In and Out of Africa

Ever since the Sorbonne-educated scholar and Zionist activist Jacques Faitlovitch traveled to Ethiopia to visit the Beta Israel in 1904, the blurred boundaries of the Jewish people have been expanding. Increasingly over the last century, Africans, Indians, South Americans, African Americans, and even New Zealand tribespeople have asserted their Jewish identity. Of these, Ethiopian Jews are the best known because their Jewish identity has been halakhically authenticated by the Israeli rabbinate, and the struggling community of about one hundred and thirty thousand Ethiopian Israelis garners a great deal of support in the United States.

Next in order of public awareness are the Abayudaya (“People of Yehuda”) from Uganda. Other African groups who claim Jewish identity include the Lemba of South Africa and Zimbabwe, the Igbo of Nigeria, and numerous smaller groups in Mali, Timbuktu, Cape Verde, and Ghana. Taken all together, these groups number in the tens of thousands.

Two new books set out to explain the origins of the many African and African American groups who identify themselves as Jews or, at least, as descendants of the ancient Israelites. Both books focus primarily on the origins and evolution of these Judaic and black Israelite identities, rather than the practices, doctrines, and lifestyles that they have generated. Black Jews of Africa and the Americas, by Tudor Parfitt, is based upon a series of lectures he gave in 2011 at Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute. Parfitt is famous for his many expeditions in Africa and the Middle East to uncover the lore surrounding the Lost Tribes of Israel. In economical and fast-paced prose, he argues that “Judaized” societies on the African continent are the product of “the Israelite trope”—the belief, introduced into Africa by European colonialists and Christian missionaries, that some Africans are descendants of the Lost Tribes. Parfitt argues that Africans who identify themselves as Jews or Israelites have adopted and internalized this trope as a narrative of their origins.

In the United States, African American Jews—as well as some black Christians and Rastafarians—also affirm their descent from ancient Israelites (although not specifically from the Lost Tribes). In Chosen People: The Rise of American Black Israelite Religions, Jacob Dorman, a young historian from the University of Kansas, traces the threads of American Black Judaism, Israelite Christianity, and Rastafarianism in abundantly documented detail. In a thesis that parallels that of Parfitt, Dorman says that these religions arose in late-19th-century America “from ideational rather than genealogical ancestry.” They are, to use Benedict Anderson’s famous phrase, “imagined communities,” and their leaders “creatively repurposed” the Old Testament, along with the ideas of the Pentecostal Church, Freemasonry, and, eventually, an Afrocentric historical perspective in a manner that spoke to black Americans.

The first Europeans to explore Africa read the Bible as universal history. Thus, they explained the existence of African peoples they encountered by conceiving them as one of the Lost Tribes of Israel. The idea that blacks were Jews was persuasive to them, because as Parfitt writes:

[B]oth Jews and blacks were pariahs and outsiders, and in the racialized mind of Europe this shared status implied that Jews and blacks had a shared “look” and a shared black color.

Parfitt cites the research of a German army officer, Moritz Merker, who studied Masai customs and religious practices in the late 19th century. Merker observed “profound and numerous parallels between the Masai’s myths and customs, social structure, and religion and those of the biblical Hebrews.”

The Bible then was largely responsible for giving the Masai a new racial identity . . . He concluded that the Masai and Hebrews once constituted a single people. The Masai in fact were Israelites.

Parfitt traces how European colonialists and missionaries imposed ideas of Israelite descent upon the Ashanti, Yoruba, Zulu, Tutsi, Igbo, and other peoples across sub-Saharan Africa, prompting a subset of each group to adopt the invented stories of origin as historical truth.

For Parfitt, even the Ethiopian Beta Israel, whose Jewish identity has been granted by the Jewish state, root their Jewish origins in legendary, rather than historical material. The Ethiopians themselves, both Beta Israel and Orthodox Christian, shared a belief in descent from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, based on their own Kebra Negast, a compilation of ancient lore about the origins of Ethiopia redacted about seven hundred years ago. In 1973, when Chief Sephardic Rabbi of Israel Ovadia Yosef halakhically validated their Jewish identity, he based his opinion on the 16th-century responsum of Rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra (known as the Radbaz), who concluded they were descendants of the tribe of Dan. The Radbaz inherited the idea of the Danite origins of the Ethiopian Jews from the unverifiable writing of Eldad Ha-Dani, a 9th-century traveler who himself claimed to be a Danite. Parfitt quotes Henry Aaron Stern, a Jewish convert to Christianity who visited the Ethiopian Beta Israel in the mid-1800s and subsequently reported: “There were some whose Jewish features no one could have mistaken who had ever seen the descendants of Abraham either in London or Berlin.”

The Israelite trope was useful for Christian missionaries. If Africans were the descendants of the Israelites who had accepted the original covenant between God and Israel, what could make more sense than that they would now enter into the New Covenant? Occasionally, however, the missionaries’ efforts took an unexpected turn, when some Africans were drawn towards the Jewish side of their putative Judeo-Christian legacy.

The Igbo Jews of Nigeria are a case in point. An estimated thirty thousand Igbo practice some sort of Judaism, and there are nearly forty synagogues in Nigeria, which follow different Jewish or quasi-Jewish practices. Although their opinions about their tribe of ancestry (Gad, Zevulun, or Menashe) vary, virtually all accept the general Lost Tribes theory and believe that customs of Israelite origin, like circumcision on the eighth day, methods of slaughtering of meat, and endogamy, predated colonialism.

In 1789, Olaudah Equiano, a former American slave who purchased his freedom and moved to London, published a famous and widely read autobiography in which he described similarities in customs between Jews and his own Igbo tribe based on recollections from his childhood. A half-century later, the British Niger expedition of 1841 brought with it letters from London rabbis to the (lost) Jews they expected to find in Africa. By 1860, part of the Bible had been translated into the Igbo language. In 1868, Africanus Horton, an Igbo nationalist educated in London, published a “vindication” of the African race by arguing that “the Igbo could trace their origins back to the Lost Tribes of Israel and that their language was heavily influenced by Hebrew.” Some believe that the word Igbo is derived from Ivri, the Hebrew word for “Hebrew.”

In the late 1960s, the Biafran War of Independence pitted some thirty million Igbo against the much larger Nigeria. The horror of more than a million deaths, most of them Igbo, propelled many more Igbos to identify not only with Jews, but with Israel:

[T]he fact that they [Igbo] were scattered throughout Nigeria as a minority in many cities created the sense of a Jewish-like diaspora, and the “holocaust” of the Biafra genocide provided an even firmer ground for establishing commonalities with Jews. The publicists of the Republic of Biafra compare the Igbo to the “Jews of old” . . . they termed the anti-Igbo riots as anti-Semitic Cossack “pogroms.”

As Parfitt aptly puts it, “Once a myth is established, it often acts as a magnet to the iron filings of supporting evidence: points of comparison and further proofs accumulate and create a consistent, interlocking, convincing whole.”

It has convinced more than the Igbo. Kulanu (All of Us), an American nonprofit that supports vulnerable Jewish communities, has published the writings of Remy Ilona, an Igbo Jew who retells as historical the narrative Parfitt casts as mythic, and a recent documentary film, Re-emerging: The Jews of Nigeria, has brought the Igbo’s story to several Jewish film festivals.

The Abayudaya of Uganda are unique in not claiming descent from a Lost Tribe, but Parfitt argues that they still owe their origins to imported biblical lore. Protestant missionaries from England, which ruled Uganda as a protectorate from 1894 until 1962, evangelized the native population by telling them that “the British themselves had learned this [biblical] wisdom from Oriental foreigners—a people called the Jews. It followed then that if the all-powerful British could accept religious truth from foreigners, so too could Africans.”

Accepting Christianity, together with the idea that Jesus was a Jew, unexpectedly prompted the formation of the Society of the One Almighty God in 1913, which attracted ninety thousand followers who kept the Saturday Sabbath and became known as Malakites (after their leader, Musajjakawa Malaki). More descriptively, they were also known as “Christian Jews.” In 1913 Semei Kakungulu, a Protestant convert and a prominent military advisor to the British in their battles with native Muslims, joined the sect. But the British treatment of Africans angered Kakungulu and he declared himself a Jew, Parfitt suggests, as a protest against the British treatment of his troops. Kakungulu, Parfitt writes, “used his self-identification as a Jew as a weapon.”

Currently, there are about twelve hundred Abayudaya, many of whom have been converted to normative Judaism by visiting American rabbis. The group’s spiritual leader, Gershom Sizomu, was ordained by a conservative beit din in 2008, after he graduated from the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies in Los Angeles.

The Lemba of South Africa and Zimbabwe, with whom Parfitt has been most closely associated, are a complicated case. When he first encountered the Lemba in 1985, they told him that they were “blood relatives” of the Falasha and that they came from a place called Sena, to the north and across the sea. Parfitt quotes several comments by early European travelers on “the lighter skin and Jewish appearance of the Lemba” as well as the “Semitic features of the Lemba.” In 1989, a Lemba woman in Soweto told Parfitt:

I love my people . . . we came from the Israelites, we came from Sena, we crossed the sea. We were so beautiful with beautiful long, Jewish noses . . . We no way wanted to spoil our structure by carelessness, eating pig or marrying non-Lemba gentiles!

Fascinated by the legends, Parfitt spent months on an adventurous search for their Sena, which he documented in Journey to the Vanished City (a bestseller that earned him the nickname “the British Indiana Jones” in the popular media). He didn’t turn up the ancient city, but an unexpected finding published in The American Journal of Human Genetics startled Parfitt into looking further. A DNA study showed that “50 percent of the Lemba Y chromosomes tested were Semitic in origin, 40 percent were ‘Negroid,’ and the ancestry of the remainder could not be resolved.” A set of six markers, the Cohen Modal Haplotype (or CMH) was present in high frequency in both the priestly class of Jews and the Lemba.

In 1997 Parfitt conducted his own testing focused around the deserted ancient town of Sena in Yemen. While it was clearly not the Sena of Lemba legends, Parfitt believed there was a connection between this location and the Lemba “on the basis of [unspecified] historical and anthropological data.” His study showed that the Buba clan (the “priests” of the Lemba) had a high incidence of CMH as did the kohanim. The New York Times, the BBC, and a NOVA television special announced Parfitt’s discovery of this “African Jewish tribe.” Parfitt, however, is more circumspect and suggests that “the ‘Jewishness’ of the Lemba may be seen as a twenty-first-century genetic construction.”

How important is the genetic criterion in determining inclusion in Jewish peoplehood? The Ethiopian Jews, who have also undergone genetic testing, which they decisively “failed,” are an instructive case. DNA testing showed them to be similar to Ethiopian (Orthodox Christian) men rather than to Israeli Jewish men. Yet, they are almost universally regarded as part of the Jewish people, while the Lemba are not. Genetic links seem neither necessary nor sufficient for Jewish identity. Could it be that Israel and the Jewish Federations of North America believe the Beta Israel are descended “from the Tribe of Dan”? Is this the slender thread—one that can bear no historical weight—that authenticates their Jewish identity? Or is it rather their consistent practice over the centuries? Parfitt’s concisely crafted Black Jews in Africa and the Americas is an invitation for us to reexamine the criteria we actually use to determine Jewishness.

In Chosen People, Jacob Dorman defines a “Black Israelite” religion as one whose core belief is that “the ancient Israelites of the Hebrew Bible were Black and that contemporary Black people [in America] are their descendants.” Contemporary practitioners of one or another variety of this religion can be found in black congregations in Chicago, New York City, and Philadelphia. They generally identify themselves as Jews and Israelites, unlike the Black Hebrews of Dimona, Israel (originally from Chicago), who identify themselves as Israelites but not as Jews. This, of course, does not include the small but significant number of African Americans who have joined mainstream Jewish congregations or who have converted formally.

Like Parfitt, Dorman denies the historicity of the belief in Israelite descent. The earliest impetus to identify with the ancient Israelites was motivated, he says, by a “search for roots among uprooted people.” Slavery had severed African Americans from their history and demeaned their social and economic status. As can be heard in spirituals of the mid-1800s, such as “Go Down, Moses,” blacks resonated with the biblical Israelites as oppressed slaves in need of liberation, and some of them imagined an actual Israelite past for themselves. Christianity was the “white religion” of the slave-owners, while for some blacks, the Israelite religion stood for freedom.

In Chosen People, Dorman rejects the idea that Black Israelite religions flowed only “vertically” from roots in the past. “People also pick up culture more obliquely or ‘horizontally,’” he writes. His preferred metaphor is the rhizome, a plant fed by “subterranean, many-branching, hyper-connected networks.” Black Israelite religions, then, were created from a “host of ideational rhizomes”: biblical interpretations, the American passion for Freemasonry, the Holiness church, Anglo-Israelism, and Garveyism. The power of Dorman’s sometimes sprawling narrative derives from the way he shows how these disparate strands became interwoven.

The two principal founders of Black Israelite religions, William Christian (1856-1928) and William Saunders Crowdy (1847-1908), were both born into slavery. Both of them first became active Freemasons, and Dorman sees this as one source of the new American religion they would found. “It is likely,” he writes, “that Masonic texts as well as Masonic interest in the Holy Land and in biblical history helped both men to formulate their Israelite beliefs.” William Christian preached that “Adam, King David, Job, Jeremiah, Moses’s wife, and Jesus Christ were all ‘of the Black race,’” and emphasized racial equality before God.

[Christian] referred to Christ as “colorless” because he had no human father . . . He was fond of St. Paul’s statement that Christianity crossed all social divisions . . .

Crowdy was passionate and charismatic, but he also had bouts of erratic behavior that landed him in jail. After moving to the all-black town of Langston, Oklahoma in 1891, he was tormented by hearing voices and, during one episode, fled into a forest and experienced a vision compelling him to create The Church of God and Saints of Christ. Influenced by the idea that the ancient Israelites were black, he introduced Old Testament dietary laws, the seventh-day Sabbath, and the observance of biblical holidays. By 1900, Crowdy had opened churches in the Midwest, New York, and Philadelphia. These churches, as well as those founded by William Christian, adhered to the Holiness (later, Pentecostal) tradition. By 1926, Crowdy’s Church of God and Saints of Christ had thousands of followers, and there were more than two hundred branches of Christian’s Church of the Living God.

In Harlem of the early 1900s, the serendipitous proximity of black Americans and Eastern European Jews gradually transformed Black Israelite Christianity. The new leaders of Black Israelism, Arnold Josiah Ford, Samuel Valentine, Mordecai Herman, and Wentworth Arthur Matthew, were all recent Caribbean immigrants who believed that Sephardic Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition had intermarried with West Indian blacks, passing on Jewish customs to their descendants. Not entirely unlike the painters, poets, and musicians of the Harlem Renaissance, these men were artists of the religious experience, creatively mixing an impressive array of ingredients that evolved into Black Judaism, Black Islam, Rastafarianism, and other religious orders:

Black Israelism drew on Caribbean carnival traditions, Pentecostal [Holiness] Christianity, Spiritualism, magic, Kabbalah, Freemasonry, and Judaism, in a polycultural creation process dependent not on an imitation or inheritance of Judaism as much as on innovation, social networks, and imagination.

Marcus Garvey’s elevation of Africa to a kind of black American’s Zion became another cornerstone of Black Israelite thought. Josiah Ford, the first Black Israelite to give himself the title “rabbi,” was the music director of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association and even tried to convert Garvey to Judaism. At Garvey’s headquarters in Liberty Hall, Ford, Valentine, and Herman, who had studied Hebrew with their Ashkenazi neighbors in Harlem, taught liturgical Hebrew to other Israelites. Ford, along with Valentine, soon founded the Beth B’nai Abraham congregation, which was the earliest locus of Black Judaism.

Whereas the Holiness Black Israelite founders had derived Judaic practices from Christian and Masonic texts and practices, Ford and his collaborators . . . rejected Christianity and practiced Jewish rituals with Jewish prayer books.

In his re-creation of Harlem of the 1920s, Dorman demonstrates the symbolic importance to black Americans of Ethiopia. Ethiopia enjoyed widespread adulation as the African nation that had never been colonized. The country’s luster was further enhanced by the fact that it was mentioned frequently in the Bible (as the translation of the Hebrew Cush). Thus, the exciting news of Jacques Faitlovitch’s recent encounters with Ethiopian Jews was a windfall that provided Black Israelites with a missing link to both an apparently authentic African Judaism and an African Zion. Ford actually “made aliyah” to Ethiopia with a small cadre of Beth B’nai Abraham members, and Dorman recounts the expedition’s tragicomic misadventures in dramatic detail.

With Ford gone, the mantle of leadership fell upon Wentworth Matthew. It was Matthew who eventually stripped Christianity out of what had begun as a Holiness practice. In Harlem in 1919 he founded the Commandment Keepers Congregation of the Living God, later renaming it the Commandment Keepers Royal Order of Ethiopian Hebrews. He also established a school, which, as the International Israelite Rabbinical Academy, still ordains the rabbis of Black Judaism.

Matthew’s own certificate of ordination, or smicha, was mailed to him from Ethiopia by Ford, and is signed only by an official of Ethiopia’s Orthodox Christian Church. This curious detail is representative of Dorman’s unsparing revelations concerning Rabbi Matthew, and they are sure to raise eyebrows and hackles among Black Jews who revere him to this day as a founding figure. Dorman draws from a wide array of archival documents—he calls them Matthew’s “hidden transcripts”—to indicate a more gradual and ambiguous abdication of Christian and “magical” practices than is commonly believed, though he ultimately does describe Matthew as having “transitioned from ‘Bishop’ to ‘Rabbi’ and from Holiness Christianity to Judaism.”

Chosen People is unique in placing Black Israelite religions in the complex context of American history and is the most comprehensive work of scholarship on this topic, but it is not always an easy read or straightforward. For example, Crowdy’s biography and role are introduced in a dozen pages in Chapter 1, but then much of this material is restated in a slightly different context in Chapter 3. Nevertheless, Dorman’s nuanced analysis of Israelite religion and the dramatic stories he tells along the way make it well worth the moments of déjà vu. No one attempting to understand the rise of Black Israelite religions in America can afford to do without Chosen People.

Like Parfitt, Dorman concludes his book by raising the question of religious identity. He argues that “‘Polyculturalism’ is a better term than ‘syncretism’ for describing the process by which African Americans have created new religions in the twentieth century.” Those who have worshipped at black congregations in the Rabbi Matthew tradition can attest to the accuracy of Dorman’s terminology: The service, siddur, and the Torah reading are virtually the same as those of mainstream synagogues, but the call-and-response preaching, the music, and the religious fervor are deeply African American.

As Black Israelites, these faith practitioners believe they are Jews by descent. Chosen People challenges that historical premise. If, however, one were to ask Dorman whether they are Jewish, I suspect that his answer can be found in the final paragraph of the book, where he challenges the reader “to look at the world, its peoples, and cultures as riotously impure.”

Suggested Reading

Thinking About Revolution and Democracy in the Middle East: A Symposium

Since January of this year, revolution has spread across North Africa and the Middle East with such velocity that predicting exactly what will happen next is probably a fool's errand. In this issue, we have asked seven writers to return to their bookshelves and tell us what books, authors, and arguments they find helpful in thinking through the causes and implications of these surprising events.

The Alter Rebbe

In Immanuel Etkes's new biography, we meet the young Shneur Zalman shortly after the death of his master Rabbi Dov Ber Friedman, known as the Maggid (or preacher) of Mezheritch in 1772.

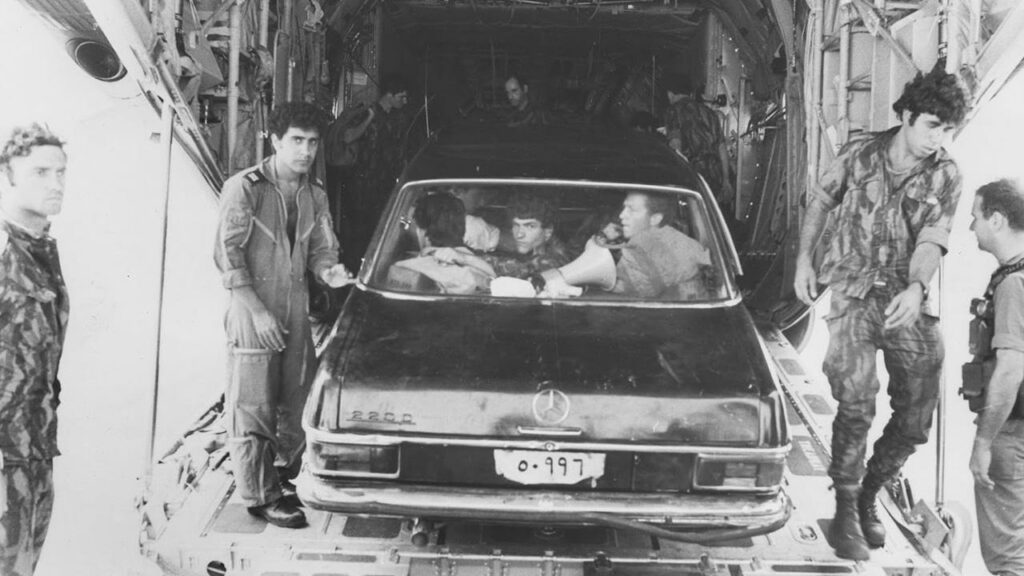

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef and the Halakhot of Hostages: Part II

When Israeli citizens were taken hostage in Entebbe in 1976, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef was asked if hostages could be exchanged for terrorists. What can his towering responsum teach us about the current moment?

Jewish Destiny in a Cheek Swab

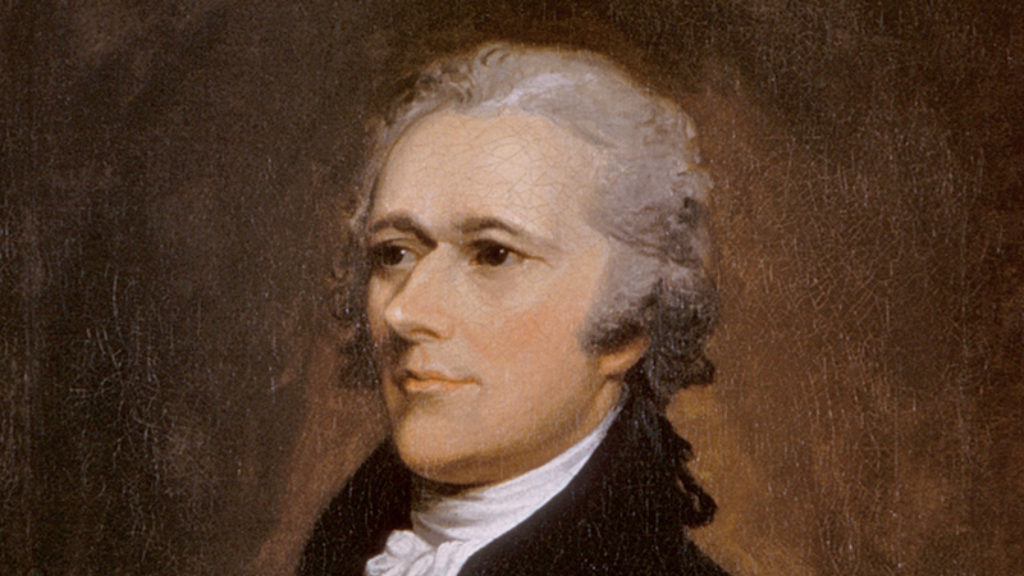

Possible Jewish ancestry has fascinated both Jews and non-Jews when it comes to American historical figures, reaching as far back as Alexander Hamilton.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In