Not Just Hummus

Today’s cookbooks often tell us as much about who we are or who we would like to be as they do about what we eat. Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi’s new collection of recipes, reminiscences, and vignettes of Jerusalem’s food culture and Abbie Rosner’s culinary memoir of traditional foodways in the Galilee both give the reader food for the table and food for thought.

Co-written by a pair of internationally celebrated restaurateurs, Jerusalem: A Cookbook is at once a tribute to the flavors of its authors’ childhoods in the city and a celebration of its multicultural, syncretic, evolving food culture. Breaking Bread in the Galilee, by contrast, examines the ancient biblical roots of the region’s rural cuisines and their enduring manifestations. But both books describe food as a medium of memory, experience, and identity, while building on the authors’ own experiences of food as a bridge across the Jewish-Arab divide.

The four Ottolenghi bakery-cafés in London, of which Sami Tamimi is a partner and the head chef, have won acclaim for their creative take on cuisines from across the Mediterranean and Middle East and inspired two previous bestselling cookbooks. (The pair recently opened a full-fledged restaurant, NOPI.) Readers familiar with them will recognize in Jerusalem: A Cookbook the same signature combination of bold colors and zesty flavors. Ottolenghi and Tamimi’s book is full of exuberant recipes featuring intense combinations of spices, condiments, fresh herbs, and a wealth of vegetables, grains, and legumes.

Their culinary portrait of the city is presented largely through the prism of their own family histories. Both were born in Jerusalem shortly after its unification in 1967. Ottolenghi grew up in West Jerusalem as the son of an Italian-Jewish father and a mother born in Israel into a German-Jewish family, while Tamimi was born to Muslim parents in the Old City. Both also left the city in the 1990s, first for Tel Aviv and then for London, where they became close friends and business partners.

Neither Ottolenghi nor Tamimi has any interest in the so-called “purist” ideas of culinary authenticity, and their unorthodox approach determines their selection of recipes. Some are updated renditions of traditional dishes, while others are more loosely inspired by the flavors of Jerusalem as these interact to create “culinary combinations that belong to specific groups but also belong to everybody else.” Such recipes, Ottolenghi and Tamimi say, are aimed at “distilling the spirit of the place” rather than representing it. The result reflects the North African, Western European, Central Asian, and Sephardic influences brought to the city by its Jewish residents alongside the influence of the city’s Muslim, Christian, and Armenian communities. (The familiar tastes of Ashkenaz are occasionally present but fleeting.)

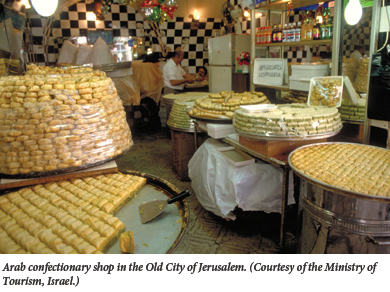

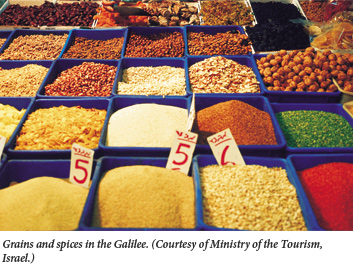

Ottolenghi and Tamimi understand that their nostalgic evocation of the aromas and flavors of their Jerusalem childhood is, like Proust’s famous madeleine, an act of imagination and longing. But their madeleine is just about as far as you can get from the subtle flavor of a spongy biscuit dipped into a lime infusion. Jerusalem: A Cookbook celebrates an explosion of jolting, sometimes overwhelming sensations: market stalls piled high with mounds of dark purple eggplants, blood-red tomatoes and pomegranates, and freshly baked flatbreads; pyramids of pungent, earthy za’atar (a spice mixture dominated by wild oregano) and tangy, dark crimson sumac; the din produced by the calls of venders enticing customers with warm, crispy falafel balls, a seemingly endless variety of flaky sweet and savory pastries, and, in the winter months, cups of warm sahleb (a mixture of milk and ground orchid root) garnished with ground ginger, cinnamon, and walnuts. Their Jerusalem is one where “food cultures are mashed and fused together in a way that is impossible to unravel. They interact all the time and influence each other constantly, so nothing is pure any more. In fact, nothing ever was.”

Simple, straightforward recipes from their childhood homes, such as the fattoush (a fresh vegetable salad garnished with dry pita bread) prepared by Tamimi’s mother or the meatballs served by Ottolenghi’s Italian-Jewish grandmother appear alongside imaginative fusion dishes such as eggplant stuffed with bulgur wheat (a staple of local Arab cooking) seasoned with chermoula (a piquant North African paste dominated by cumin, coriander, paprika, and preserved lemons); or watercress and chickpea soup inflected with ras el hanout (another North African spice blend) and infused with rose water. A Tunisian-Jewish fish soup is reinterpreted through the addition of seafood and fennel, and tomato gazpacho with endive includes calamari heads. (The laws of kashrut are of little interest to our authors.)

Simple, straightforward recipes from their childhood homes, such as the fattoush (a fresh vegetable salad garnished with dry pita bread) prepared by Tamimi’s mother or the meatballs served by Ottolenghi’s Italian-Jewish grandmother appear alongside imaginative fusion dishes such as eggplant stuffed with bulgur wheat (a staple of local Arab cooking) seasoned with chermoula (a piquant North African paste dominated by cumin, coriander, paprika, and preserved lemons); or watercress and chickpea soup inflected with ras el hanout (another North African spice blend) and infused with rose water. A Tunisian-Jewish fish soup is reinterpreted through the addition of seafood and fennel, and tomato gazpacho with endive includes calamari heads. (The laws of kashrut are of little interest to our authors.)

Ottolenghi and Tamimi have been in London for a long time, but they are on to something. Their book comes out at a moment when Jerusalem is undergoing a food renaissance of sorts, as its traditional ethnic cuisines are bolstered by a new surge of culinary creativity defined by bold combinations of Mediterranean and local influences, haute cuisine and street food, that have much in common with those celebrated in their recipes. Over the past few years, restaurants such as the trendy Machneyuda, situated on the outskirts of West Jerusalem’s increasingly gentrified open market, have been turning out dishes such as fish tartar on eggplant carpaccio, or “upside-down baklava” with tahini ice cream, that would fit well in the pages of this cookbook. (Ottolenghi and Tamimi’s recipe for braised eggs with lamb, tahini, and sumac is, in fact, directly inspired by one of Machneyuda’s signature dishes.) Like the new generation of Jerusalem foodies, Ottolenghi and Tamimi offer us a vision of what the city’s cuisine could become. The question they are interested in, as their mouthwatering selections reveal, is not so much the pedigree of Jerusalem’s foods as their future.

Abbie Rosner’s Breaking Bread in the Galilee: A Culinary Journey into the Promised Land, by contrast, is in many ways an elegy for a rapidly disappearing culinary world. Rosner, who grew up in Washington, D.C., moved to Israel in the late 1980s and settled in a small farming village in the Lower Galilee. Unlike the kaleidoscopic image of a multi-cultural urban food scene provided in Jerusalem by two native-born writers who left the city long ago, Rosner’s story is that of a recently arrived outsider moved to discover the human and culinary landscape of her new home.

Struck by the persistence of ancient agricultural and culinary traditions, Rosner began walking the landscape with a copy of the Bible, looking up every passage that described food and agricultural produce. Her wide-eyed wonder at her findings recalls, to some extent, the 19th-century literature of European travelers who equated their encounter with rural Arab life in the Holy Land with a journey back in time to an ancient world of biblical folkways and life habits. Yet what is ultimately compelling about the book is her first-hand description of these practices as they are revealed through the bonds she forges over time with individuals in the Galilee’s various ethnic communities: Bedouin farmers, Druze villagers, and urban Muslims and Christians. Her account of food as a means of overcoming suspicion and hostility and developing intimate human relationships across a seemingly insurmountable divide is, in the end, truly moving.

Rosner takes us across fields of wheat and barley strewn with the vestiges of ancient oil presses, through footpaths lined with wild fennel, asparagus, chicory, dark-green mallow leaves, and other edible plants that lend the traditional cuisine of the Galilee much of its character. She meets villagers who still grow and process their own fruits, vegetables, and wheat. Cherished collections of heirloom seeds are also passed on and cultivated on these small family farms from one generation to the next.

Rosner takes us across fields of wheat and barley strewn with the vestiges of ancient oil presses, through footpaths lined with wild fennel, asparagus, chicory, dark-green mallow leaves, and other edible plants that lend the traditional cuisine of the Galilee much of its character. She meets villagers who still grow and process their own fruits, vegetables, and wheat. Cherished collections of heirloom seeds are also passed on and cultivated on these small family farms from one generation to the next.

Much of the food Rosner describes is simple fare, and the few recipes she provides are even simpler. One reason for this is that the methods for preparing many of the foods she encounters are often too complex and time-consuming for most of her readers to reproduce. Many require painstaking labor and traditional tools, taking hours, if not days, to make. Readers would not be well advised, for instance to try their hands at sautéed luf, even if it were available to them. It is a dark, leafy plant cooked with olive oil and onion, whose potent toxin must be neutralized in the cooking process. (Rosner learns this the hard way.) It would be almost as hard to attempt her simple recipe for ellet (wild chicory) salad. One small onion, two tablespoons of ground sumac, olive oil, lemon juice, and salt tossed together in a bowl are easy enough, but who has a field of chicory within walking distance of the kitchen?

Rosner’s book is neither an academic study nor a collection of recipes; it is something more rare: a glimpse of a disappearing food culture that is overlooked by mainstream Israeli society, including the Machane Yehuda chefs and foodies, and virtually unknown to non-Israelis. (Rosner ended up self-publishing her book when she was unable to interest a commercial publisher, and one does occasionally wish that she had been able to work with a skilled editor.)

Rosner’s attempts to communicate across linguistic and cultural boundaries culminate in her encounter with Balkees, a feisty forty-something resident of Nazareth. Born in a nearby Muslim village and married at a young age, she is a an outstanding self-taught cook and baker of highly prized traditional pastries, and a purist who goes to great lengths to source her own ingredients directly from their growers and purveyors. And while Balkees is perfectly happy to create her own “fusion” interpretations of unfamiliar foods (she touches up the bagels baked by Rosner’s husband with her own spice mix and serves them with homemade goat cheese), she balks at the idea of anyone tampering with her own traditional recipes. One can only imagine her reaction to the shortcuts recommended by Ottolenghi and Tamimi to accommodate busy global urbanites, not to speak of their liberal use of spices in dishes featuring traditional ingredients such as freekeh (roasted green wheat kernels), whose ethereal, smoky taste she refuses to compromise with even a single fried onion.

These explorations of unique enclaves within Israel’s contemporary culinary landscape by writers who occupy the double position of both insiders and outsiders help to map the coordinates of Israel’s contemporary food culture as a whole. On the one hand, it attempts to define itself by embracing the kind of syncretic, multicultural influences celebrated by Ottolenghi and Tamimi; on the other, it is searching for an “authentic” cuisine rooted in a local terroir and a deep connection to the land and its produce. This has become associated, in the collective Israeli imagination, with the culinary culture of the country’s Arabs and with the world of biblical foodways studied in Rosner’s book.

Over the past two decades, this cuisine-in-the-making has been actively reinvented by prominent local chefs such as Haim Cohen, Erez Komorovsky, Eyal Shani, and Ezra Kedem. Together with a younger generation of culinary impresarios, these chefs have drawn from a shared inventory of sources ranging from the ethnic traditions of their own families to more general Mediterranean and Middle Eastern sources of inspiration and French and Italian influences and techniques. They have also embraced the use of fresh, seasonal ingredients, products provided by the recent explosion of new boutique wineries, olive oil and cheese producers, and small-scale farms, as well as—at least in theory—the use of indigenous wild plants and heirloom varietals. This is one reason that the traditional Ashkenazic cuisine of Eastern and Central Europe has tended to fall by the wayside.

Although these developments reflect international culinary trends, they also have a culturally specific resonance that has to do with a sense of place at once real and imagined. In the early years of Israeli independence, the idea of using “local” ingredients meant teaching housewives (many of them new immigrants) how to cook with the produce of the country’s new industrial agricultural system and to overcome the challenges posed by the scarcity of quality ingredients. There was no longing for the madeleines or matzah balls of the Jewish diaspora in this era’s cookbooks. Instead, they produced a melting-pot vision of Israeli food that privileged frugality, nutrition, and hygiene over the pleasures of the table.

Lilian Cornfeld, an immigrant from Canada and Israel’s most important cookbook writer of that era, provided her readers with hundreds of recipes describing how to whip up a variety of meals out of inexpensive, widely available ingredients. Created to represent a new national culinary identity, “Israeli salad” or “Israeli cauliflower” (fry florets in a batter and cook until soft in water seasoned with salt, sugar, tomato juice, or lemon) starred on Cornfeld’s menus alongside zucchini spears boiled to resemble asparagus and a recipe in which lamb—now celebrated as one of those quintessentially “local” foodstuffs—is used to create mock goose! (“Debone a leg of lamb, fill cavity with bread stuffing, sew to resemble goose, dust with flour, and fry to brown.”) The idea of cooking with wild greens, meanwhile, was associated, above all, with the hardships endured during the 1948 siege of Jerusalem, when city residents were forced to forage for food near their homes.

During these early years, when fine restaurant dining was virtually non-existent in Israel, popular eateries serving hummus, falafel, roasted meat skewers, and assorted salads came to represent, for most Israelis, the embodiment of Arab cuisine. To this day, as Rosner puts it, “the average Jewish Israeli’s experience of Arab food is limited to the formulaic fare of Middle Eastern restaurants, which presents about as faithful a reflection of its origins as that of American Chinese restaurants.” Paradoxically, in a hegemonic Ashkenazic culture, this pseudo Middle-Eastern cuisine became “authentic” local, Israeli food.

During these early years, when fine restaurant dining was virtually non-existent in Israel, popular eateries serving hummus, falafel, roasted meat skewers, and assorted salads came to represent, for most Israelis, the embodiment of Arab cuisine. To this day, as Rosner puts it, “the average Jewish Israeli’s experience of Arab food is limited to the formulaic fare of Middle Eastern restaurants, which presents about as faithful a reflection of its origins as that of American Chinese restaurants.” Paradoxically, in a hegemonic Ashkenazic culture, this pseudo Middle-Eastern cuisine became “authentic” local, Israeli food.

It was not until the 1980s, as Israelis began regularly traveling abroad, that cookbooks took to introducing international cuisines and celebrating the values of good food. In the 1990s, an explosion of new cookbooks began to feature the ethnic cooking of different immigrant groups in Israel (previously relegated by cookbook writers such as Cornfeld to the vague and all-inclusive category of “Mizrachi,” or “Oriental” cooking), while also beginning to reflect the formation of a New Israeli cuisine.

Interestingly, two new Hebrew-language books, released at more or less the same time as Jerusalem: A Cookbook, are similarly devoted to culinary portraits of the country’s two other major cities, Haifa and Tel Aviv. Food writer Hila Alpert’s culinary portrait of Haifa, Yesh Makom Ba-Ir Hatachtit (There’s a Place Downtown) is devoted to the city’s downtown eateries, bars, and food shops, while veteran journalist Nathan Dunevich’s Mi-kiosk Gazoz ad Misedet Shef-Mea Shnot Ochel be-Tel Aviv (From a Soda Kiosk to a Chef’s Restaurant—100 Years of Food in Tel Aviv) covers a century of eating in Tel Aviv.

One of the first chapters in Dunevich’s book is devoted to the area surrounding the Levinsky Market on the city’s southern edge. During its heyday in the 1920s and 1930s, the produce stalls were surrounded by shops and drinking holes largely owned and frequented by new immigrants from Turkey, Greece, and Bulgaria. The market, which was closed down in the 1940s, was reborn several decades later on a stretch of the same street lined with stores specializing in spices and dried fruit and nuts, as well as specialty shops selling Greek and Turkish cheeses, olives, pastries, anise-flavored drinks, and homemade condiments, where snatches of Ladino were still heard regularly until not long ago.

Today this market area, a short walking distance from my own apartment in Tel Aviv, is undergoing a sudden revival, which might be described as a peculiar form of culinary arbitrage. While many of the neighborhood’s long-standing food establishments are closing down, they seem to be almost simultaneously reappearing as reinvented or reinterpreted versions of their old selves. The dark-walled eatery that until just a few months ago served up fresh, simple Balkan-style dishes to a loyal group of customers is gone, replaced by a light-filled café whose food the young owners describe as inspired by Greek mezze, chalking up their concept to a recent trip to Athens. And while the doors of the bakery down the block, which first opened in the late 1930s and specialized in the traditional almond pastries of Thessaloniki Jews, are now shuttered, the owners of new restaurants and cafés around the corner are serving products sourced from some of the surviving old neighborhood stores alongside their own homemade pasta and home-cured olives.

Condensed into the space of a few city blocks, this little culinary laboratory seeks, like Ottolenghi and Tamimi in Jerusalem: A Cookbook, neither to erase nor to reproduce its own past. Rather it glories in the possibilities that the exchange between past and present serve up.

Suggested Reading

Journeys Without End

For some three decades Lionel and Diana Trilling shared a limelight that was not quite identical but never entirely separate.

Jokes and Justice

We were sitting in our apartment one evening when a Spanish philosopher dropped in ...

Why There Is No Jewish Narnia

So why don’t Jews write more fantasy literature? And a different, deeper but related question: why are there no works of modern fantasy that are profoundly Jewish in the way that, say, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is Christian?

Manufacturing Falsehoods

An immense echo-chamber has been built, and the line is always the same: Israel is not allowed to be a country like any other.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In