An Affair as We Don’t Know It

Captain Alfred Dreyfus can’t be the “spy” in the title of Robert Harris’ recent historical thriller, since he was entirely innocent. An Officer and a Spy, newly out in paperback, is, in fact, mostly about Lieutenant-Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart, the French Army counter-intelligence chief who eventually proved that the Jewish captain had been falsely accused and wrongly convicted of spying for Germany.

Harris retells the “Dreyfus Affair” from Picquart’s point of view, dramatically reconstructing how he zeroed in on the true culprit, Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, by setting up, among other things, a wonderfully quaint fin de siècle stake-out in the neighborhood of the German embassy in Paris. The climactic moment, however, comes at Picquart’s desk, staring at a recently obtained specimen of Esterhazy’s handwriting:

The writing is neat, regular, well spaced. I am almost sure that I have seen it before. At first I think it must be because the script is quite similar to that of Dreyfus, whose correspondence I have spent so many hours studying lately.

That was something Picquart had been ordered to do, in the hope that he would find additional evidence concerning Dreyfus’ motives.

And then I remember the bordereau—the covering note that was retrieved from Schwartzkoppen’s waste-paper basket and that convicted Dreyfus of treason.

I look at the letters again.

No, surely not . . .

The bordereau, in facsimile, is a column of thirty narrow lines of handwriting—undated, unaddressed, unsigned . . .

The leading handwriting expert in Paris swore that this was written by Dreyfus. I carry the photograph over to my desk and place it between the two letters from Esterhazy. I stoop for a closer look.

The writing is identical.

Harris, a well-known British novelist with eight best-sellers to his credit, dramatically depicts Picquart’s transformation into what we now call a whistle-blower who switched sides and became the star witness for the “Dreyfusards,” the defenders of the Jewish captain imprisoned on Devil’s Island.

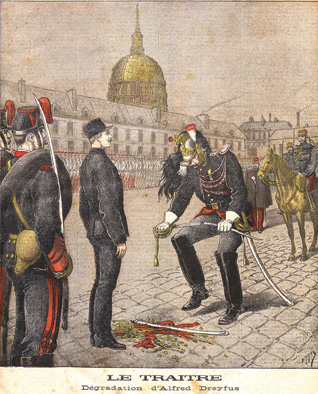

Picquart was a conservative Catholic and, as Harris makes clear, he did not like Jews—but then, few did. Nonetheless, he was fair-minded, and he understood that “The Affair” was not only a public moral failure but a political calamity for the French Army. The truly staggering moment, as Harris is well aware, was not so much Dreyfus’ ghastly public degradation in January of 1895, but his retrial and re-conviction four years later.

Late in the novel Picquart says to a group of Dreyfusards, including the prominent novelist Émile Zola and the journalist and future prime minister Georges Clemenceau:

What I do believe is that somehow this affair must be taken out of the jurisdiction of the military and elevated to a higher plane—the details need to be assembled into a coherent narrative, so that everything can be seen for the first time in its proper proportions . . . Reality must be transformed into a work of art, if you will.

Harris then has the sly and knowing Émile Zola reply, “It is already a work of art, Colonel . . . All that is required is an angle of attack.” Something similar might be said to Harris.

When Harris’ skillful and absorbing historical thriller appeared last year, it is not likely that many people read it with current events in mind. (Or if they did it was in a more general sense, in line with the blurb on the recent paperback edition: “A whistle blower. A witch hunt. A cover-up. Secret tribunals, out-of-control intelligence agencies, and government corruption. Welcome to 1890s Paris.”) Now, however, in the aftermath of the massacres that took place in Paris in January and with so much news about Jewish emigration from France, readers may come to Harris’ novel not only to hear an exciting tale but with some hope that it will help them better to understand the present-day France. If so, that would be unfortunate.

According to the standard version of the Affair, which Robert Harris’ tale faithfully reflects, Dreyfus was condemned because he was Jewish and because France was an anti-Semitic society, notwithstanding the fact that the country had emancipated its Jews a century earlier. The ugly truth about France finally emerged at the end of the century when the French military elite, made up of Catholics in its great majority, conspired to accuse and arrest the only Jew on the General Staff. It took three years before the real story began to spill out. And even as it did, as Harris recounts, the going view was that of the French minister of war: “We simply can’t allow ourselves to be distracted from these great issues by one Jew on a rock. It would tear the army to pieces.” Largely thanks to Picquart, however, the forces of light managed to pull themselves together and take up the cudgels on the innocent Jew’s behalf. It then took another eight years—so, 11 in all—of enormous social and political turbulence that rent French society before the unhappy captain received a full pardon and reinstatement at the rank of major.

What’s wrong with this version of events? It has long been fashionable to quote the lament of the great writer Charles Péguy that “everything [in the Affair] began as mystique and ended as politique.” This sounds glorious but is misleading, for the truth is that the Dreyfus Affair, from start to last, for better or worse, was about politics—and that includes the Affair’s career in posterity. Notwithstanding the mountain of unproven assertions and unwarranted assumptions to the contrary, the obsession with Dreyfus did not contort and convulse the whole of France. If we keep this gentle reminder firmly in mind, we shall have a much easier time understanding both what the Affair was about—and what it was not: namely, a crusade of evil against good. Much serious scholarship is there to tell us—and Robert Harris, if he had engaged in a more thorough study of the latest research—that the French had, as they like to say, other cats to whip. The “Dreyfus obsession,” as a leading historian of this period, Bertrand Joly, terms it, was largely a retrospective construction.

The social-psychological background against which everything took place in France in this period was the national resentment and self-defensiveness that accumulated in the wake of the country’s shocking military loss to Prussia, coupled with the latter’s transformation into the Kaiserreich—and at Versailles, no less. What Harris aptly calls “the lingering stench of defeatism after 1870” saw France develop a semi-conscious xenophobia and quasi-revanchist focus on military, diplomatic, and “national” might, together with a cult of its army (“the sacred Ark”) that hadn’t been seen since the Napoleonic empire. And as for spies, France caught a long-term case of what the historian Vincent Duclert calls, “veritable espionnitis.”

Second, now that the Republic was re-established (after its overthrow in 1852, by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte), the century-old rivalry between church and state returned with a vengeance. The Rome-Republic tension defined the era—and the Dreyfus Affair. What is essential to keep in mind is that French Catholics, though not quite persecuted, had good reason to feel penalized for publicly practicing their religion. Both church and state developed a real paranoia about the other, tending to see the hand of its enemy at every turn, while resorting to the highest-flown moral-ideal language to combat it. Given this explosive tension, it is quite remarkable how comparatively uninvolved the Catholic hierarchy itself remained in the Dreyfus case. Leo XIII made it clear that he thought the captain innocent. This said, priests and religion’s secular hacks were another matter, and this is where anti-Semitism came in.

Third, and finally, the Third Republic itself had serious structural weaknesses that made it hard for it to create enduring parliamentary majorities. French governments in these years were hopeless at dealing decisively with any crisis. Many politicians, including several prime ministers, privately had severe doubts about Dreyfus’ guilt and qualms about the military’s railroading of him but they were not inclined to take on the Ministry of War.

Dreyfus was arrested because there was some evidence to incriminate him and because his superiors were desperate to find a culprit. The fact that this captain was rich, arrogant, secularly trained (at L’École polytechnique, the French version of MIT, rather than West Point), and Jewish only further justified his arrest. The going logic was, in Joly’s priceless words, “It’s perhaps he, so then it must be he.” The military justice machine went into high gear to justify the hasty arrest. Rather than back off, the brass compounded error upon error, lie upon subterfuge, each step making it harder—and soon, impossible—for them to stop or step backward without ruining their own and the Army’s reputation. Until Picquart changed his mind, after Dreyfus’ first conviction but before the second, no one even tried to stop this implacable flight forward.

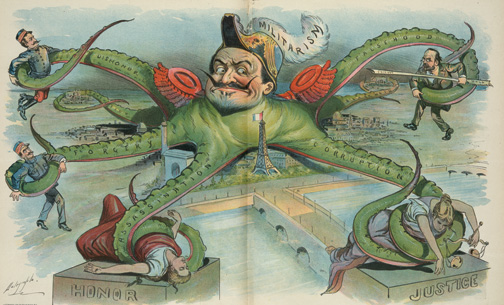

The Affair became politicized, then highly politicized, as it became clear that all sides on the contentious French public scene could use it to do their old business destroying each other’s reputations. The great success of the handful of leading anti-Dreyfusards lay not in rallying “the French against the Jew” but in managing to project and sustain the myth that the cause of a few criminal officers in military justice was the cause of the Army, hence (automatically) the cause of the “wounded” country.

But what about the infamous anti-Jewish riots that took place in the winter and spring of 1898, following Zola’s exposé of the framing of Dreyfus in his “J’Accuse”? Harris is indeed true to the facts when he has Picquart observing an anti-Semitic demonstration in the Boulevard du Palais in Paris where there are cries of “Death to the Jews!” “Death to the traitors!” “Yids to the water!” Nor is he fictionalizing when he reports what Picquart witnesses a little later:

We cross the river and have barely travelled a hundred metres along the boulevard de Sébastapol when we hear the cascading sound of plate glass shattering and a mob comes running down the centre of the street. A man yells, “Down with the Jews!” Moments later we pass a shop with its windows smashed and paint daubed across a storefront sign that reads Levy & Dreyfus.

And not only in Paris but in a score of other French cities, jeering throngs spewed epithets at many targets, including the Jews. But, as Joly and others have shown, the crowds usually numbered only in the hundreds, rarely the thousands. They did material damage but shed no blood, and the turbulence stopped as swiftly as it arose, requiring only modest repressive action from police or military.

Even at the height of the Affair, Judeophobia did not translate into electoral support for enemies of the Jews. The elections of 1898 saw 23 deputies (out of a total of 565) returned to the Chamber whose political platforms contained anti-Semitic discourse, in some guise or other. These men were to prove wholly inactive, and all were defeated in the next elections. By contrast, the numerous Austro-German anti-Semitic political parties mobilized hundreds of thousands of voters over two decades, and in the case of Vienna, the municipal administration of the capital fell into the anti-

Semitic groups’ hands for a generation.

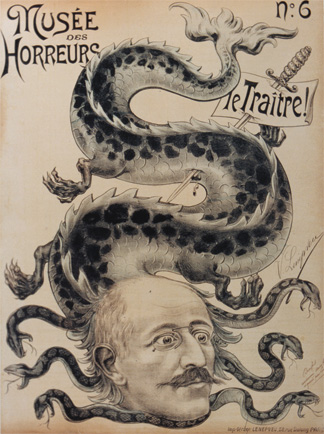

Édouard Drumont, the only important French anti-Semite, was certainly a rhetorical force to be reckoned with at home throughout the years of the Affair, with his incendiary denunciations of the “big Jews and their accomplices” who ought to be court-martialed and executed. But Drumont was a political pariah who was viewed as a corrupt monomaniac. The few dozens of secondary and tertiary French anti-Semites who trailed after him were largely immature adolescents, a handful of failed artists, some police spies, and a plethora of accomplished hucksters and embezzlers. What is remarkable is how this farrago of frauds has mesmerized so many historians who have taken them for what they said they were.

The French public of the Dreyfus years did not dream of a Holocaust avant la lettre; they simply could not quickly make sense of the shrill opponents attacking each other and haranguing “the people” on all sides. Partly this ignoring of what posterity so badly wants to see as the leitmotif of the Affair stems from the fact that the France of the 1890s had very few Jews: around 80,000 in a population of 35 million. Many Frenchmen had never met one. The would-be assassin of Dreyfus’ lawyer at the retrial at Rennes in 1899 ran off after he shot Labori yelling, “I’ve just killed a Dreyfus,” meaning, one suspects, “a Jew.” (Labori was a practicing Catholic.) It took a solid year or two before all the disclosures of what really happened turned the tide of opinion against the anti-Dreyfusards. Finally, it became politically correct to see not simply the innocence of Dreyfus (which was, after all, long suspected) but the stupidity and criminality of a few officers, who did not necessarily represent “the Sacred Ark” of France’s army. This empowered a craven and weak government to act, and presently the Affair ended. But the fulcrum on which it has turned is not, was never, “the Jew”; it was raison d’État versus the rights of man.

At many points throughout the Affair, many parties tried to “explain” what was “really happening” in terms of plots against the state or the society—Jesuit, Freemason, Jewish, anti-militarist-anarchist, anti-clerical, anti-Semitic, and so on. Such thinking, such mendacity, such nonsense gained a lot of temporary ground, but few people took these allegations seriously for long. They were elements of verbal escalation in bitter partisan wars.

What we need to keep in mind—as Robert Harris certainly does not—is that the anti-Dreyfusard wave which unquestionably swept France did not imply widespread approval of Drumont or his anti-Semitic cause. Even most anti-Dreyfusard newspapers ignored the anti-Semites when they did not revile them, and the same held for most of the leading nationalists. Camille Krantz, who became minister of war in 1899 and was personally convinced of Dreyfus’ guilt, detested the Jew-haters (“they inspire me with absolute repugnance”) and refused to shake Drumont’s hand. Nor, on the other hand, were the leading Dreyfusards particularly wrought up over the Jewish question. When the League of the Rights of Man was founded in 1898 its statement said nothing about combatting anti-Semitism but spared no shot in firing at counter-revolution and clericalism, while equating Dreyfusardism with the battle for liberty, fraternity, and equality.

Seeing the Dreyfus Affair through the same lens as we view, say, the Mendel Beilis trial and the Leo Frank lynching of roughly the same period is common but mistaken. The blood libel accusations against Beilis in Kiev and of rape and murder against Frank in Georgia centrally turned on the accused’s religious identity, while in the Dreyfus Affair, this was (mainly) not the case. This is not to say that the assertion (far more than sincere belief) that the Affair turned on “the Jewish Question” was absent at the time—far from it!—but it was the product of small highly partisan groups, making political capital. Outside of France, however, it became the common wisdom.

Pastors in upstate New York preached to their flocks that “all the world is watching the second trial of Captain Dreyfus because Dreyfus is a Jew,” while an American publication (The Independent) waxed more erudite, “Nothing but the story of Esther and the Book of Job can equal the Dreyfus case in the symmetry of its ending.” Newspapers in Wilhelmian Germany and tsarist Russia—two infinitely more anti-Semitic societies than democratic France—welcomed the opportunity to chastise the preachy and superior French Republic. But in France itself matters were less clear. In 1994, the centennial of the arrest and trial of Dreyfus, a French scholarly review published an issue devoted to nine country-by-country studies of cartoons that appeared in Britain, France, and Germany at the time of the Affair. It is curious to note that not one of the 57 images from French publications contains an anti-Semitic or Judeophobic theme.

It was understandably the Second World War that launched a reconsideration of the Dreyfus Affair. “[The Dreyfus Affair was] a huge dress rehearsal for a performance that had to be put off for more than three decades,” wrote Hannah Arendt. There was, it is true, plenty of Judeophobia on the French landscape of the late 1890s—as there was in every European country. But what the French had more of than other countries was freedom of expression, together with an old tradition of violent, virulent polemics. The tiny handful of professional anti-Semites did themselves proud in this department, but this was the distant threnody in a minor chord of the long history of contempt for Jews and the use of “Jew”-language for every negative purpose.

So is history of any help to us in parsing the undeniable spike in Jew-hatred in France and elsewhere in Europe these days? Possibly, but not until we clean the Augean Stables before filling them up again. Despite her irresistible brilliance and good heart, Hannah Arendt had it wrong. L’Affaire (as the French still call it) is a complex saga which, at its most depressing, presents a truly pitiable portrait of French society and the Republic, but it wasn’t a “dress rehearsal” for anything. By 1899, both society and the Republic began to pick themselves up and do the right thing and continued to do so until the Nazis brought France’s anti-Semites to power during their occupation of the country.

As for the genuinely alarming events of today, it is important to register that the attackers are not assailing Jews in the name of France. In fact, it is hard to imagine a premier of an earlier Republic stating, as Monsieur Valls recently did, that if 100,000 Jews left France to make aliyah, “France will no longer be France.”

This being said, there is a connection between the anti-Semitism of the “old” France, and other Christianity-inscribed societies, and the violence of today. Muslim anti-Semitism no longer consists mainly in the contempt that the historian Bernard Lewis correctly distinguished from hatred. Rather, as Britain’s former chief rabbi, Jonathan Sacks, has pointed out, it traffics in the kind of chimerical charges and explosive violence, backed by official complicity or indifference, that once characterized anti-Semitism in nominally Christian cultures, from Imperial Russia and Austria to Nazi Germany—and yes, though to a far lesser degree, the French Third Republic.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

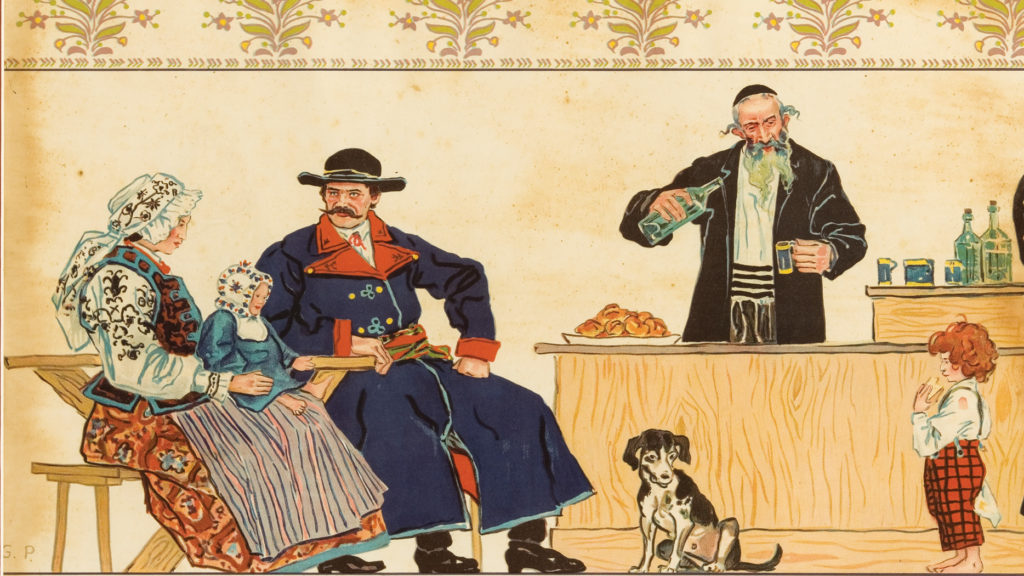

Poland’s Jewish Problem: Vodka?

Jewish-run taverns—rowdy, often very seedy drink-holes—served to cement, rather than sour, the impossibly tense and intertwined lives of Poles and Jews, as a new book by Glenn Dynner shows.

The Fifth Question

Whatever kind of Passover Seder one attends, there is a fifth question, usually whispered, that arises some time after the first four are asked . . .

The Anti-Jewish Problem

In the competition that took place between Judaism and nascent Christianity, only one could be correct. Thus, anti-Judaism became central to the Western tradition.

Water Shall Flow from Jerusalem

In Israel even well-to-do families can be seen scooping bath water out of the tub to water backyard plants and hygiene classes teach students to use the least amount of water when showering and brushing their teeth. Israel's way with water may be the way out chronic water shortages.

Jacob Arnon

I carefully read and reread Steven Englund’s essay on the Dreyfus affair and while there is much there to admire, his review of the new novel about Dreyfus, I felt a sense of letdown by his revisionist thesis.

Professor Englund says: “Édouard Drumont, the only important French anti-Semite, was certainly a rhetorical force to be reckoned with at home throughout the years of the Affair, with his incendiary denunciations of the “big Jews and their accomplices” who ought to be court-martialed and executed.”

Has Englund not heard of Maurice Barres who according to Frederick Brown’s in his important book “The Embrace of Unreason” said "That Dreyfus is guilty, I deduce not from the facts themselves, but from his race?”

The Professor is being led by his revisionist thesis and not by the historical facts when he argues:

“But Drumont was a political pariah who was viewed as a corrupt monomaniac. The few dozens of secondary and tertiary French anti-Semites who trailed after him were largely immature adolescents, a handful of failed artists, some police spies, and a plethora of accomplished hucksters and embezzlers. What is remarkable is how this farrago of frauds has mesmerized so many historians who have taken them for what they said they were.”

Were Renoir and Degas minor painters? These two anti Dreyfussards took out their Jew hatred on their impressionist colleague Camille Pissarro. From all accounts they made his life miserable with disgusting Jew bating.

One of the few French painters to side with Dreyfus was Claude Manet.

These are not quibbles. Professor Englund subjective thesis cannot be proven by the historical evidence. It is not Hannah Arendt who was wrong when she argued that the Dreyfus affair was the time when social antisemitism in France entered the political sphere.

It was not Theodore Herzl who was wrong when he saw in this Affair the beginning of the end of Jewish life in Europe.

Englund reduces the Affair to a “…few dozens of secondary and tertiary French anti-Semites who trailed after him (Drumont) were largely immature adolescents, a handful of failed artists, some police spies, and a plethora of accomplished hucksters and embezzlers.”

Englund offers no objective proof to support his thesis.

If we are going to look to subjective responses to this Affair reading Proust and other novelists of the period would make more sense.

Finally Hannah Arendt is correct to say that the importance of the Dreyfus Affair lies in the fact two very bloody World Wars could not eclipse its importance.

We cannot ghettoize this historical period as it had an enormous influence on subsequent political development in France and elsewhere.

I would suggest people read Frederick Brown biography of Zola as well as his more recent book some of the figures who created a modern antisemitic language which was picked up by later antisemitic fascists and National socialists:

“The Embrace of Unreason: France, 1914-1940” by Frederick Brown who explores the tumultuous forces unleashed in the country by the Dreyfus Affair.

Jacob Arnon

I carefully read and reread Steven Englund’s essay on the Dreyfus affair and while there is much there to admire, his review of the new novel about Dreyfus, I felt a sense of letdown by his revisionist thesis.

Professor Englund says: “Édouard Drumont, the only important French anti-Semite, was certainly a rhetorical force to be reckoned with at home throughout the years of the Affair, with his incendiary denunciations of the “big Jews and their accomplices” who ought to be court-martialed and executed.”

Has Englund not heard of Maurice Barres who according to Frederick Brown’s in his important book “The Embrace of Unreason” said "That Dreyfus is guilty, I deduce not from the facts themselves, but from his race?”

The Professor is being led by his revisionist thesis and not by the historical facts when he argues:

“But Drumont was a political pariah who was viewed as a corrupt monomaniac. The few dozens of secondary and tertiary French anti-Semites who trailed after him were largely immature adolescents, a handful of failed artists, some police spies, and a plethora of accomplished hucksters and embezzlers. What is remarkable is how this farrago of frauds has mesmerized so many historians who have taken them for what they said they were.”

Were Renoir and Degas minor painters? These two anti Dreyfussards took out their Jew hatred on their impressionist colleague Camille Pissarro. From all accounts they made his life miserable with disgusting Jew bating.

One of the few French painters to side with Dreyfus was Claude Manet.

These are not quibbles. Professor Englund subjective thesis cannot be proven by the historical evidence. It is not Hannah Arendt who was wrong when she argued that the Dreyfus affair was the time when social antisemitism in France entered the political sphere.

It was not Theodore Herzl who was wrong when he saw in this Affair the beginning of the end of Jewish life in Europe.

Englund reduces the Affair to a “…few dozens of secondary and tertiary French anti-Semites who trailed after him (Drumont) were largely immature adolescents, a handful of failed artists, some police spies, and a plethora of accomplished hucksters and embezzlers.”

Englund offers no objective proof to support his thesis.

If we are going to look to subjective responses to this Affair reading Proust and other novelists of the period would make more sense.

Finally Hannah Arendt is correct to say that the importance of the Dreyfus Affair lies in the fact two very bloody World Wars could not eclipse its importance.

We cannot ghettoize this historical period as it had an enormous influence on subsequent political development in France and elsewhere.

mostlymaimonides

There are at least 2 factual errors I noted: There was one anti-semitic campaign that succeeded brilliantly in 1898 and that was Drumont's run for Chamber of Deputies in Algiers. He won and served in the Chamber until 1902. And that same Drumont campaign was used to incite riots in Algiers that were responsible for the death of at least one Jew.

Although Arendt's thesis that L'Affair was a dress rehearsal for a certain kind of fascist discourse, neither her thesis or the facts on which she relies have been fairly represented. Curious readers should ponder Arendt's strange and provocative work, the Origins of Totalitarianism for themselves. It is true that the 3rd Republic has many accomplishments worthy of praise following the Affair, and Hannah Arendt would be the first to say amen to that, Drumont's anti-semitic congresses convened all over Europe and laid the foundation for a pan-European anti-semitic, anti-modernist political movement. Those movements influenced some European colonies, as well. Drumont's anti-Dreyfusard-ism had its greatest success among the cultural elite and were not confined to the french language. Its impact can still be perceived in the late writings of Henry Adams and the early poetry of TS Elliot. From 1903 to 1905, events in Romania and Bessarabia, proved that the mythology of the Anti-Dreyfusard's could be useful for inciting violence against Jews in the East. I do not think there are any simple or sweeping comments one can make about the Affair other than it is a matter of enormous importance to France but also to the entire 20th century and still deserves careful attention.