No Tips

If the late Christopher Hitchens is to be believed, a portrait of Leon Trotsky graces the office wall of a reputedly conservative professor at the University of Chicago who once served as a member of the State Department Policy Planning Staff under Alexander M. Haig, Jr. Yet perhaps there is little to be surprised at here. Was there not more than a whiff of “internationalism” in the democratization programs pushed by the administration of George W. Bush? But to have spawned such followers is hardly a recipe for popularity, at least among the youth. Trotsky is little known and not much studied on American campuses these days.

Of course, the collapse of the Soviet Union also weighs against Trotsky. Whether the USSR embodied or betrayed the essence of communism, or perhaps did something in between, no one is much interested in shouldering responsibility for that monster. Thus Trotsky’s goateed visage no longer looks down on us from the red banners carried aloft at anti-war demonstrations, its place now taken by that of Che Guevara, a man who never accomplished or established anything at all. From the perspective of popular acclaim, better to be an empty military coat that we can fill with our own hopes and desires (replicas now available from Belstaff at $635 a pop) than a figure of historical importance weighed down by less fashionable baggage.

Joshua Rubenstein thinks Trotsky still “haunts our historical memory,” which is no doubt true for an older generation. In Leon Trotsky: A Revolutionary’s Life, he approaches his subject without the partisanship, pro or con, of earlier biographers, admiring Trotsky for his courageous struggle against Stalinism, but always mindful of his contribution to making Stalinism possible and perhaps even inevitable. This tension or contradiction between his ability to inspire himself and others to struggle against political oppression and his role in creating one of the most oppressive tyrannies the world has ever known is the theme that animates the book, and makes of Trotsky, in Rubenstein’s view, a tragic hero. The book is part of Yale’s Jewish Lives Series, so Rubenstein also considers the extent to which Trotsky’s being a Jew shaped or influenced him and therefore contributed to his fate.

This task poses a difficulty. For in Rubenstein’s account the open atheism of Trotsky’s father and the religious indifference of his mother did not allow him to develop “an emotional, let alone a spiritual or religious, attachment to being a Jew.” Trotsky himself denied that the special suffering of Russian Jews had anything to do with his hatred of the tsarist regime. When in power he denied help to Jews who petitioned for assistance by angrily telling them, “I am not a Jew. I am a Marxist Internationalist . . . I have nothing in common with Jewish things and I want to know nothing about Jewish things.” Perhaps more telling, since it occurred when he was living as an exile and before he became a prominent public figure, Trotsky complied with regulations in Vienna that children in the public schools receive instruction in the faith of their parents by designating his sons as Lutherans, something he thought would be “easier on the children’s shoulders as well as their souls.” In his Mexican passport, issued in 1937, next to religion he wrote the word “nothing.”

While Trotsky denied that being a Jew was of any importance to him, he did not altogether deny its importance. For instance, he turned down the position of Commissar of Home Affairs in the wake of the October Revolution so as not to give the Bolsheviks’ opponents an easy target: “Was it worthwhile to put into our enemies’ hands such an additional weapon as my Jewish origins?” Yet Rubenstein detects another almost subconscious level at which Trotsky maintained if not a genuine ahavat yisrael, then at least an affinity with Jews. He thus makes much of the fact that when living in the Bronx Trotsky frequented the Triangle Dairy Restaurant where most of the waiters were Russian Jewish immigrants, even though this required him to brave their mocking of his nasal intonations. As Rubenstein also notes, Trotsky worried that the high number of Jews in the Cheka, the Soviet Union’s first state security agency, might provoke even greater hatred of them as a group, although this concern seems to have arisen out of concern for the institution rather than for the Jews.

The deepest level at which Rubenstein thinks Trotsky lived a Jewish life was in his wholehearted embrace of revolutionary politics, almost without regard to its ultimate end. For Jews who had lost the faith of their fathers, “the all encompassing belief in revolutionary socialism” provided a kind of replacement. Here Rubenstein follows his subject’s own analysis, if not the keen pleasure he felt, on seeing Jewish radicals in Romania who, as Trotsky wrote, “escaped from the spell of religious melodies and national superstition and transferred their hopes to the socialist international of labor.”

In Trotsky’s particular case, the abandonment of his Jewish identify was fully self-conscious. “But his rejection of his Jewish origin was itself a form of engagement. As he spurned one messianic religion, he adopted another utopian faith—one that was secular and far more dangerous.” For Rubenstein, Trotsky’s revulsion at oppression and exploitation, as well as his rejection of the instinct of acquisition and the petit-bourgeois outlook on life, have at bottom a religious impulse. He speculates, briefly, that Trotsky’s embrace of dictatorship stemmed from the corruption that comes from having tasted power. But he then concludes that the Bolsheviks’ insistence on a monopoly of power, which laid the foundation for ruthless, one-party rule, arose out of their “Marxist faith” itself. The tragedy of Trotsky’s life, which reflects the tragedy of Marxism, is that “his belief in class struggle had more in common with theological certainty, with the kind of faith that characterizes religious belief, than with a scrupulous regard for scientific or historical examination.” Reality is left behind for dreams that left unchecked become a nightmare.

There is much in Trotsky’s life that supports Rubenstein’s conclusion. If we return to that Bronx deli in January of 1917, we find Trotsky lecturing those Jewish waiters he apparently longed to be with on the indignity of working for tips, refusing to leave a tip himself, and, worse, haranguing other customers to follow his example. The longing was not reciprocated. Just ten months later he was back in Russia working to implement a “universal labor obligation” that looked to abolish not just tips but salaries. But even if one grants its religious character, is there anything specifically Jewish about this kind of idealism? Rubenstein’s descriptions of Trotsky’s “steadfast belief in the power of the word” and his unwavering preference for universal claims over parochial concerns would seem to have more in common with the Apostles than with the Prophets.

Trotsky proved to be more flexible than would be seemly for a man possessed by theological certainty. When universal compulsory labor was found to be unproductive, Trotsky sought to “militarize labor,” a scheme that both hearkened back to the penal military colonies of the tsars and served as a prototype for the gulags to come. But this too failed to meet its quotas. If not exactly mugged, Trotsky was at least sometimes constrained by the recalcitrance of matter, if not human nature. Or, as he wrote of his experiment from the vantage of 1936, “Reality came into conflict with the program of ‘military communism.'” And reality won. Moreover, Trotsky’s decision to compromise ideological purity and recruit large numbers of tsarist officers is what kept the Red Army (and the Revolution) from collapse. Even when arguing late in his life in defense of revolutionary terror, he did so in terms no man of faith could ever embrace.

A means can be justified only by its end. But the end in turn needs to be justified. From the Marxist point of view, which expresses the historical interest of the proletariat, the end is justified if it leads to increasing the power of man over nature and to the abolition of the power of man over man.

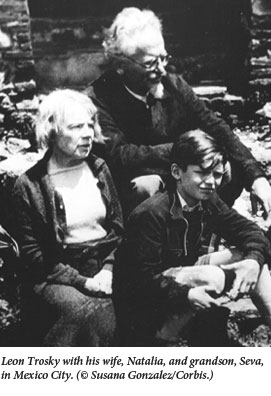

Trotsky the man might never have been able to bring himself to agree with latter-day Marxist Alexandre Kojève, who considered “Henry Ford to be the one great authentic Marxist of the 20th century,” but Trotsky the thinker might have been open to the possibility. On Rubenstein’s telling, Trotsky may even have acted on this view. When his grandson, Seva, came to live with him in Mexico at the age of 13 following the suicide of his mother and the death of his uncle, Trotsky forbade the entire household from speaking to him in Russian or discussing politics in his presence. He grew up to study chemistry, became a researcher in the pharmaceutical industry, married, and raised four daughters.

If, as Rubenstein also maintains, being a revolutionary means living a life not of “unquestioning allegiance” to some abstract ideal, but being able to pivot and “adopt positions he had once rejected,” then Trotsky’s solicitude for his grandson may well have been the most revolutionary and decent act of his life.

Suggested Reading

Lovers (and Haters) of Zion

A new history of Zionism tells the tale through the towering emotions of its proponents and adversaries.

Living Postcards

YIVO/Yeshiva University Museum's recent exhibit of pre-war home videos provides an extraordinary view into the lives of ordinary people.

Law, Lore, and Theory

In his new book, Chaim Saiman points out that this “exclusive focus on the precise details of religious practice” left the Pharisees, the forebears of rabbinic Judaism, open to Jesus’s critique that they mistook “the legal trees for the spiritual forest.”

Poland Is Not Ukraine: A Response to Konstanty Gebert’s “The Ukrainian Question”

Dovid Katz explores what it means to be a “good guy” and a “bad guy” in his response to Konstanty Gebert’s article on Ukraine and its Jews.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In