Dust-to-Dust Song

In 1940, when Nelly Sachs and her mother arrived in Sweden, having escaped the Third Reich only a week before they would have gone to a concentration camp, the idea that she would one day win the Nobel Prize for Literature would have seemed absurd. Pushing 50, Sachs was lightly published, and her poems to that point rarely, if ever, anticipated the force or inventiveness of her post-Holocaust work. Sachs was, to be sure, always a deft writer, but she was not yet a deeply original one.

Legenden und Erzählungen (Legends and Tales), Sachs’ debut, captured the style of Selma Lagerlöf so exactly that it elicited wry praise from her literary idol: I couldn’t, Lagerlöf more or less said, have done it better myself. Sachs’ poetry of the 1920s and 1930s is more original, but hardly unconventional. Her poems from this period appeared in the prestigious Berliner Tageblatt and often featured the motif of the threatened idyll. But they also dealt in neat rhymes, familiar metrics, and a tender handling of animals. When Sachs tried out freer forms, the result was, in the words of her most recent biographer, “epigonal exercises in sentimentality.”

It was only with the publication of her first collection of poems, In den Wohnungen des Todes (In the Dwellings of Death), which Sachs wrote in Swedish exile and dedicated to her “dead brothers and sisters,” that she established herself as an important poetic voice. “Death,” she said, “was my teacher.” The title Aris Fioretos has chosen for his biography is taken from the title of a later collection of poems, but it also describes her literary career.

Fioretos’ elegantly written biography is the first of Sachs to appear in English. Another fitting title from Sachs might have been even more apt: Glühende Rätsel (Glowing Enigmas). Fioretos sees the late work that bears this name as the “high point” of Sachs’ career. Moreover, as much as Fioretos plays up the extent of Sachs’ remarkable transformation in middle age, he seems uneasy with his own conceit. Indeed, he devotes most of his interpretive energy to puzzling over the possible connections between Sachs’ early sensibilities and the poetry that made her famous, to the extent that Sachs became famous. She is well known in Sweden and Germany, but mainly as a figure; her writings aren’t widely read in either country.

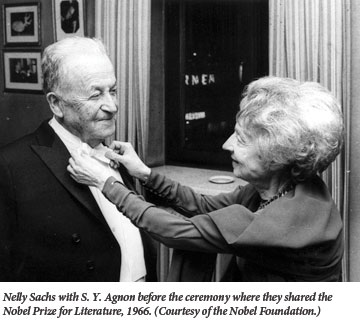

Fioretos spends more than half of the book chronicling the three decades that Sachs, who died in 1970, spent in Stockholm. As befits “an illustrated biography” (it accompanied a traveling museum exhibition and looks like an exhibition catalog), he also lingers here on the material circumstances of Sachs’ life. There are, for example, long descriptions of the tiny apartment where Sachs lived and worked and in which S. Y. Agnon visited her after they were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in 1966. But Fioretos is also skillful in his discussion of the influences on Sachs’ poetry, and their relationship to the many developments in her Sweden years. These included the death of her beloved mother in 1950, which precipitated a breakdown, and her friendship and correspondence with her “brother poet,” Paul Celan. In addition, Sachs was close to many younger Swedish poets whom she translated into German in order to make ends meet, including Tomas Tranströmer, the current Nobel laureate.

During these years she developed an interest in Jewish mysticism. Toward the end of her life she also underwent bouts of paranoia; at one point in the 1960s, she became consumed by the belief that a neo-Nazi terrorist group was responsible for the random noises in her home. Fioretos suggests, imaginatively and not implausibly, that the engagement with mysticism and mental illness were, for Sachs, related. Certainly, the idea that another world inhabits our everyday reality is a crucial motif in Sachs’ late work.

Fioretos’ reflections on what endured from flight through metamorphosis are sometimes less successful. Sachs’ father was an entrepreneur and inventor who created, among other things, “the expander,” a fitness device that worked very much like the strengthening bands of today. (The book contains several reproductions from the expander’s marketing materials.) Having doubted that the contraption helped William Sachs’ nervous daughter, Fioretos speculates that nonetheless “stretching survived as a poetic principle. Lines and cords appear repeatedly in her texts, just as do the expansive veins and arteries of language.” Were it not an unpardonable pun, it would be tempting to call this a stretch. After all, where exactly is the tautness in the illustration Fioretos offers? Fioretos may be succumbing to a hazard of his genre experiment. A biographer who fills the margins of his biography with catalog-style images will naturally want them to play a narrative role.

More often, however, Fioretos is thoughtful and careful in simultaneously reinforcing and complicating the idea of Sachs’ metamorphosis. Perhaps the key event in this effort is the romantic trauma that Sachs experienced in 1908, when she was 17. What exactly happened is unclear; in fact, Sachs refused to disclose the identity of the unattainable object of her adoration, an episode she would repeat twice more. In this first instance, the emotional damage was such that Sachs refused to eat and had to spend more than a year residing in a kind of psychiatric halfway house.

Picking up on Sachs’ cryptic reference to the episode as the “source of my endeavor to take on poetically our people’s greatest tragedy,” Fioretos tries to fill in the space that she left blank—the space between personal woe and collective destiny—exploring at length the loneliness of Sachs’ life as an only child in the well-to-do Berlin home of her assimilated Jewish parents. There were cousins and a couple of dear friends around, and Sachs was extraordinarily close to both her parents, but she also felt a pronounced feeling of “difference” at school, which was exacerbated by the isolation caused by her mental illness. Around 1930, when Sachs was no longer young, she had her second romantic trauma. It was this long-standing loneliness, according to Fioretos, that allowed for Sachs’ intense identification with the Jews, as well as for her poetic project of the 1940s. He stresses that Sachs herself observed after the war, “It is my fate to be alone, as it is the fate of my people.” And without saying when exactly this began to be the case, Fioretos asserts, “Loneliness became the distinguishing mark of [Sachs’] poetry. Without it, no poems.” From there he proceeds to suggest that the “most intimate texts” in the “Prayers for a Dead Bridegroom” cycle, which has been seen as emblematic of Sachs’ metamorphosis, “may actually have been written before the flight.”

To its credit, Fioretos’ lucid, well-researched book never feels hagiographic, despite its abundant expressions of admiration for its subject. About Sachs’ most famous poem, “O the Chimneys,” written in 1947, Fioretos soberly admits “if a poet were to use such imagery today, he would risk counteracting its purpose. The diagnosis would be evident: Holocaust kitsch.” (O the chimneys / On the cleverly designed dwellings of death / When Israel’s body dispersed in smoke.)

If this poem was part of the project for which “Sachs wished to be remembered,” its aesthetic value, in Fioretos’ view, lies in its preparing “the tone for what was to come”—namely, the enigmatic, lapidary late work whose light comes from luminous images:

Mankind, delivered up for so short a time

Who in this case can speak of love

The sea has longer words

and the crystal-spectered earth

with its prophetic form

This suffering paper

already ill with the dust-to-dust song

abducting the blessed word

back perhaps to its magnetic point

which is God-porous

Of course, not everyone will share Fioretos’ literary enthusiasm. For some readers, Sachs’ poetry will go from being too obvious to too obscure.

Her life, with its heartbreak and literary perseverance, is a different story, and it is more likely to resonate in the English-speaking world, where it is newly available.

Suggested Reading

The Fierce Lust for Contemplation

How did traditional yeshivas become fertile ground for radical literature?

Dangerous Liaisons: Modern Scholars and Medieval Relations Between Jews and Christians

In the spring of 1942—which, as Mel Brooks noted, was “winter for Poland and France”—Salo Baron published a boldly revisionist article. He was thinking of present-day Europe, a 12th-century Jewish woman named Polcelina, and perhaps also his colleagues.

One Nation, Two Disraelis

In locating Disraeli within modern Jewish history, the late David Cesarani engages with a tradition that he traces back to Hannah Arendt and Isaiah Berlin, who placed Disraeli’s Jewishness at the heart of his private life, his novels, his political thought, and his career as a politician.

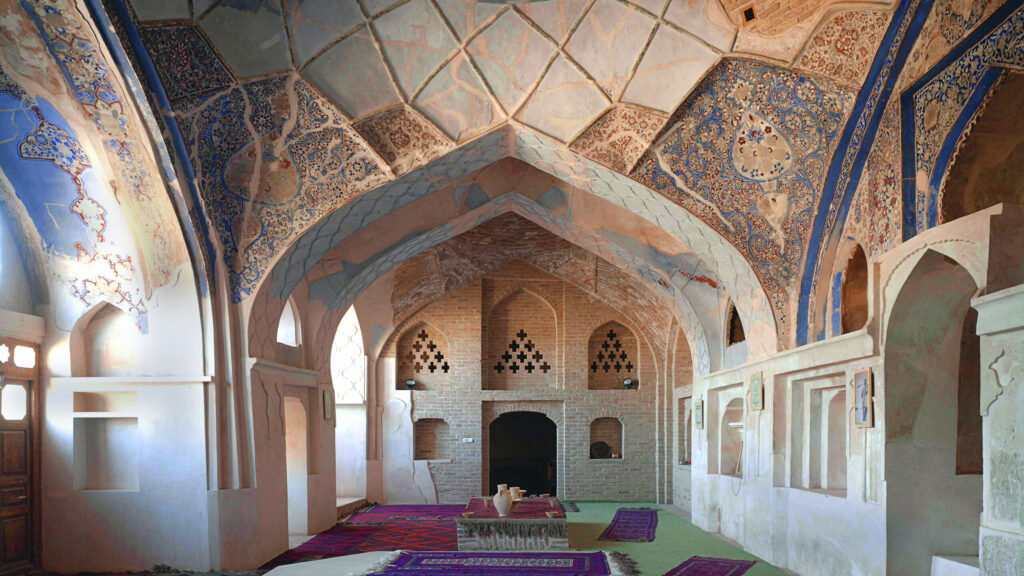

Now a Museum, the Synagogue was Meticulously Restored . . .

The synagogue is a mikdash me’at, a little sanctuary or temple. But what really makes a shul holy and how should they be remembered?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In