Jerusalem in Albion

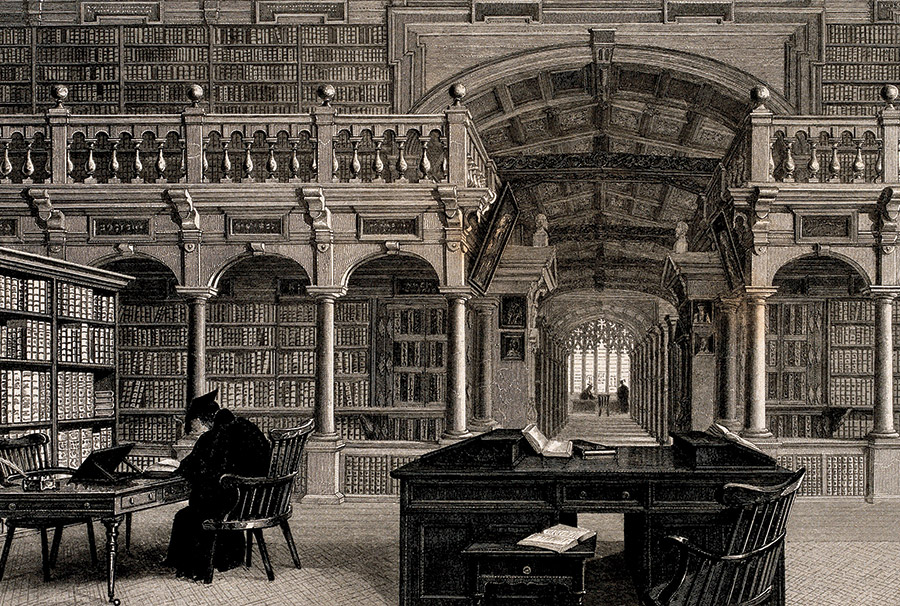

In the spring of 1613, the great European classicist Isaac Casaubon had a brief stay in Oxford, where he spent most of his time reading and conversing with other scholars in Duke Humfrey’s Library, the old creaking reading room of the Bodleian. As Joanna Weinberg and Anthony Grafton told us in their book, I Have Always Loved the Holy Tongue, of particular interest to Casaubon was the library’s rich resources of Judaica and Hebraica. “Among the Hebrew books that I saw in the Bodleian library was the Arba Turim, which is titled Sefer Arba’ah Turim le-rabbenu Yaakov ben Rabbenu Asher zal,” he wrote, and on the same page of notes made reference to the Talmud, Maimonides, and Isaac Abravanel.

Casaubon also mentioned in his diary the hours he spent studying Hebrew texts “with a Jew, a most learned man, whom I found here.” The Jew was Jacob Barnet, an Italian-born scholar who, during his time in that great city of spires, had several Gentile chavrusas, or more accurately, talmidim, in the study of Hebrew. The Scottish physician, poet, and humanist Peter Goldman wrote of his time studying with Barnet:

As boys need the help of a nurse when they learn to walk, so, when I totter, the Jew holds me up; when I fall, he lifts me; when I am running into the wall, he changes my course. To confess the whole truth, he is everything to me. Believe me, this language is harder than I suspected. Some parts of it are impenetrable, and many points require hard work, a fair number of them require intelligence, and a great many require the presence of a teacher.

But in the fall of that year, things turned sour for this learned Jew. After having committed to convert, much to the excitement of Oxonian society, Barnet skipped town the day before his scheduled baptism, only to be caught, thrown in prison, and threatened by the Bodleian’s librarian with punishment “by the custom of our ancestors.” His unlikely release months later was probably due, at least in part, to the lobbying of his former students, including Casaubon and Goldman, although the latter ultimately “renounced his friendship.” Barnet was banished from the kingdom in 1614, the year of Casaubon’s death.

While this story was playing out, the Bodleian was undergoing a major expansion. Between 1613 and 1619, three wings containing three floors each were built to form the library’s iconic Schools Quadrangle with the Tower of the Five Orders at its entrance. In the 1930s, the university erected the eleven-story New Bodleian Library, which was connected to the Old Bodleian by a tunnel and conveyor system underground, where the majority of its stacks sat. The building has since been refurbished and renamed the Weston Library. Today, it still doesn’t have nearly enough space to hold its well over twelve million items, most of which are housed at massive offsite storage facilities.

As César Merchán-Hamann makes clear in his introduction to Jewish Treasures from Oxford Libraries, a handsome volume of coffee-table size, the inclusion of Hebrew manuscripts was a priority for Thomas Bodley in 1598, when he began turning the university’s library into the institution of international and historic renown that would bear his name. Bodley, a Calvinist theologian who died the very year of Casaubon’s visit, was himself an accomplished Hebraist and a committed adherent of ad fontes, the movement of the Renaissance and Reformation to return to the sources of Christian civilization. The study of Hebrew was considered a central pillar of that movement. Fittingly, the first Hebrew manuscript to come into the library’s possession was a copy of the book of Genesis, which is listed among fifty-eight items with Hebrew script in the library’s first catalog from 1605.

Much work has been done on the proliferation of interest in oriental languages in England at this time, and a lot of it was due to William Laud, the indefatigable and zealous chancellor of Oxford who later served as archbishop of Canterbury under Charles I. Beyond establishing teaching positions in Arabic and Hebrew, Laud stressed the identification of Christian England with ancient Israel, particularly as it related to the Temple. As Achsah Guibbory put it in her 2010 book on the subject, “Seeing an unbroken continuity in worship that ran from the biblical Jews through the Church of Rome, he defended the government and ceremonies of the Church of England by reference to ancient Jewish worship.” Calling King Charles “our David,” Laud set about an extensive campaign of church reform that involved centralization of worship and beautification of parishes, “grounded on dreams of imperial glory and religious and national chosenness.” (Descriptions of Laud’s conflicts with the Puritans sound strangely similar to the sections of Tractate Yoma that describe the battles between Pharisees and Sadducees over the appropriate rituals in the Temple.)

The religious tensions stoked by Laud in the seventeenth century would ultimately lead to the English Civil War. Not as lucky as Barnet, he was beheaded on Tower Hill in 1645. But before that, Laud left his mark on the university in ways that few have, including by nearly doubling the Hebrew holdings of the library.

The first person to hold the Laudian Professorship of Arabic, Edward Pococke, is the namesake of one of the Hebrew collections described in the book. Also serving as Regius Professor of Hebrew, Pococke became something of the rosh yeshiva of Oxford in the 1650s and ’60s, guiding “his students through an ambitious course of Jewish literature: Talmud, Mishnaic tractates, literary works such as Judah Halevi’s Kuzari and Benjamin of Tudela’s Itinerary, and the theological and philosophical writings of Maimonides.” Like the final two of these writers, Pococke himself spent considerable time in the Muslim Middle East. At age twenty-five, he became chaplain of the Levant Company in Aleppo, where he perfected his Arabic and developed an interest in Judeo-Arabic. While there, he amassed quite a collection of works in those languages and in Hebrew. His Aleppan copy of Maimonides’s Commentary on the Mishnah contains sections that belonged to Maimonides himself. Pococke used these manuscripts in preparing Porta Mosis, his Latin translation of six Maimonidean essays “and the first book to be printed in moveable Hebrew type in Oxford.”

The jewel in the crown of Oxford’s Hebrew manuscripts is the gorgeous Kennicott Bible, named for Benjamin Kennicott, who served as the librarian of the Radcliffe Camera—perhaps the most identifiable building in Oxford—from 1767 to 1783 and who facilitated the library’s acquisition of the manuscript for what was then a whopping 52.10 GBP. As Theodor Dunkelgrün tells us in his chapter on the Kennicott Collection, this amount was “more than half an average Oxford college fellow’s annual salary at the time.” The Bible is written in a Sephardi script, and though the biblical text itself is beautiful, it is somewhat outshone by the brilliance of its rich illustrations of complex yet pleasing patterns, zoomorphic figures, and colophons.

Interestingly, as Dunkelgrün puts it, Kennicott “seems to have been entirely uninterested in those artistic aspects of the manuscript that scholars now find most compelling.” His central preoccupation was comparing as many versions and editions of the Bible as possible to determine the “inerrant, original Hebrew text of the Old Testament.” Over two decades, Kennicott recruited researchers and financial supporters from across the world, some of whom held directly conflicting political allegiances. (For example, he received support from King George III and American Revolutionary general Christopher Gadsden.)

Dunkelgrün tells us that this was both a labor of love and a labor in love. He writes of Kennicott’s wife, Ann:

[She] learned Hebrew expressly for the purpose of aiding her husband’s research. Almost entirely absent from histories of early modern biblical scholarship, Ann Kennicott’s vital role in her husband’s life and work was recognized by her friend the evangelical woman of letters Hannah More, who would remember that “she was to him hands, and feet, and eyes, and ears, and intellect.”

If the Kennicott Bible is the individual jewel of Oxford’s manuscripts, the Oppenheim Collection as a whole is the Hope Diamond. It contains 5,500 items, the result of Rabbi David Oppenheim’s expressed desire “to own a copy of every Jewish book.” Oppenheim was chief rabbi of Prague in the early eighteenth century, and Joshua Teplitsky’s excellent chapter on the collection is a slimmed-down version of his prize-winning book, Prince of the Press: How One Collector Built History’s Most Enduring and Remarkable Jewish Library. Evidently, Oppenheim defined “Jewish book” rather liberally. As Teplitsky shares with us, almost in a whisper, “Oppenheim possessed various tracts of Shabbetai Zevi’s leading theorists and followers, even though this literature was roundly condemned by rabbinic authorities of his time.”

Oxford’s purchase of Oppenheim’s library, ninety years after the owner’s death, as well as that of the businessman Heimann Joseph Michael’s collection twenty years later, were events of some controversy for the Jews of Ashkenaz. As European Jewish life and culture were transformed by emancipation and the Haskalah, many Jewish reformers, including Leopold Zunz, the father of the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement, considered great Jewish libraries to be necessary resources in the reordering of Jewish political, social, and intellectual life. But in both instances, German Jewry failed to secure the funds necessary to hold on to these treasure chests. In the case of Oppenheim’s collection, Oxford snatched it up for a meager 2,080 GBP, less than 20 percent of what Moses Mendelssohn had valued it at decades earlier.

The Oppenheim and Michael collections are the only two of Oxford’s named Judaica collections to have been assembled by Jews, and while their uprooting from Germany may have seemed a tragedy at the time, it was almost certainly a blessing.

The “discovery” of the Cairo Geniza, the eclectic, centuries-old repository of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat, is mostly a story about Cambridge, not Oxford. In 1896, twin sisters named Agnes Smith Lewis and Margaret Dunlop Gibson traveled to Cairo and Jerusalem, returning with two thousand Hebrew manuscripts, which they showed to Solomon Schechter, who was then a reader in rabbinics at Cambridge University. Schechter famously recognized a scrap from the book of Sirach, a lost work of ancient Jewish wisdom literature, and left for Cairo as soon as he could.

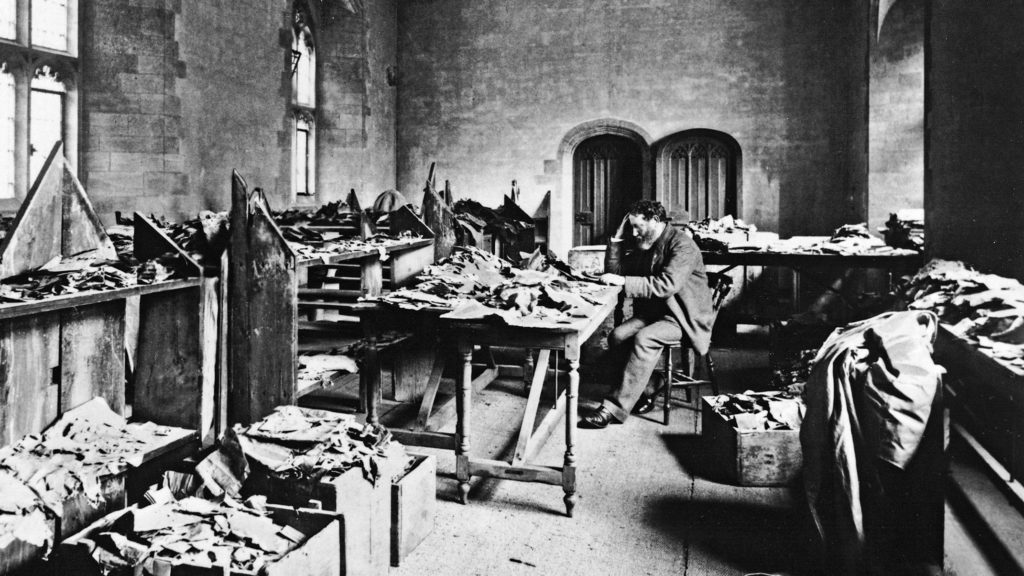

But as Nadia Vidro reminds us, artifacts from the Cairo Geniza began arriving in Oxford several years before the sisters took their trip. The Oxford-trained reverend Greville John Chester, who would winter in Egypt, had come across the synagogue’s archive in 1889 and sent manuscripts to the Bodleian until his death three years later. This early knowledge of the geniza could have led to Oxford becoming the primary destination of its contents, but Adolf Neubauer, Schechter’s opposite number at Oxford, was rather selective, preferring intact works to fragments. Only after Schechter went bullish on the geniza did Neubauer sense the urgency, leading to a rivalry between the two men, and indeed the two universities.

But there is even more to the Cairo Geniza story than has yet been told. In 1883, Neubauer exposed as fake a “coffin of Samson” that had been presented for sale in London. The seller was Moses Wilhelm Shapira, a name increasingly familiar to many outside the world of biblical archaeology and biblical studies due to the controversial new work of Idan Dershowitz, a Bible scholar who now teaches at the University of Potsdam after a stint at Harvard’s Society of Fellows. In addition to the coffin, Shapira claimed to have in his possession the original book of Deuteronomy. Although dismissed as a forgery at the time, the text, which Dershowitz calls “The Valediction of Moses,” is now thought by him and a growing number of scholars to have been authentic. Dershowitz has also found among Shapira’s papers a listing of items “From Ganiza of Cairo.” Shapira killed himself in 1884 and therefore must have been aware of the geniza at least five years before Chester in 1889.

Whichever dealer or scholar was aware of the “sacred trash” first, Vidro excellently selects and describes some of the most important items in Oxford’s Cairo Geniza Collection, including an autographed draft of Maimonides’s Mishneh Torah containing substantial revisions and crossed-out words by the author. While not the only manuscript in the library to contain the Rambam’s handwriting, it is extraordinary. Maimonides led the Jewish community of Fustat in the twelfth century and may have himself placed this document in the geniza.

It is said that the words of Maimonides are golden, chosen to ensure absolute precision, a premise validated by the careful editing clearly visible on this manuscript. At this very moment, yeshiva students throughout the world are cracking their heads to reconcile the apparent contradictions between different parts of Maimonides’s oeuvre, as Reb Chaim of Brisk and countless others have done before them. And meanwhile, this manuscript, which validates the premise of their labor, sat in a forgotten heap for hundreds of years and is now recovered and beautifully photographed for all to see. Is there a truer manifestation of Bava Metzia 42a?

And Rabbi Yitzhak says: Blessing is found only in a matter concealed from the eye, as it is stated: “The Lord will command blessing with you in your storehouses” (Deuteronomy 28:8). Rabbi Yishmael taught: Blessing is found only in a matter over which the eye has no dominion, as it is stated: “The Lord will command blessing with you in your storehouses.”

After the shuttering of physical libraries during the pandemic, and as library budgets continue to shrink, it is right and good to remember the debt of gratitude we owe the great libraries and librarians for preserving our historical treasures—not to mention all those who brought this fine book into being. With the help of the Polonsky Foundation, the Bodleian is working on a digitization project to make its gems even more accessible to the wider public. May it come to be, speedily and in our days.

Suggested Reading

A Book and a Sword in the Vilna Ghetto

If the destruction of Jewish culture and Jewish life were intertwined, then the reverse was also true: The rescue of books, manuscripts, Torahs, and so on was almost as much a form of resistance as the preservation of life itself.

Buried Treasure

Hundreds of thousands of Jewish manuscripts were redeemed from Egypt.

Bling and Beauty: Jerusalem at the Met

In a new exhibit at the Met curators Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb wear their liberal hearts on their sleeves, imagining that Jerusalem's crowds might yet be resurrected as a convivial medieval pluralism.

Pour Out Your Fury

When the Bavarian government confiscated thousands of books from monasteries in 1803, among them was an utterly unique haggadah.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In