Manufacturing Falsehoods

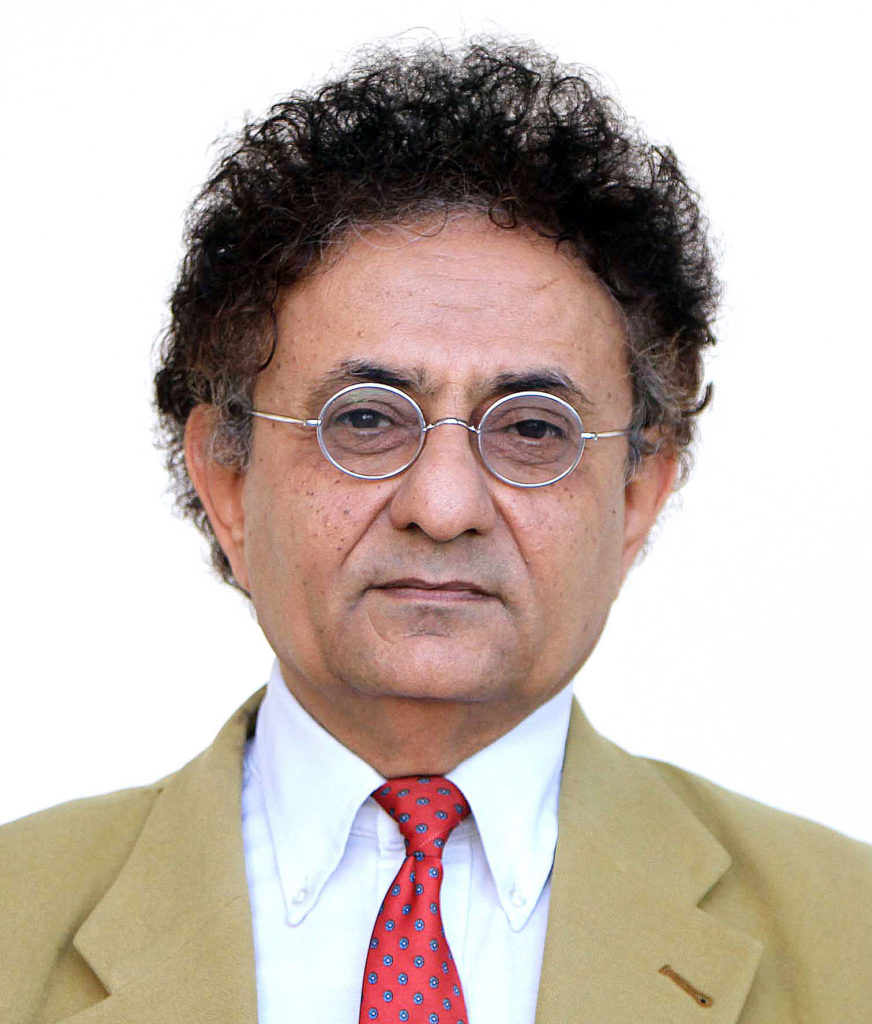

Ben-Dror Yemini has devoted a lot of his time as a journalist, first for Maariv and now for Yedioth Ahronoth, to refuting what he regards as false allegations against the Jewish state made by NGOs, academics, and the media. In 2014 he summed up his widely ramified defense of his country in a book entitled Industry of Lies, which the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy has now published in an English translation. It is a book that combines the passionate advocacy of the opinion pages with considerable research. Although it does not cover the last four years, it remains an important resource for those who wish to combat, or merely understand, the calumnies aimed at Israel.

Yemini spends little time explaining Zionism or justifying the creation of the state of Israel or glorifying any of the state’s deeds. Nor does he proclaim Israel to be free of guilt. He aims not to overstate or accentuate the positive but to eliminate the negative view of Israel, to the very great extent that it is inaccurate, unfair, and divorced from any notion of what goes on in the real world of states and politics.

Yemini places a lot of blame for the vilification of Israel on journalists. But writers for newspapers—Israeli and foreign—are by no means his only concern. “Every journalist,” he writes in his preface, “points to two historians, every historian points to two politicians, and every politician points back to two journalists. An immense echo-chamber has been built, and the line is always the same: Israel is not allowed to be a country like any other, not an ordinary country like the United States or France that sometimes commits crimes or even atrocities but is basically to be judged on a reasonable and proportional human scale. Instead, it is evil at its core, born in sin, and must be fought and destroyed, rather than engaged in a reasonable fashion.”

Israel is not allowed to be a country like any other . . . Instead, it is evil at its core, born in sin, and must be fought and destroyed, rather than engaged in a reasonable fashion.

More specifically, what are the lies? In brief, Israel’s enemies have represented it as a diabolically cruel state, solely responsible for the expulsion of the large majority of the Palestinians from their native land and the fierce oppression of those who have remained there under Israeli control. They claim that it continues to subject the Arabs who are its citizens as well as the others who have since 1967 lived under its administration to a system of governance that is tantamount to apartheid, and even engages in genocide.

According to Yemini, if the Palestinians suffered a tragic defeat in 1948, it was their own fault. Already in the 1930s the Palestinians refused to accept a partition of the land, and one mustn’t forget Hajj Amin al-Husseini’s wartime and postwar threats to annihilate the Jews, or the Arab League’s determination to expel all Jews from the Arab states in the aftermath of Israeli independence. “The [Palestinian] refugee problem,” Yemini writes, “would not have been created without the sweeping Arab rejection of the Partition Plan in 1947” and would not have worsened even further had the Arab states not invaded Israel in 1948. This particular refugee issue, Yemini argues, cannot be evaluated in isolation, but needs to be considered in the context of other ethnic conflicts of the mid-20th century that were interconnected with the redrawing of borders, such as those in the Balkans, the treatment of the ethnic Germans of Eastern Europe after World War II, and the struggle between Hindus and Muslims in India and Pakistan. The departure of 700,000 or so Palestinian refugees in the course of the 1948 war was a relatively smaller migration and resulted in fewer deaths than the displacements resulting from these other situations, yet it has received far more attention than any of them. “The crux of the problem is that many of those who teach in Middle East study programs and other relevant academic departments completely ignore these fundamental facts.”

What about the Arabs who stayed in Israel and who, together with their descendants, now number close to two million and constitute a fifth of the country’s population? Yemini readily acknowledges that in their case, “[t]here are problems. There is discrimination. There are prejudices.” But he documents the vast improvement in the life of Israeli Arabs over the years, questions whether prejudice and discrimination constitute the primary cause of the problems that still exist, and effectively refutes the notion that the Arab citizens of Israel are the victims of anything like apartheid. It is very revealing, according to Yemini, that “Israeli Christians, who are also Arabs, are on a par with—and sometimes even surpass—Jewish Israelis in socioeconomic terms, in contrast to Arab Muslims, who remain less well off.” The fact that only 13% of Muslim women in Israel participate in the workforce, as opposed to 42% of Christian women, may explain this disparity better than anything else. Life expectancy and literacy levels are higher among Israeli Arabs than they are among the populations of any of Israel’s neighbors, and the gaps in these areas between Israeli Arabs and Israeli Jews have greatly narrowed over the last half-century.

How, in any case, can one speak of apartheid in a country whose president, in 2011, was sentenced to seven years in prison by a panel of judges headed by an Arab justice or where, notes Yemini, the chief administrator of Rambam Medical Center in Haifa is also an Arab? In a survey conducted by the Israel Democracy Institute in 2014, 65% of them described themselves as “proud to be Israeli.” Similarly, in a 2014 poll conducted by Israel’s Channel 10, 77% of the Arab respondents preferred living in Israel to being governed by the Palestinian Authority. Indeed, “a majority of Israeli Arabs know that with all its problems, their day-to-day life is better than anywhere else in the Middle East.”

Several of the book’s most important chapters present statistics pertaining to the improvement of the standard of living among Palestinians on the West Bank and Gaza since 1967. According to United Nations figures, life expectancy at birth among Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza increased from 48 in 1967 to 72 in 2000, “higher than in most Arab countries.” Infant mortality declined from between 152 and 162 per 1,000 births in 1967, to between 53 and 63 by 1985. In 1967, there were no universities in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Today there are 10 along with 20 community colleges. Improvements in access to running water through modern supply systems increased per capital water consumption. Hence “the notion that Israel is committing genocide—be it slow or fast, direct or indirect—is clearly complete nonsense.” Far from undermining higher education in the West Bank, Israel’s support of the establishment of new universities helped to create several generations of highly literate, educated Palestinians, some of whom ironically became activists in BDS initiatives.

The notion that Israel is committing genocide—be it slow or fast, direct or indirect—is clearly complete nonsense.

Yemini refers to several critics who describe some of Israel’s policies as forms of genocide and notes the deleterious impact of their accusations. He notes that in 2012, for instance, a study ordered by the German Bundestag found that 41% of Germans thought that “Israel is waging a war of annihilation against the Palestinians.” Yemini then adds up the numbers of Muslims—overwhelmingly innocent civilians—killed in wars or slaughters, or who died of starvation and disease due to war since the 1960s in Algeria, Sudan, Biafra, Afghanistan, Somalia, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen, Chechnya, Syria, Jordan, Chad, Kosovo, Zanzibar, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Pakistan. The result is a total of around eight million people. Yemini estimates that since 1948 the Israeli-Arab conflict, in contrast, has caused between 80,000 and 120,000 deaths on the Arab side, a toll that includes the major wars of 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973 and the more recent wars in Lebanon and Gaza. He also reports that according to B’Tselem, a left-leaning organization in Israel that regularly criticizes the Israeli military, 11,500 Palestinians have died in the past 30 years in conflict with Israel. Yemini has his doubts about the accuracy of this figure, but even if it is correct it amounts to “less than the number of Muslims killed in one year by former Syrian dictator Hafez al-Assad in 1982”—to say nothing of the far greater number killed by his son in recent years.

Yemini’s chapters on reporting on the Gaza wars of 2008–9, 2012, and 2014 go over the now familiar exaggerated or simply false claims about civilian deaths first made by Hamas and then repeated in the press, claims that were given legitimacy for a while by the Goldstone Report. He recalls the details of what turned out to be a fabricated story of the killing of Muhammed al-Dura, a young Palestinian in Gaza, and the refusal of the French journalists involved to acknowledge their role in fostering the false accusation leveled at the Israeli army. Yemini recounts the efforts of the Israeli Defense Forces to warn civilians living in buildings held by Hamas soldiers of impending attacks, and compares civilian deaths caused by the IDF to the much higher figures associated with the military interventions of the United States, Russia, and NATO armies. “Only the Israeli army, which does more than any other army to protect civilian lives during combat, serves as the regular punching bag of world public opinion.”

Israel’s adversaries apply similar double standards to Israel’s diplomacy. Despite Israeli agreement and Palestinian rejection of the partition plan of 1947, the Clinton Plan of 2000, and the Ehud Olmert Plan of 2008, among others, a “huge network, with impressive logistical capabilities” blames Israel for continuation of the conflict, supports BDS efforts, and serves as “the spearhead of the industry of lies.”

Like many Israelis from the center-left to the extreme right, Yemini is furious with the editors and writers of Haaretz:

In the last decade, Haaretz, the most widely read Israeli daily newspaper in English, has become a central pillar for the industry of lies. The problem is not the opinion pieces. The problem lies in the biases, distortions, and falsehoods, as well as in the encouragement of Palestinian intransigence and violence that Haaretz supports.

While parts of paper remain serious, “unfortunately, the core of writing on the conflict” in recent years has been “dominated by people on the outer margins of the radical Left.”

“While they cloak themselves as progressive and democratic,” Yemini writes, “Haaretz seeks to ‘detour around’ Israelis’ decision-making machinery (in essence, to cancel-out self-determination by the body public and its elected leaders) by selling movers and shakers abroad (both opinion-makers and policy-makers and world public opinion) a bill of goods with three messages about Israel, that need refutation: (1) that Israel commits war crimes (2) that Israel is an apartheid state (3) that Israel refuses to make peace, not the Palestinians.”

Yemini’s examples of erroneous reports along these lines in Haaretz include Gideon Levy’s report of Israeli border patrol soldiers tying prisoners to donkeys that are then sent running until the victims die of wounds and Yitzak Laor’s claim that Israeli soldiers blew up a mosque “with hundreds of people inside, including children.” Yemini also cites Levy’s claim in 2012 that a survey showed that most Israelis supported an apartheid regime and his favorable articles about Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, after the latter made widely-reported anti-Semitic comments. Then there is Amira Hass’s 2008 comment in the face of the Palestinian intifada that “[t]hrowing stones is the birthright and duty of anyone subject to foreign rule.” Fourteen Israelis had been killed by rocks. Yemini cites Levy’s claim in an interview with the British paper, the Independent, that during Operation Cast Lead in 2008-09, a picture of a dog appeared on front page of “the most popular newspaper in Israel” but nothing was there about the “tens of Palestinians killed” that day. None of the authors were fired or disciplined. He adds that Haaretz “no longer represents the liberal or left-wing of the Israeli public—wings that support both human rights and a Jewish and democratic state. There is a Left that rebuts lies and falsehoods about Israel, and there is a Left that disseminates them.” Yemini may exaggerate somewhat about Haaretz, but it doesn’t matter as much as it did when the book was written—not outside of Israel anyhow. For many years now, between the conservative Jerusalem Post and the centrist, increasingly comprehensive Times of Israel, not to speak of the explosion of social media, English readers have other sources.

Some readers may be put off by the strength of Yemini’s rhetoric, but the facts are on his side and, unfortunately, little has changed since he wrote his book. If anything, at least on American campuses, the false image of Israel as a uniquely malevolent state has gained even more ground over the last few years, and Yemini’s review of the evidence up through 2014 remains deeply instructive about how that has happened.

Suggested Reading

The Romance and Rage of Rashbi

In the technical halakhic sense, Lag BaOmer is not really a festival, and it is not attested to in any of the classical sources. So how did the Hilula de-Rashbi, as the Meron Lag BaOmer celebration is called, become such a large, and largely Hasidic, pilgrimage—and rave?

Israel’s Declaration of Independence: A Biography

Who wrote Israel's founding document and how does it express Israel’s values?

Could It Have Happened Here? The Implausible Plotting of The Plot Against America

Was America in 1940 primed for an antisemitic leader, as Roth and his adapters would have us believe?

There He Goes Again

Foer departs from Roth’s model in many ways; perhaps most unsettling is the fact that he confuses crassness for humor.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In