Middle Position

When National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice made Elliott Abrams her senior director for Near Eastern and North African Affairs at the end of 2002, she knew very well who he was and where he stood. “By choosing me,” Abrams writes in his excellent new book:

Rice was choosing someone who had already revealed to her—with my private complaints in 2001 and 2002 about the way the NSC staff was handling Israel—my own views. I was a Bush supporter, a Rice supporter, a “Neocon” and a proponent of the closest possible relationship between the U.S. and Israel.

Rice’s selection of Abrams to be her “Middle East guy” at the National Security Council (NSC) meant that she “was staking out a position: closer to Cheney and Bush and farther from Powell and State.”

Early in the Bush Administration, Colin Powell and the State Department had taken the lead in formulating U.S. policy toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. They did so in the service of a president who had entered office without any great eagerness to address the conflict. Nonetheless, Bush and his team understood that the realities of 2001 did not afford him the luxury of ignoring it entirely. The second intifada was unfolding, terrorist attacks were rocking Israel, and Israeli counteraction generated Arab and European pressure on the Bush Administration to rein in Israel and seek a diplomatic solution to the crisis. President Bush’s relationship with Israel’s new prime minister, Ariel Sharon, was not a particularly comfortable one at that time.

All of this was altered by the transformation of two leaders and the non-transformation of a third. Bush was transformed by 9/11 into the prosecutor of “the war on terror.” In this war Sharon successfully placed himself and his country on the right side. Through a larger change in his orientation and policies, he managed to transform himself from the controversial leader of the radical right to a far-sighted, centrist leader, who gradually steered Israel out of a major crisis by defeating the second intifada. Meanwhile Arafat became associated in Bush’s mind with the wrong side, especially after he was caught red-handed in the act of importing weapons on the Karine A and lied about it to the president. One could disagree with or sometimes even annoy the president, but as Sharon realized, you had to maintain his trust. In short, Sharon and his team managed to build a close working relationship with the Bush White House despite an unpromising beginning.

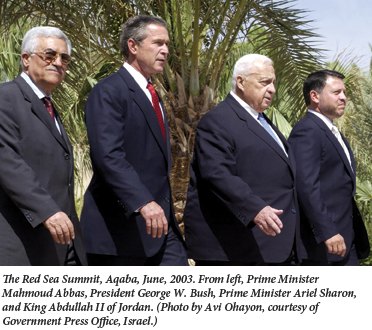

Between June 2002 and April 2004, with Abrams assisting Rice at the NSC, the United States spelled out a policy that supported the establishment of a Palestinian state as the last phase of a process through which the Palestinians would have to abandon terrorism, fight corruption, and build a more democratic political system. In time, Bush and his team also came to the conclusion that in order for this to happen, Arafat would have to be removed from leadership. They did manage to force him to appoint Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen) as prime minister, but Arafat was powerful and devious enough to foil their efforts.

By 2004 it became clear to Sharon that more substantial progress toward a political solution was required. His own political views had changed; he now believed that it was no longer feasible for Israel to control the West Bank and Gaza and their populations. Since he also did not believe that a final status agreement with the Palestinians was possible, he developed instead a policy of unilateralism. Israel would dismantle its settlements in the Gaza Strip and withdraw from it, and at a later phase would go through a similar but more modest exercise in the West Bank. This was not the political solution that the U.S. envisioned, but it decided to support Sharon’s decision nonetheless. In Israel itself Sharon’s disengagement from Gaza was deeply controversial. The right wing criticized it vehemently as both silly and treacherous. The controversy forced Sharon to leave Likud and form a new centrist party, Kadima.

Even before Elliott Abrams assumed his new position at the end of 2002, he was an “enthusiastic supporter of the new Bush approach” to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, including the idea of a two-state solution, and remained one. But he was also a supporter, if less than a completely enthusiastic one, of Sharon’s 2004 disengagement plan, which he saw as not much more than “the only game in town.” He describes approvingly the way that the White House rallied to Sharon’s support when he faced severe difficulties. After Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza, however, and after Sharon’s disappearance from the scene, Abrams found himself increasingly at odds with his own government’s policy and that pursued by Sharon’s successor, Ehud Olmert.

By then Secretary of State Rice’s sympathy for Israel had been steadily diminishing, and her

readiness to exert strong pressure on it was increasing. Why? In part on account of its weak performance in the Second Lebanon War, which apparently shook her confidence in the country’s ability to handle its own affairs. But her move from the White House to the State Department made a big difference too. Unlike George Shultz and Henry Kissinger, Abrams argues repeatedly, Rice did not pull State in her direction but rather was taken hostage by the bureaucracy she should have led:

To put the point more sharply, her Middle East hand at the NSC had been me; now she was getting information and advice from officials whose entire careers had been spent in the Arab world. Now Rice’s advice came from officials of the Near East bureau, at home and in the field.

Even more important than Rice’s malleability was her ambition to bring about an Israeli-Palestinian fnal status agreement as the crowning achievement of her tenure. Unlike President Bush, who “was already comfortable, in 2008, with his place in history,” Rice was, Abrams writes, “still trying to make her mark and time was running out, so a Middle East peace agreement was an important goal.” And there may have been more to it than that. On one occasion Abrams heard Rice compare the state of the Palestinians in the West Bank to that of the Blacks in the segregated American South. If he kept silent when she made this analogy it was apparently because in the end he “did not view the comparison to segregation as an expression of her fundamental view on Israel or of the Arab-Israel conflict but rather as the product of growing frustration.”

With Rumsfeld gone, Cheney weakened, an accommodating NSC director in her former deputy Stephen Hadley, and with the president’s deep trust, Rice came to dominate U.S. foreign policy. And she used her power to push consistently for a final status agreement brokered through active U.S. mediation. This led to strong tensions with Ehud Olmert, whose own conduct of his country’s affairs was, in Abrams’ assessment, deeply flawed. Abrams is highly critical of Olmert’s attempts to interpose himself between Rice and President Bush and of his willingness to offer, in the end, massive concessions to the Palestinians. “Above all,” Abrams reports, he was led astray by “his own desire to achieve peace and prove that he was a consequential historical figure, not an accidental prime minister who had failed in Lebanon and was mired in corruption charges.” His effort to achieve self-vindication via a “peace breakthrough” was something that “worried not only his closest advisers but also a number of us on the American side.”

Abrams was caught in the middle of all of this. Skeptical of the new policy, he “fought it internally” even as he supported some aspects of it in meetings with Israelis and Palestinians. “I stayed in the game,” he writes, “pushing what I thought was a more realistic path: keep some negotiations going while building up the PA’s security forces so that they could successfully fight terror.”

There are still controversies and question marks surrounding the negotiation between Olmert and Abbas, and Abrams dispels some but not all of them. He argues that Olmert did in fact make an extremely far-reaching offer to which Abbas failed to respond, thus in effect rejecting it. Both Olmert and Rice wanted an agreement, but their relationship remained sour. Israeli politicians undermined Olmert, telling Abbas that Olmert had no mandate to make the agreement, suggesting to him that it would be better for him to wait for the formation of the next Israeli government.

Throughout his narrative and especially in his penultimate chapter, entitled “Lessons Learned,” Abrams sheds important light on the ways in which foreign policy is made within an American administration. He tells us both about the process and the players who made up George W. Bush’s national security team. Wisely, Abrams makes frequent reference to the important book Presidential Command by the late Peter Rodman, who served in each Republican administration from Nixon onward. Rodman focused on the manner in which presidents managed their bureaucracies, dealt with internecine warfare, and placed their own imprint on policy. As an assistant secretary in Bush’s Pentagon, Rodman was critical of the president’s requirement that his lieutenants sort out their differences and present him with a consensual view of policy. Rodman argued that this managerial approach was wrong-headed and that the president should rather choose and decide between contending views.

Abrams’ narrative underlines this criticism. He also shows us in great detail how personal relationships and rivalries shaped policy. He shows how, in Bush’s first term, Cheney and Rumsfeld defeated Powell, and how Rice dominated foreign policy in the second term. Abrams remains loyal to his former boss, Stephen Hadley, but he also shows how Hadley’s deference to Rice prevented the president’s own apparent policy preferences and priorities from being implemented.

More significantly, President Bush himself displayed unusual pliancy when it came to Secretary Rice. Time and again he abandoned his preferences for the policies pursued by Rice. Consequently, Abrams suggests, he abandoned the sound policies of the middle years of his presidency to support a futile effort to seek a final status deal. But one wonders whether Bush himself did not become fascinated by the prospect of following up his controversial policy in the Middle East (Iraq is barely mentioned in the book) with a major Israeli-Palestinian peace accord. Needless to say, his administration didn’t succeed in attaining one.

As Peter Rodman and now Elliott Abrams have showed in fascinating historical detail—and as I know from personal experience—the personalities and management styles of different people produce radically different foreign policy strategies and results. A team composed of Nixon, Rogers, and Kissinger is very different from one composed of Obama, Hillary Clinton, and General Jones. For a country like Israel, understanding the nature of the team and knowing how to work with it is crucial. Israelis, Americans, and others who read Tested by Zion will gain important insights not only into the history and nature of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict but also the inner workings of American foreign policy.

Suggested Reading

Dust-to-Dust Song

Nelly Sachs was 50 years old when she fled the Nazis with her mother in 1940. Few would have perdicted that she would receive the Nobel Prize for Literature twenty-six years later.

Power and the Voice of Conscience: A Lost Radio Talk

On January 19, 1947 a young rabbi named Emil Fackenheim got behind a microphone to give a searing radio address about the Jewish refugees from Europe. He himself had been one only four years earlier.

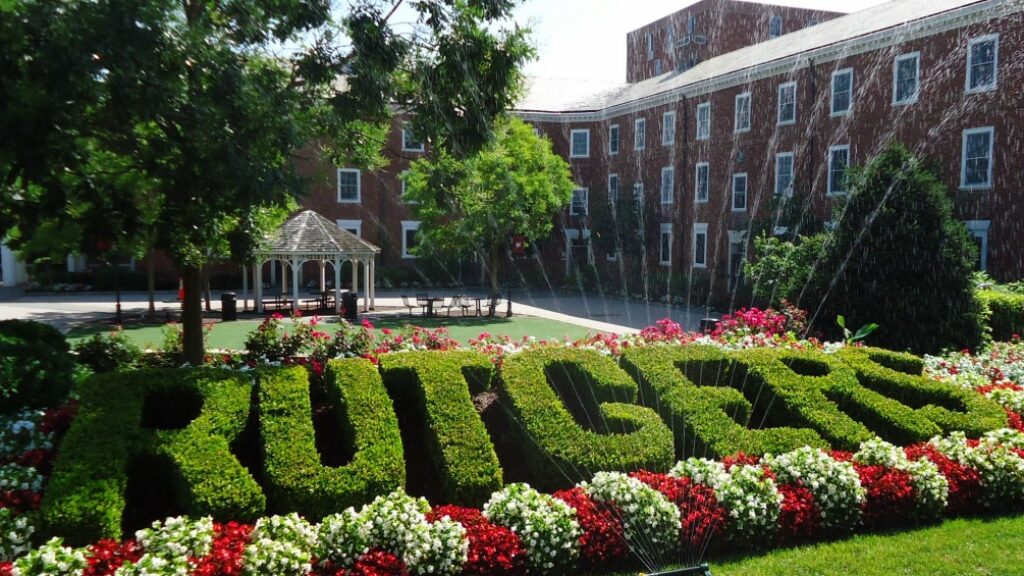

At the Anti-Israel Carnival

Students at Rutgers University protest Israel like they're attending a carnival. A professor explores the troubling scenes she's witnessed—and rereads Mikhail Bakhtin.

Our Kind of Traitor

More than 40 years after the Yom Kippur War, some of its battles rage on, including the debate over the spy Ashraf Marwan’s true loyalty.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In