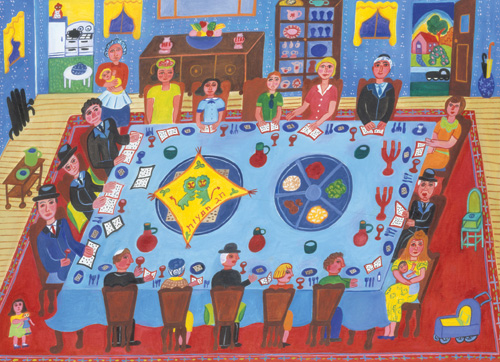

The Fifth Question

Whatever kind of Passover Seder one attends, there is a fifth question, usually only whispered, that arises sometime after those famous four questions which begin the long Maggid (literally, telling) section of the haggadah are recited: “When do we eat?” Of course, the haggadah itself says that “whoever elaborates in the retelling of the story of the exodus is surely praised” and illustrates the point with the famous story of the five sages of the 2nd century, who stayed up all night doing just that:

It happened that Rabbi Eliezer, Rabbi Joshua, Rabbi Elazar ben Azaryah, Rabbi Akiva, and Rabbi Tarfon were reclining at a Seder in Bnai Brak. They were retelling the story of the exodus from Egypt the entire night, until their students came and told them: “Our Masters! The time has come for reciting the morning Shema!”

Writing one thousand years later, Moses Maimonides took this story as precedent in the Mishneh Torah, his code of Jewish law. In his introduction to the laws of the Seder, he writes: “Even great scholars are obligated to retell the story of the exodus from Egypt. And anyone who elaborates in recalling the events that occurred is surely praised.” Three paragraphs later, he spells out what this means:

One begins by recalling that we were slaves in Egypt and recounting all the hardships Pharaoh wrought. But he should conclude with the miracles and wonders that were done for us, and with our freedom. That is, he should expound on the verse “my father was a wandering Aramean” until he concludes that paragraph. And anyone who adds and elaborates is surely praised.

This is the halakhic source for delaying the matza ball soup and brisket. What is surprising, given the text of the haggadah and Maimonides’ position, not to speak of common practice, is that the most authoritative code of Jewish law, the 16th-century Shulchan Arukh, disagrees:

One’s table should be set while it is still daytime, in order to eat immediately as it gets dark. And even if he is engaged in Torah study, he should conclude his studies and hurry [home] as it is a mitzvah to eat right away so that the children not sleep.

Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan (more popularly known as the Hafetz Hayim) was so shocked by this statement that, in his Mishnah Berurah, he insisted on glossing it as urging us to start the Maggid section right away; the talking not the eating. That makes sense in terms of 19th-century Ashkenazi practice, but it is not the plain meaning of the Shulchan Arukh.

In fact, its author, Rabbi Joseph Karo, is drawing upon the great halakhic code that appeared between Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah and his own “Set Table,” the 14th-century Arbah Turim (or Tur) of Rabbi Jacob Ben Asher. Both Rabbi Karo and his predecessor were thinking about the children, but there was also a deeper disagreement with Maimonides at play. Understanding that disagreement will help us understand what the Seder, and to some extent rabbinic thought, is all about.

Neither the Shulchan Arukh nor the Tur even cites the haggadah’s statement that “whoever elaborates in the retelling of the story of the exodus is surely praised.” This is particularly unusual, because the Shulchan Arukh tends to follow Maimonides’ lead—often verbatim—unless a line of competing authorities rule to the contrary. In this case, however, no such authorities are to be found, and yet the prescriptions of both the haggadah and Maimonides are not merely ignored but actually reversed.

The authority for this “hurry-up-and-eat” view appears to come from an early rabbinic text, included in the Tosefta (a collection of texts that parallels and to some extent supplements the Mishnah) and later cited in the Babylonian Talmud:

Rabbi Eliezer states: We grab the matzot so that the children will not fall asleep. Rabbi Yehuda related in his name: Even if he has only eaten one appetizer, and even if he has not dipped in relish, we grab the matzot so that the children will not fall asleep.

What does “grab the matzot” mean? For Maimonides this is the source for common practice of the parents hiding the matza from the children. The Shulchan Arukh and the Tur plausibly take it as a mandate to “grab the matzot” and eat them early in the evening, before the children fall asleep. But this does not mean that the Shulchan Arukh imagines the parents following their children to bed after the meal, at least not ideally:

A person is required to delve into the laws of the Pesach sacrifice and the exodus from Egypt and to recount the miracles God performed for our forefathers until he is overtaken by exhaustion.

The obligation to stay awake all night learning Torah, then, applies after the Seder has been completed. In fact, the section where this ruling is recorded is largely devoted to the rule that one should not drink any more wine after the fourth of the Seder’s legislated cups, in order to stay awake.

Once again, the apparent source for the practice is found in the Tosefta, which presents an alternate, or perhaps parallel, story about mishnaic rabbis who stayed up the night of the Seder:

One does not eat any desserts after the Pesach sacrifice [has been eaten], such as dates. A person is obligated to engage in the laws of the Pesach sacrifice all night. . . . It once happened that Rabban Gamliel and the elders were reclining at a Seder in the home of Beithus ben Zunin in Lod, and they were engaged in the laws of Pesach that entire night, until the rooster crowed. At that time, the tables were removed from before them, and they arose to attend the synagogue.

The first thing to note is that in the Tosefta’s version, the all-night study session took place after the Pesach sacrifice had been eaten (when we would now eat the afikoman), and what we would call the Seder is already over. Second, whereas in the haggadah’s story the rabbis stayed up all night to retell the story and miracles of the exodus, in the Tosefta, they spend all night learning the technical laws of the Pesach sacrifice. Finally, whereas the haggadah suggests that the students had to remind the rabbis to wrap up the Seder because they had lost track of time (the 19th-century Hasidic master the Sefat Emet even suggested that they had forgotten to eat the matza!), in the Tosefta the rabbis were not surprised to find that it was morning. They concluded their discussions and prepared for morning prayers in orderly fashion.

Maimonides never mentions the Tosefta’s story, nor any requirement to stay up all night studying the laws of Pesach. To the contrary, he ends his laws of the Seder with a discussion of what happens when someone falls asleep at the Seder (which will occasionally happen during all that praiseworthy discussion and elaboration). Further, he offers a very different reason for not drinking after the fourth cup: so that the last taste of the matza (the afikoman) remains the final memory of the Seder. For Maimonides, the work of the Seder is done before and during the meal, not after.

I have already noted that, unlike Maimonides, the Shulchan Arukh does not cite the most famous line of the haggadah that “anyone who elaborates in the retelling of the exodus story is praiseworthy,” but, tellingly, it also doesn’t cite what might be its second most famous line, that “everyone must see himself as if he personally participated in the exodus from Egypt.” Why not?

In short, two distinct conceptions of the Seder emerge from the classical rabbinic sources and are codified, respectively, by Maimonides and the Shulchan Arukh. The view of the Mishnah, Maimonides, and the haggadah itself is that what the Seder is about is the retelling and discussion of the story of the exodus from Egypt to the point where one sees oneself as having been personally redeemed. Here, the entire family uses story, study, and song to relive the birth of Jewish nationhood. When successful, this is surely close to the Seder’s ideal. There is, however, also a cost to setting ambitions so high: The kids might fall asleep and the adults may tune out.

The conception of the Seder in the Tosefta and the Shulchan Arukh is more modest. The Seder starts promptly and is (relatively) short so that no one misses out on the essential, legally mandated, ritual elements. Then, once the Seder is over, those with the ability to follow Rabban Gamliel’s lead can stay awake all night discussing the laws of the Pesach. Perhaps it’s no wonder, then, that in the haggadah itself it is Rabban Gamliel who reminds us that “whoever does not mention the Pesach sacrifice, the matza, and the maror has not fulfilled his obligation.” His statement immediately follows the elaborate expositions of the biblical verses, and we can almost hear Rabban Gamliel reminding us to keep the focus on the accessible, tactile experiences of the Seder: the ritual foods and their symbolism. (Incidentally this approach is probably closer to what happened during Temple times, when the food came first and the discussion followed.)

The difference between these two views of the Seder also relates to what is being taught. According to the haggadah and Maimonides, the centerpiece of the Seder is the retelling of the Pesach story, a form of narrative or aggada (a word that shares its root with both haggadah and maggid). By contrast, the Tosefta, whose views are incorporated in the ruling of the Shulchan Arukh, emphasizes studying the laws of the Pesach sacrifice.

A similar distinction runs through another of the Seder’s well-known passages, the discussion of the four sons. In our version of the haggadah, the wise son is taught the laws of the Pesach sacrifice, whereas the simple son is told the basic Pesach story. The Jerusalem Talmud, however, reverses the priorities: The wise son is taught the story of the exodus, whereas the simple son is taught the laws of the Seder.The first view sees in halakha not just a series of rules, but a complex religious world view developed from fundamental legal principles. Law is not only to be observed, but is to be studied, analyzed, and its meaning absorbed. By contrast, the story told to the simple son is just that—a story, for those who can’t handle more. Arguably, the Jerusalem Talmud teaches the exact opposite. In assigning the story of the exodus to the wise son, story comes to mean the theology of Jewish chosenness, the service of God, and the corresponding complexities of freedom, slavery, choice, and destiny. The laws taught to the simple son are, on this account, just ritual directions: eat this, drink that, and so on.

The same tension exists between the two competing stories of how the great rabbis of the Mishnah spent the Seder night. Did these “wise sons” study the halakha of the Pesach sacrifice, or retell the aggada of the exodus? The disagreement is really a debate over how to preserve and convey the essence of the Jewish experience. Through law or narrative, legal reasoning or theology? This tension is present in the earliest rabbinic texts, carried forward in the positions of the later great halakhic authorities, and is still present at our own Seder tables.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Religious Freedom and Jewish Experience

Religious liberty is back on the Supreme Court’s docket. The court should think carefully about what freedom of religion really means in different communities. Take Jews for instance . . .

The Many Dybbuks of Romain Gary

Romain Gary—a Lithuanian Jew who regarded himself a Frenchman par excellence—emerges in a recent memoir as a master of self-invention and (just as immoderate) verbal invention, a chameleon of pseudonyms, a man of irreconcilable contradictions, divided against himself.

Revolution, the Jews, and Hitler’s Munich

How did a Jewish Socialist become the revolutionary leader of the People’s State of Bavaria? And did his brief career provoke the rise of Hitler?

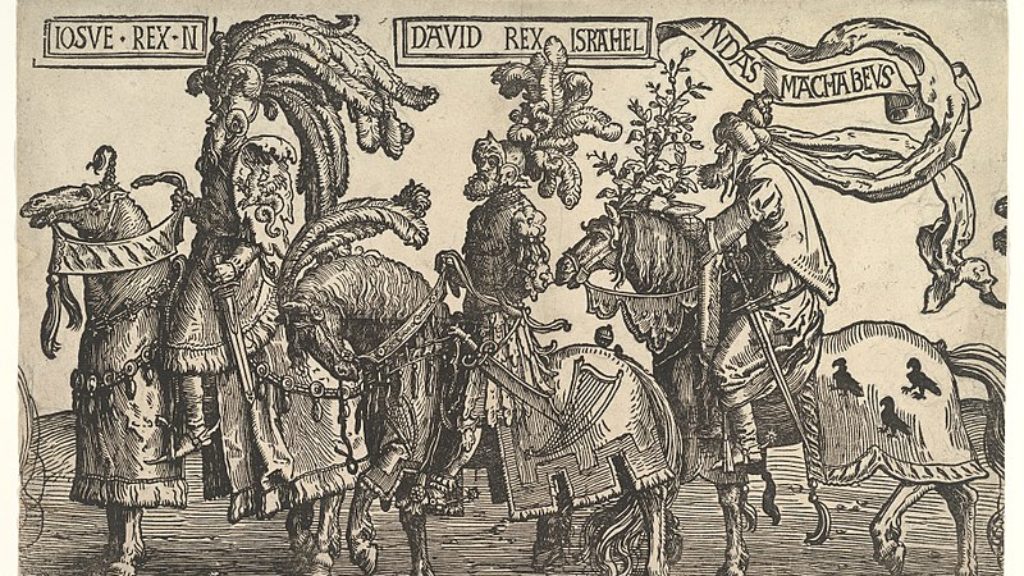

In Memory of Judah Maccabee

That Judah, the great victor of the Hanukkah story, ultimately died fighting the Seleucids is something that surprisingly few Jews know. And were the Maccabees actually underdogs?

rector

Reb Chaim, you are more than a law professor, you are a professor of the law. Chazaq u'varukh "I draw strength from your blessing". The Hagada is ideally collected in the Jewish library we conventionally call The Siddur; hagada is liturgy. I think the Mechaber (Yosef Karo) and the Tosefta agree on this. The Mishna is also a liturgy, I think, but it is "folk-lawful" rather than folkloric. The Siddur emphasizes an ethic, the Mishna a judgement. The ethic is generally more accessible; the judgement is accessible, but to fewer people. Thank you for teaching me and making me a better teacher. Chag kasher ve'samae'akh!

Kindest,

Arie

gebl9999

I recommend you read an article by David Henshke in a recent Tarbiz. The distinction between the two approaches to the hiyyuv is analyzed excellently.

freund

I note that my standard Kitzur Shulchan Aruch has bowdlerized the text to 'la-asot et ha seder' rather than 'in order to eat'!