Letters, Summer 2024

Marginally Nabokov

Thank you for Allegra Goodman’s excellent review of Maya Arad’s newly translated collection of novellas, The Hebrew Teacher (“Od Tireh, Od Tireh . . .,” Spring 2024). I loved these stories. The title novella, in particular, reminded me of the novel Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov. Nabokov’s titular main character is also an overworked, underappreciated émigré adjunct language instructor. Like Ilana Goldstein, Pnin has a colleague in French literature who prefers prestige to knowledge: Professor Blorenge “disliked literature, and had no French.” There is also a chair of the German Department whose aesthetic objection to Buchenwald’s location “in the beautifully wooded Grosser Ettersburg, as the region is resoundingly called,” sounds a bit like Yoad Bergman-Harari’s proudly “problematic” embrace of Heidegger:

It is an hour’s stroll from Weimar, where walked Goethe, Herder, Schiller, Wieland,

the inimitable Kotzebue and others. “Aber warum—but why—” Dr. Hagen, the gentlest

of souls alive, would wail, “why had one to put that horrid camp so near!” for indeed, it was near—only five miles from the cultural heart of Germany—“that nation of universities.”

Much like Ilana Goldstein in Arad’s story, Timofey Pnin ends up marginalized by academic colleagues who totally lack his decency. Both portrayals are absolutely brilliant.

David Lobron

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Heresy or Trope?

In his review of Israelism (“Enlightenment and Conspiracy,” Spring 2024), Yehuda Kurtzer offers a sophisticated gloss on a familiar argument: that contemporary anti-Zionist Jews are ultimately not Jews at all. He insists that this is not his claim, but how else to interpret his essay’s central point, that the film tells a fundamentally Christian story? “The archetype here is Paul,” writes Kurtzer, “who had been the Pharisee Saul until he had a vision on the road to Damascus.” Just like Paul, the film’s central figure, Simone Zimmerman, experiences what is to Kurtzer a “conversion [that] moved her from a self-interested cloud of particularism to a vision of spiritual universalism.” The conversion here is quite plainly away from Zionism and toward Christianity. Is there a more paradigmatic narrative of Jewish betrayal than this one?

The view that anti-Zionists are basically heretical is commonplace in contemporary Jewish communal discourse, where it is generally taken that the essence of Judaism is a concern for the Jewish people and the condition for that concern a commitment to Israel as a Jewish state. But by describing Zimmerman’s journey as a fundamentally Christian one, Kurtzer reveals how much the charge is predicated on the Pauline framework he ostensibly rejects.

To Kurtzer, it is “particularism” and by extension nationalism that embodies the fundamental essence of Judaism against the “enlightened universalism” of Christianity. This account of Judaism is familiar above all from Christian interpretations, where Judaism has always represented an attachment to the material, the legalistic, the communal, and, yes, the particular, as against the universal and the eternal. Until quite recently, however, Jewish thinkers have almost universally rejected this interpretation of their own tradition. If one can hazard to describe a “Jewish view” on the fundamental dichotomy between Judaism and Christianity, it is that Christianity is idolatrous and replaces God with man. To Maimonides, for example, this left Christianity unable to deliver on its own promise, for idolatry always ultimately devolves into a worship of oneself. This basic argument was picked up by various Jewish thinkers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that insisted that it is Judaism, and not Christianity, that can point toward a truly universal ethical code.

Given this history, why has it become so ubiquitous to hear that Judaism’s essential political and ethical insight is to temper “the universal” with an attachment to “the particular”? One reason might be that it offers a helpful framework to shore up support for Zionism in a moment when many are uneasy about the ongoing dispossession and domination of the Palestinian people. After all, if any commitment to “the particular” requires a compromise to the universal, accommodating oneself to such discomfort is both the mark of a mature ethical worldview and a sophisticated Judaism. It also provides what appears as an intellectually rigorous justification for labeling those who dissent from Zionism as traitors to Judaism. This may prove efficacious in policing the boundaries of Zionist institutions. But it requires embracing as the essence of Jewish tradition only its most familiar caricature.

Daniel May

Publisher, Jewish Currents

via email

Yehuda Kurtzer Responds

Daniel May’s response to my review of Israelism is puzzling, in that he attributes to me political and theological arguments that I do not make. I make clear in my review that I am not standing in judgment of the Jewishness of the protagonists in the film; in offering the analogy to Paul, I am trying to make sense of the strange way that Israelism chooses to tell the story of their journey. There was a simpler way to present the problems of Israel education without resorting to conspiracy and a less Manichean way to tell the story of young people who gradually change their politics—that the filmmakers chose a Pauline framework of conversion as the operative analogy is just that, a literary and artistic choice. Making it plain in a review is hardly the same as issuing a charge of heresy.

But the theological argument he attributes to me is downright perplexing. I make no argument at all in my review of the superiority of the particular over the universal, nor do I reify that binary. From the book of Genesis onward, the particular and the universal are interwoven threads; any serious theological teleology requires the interdependence of the story of the Jewish people and the vision we seek for the world. But an interdependence is just that—not a casual or theoretical gesture to Jewish peoplehood for the sake of constantly castigating its moral failures.

Today’s Jewish left talks about Jewish values but cannot formulate a coherent politics around Jewish bodies, especially as relates to the half of whom live in Israel, and this makes them incapable of engaging with the actual Jewish body politic except via nihilistic caricatures like Israelism. Those like Daniel May who understand the shallowness of the film’s argument but want to find a way to intertwine the universal and the particular might take some direction from Martin Buber, beloved for his prestate binationalism, who insisted in his letters to Hermann Cohen that his Zionism entailed the means of preserving of the Jewish people as a necessary precondition of his (and our) universalistic messianic aspirations, and who, unlike his contemporary heirs, accepted the imperfect conditions of statehood as the framework within which to offer moral critique. Some commitment to Jewish particularism is necessary for a plausible commitment to the aspirations of Jewish universalism. There are no shortcuts.

Age of (Jewish) Anxiety

Leon Botstein’s wonderful long review of Bradley Cooper’s mediocre long biopic (“Kaddish for the Maestro,” Spring 2024) sent me back to the New York Philharmonic’s 1950 recording of Leonard Bernstein’s “Age of Anxiety,” with Lukas Foss on piano. It’s marvelous, though also far cheerier than Auden’s bleak tetrameter (“Odourless ages, an ordered world / Of planned pleasures and passport- control”). It occurs to me that Lenny, if I may, was a product not only of postwar American Jewish self-confidence, as Botstein rightly argues, but also of the accompanying American Jewish anxiety. Leonard Bernstein didn’t change his last name to Burns or hesitate to draw on Isaiah as freely as Auden, but he also craved mainstream acceptance.

R. F. Bieber

Los Angeles

Suggested Reading

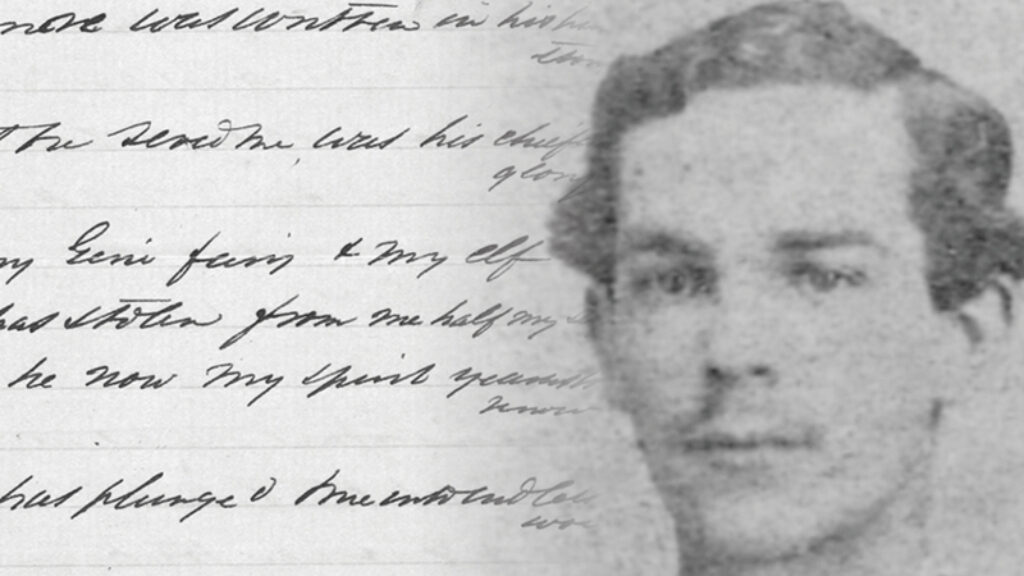

A Savannah Poet

The Civil War cut short many lives, and in a book that blends the genres of history and memoir, Jason K. Friedman sets out the resurrect the memory of one of those lives.

In and Out of Africa

Explaining the origins of the many African and African American groups who identify themselves as Jews or, at least, as descendants of the ancient Israelites.

Swept Up

A new documentary displays the process of conversion to Judaism.

Radical Kindness and Heroic Dogs: A New Anthology of Yiddish Children’s Literature

Honey on the Page, like the best anthologies, is an eye-opening work of literary history, gleefully introducing a sea of lightly known authors through both their work and through meticulously crafted biographical sketches.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In