Poems Like Mountains

“I was a year old,” Rivka Miriam says, “and my father would hold me in his arms and throw me up and down and I laughed and laughed and laughed. Each time he threw me up he’d yell in Yiddish ‘Rivkela Rivkela where’s Savta?’ ‘Killed.’ ‘Rivkela Rivkela where’s Miriam?’ ‘Killed.’ ‘Rivkela Rivkela where’s Chaim?’ ‘Killed.’ He’d say all the names and I’d laugh and laugh. I was a year old, I feel I absorbed it from the start.”

Rivka Miriam’s disciplined, imagistic poems speak in the voice of this child. Born in Jerusalem in 1952 to the Yiddish writer Leib Rochman, Rivka Miriam is named for her grandmother and aunt, both of whom perished in Treblinka. Considered a yeled peleh or prodigy, she flourished in the salon-like atmosphere of her childhood home, and began to write poems about her ancestors, often sounding like a resurrected Holocaust victim. “I was not born. / I was restored to life,” reads an early poem.

My Yellow Dress, the poet’s first book, was published when she was 14 and earned her the never-quite-escapable label of “Holocaust poet.” These Mountains, translated with aesthetic alertness by Linda Stern Zisquit, shows us how insufficient and misleading that label is. There are no boxcars or bars of soap in these poems; almost nothing on the referential level points to the experiences of her parents and grandparents. It is reverence for life, not reference to death, that Rivka Miriam achieves. The simple structure and even tone of these poems stands in sharp contrast to the histrionics of most “Holocaust poetry.” (Charles Reznikoff’s Holocaust is an important exception, which, significantly, was drawn from testimony offered during the trials of Nazi criminals.) In her two most recent books, Miriam does write about her murdered relatives: her pregnant aunt, her uncle, her great-uncle (“who ran wrapped in a tallit and yelled ‘Redemption!’”). Reading these harrowing poems makes one realize how oblique the rest of the poems are.

One would not expect it, but the tone of these poems is playful rather than ponderous. Perhaps like her father converting the names of the dead into a game, Rivka Miriam turns the darkness into poetry. This is not to say that she becomes acclimated to horror, as is the traditional argument in English poetry. “We grow accustomed to the Dark,” wrote Emily Dickinson. In Paradise Lost, Milton put the same argument in the demon Belial’s mouth: “This horror will grow milde, this darkness light.” Miriam strongly argues against any such acclimation. “We didn’t get used to dying,” she writes:

though our death, like an old husband

lies close to us and his arm, as if asleep

carelessly hugs the thickness of our hip

Death and terror are domesticated but not integrated.

The Biblical allusions for which she is known are not so much allusions as they are a familiar and meaningful context. There’s no appeal to God in the poems, and she situates herself in the Bible’s stories—not the awe and terror of the Prophets, or the keening of the Kinot. Like a child, she attends to the familiar parts of Scripture: Miriam’s well, the Jonah narrative, Moses, Lot’s wife. This is not to say that her knowledge is limited—quite the opposite. Zisquit helpfully observes that Rivka Miriam “presents a self tapping into the unconscious, a sort of faux naïf attempting to stay a little girl, and she sustains that persona—neither clever nor sophisticated—as part of a technique to maintain a natural fresh innocence, a sense of wonder in her work.”

The poems are short: rarely longer than half a page, with few stanza breaks, as if the poet is reluctant to enter and exit the silence. Poetic devices are almost completely absent from the work. Not only is there no rhyme (Israeli poets dropped rhyme sooner and more decisively than their English counterparts), but there is very little assonance or consonance, and lines are rarely broken “artistically” mid-phrase. The one poetic device of which she makes heavy use is repetition, and like her father’s “Rivkela Rivkela” game, it’s more often used to evoke absence than to underscore presence: “My fathers are all dead, / my fathers are dead. / All of them.” Of course, the absence of poetic devices doesn’t indicate the absence of poetry. Rivka Miriam eschews these devices, strips language almost bare, and it still sings.

It is not just language that gets stripped down. The poems are peopled with the infertile and disabled. Playing with Exodus 13:8 on teaching one’s child about the departure from Egypt, she instructs: “And you shall teach your son muteness / that very day.” Circumcision, too, becomes a disability:

A handsome circumcised man grabs my

shoulders,

he’s feeling what’s left of my wings.

—Both of us are remnants—I tell him—

I and my wings, you and your organ.

The Hebrew word “remnant” (sarid) also means “survivor.” It is typical of Rivka Miriam to use words like these, that can be contextualized and re-contextualized, sometimes seeming to be embedded in a post-Holocaust narrative, sometimes not.

Another theme of the poems is that of birth and procreation. Interestingly, these images are often tied to men. “God closed his womb,” she writes. In a poem on the binding of Isaac, “Abraham was binding his son / as with umbilical cords / to return him to his old, brittle loins.” One of her best-known poems, “That Very Night,” says:

Now that it is clear that I’m a man

it turns out that I’m the father of my children

and their growth was in a father’s womb

warm and hairy and tearless.

In contrast, women in Rivka Miriam’s work are often barren, like the biblical matriarchs, “stone mothers” who cannot give birth or nurse.

Rivka Miriam is well-known and celebrated in Israel, where she has written twelve books of poetry as well as short stories and children’s books, but this is her English language debut. The translations are presented opposite the Hebrew, though it should be said that because of the poet’s simple syntax and vocabulary, a beginning student of the language could tackle many in the original. The English text is slightly pocked with some rather unfortunate typographical errors (“I will prostate myself”). Paradoxically, the potency of the poems is somehow lessened when they are read as a collection, like music sustained at too high a pitch for too long. But read individually, the poems are searing.

Suggested Reading

Kibitzing in God’s Country

It may come as a surprise that there is an entirely different Catskills, a Catskills that doesn't involve Grossinger's, bungalow colonies, or Jews, in the words of Billy Crystal, eating "like Vikings."

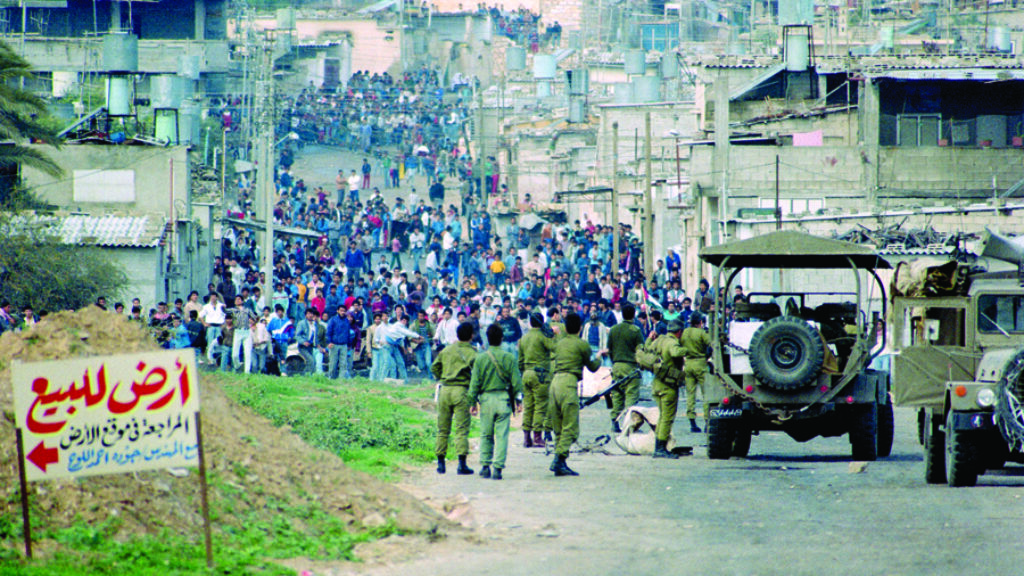

The Ethics of Protective Edge

How does one deal with Hamas, an enemy that has eliminated any trace of the distinction between combatants and non-combatants, except for the purposes of propaganda?

Pessimism Not Despair: A Reply to My Critics

"Just as the turmoil aroused by Israel’s new government has overlooked the Palestinian issue while concentrating on a more immediate crisis, so have the responses to my article."—Halkin writes back.

Sacrificial Speech

Just a few years after the publication of her Purity, Body, and Self in Early Rabbinic Literature, Mira Balberg has somehow managed to write another path-breaking work on another formidable and arcane section of rabbinic literature—sacrificial law.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In