Power and the Voice of Conscience: A Lost Radio Talk

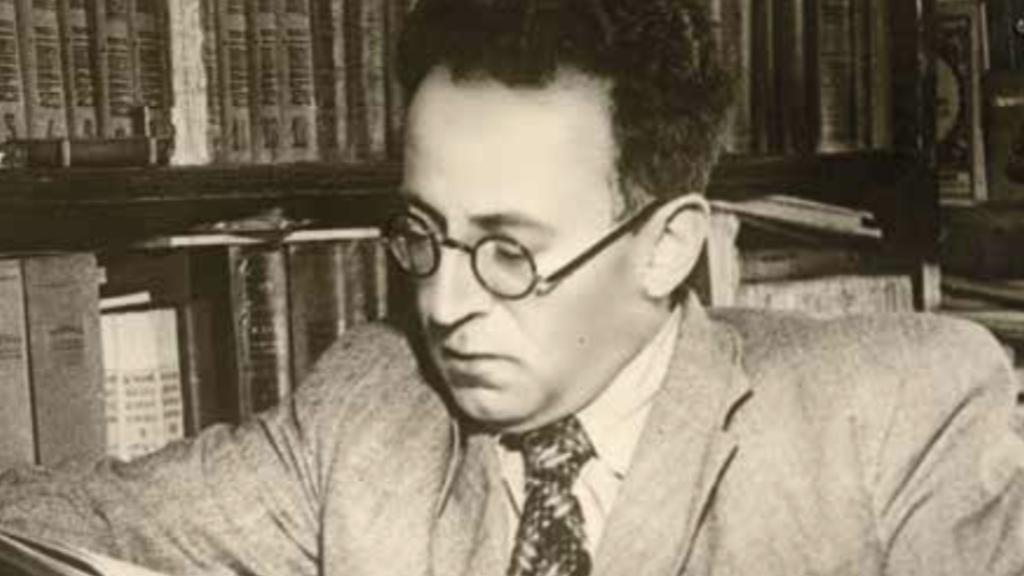

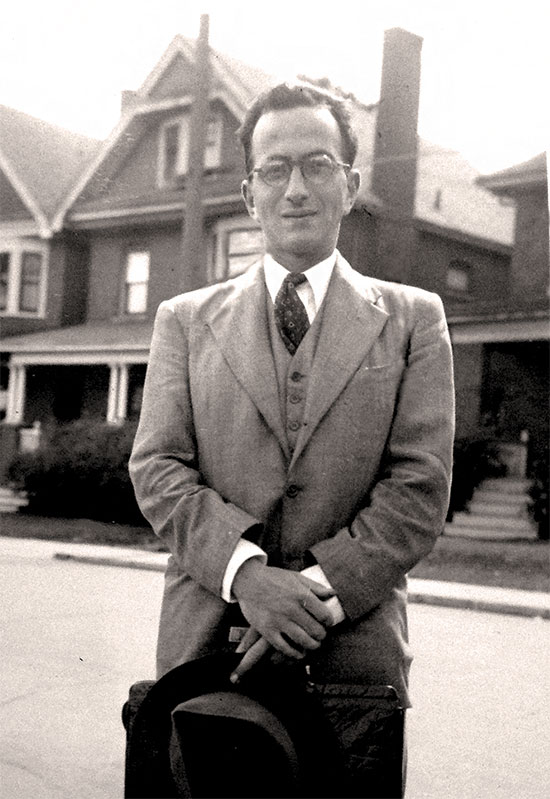

Emil Fackenheim is best known as the Jewish thinker who said that after the Holocaust the Jewish people had received a 614th commandment: not to give Hitler any posthumous victories. But Fackenheim was 50 years old and a widely published philosophy professor before he began to think philosophically and write about the Holocaust in 1966.

In 1938, Fackenheim had been arrested during Kristallnacht and held at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In 1940, at virtually the last moment in which it was possible to do so, he was able to flee, first to Aberdeen, Scotland, and then on to Canada. In 1943, while he was a doctoral student in medieval Jewish and Arabic philosophy at the University of Toronto, he took a position as the rabbi at Anshe Sholom, a Reform synagogue in Hamilton, Ontario. Fackenheim served the congregation until 1948 when he returned to the University of Toronto to teach philosophy. Until recently, little has been known about his thinking in these early years.

Fackenheim’s papers are housed in the National Archives of Canada in Ottawa in 106 file boxes of materials from his youth through his death in 2003. A few years ago, Sol Goldberg, of the University of Toronto, and I spent several days exploring and itemizing what we found. Among the materials that we discovered from this early period were outlines and plans for book projects; a number of graduate student papers and lectures given to philosophical societies on existentialism, German idealism, and Kierkegaard; a large collection of aphorisms; early reviews and talks on medieval Arabic and Jewish philosophy; and more.

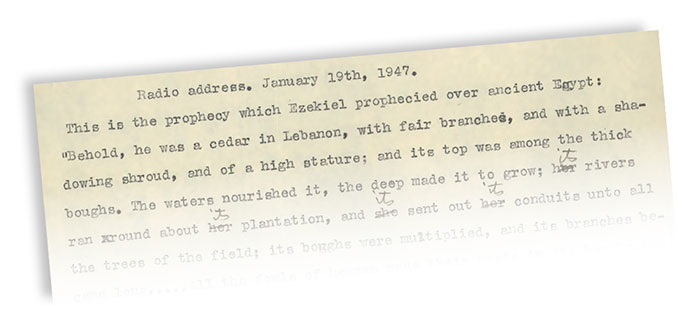

These academic materials are important sources for understanding what Fackenheim was reading and thinking in the 1940s, but they are also more or less what we expected to find. Far more surprising were the typescripts of a series of more than 70 weekly radio addresses that Fackenheim gave on Sunday mornings from 1944 to 1948. It seems likely that the radio talks were revised versions of sermons that he had given on Friday evenings at Anshe Sholom. Although they show a profoundly philosophical and religious mind at work, they were often topical. One, for example, is delivered at the end of the war, another after the communist coup in Czechoslovakia, and a third on the occasion of the San Francisco conference to establish the United Nations in 1945.

Take, for example, the 1947 address printed here. Fackenheim delivered this talk as heated debates were taking place in Canada over what to do about the wartime refugees from Europe. He highlights the tendency to make decisions about immigration policy and quotas based on an economic cost-benefit analysis of how these survivors of the war could serve national interests. On the one hand, “this is understandable; for responsible leaders must have in mind the economic future of the people they lead” but what, he asks, of the needs of the homeless themselves? Such self-interested utilitarian reasoning, Fackenheim warns, risks putting Canada on the path of ancient Egypt as described by the prophet Ezekiel: “a mighty one of the nations” brought low by arrogance and ethical failure.

In radio addresses like this one Fackenheim shows how urgently and continually he felt the impact of Nazism and the plight of its victims, including members of his own family, and its survivors during these years. While he is not yet thinking about the philosophical or theological implications of these events, he cannot put them out of his mind. Interestingly, in this address, Fackenheim speaks as a Canadian rather than as a refugee and survivor. Midway through the sermon he says:

For in these long months since the end of the European war . . . we have refused to give those who became martyrs for us a new home. . . . They are crowded in DP camps, but we have refused to invite them into our wide, near-empty land.

In doing so, he seems to identify not with the victims of Nazism but rather with those in Canada and the United States, who, he says, stood by during the horrors and are still standing by while the survivors suffer, even though he himself was a refugee only seven years earlier.

On the one hand, this may reflect Fackenheim’s natural awareness of his role and his responsibility, but on the other, it may also reflect a reluctance on his part to identify with those who sacrificed so much more than he ultimately had to sacrifice. Having fled and left others behind who suffered through the war and so many, including his own brother, who had been murdered, he, like many survivors, may have been reluctant to think of himself, a lucky one, as one of them. Primo Levi talked about this kind of guilt or shame. Later in life Fackenheim admitted to such feelings, but one may glimpse them here in his striking description of Holocaust victims as “those who became martyrs for us.”

In 1986, when I was planning the collection of Fackenheim’s writings, published as The Jewish Thought of Emil Fackenheim, he asked me to include a short piece called “The Psychology of the Drum,” which I had never read before. He gave me a few typed pages and told me that it was an early unpublished piece that he had given as a talk and of which he remained proud. It is about how members of a civilized and advanced society, of a modern state, can be lured and seduced into the most horrific conduct. In it he recalls the drums of victory after World War I, a war won for democracy, and he also remembers the drums of Nazism, which “can become an evil frenzy destroying the humanity in man” and can “wield millions into a brutal, inhuman machine shrinking back from no crime.”

Until Sol Goldberg and I spent those days in the archives in Ottawa, I did not know where the piece had come from. Now I do. It was delivered in Hamilton, Ontario, on the radio as one of these weekly talks, on Sunday morning, November 11, 1945, a few short months after the war had ended, in the “winter of our discontent.” Fackenheim’s call to his congregation and his radio listeners, to overcome the ghastly drum and the nihilism it serves through acts of justice and mercy, was echoed in many later talks, including this one, delivered on January 19, 1947 and published here for the first time. The text is from a transcription of the original typescript by Yossi Fackenheim, Emil’s youngest son.

This is the prophecy which Ezekiel prophesied over ancient Egypt:

Behold, he was a cedar in Lebanon, with fair branches, and with a shadowing shroud, and of a high stature; and its top was among the thick boughs. The waters nourished it, the deep made it to grow; its rivers ran round about its plantation, and it sent out its conduits unto all the trees of the field; its boughs were multiplied, and its branches became long . . . all the fowls of heaven made their nests in its boughs, and all the beasts of the field did bring forth their young under its branches, and under its shadow dwelt all the great nations . . . all the trees of Eden, that were in the Garden of God, envied it. (Ezekiel 31)

But after having described Egypt in so glowing colors, the prophet goes on to say:

Therefore, thus saith the Lord God: “Because he is exalted in stature, he hath set his top among the thick boughs, and his heart is lifted up in his height; I do even deliver him into the hand of the mighty one of the nations; he shall surely deal with him; I do drive him out according to his wickedness.” (Ezekiel 31)

There can be but few among us who read without discomfort this description of a country rich in fame and material wealth, a country wielding worldwide influence, yet earning for itself the stern condemnation and evil prophecy of an Ezekiel, because as its power grew, its moral fiber weakened. We read it with discomfort, for often we wonder, whether we, part of the most powerful civilization of the modern world, are not on a road leading us to the exact position of ancient Egypt: the combination of maximum worldly fame, wealth, and power with the minimum of moral fiber and moral responsibility. We wonder whether we not evhem. The powerful can even buy themselves free from their conscience. They can construct a propaganda machine persuading them that their selfish or immoral actions are in truth for the good of all. And the voices that tell otherwise are too weak to be heard.

Few, if any, of the great powers and empires of history could withstand the temptations of wealth and power. Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Persia, and Rome—they all went down because of moral disintegration, corruption from within, a failure of moral creativity, apathy towards the mission imposed upon them by their influence—these were the reasons why none of them lived up to the historic task they might have fulfilled: to unify the world of their day, to bridge the barriers between civilizations, to elevate those under their influence to a higher level of moral standards and happiness.

Has our civilization reached a similar critical point? Is our conscience and our sense of moral responsibility growing weaker the greater our wealth, our power, and our influence become? Our modern Western civilization is perhaps the first in all of human history that started and developed under happy moral auspices. It is the first, at any rate, which from its very inception was built on the biblical doctrine that all men are created equal and that their relations must be built in justice and compassion. It has inherited, therefore, a stronger moral fiber than any other previous civilization. Yet there are grave indications that, under the temptation presented today by wealth and power, we are discarding our moral heritage, ignoring the moral responsibilities deriving from our world position. There are indications that we are going along the fateful path of ancient Egypt.en now, while we are as yet unaware of it, stand guilty in the sight of God and in the sight of History.There is nothing strange or paradoxical about the combination of wealth and power with moral guilt. For two reasons, it is an almost natural combination. In the first place, the greater the power of a nation, the greater its influence, and the greater its influence, the greater its moral responsibility. A small nation can do little harm and not too much good. But everything done by the powerful is of tremendous influence, for good or for evil. But, alas, the growth of power does not involve of itself a growth in moral responsibility. In the second place, power brings its own temptations. Selfish lusts grow the stronger, the less there is to stop t

Let us, by a few examples, search deeply into our moral integrity. There can be, today, not a single Canadian or American unaware of the fact that there are in Europe hundreds of thousands of displaced persons. No one who can read a newspaper or understand a newsreel can plead ignorance of the fact that these persons are starved, homeless, insecure, through no fault of their own. I say through no fault of their own. I might say partly through our fault. For they have undergone the most horrible persecution and suffering partly because we were too slow to resist the evil tyranny of Nazi persecution, partly because we were too callous to provide a haven for them when there was yet time. Millions were done to death.

Today, many months after victory, the wretched few who survived the gas chambers and concentration camps still are homeless. They are still surrounded by the enmity of those whom Hitlerism has so dehumanized that they would callously send a Jew to death to steal his store or his home. These people are, in as real a sense as can ever be imagined, carrying on their shoulders the sins of other men. There they are, accusing symbols of the injustice, the cruelty, the calumnies of men in the twentieth century, and their very existence cries accusingly to Heaven—accusing those who caused it to happen, who fanned the flames of hate and brutality, and those who did not resist evil as they could and should have done.

What are we doing today to make up for our sins? It appears that we do nothing, or as good as nothing. We utter a few words of sympathy and perhaps send a few dollars for temporary relief of the impoverished. But in the light of what we could and should do, our words of sympathy sound hypocritical, and the relief we give looks like an attempt to buy ourselves free from the accusations of our consciences. For in these long months since the end of the European war, we have refused to do the only thing that will help, the only thing that perhaps may get us a pardon for our sins in the sight of God and of history. We have refused to give those who became martyrs for us a new home with us, a home where they can live among friendly people, pursue a vocation, create a future for their children. They are crowded in DP camps, but we have refused to invite them into our wide, near-empty land. They continue to be on the brink of starvation, yet we have refused to share with them our affluence.

How can this be explained? How is it that the people of this northern continent, not normally callous and indifferent to the voice of conscience, have behaved in this matter so callously and unjustly?

It is because our growth in power, wealth and influence has made us selfish and self-righteous, and because it has, at the same time, enabled us to

quieten the voice of our consciences.

How do we quieten its voice? We say that the question of immigration must be viewed from the viewpoint of the benefit or harm it may do to Canada. But what is Canada other than its people? Do we mean, then, that we object to saving lives because to do so might mean a slight and temporary burden for each Canadian? Do we mean that there is a single Canadian so callous and selfish as to refuse to, say, give up two or three cents of his annual earnings for two or three years for the salvation of hundreds of lives? I trust that there is no Canadian so callous, so far degenerated from his religious and moral heritage.

The trouble is that we do not put this question in this way. We pretend that it isn’t for our sake, but that of a mysterious entity called Canada, existing apart from its people, that we keep our borders closed. But Canada is not more and not less than its people, and he who loves his country will show this love best by raising her, in his own person, to a higher level of justice, compassion, and decency.

Some of us are in favor of immigration, provided that it is selective. Selective according to what principle? Selective, my friends, according to the needs of Canada, that is to say, our needs. Partly, this is understandable; for responsible leaders must have in mind the economic future of those whom they lead. But surely some consideration should be given in this selection not to our needs, but to the needs of the homeless themselves! Unless we give some consideration to them and much more than we have done, we shall be hypocritical if we open our doors to larger immigration with the feeling that we do so out of justice and a feeling of compassion. By excluding the needy because they are needy, we shall give proof that we care not for their suffering, but for our self-interest, that we are not concerned with eliminating European suffering, but with using European talent for our own enrichment.

We have dwelt on this one example. We might have selected many examples showing that we are today in the same danger in which ancient Egypt was and which the prophet Ezekiel pointed out; our wealth, power, and influence are growing, but our moral responsibility and moral strength are not keeping pace with them. Many educators and religious leaders are realizing this and grow concerned about it. And the more they love their people, the greater their concern. For anyone knowing what human affairs are like knows beyond a shadow of a doubt that the greatness and happiness we all seek for this country will come to chaos and misery, unless justice, decency, and compassion wax stronger and stronger among our people.

Anyone therefore who wishes true greatness and happiness for Canada must fearlessly expose the moral shortcomings of its people—starting with himself. Let us, today, look at ourselves honestly, asking: Am I good enough? Am I selfless enough? Do I esteem justice higher than my own self-

interest? Do I regard my neighbor’s starvation as more serious than my own inability to afford certain luxuries? By so searching our consciences, we shall begin to make ourselves better and happier men. By acting according to this search, we shall begin to make ourselves better and happier citizens, and our countrymen truly great, wealthy, and good. For this we shall do the only thing which can prevent our country from walking along the road of ancient Egypt, Babylonia, and Rome: the road of unscrupulous power, irresponsible wealth, and influence exploited merely selfishly, that road which, as all prophets warned, leads to decay, misery, and chaos.

Suggested Reading

Memories of Morocco

In the 1940s Moroccan Jews were still sacrificing a bull on the Sultan’s doorstep. There was a deep cultural symbiosis of Jews and Muslims in North Africa.

Tangled Truly

Letters of ink. Letters of the heart.

Spiritual Survival

In 1960, the novelist Vasily Grossman wrote to then-premier Nikita Khrushchev with an unusual intention. He wished, he wrote, to “candidly share my thoughts” with the most powerful man in a country that often murdered bearers of candor.

In Pursuit of Wholeness: The Book of Ruth in Modern Literature

While not the most dramatic of all the biblical stories, the quietly moving book of Ruth, which we read on Shavuot, continues to resonate in Western literature.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In