take the measure of its global reach. An exercise in transnational history, her book also reflects the recent economic turn in Jewish studies, whose sophisticated understanding of the marketplace has, of late, invigorated the field. Still, I could not help wonder whether our understanding of the far-flung phenomenon of peddling might have been enhanced had the people who move in and out of the volume’s pages been more fully fleshed out and realized. All too often, they don’t inhabit the narrative as much as illustrate a point. Writing, for instance, about Julius Meyer, whose dealings with the Pawnee earned him the sobriquet of “Box-Ka-Re-Sha-Hash-Ta-Ka,” Diner simply tells us that he “helped stimulate a market for Indian arts and crafts around the world.” Surely more could be made of the “curly-headed white chief who speaks with one tongue.”

The same goes for the material culture that is at the heart of the story Diner tells. Thanks to her eye for detail, we come away with a clear sense of the peddler’s inventory. Less fully developed or sustained is its larger meaning. How Jewish peddlers obtained their wares and distributed them is fascinating, to be sure; of equal moment, I should think, is what the growing availability of eyeglasses and mirrors, photographs, and trinkets betokened. This is, after all, a study in the circulation of goods. Now and again, it seemed if Diner was just about to go down that road, writing effectively, for example, of the ways in which the sale of spectacles promoted literacy. But what about the rest of it? How did owning and gazing into a mirror promote a sense of the self? And what of color and texture that enlivened one’s surroundings? Or the pursuit of fashion and novelty that quickened the appetite?

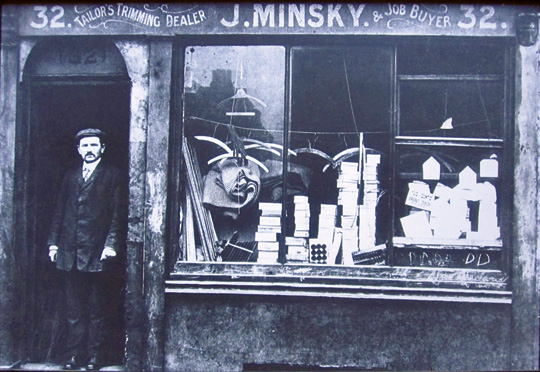

The Rag Race: How Jews Sewed Their Way to Success in America and the British Empire, Adam Mendelsohn’s first book, reckons directly with the discarded rags, second-hand clothes and spit-and-polish uniforms that fill its pages. An inquiry into the wellspring of modern Jewish economic success, it attends to the origins of the garment industry, poking around in the dusty, and often little-known, corners of a global exchange based on kinship and the Jewish collective. Focusing on the “old clo” man and other unsung heroes of Jewish history, Mendelsohn’s objective is to revamp, or, as the lingo of the market in second-hand goods would have it, “renovate,” our understanding of the past. “This attention to ‘old clo’ dealers is one of the ways this volume cuts, crimps and reworks several pieces of the standard narrative of the economic history of the Jews in England and the United States,” he writes, drawing heavily and characteristically on verbs that trumpet his subject’s roots in the making of things to wear.

Shuttling between Petticoat Lane in London and Chatham Street in New York, between that self-styled “Eldorado on the shores of the Pacific,” a rosy-eyed reference to California, and an auction mart in Melbourne, which, wrote one disgruntled eyewitness, “might have been mistaken for a Jewish synagogue,” Mendelsohn vividly documents the process by which clothing made the rounds. Well before globalization became the darling of the contemporary academic curriculum, the Jews made it a common practice.

As wide-ranging in scope as the ambitions of Elias Moses and Joseph Seligman, whose transmogrification from itinerant peddlers into respectable bankers underscores the book’s main theme—the “alchemy” of success—this study situates the nascent apparel trade within such varied contexts as the California gold rush, the development of the British Empire, and Civil War procurement practices. Were it not for the presence of Jewish peddlers or “Jehudem,” who, like Levi Strauss, plied their trade in the mining camps outside of San Francisco; the Jewish clothiers who sold “emigrant outfits” to those who sought their fortunes in Australia; or the participation of Jewish wholesalers from Cincinnati in outfitting Union troops with hats and boots, jackets and pants, the modern garment industry as we know it would not have come into being. “…To begin a discussion of Jews and the clothing trade in America with the sweatshop is like presenting a stage play without its opening acts,” Mendelsohn chides, adding “the role of earlier immigrants in opening the arena and designing the props essential for the success of the later drama has not been fully recognized.”

To make his case, he marshals a stunning array of sources, whose ranks include the writings of Dickens and a dictionary of British slang, petitions to the lord mayor of London, 19th-century travel literature and advertisements galore, among them this amusing piece of doggerel, courtesy of the house of E. Moses & Son:

A dress coat, if it fit too tight/Will make the wearer look a fright./

And if the garment fit too loose, /It scarcely is of any use.

Exhaustively and imaginatively researched, Mendelsohn’s book is replete with detail—so much so that at times the reader gets lost. The text sprawls in narrative ways as well and would have benefited greatly from a much tighter structure. That it, too, like Diner’s account, ultimately treats clothing more as an economic object of exchange than as an independent cultural phenomenon was a further source of disappointment.

And yet, for all the snags in its fabric, The Rag Race is a remarkable achievement, a testament to the vitality of the historical imagination. So, too, is Roads Taken, an exhilarating display of research and synthesis. While each volume stands tall on its own, they are even more profitably read together. They remind us that the volatile and complex world of fashion can find a home in the academy as well as on the street.

Suggested Reading

No Sex in the City: On Srugim

A new Israeli TV show chronicles single life in Jerusalem.

A Lone Soldier

Every year, when Yom HaZikaron, Israel’s memorial day, rolls around, the author thinks of an idealistic college student named Alex Singer who became a lone soldier in the IDF.

Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh Walk into a Bar: Passover in the Union Army

Yankee ingenuity at Passover: how one regiment made a Seder in the midst of the Civil War.

Getting Along with the Gentiles

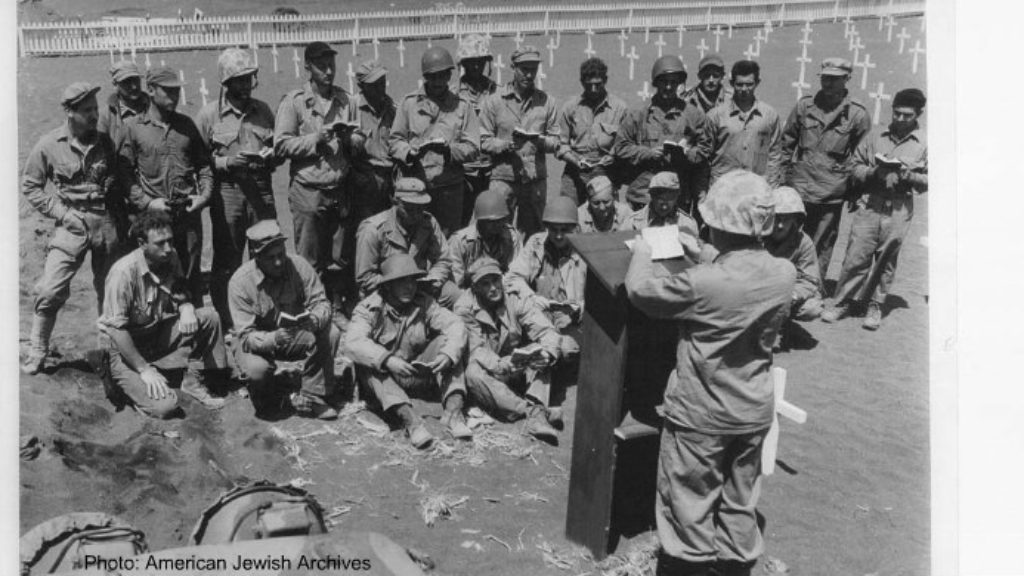

From the Brandeis Book Stall to the sands of Iwo Jima (and halakhic flexibility).

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In