MAD Maus

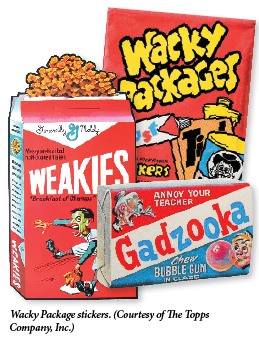

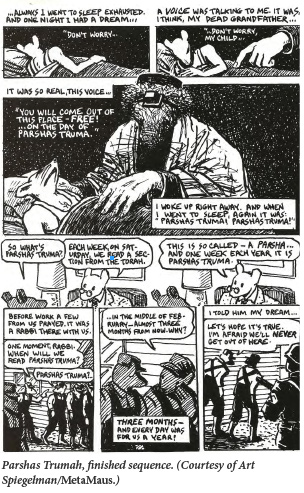

Before Art Spiegelman was a serious graphic novelist, he was seriously funny. Many children of the 1970s remember Wacky Packages, a series of MAD magazine-inspired cards with peel-off stickers that satirized commercial products with cheerfully bad puns and goofy lurid illustrations. The cards were put out by Topps, the leading producer of sports and novelty cards. Wacky Packages were produced by a team of gag writers, cartoonists, and designers, including Spiegelman, who worked for the company from 1966 until 1989, three years after he published the first volume of Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, his wrenching graphic novel about his father’s experience in the Holocaust and their relationship in postwar America, in which Jews such as Art and his father Vladek are depicted as mice and Nazis as cats.

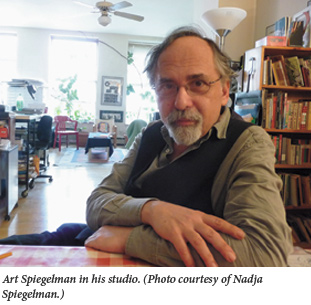

MetaMaus: A Look Inside a Modern Classic, the lavish book of interviews, early sketches, photos, and art related to Spiegelman’s great graphic reconstruction of his family’s experience in the Holocaust, includes some of Spiegelman’s rough sketches for Wacky Packages (“Brandyland Game: More Fun than Hopscotch!”) along with his avant-garde underground comics. In fact, it shows that if it weren’t for his work creating lighthearted children’s novelties, Spiegelman would never have dreamt up Maus. There is a direct line connecting his gags to his serious work. Thankfully, the lighter side of Spiegelman’s cartooning output is addressed in MetaMaus, a sort of behind-the-scenes documentary on paper (okay, it’s not all on paper—there’s a DVD too) chronicling the making of Maus.

Its subject matter notwithstanding, Maus is also a celebration of (and formal experiment in) the medium of comics itself. This grows directly out of Spiegelman’s beginnings as an underground cartoonist in the late 1960s, while he was still working as a commercial artist for Topps. The underground comics (or “comix”) movement of that era was obsessed with reexamining the clichés and tropes of an earlier generation: old Disney cartoons, the Marx Brothers, Broadway musicals, pulp novels—it was all grist for the satirical mill.

MetaMaus might as well be called “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Art Spiegelman but Were Afraid to Ask.” It’s all there: Spiegelman’s initial rough concept sketches for Maus, transcripts of his interviews with his father, rejected (or alternate) versions of various scenes from Maus, anti-Semitic German political cartoons from the 1930s (in which Jews were, of course, also depicted as animals). There are also samples of Spiegelman’s non-Maus work, including his commercial work for Topps. We’re also shown a few of his Wacky Packages concept sketches and some of his controversial New Yorker magazine covers.

At the heart of MetaMaus is a mammoth interview with Hilary Chute, who worked as an associate editor on Maus and whom Spiegelman calls his “chief enabler . . . in a project I kept resisting.” The Spiegelman who appears in the interview is not the pen-and-ink Art Spiegelman character we see in Maus. He discusses how he felt telling his parents’ stories through the medium of comics, why he doesn’t want to be seen as “the Elie Wiesel of comics,” and how many misunderstood the book at first. Spiegelman has even (perhaps gleefully) printed the various rejection letters he received from major American publishing houses when initially shopping the book.

Publishers weren’t the only ones who misunderstood what Spiegelman was trying to accomplish. In the 1980s, fellow autobiographical comics author Harvey Pekar “went into attack mode” in the trade publication The Comics Journal, saying that he would’ve been a better son than Spiegelman, who is often portrayed in Maus arguing with his father Vladek. Of Pekar, Speigelman says:

The fact that, as an autobiographical author, he didn’t seem to grasp that there was some distance, some degree of objectification going on was staggering. Pekar was like: ‘[Gasp!] I found Spiegelman out! He was being insensitive to his father!

Literary catfights (as it were) are not restricted to novelists of the non-graphic variety. But the point, especially in depictions of the Holocaust, is worth making.

Spiegelman has become so lionized over the years (Maus is on syllabi from junior high to graduate seminars) that it is useful to be reminded of his love for “lowbrow” culture. As a child, Spiegelman was obsessed with MAD magazine and its founding editor, cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman. It is easy to look at Kurtzman’s early MAD and see cheap, disposable children’s entertainment. But MAD was the holy grail of subversive kid lit for the generation that came of age during the 1950s and 1960s. A charming 1993 memoir of those years by Spiegelman, titled “MAD Youth,” is included on the MetaMaus DVD. The conclusion to which one is led again and again is that if it weren’t for Kurtzman and MAD, there would be no Maus.

MAD was initially part of a small empire of crime, horror, sci-fi, and humor comics—called EC—that were published by William M. Gaines. The EC titles were filled with preachy morality tales. In MetaMaus, Spiegelman recalls the effect that one 1955 EC story, “Master Race,” had on him while growing up. “Master Race,” published in issue #1 of the EC title Impact, asked what would happen if Holocaust survivors came face to face with their tormentors after the war. Spiegelman points out that this was something “virtually singular in postwar pop culture: a comic about the death camps.” This is striking, and one can only imagine the effect such a comic would have on the child of a survivor in the 1950s. But Spiegelman does seem to be stretching a bit when he says, “I came to think that all the EC horror comics were a secular American Jewish response to Auschwitz but this was the only time it became overt.”

When MAD decided to expand its satirical reach beyond the other offerings on the comics rack, it also decided to “get serious,” engaging in pointed satirical barbs about the Army—McCarthy hearings, juvenile delinquency, and bigotry. It was Swiftian satire aimed at 12-year-olds. For a so-called children’s comic, this was eye-opening, brain-melting stuff! Even while Spiegelman was a young working artist in his years at Topps, MAD remained his lodestar. As he recounts in MetaMaus:

My Topps Bubblegum job consisted of feeding back my MAD lessons to another generation in the form of Wacky Packages, Garbage Pail Kids, and lots of other less successful cards and stickers, sometimes illustrated by the same artists—my childhood idols!—that Kurtzman collaborated with at MAD.

So when Spiegelman decided to devise a comic book about his father’s experiences during the Holocaust, he thought about what Kurtzman would’ve done.

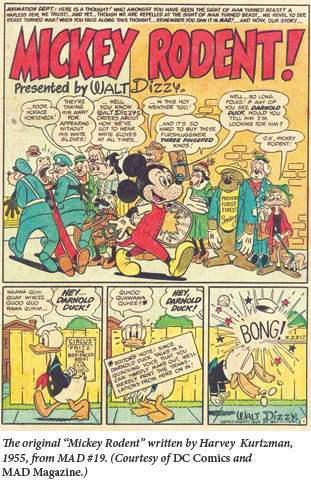

In one of the early issues of MAD, Kurtzman had written a sharp, observant parody of classic Disney cartoons called “Mickey Rodent!” The cartoon not only satirized Disney; it interrogated (as they say in those graduate school seminars) the very idea of talking animal cartoons as well. As Spiegelman recounts in the Kurtzman tribute comic “A Fershlugginer Genius” (first published in The New Yorker and reprinted in MetaMaus) “‘Mickey Rodent’ changed my life.”

Spiegelman succeeded in using the talking animal conceit in Maus. He is both using and undermining this visual tradition. But part of the power of the novel is that one simply forgets that Vladek is a mouse and his tormentors are cats in a way that one never does with, say, Tom and Jerry. (MetaMaus includes pages from Spiegelman’s sketchbooks in which he works out which animals should represent which nationalities: French as frogs, American as dogs, Gypsys as moths, and so on.)

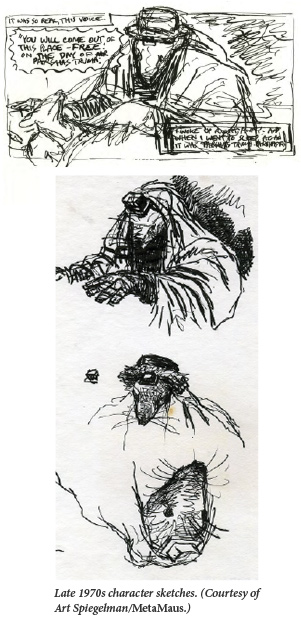

MetaMaus shows us Spiegelman’s thought process throughout the conception and gestation of Maus. Of primary importance are the early concept sketches he drew for Maus when he first started developing the project in the late 1970s. Some of the drawings are comparatively realistic renderings of mice and cats that look like a more disturbing version of Paul Bransom’s classic illustrations for A Wind in the Willows or John Tenniel’s in Alice In Wonderland. Others have a more exaggerated, cartoony look.

One page of MetaMaus consists of no fewer than eighteen different drafts of the same panel, showing young Vladek’s father waking him up and Vladek complaining about lack of sleep. Some are quick thumbnail sketches while others are very detailed and precisely composed. The facing page reveals another three versions of the same panel, culminating in the version of the panel that was published in 1982 as a serial comic book, and finally the version of the panel that was published in book form in 1986.

It is always interesting (and occasionally alarming) to see the artist as viewed by his family, and in an interview Spiegelman’s son Dashiell is quoted as saying:

My dad redraws stuff and rewrites stuff until it’s perfect to him, when other people reading it wouldn’t have noticed anything in the first place. Which in some ways makes me think he’s crazy—and it must be really hard for my mom sometimes, because she has to deal with that—but in other ways it’s really admirable, because it shows he’s doing the work himself.

Spiegelman may have been almost as obsessive when he was sketching Wacky Packages, of course, but one also sees an artist obsessed with his family’s experience in the Holocaust, and obsessed with expressing that very obsession visually. Many who have read Maus may have thought that the book’s scratchy, neurotic, ripped-from-the-sketchbook drawing style was the only way Spiegelman could draw. It isn’t, of course. In MetaMaus, not only do we see early drafts that are very different from what would become Maus, we also see that his more lighthearted cartoons and comics are drawn in a far more antic style, reminiscent of the slapstick images of Milt Gross. “A Fershlugginer Genius” is evidence of that, as are his own contributions to the Little Lit children’s comics anthologies that he edited with his wife Françoise Mouly. Spiegelman’s cover art for one of the Little Lit anthologies is painted in a bouncy, carefree style, one that brings to mind classic children’s books of the prewar era.

In a speech at the Fourth Biannual Comics Salon in Erlangen, Germany for the German publication of Maus (also reprinted in MetaMaus) Spiegelman told his audience that “It’s a strange thing for me as a Jew to be here in Germany, getting an award for describing how your parents and grandparents were accomplices in killing my grandparents and family.” The speech is so cringe-inducing, so unexpected at an awards ceremony, that it almost seems like something Larry David (a morally serious one) would write. And yet, as Dashiell Spiegelman says, he’s doing the work himself, and though it might be impolitic to get up in front of a group of people who’ve just given you an award and call their parents murderers, was he wrong?

|  |

MetaMaus is also revealing about Spiegelman’s writing style. It includes audio files (and transcripts) of the lengthy interviews that Spiegelman conducted with his father Vladek in preparation for Maus. Meanwhile, the MetaMaus book includes some of Spiegelman’s own notebook pages from those interviews, and in wading through this material, we see how he dramatized those interviews, making them work on the comics page. Occasionally he tweaked his father’s dialogue, sometimes making his syntax and grammar more “correct” or easily understandable, but usually for dramatic purposes, and always to make sure that the action was clear.

For many years, Spiegelman taught at Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts (as did Harvey Kurtzman) and in this book he often reverts to “teacher mode.” In both the interview and the art included in the book, we are treated to lessons on how the eye falls on the page, and how certain effects were achieved. In the first volume of Maus, there is a scene in which Spiegelman’s parents are depicted seeing a swastika on a train en route to a sanatorium in Czechoslovakia. (Spiegelman’s mother has just had a breakdown.) The scene is, as Spiegelman notes, an “exact visual rhyme” of a later page in that volume, when his parents first see the gates of Auschwitz. The two pages are composed in a similar manner: In both cases, the first panel shows a small, borderless horizontal shot of a vehicle in motion, the second and third panels are tiered, showing a conversation as through the windows of the vehicle, and the final panel shows a big point-of-view shot (taking up the second half of the page) revealing what the passengers see out the windows of their respective vehicles. “I didn’t expect this to consciously register on most readers,” Spiegelman says, “but assumed it would somehow reverberate anyway.”

There’s much talk in MetaMaus about comics as a medium and its place in the history of art. At one point, Spiegelman is asked which aspects of visual or literary modernism, aside from Expressionism, he’s found productive. His answer is interesting:

I was interested in the fact that us low artists were the keepers of the flame—the only artists still interested in drawing the human figure when all of modernism was moving away from that.

This is both insighful (you can’t explore history without the human figure) and refreshingly unpretentious. For some time now, Speigelman has had pretty good highbrow credentials—but he’s never forgotten his “low artist” roots, making MAD-inspired Wacky Packages for a bubblegum novelty company and underground “comix” on the side. He could never have produced his two searing books about a father and son grappling with the horrors of the Holocaust without them.

Suggested Reading

Jerusalem in Albion

The inclusion of Hebrew manuscripts was a priority for Thomas Bodley in 1598, when he began turning the university’s library into the institution of international and historic renown that would bear his name.

Thoughtlessness Revisited: A Response to Seyla Benhabib

In The New York Times, Seyla Benhabib took issue with Richard Wolin’s critique of Hannah Arendt. Wolin responds.

For the Many, Not for the Jew

The anti-Zionism embraced by far-left activists who flocked to Labour after Jeremy Corbyn’s election has merged with ancient European Jew-hatred to create a new and virulent strain of anti-Semitism.

Something Was Missing

When it was time for new MK Ruth Calderon to speak to Knesset for the first time, she told a Talmudic story and created a YouTube sensation. Her book has now been translated.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In