Questioning in the Darkness

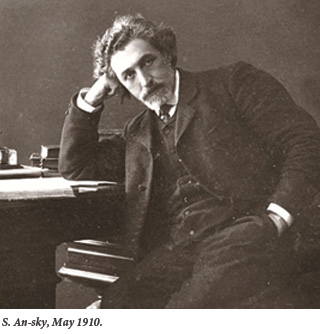

A century ago, on the eve of World War I, an itinerant writer, socialist revolutionary, and ethnographer named Shloyme-Zanvl Rappoport assembled thousands of questions for a survey directed at shtetl residents in the Russian Empire’s Pale of Settlement. Better known to the world today as S. An-sky, author of the play The Dybbuk, Rappoport aimed at nothing less than a complete record of rapidly vanishing Jewish folkways, from conception and birth through childhood, marriage, family, illness, death, and the afterlife. “The older generation, the precursor of the rupture in our civilization,” he wrote in 1909, “is dying out and taking with it to the grave the legacy of a thousand years of folk creativity.” An-sky was hardly the first to mine the pungent depths of contemporary Jewish folk culture for artistic purposes such as The Dybbuk, whose artful reworking of popular notions of predestination and the transmigration of souls would catapult the play to fame.  The Yiddish writer I. L. Peretz had appropriated Hasidic tales to create his late 19th-century neo-romantic fictions. An-sky’s fellow traveler on his 1912 ethnographic expedition, Yuly Engel, composed Jewish art music that echoed the melodies he had recorded, and most famously, Marc Chagall’s paintings combined folk motifs with modernist devices. Nor were Jews alone in their efforts to salvage folk customs from the ravages of industrialization. From the Brothers Grimm to Bela Bartok, countless writers, composers, and artists drew upon Europe’s waning peasant cultures to animate their creative work.

The Yiddish writer I. L. Peretz had appropriated Hasidic tales to create his late 19th-century neo-romantic fictions. An-sky’s fellow traveler on his 1912 ethnographic expedition, Yuly Engel, composed Jewish art music that echoed the melodies he had recorded, and most famously, Marc Chagall’s paintings combined folk motifs with modernist devices. Nor were Jews alone in their efforts to salvage folk customs from the ravages of industrialization. From the Brothers Grimm to Bela Bartok, countless writers, composers, and artists drew upon Europe’s waning peasant cultures to animate their creative work.

As Nathaniel Deutsch shows in The Jewish Dark Continent, however, An-sky’s ambition went far beyond rescuing Jewish folk traditions and transforming them into sources of artistic inspiration. The ethnographic expeditions were meant to capture what An-sky had come to revere as the authentic Oral Torah of his time—a living folk-culture—and thereby to supply the ingredients for a Jewish national renaissance. In this Oral Torah An-sky heard not the vox dei but the vox populi—the voice of a people, moreover, who of late “talked about themselves more, yet understood themselves less” than any other. In An-sky’s imagined future, not rabbis but ethnographers would perform the exalted task of preserving, transmitting, and interpreting the Jews’ deepest truths. As Deutsch suggests, it was An-sky’s dream that Russian Jews should become both subjects and objects of their own distinctive ethnography.

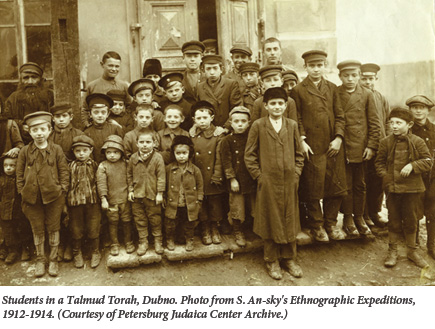

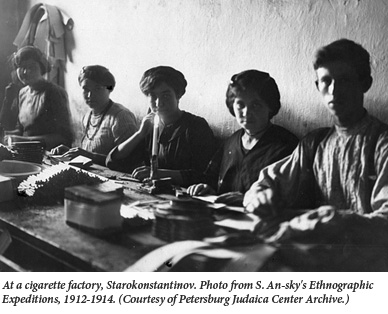

The actual results of An-sky’s expeditions conducted in the summers of 1912-1914, the last cut short by the guns of August, failed to meet his lofty ambitions. It had never been clear how, even under favorable circumstances, a magical folklore could serve as a foundation for modern Jewish existence, let alone in the context of rising scientific literacy, ethno-nationalisms, and class conflict. It was one thing to achieve a kind of re-enchantment in a play or short story, quite another to do so in real life. Yet the harvest of An-sky’s expeditions was impressive nonetheless: thousands of sepia-tone photographs of shtetl Jews, their houses of worship and burial sites; a trove of ritual objects and works of folk art; countless wax-cylinder recordings of folktales, legends, jokes, melodies, and songs; and hundreds of manuscripts, from marriage contracts to private letters. Together they comprise the richest record of everyday life in Jewish Eastern Europe ever collected. Had they not been locked up during seven decades of Soviet rule, we might have been spared the saccharine pieties of books like Life Is With People: The Culture of the Shtetl and plays like Fiddler on the Roof.

The Jewish Dark Continent is concerned not with An-sky’s ethnographic harvest, but with his ethnography itself. Two-thirds of the book consists of Deutsch’s fluent translation from the Yiddish of the 2,087 questions An-sky and his team intended to pose to their informants in dozens of shtetls across the Pale. Among other things, they asked: Are girls permitted to play with their brothers? At what age are school children no longer beaten? Do yeshivas have student newspapers? Is it easy to get authorization for soldiers to observe Jewish holidays and keep Jewish customs? Do people still make matches between children who are not yet born? Is there a custom that the parents should stand by the door outside the nuptial bedroom? To whom do people show the sheet in the morning, and how does this take place? Does it still happen that after the wedding the wife earns a living and the husband doesn’t do anything? By which signs do people begin to consider an old man to be senile? Is it considered a disgrace for children to give up their old parents to a home for the elderly? Is it considered a remedy to place a tied-up rooster under a sick person’s bed? Do people eat the fruit of trees that grow in cemeteries?

The Jewish Dark Continent is concerned not with An-sky’s ethnographic harvest, but with his ethnography itself. Two-thirds of the book consists of Deutsch’s fluent translation from the Yiddish of the 2,087 questions An-sky and his team intended to pose to their informants in dozens of shtetls across the Pale. Among other things, they asked: Are girls permitted to play with their brothers? At what age are school children no longer beaten? Do yeshivas have student newspapers? Is it easy to get authorization for soldiers to observe Jewish holidays and keep Jewish customs? Do people still make matches between children who are not yet born? Is there a custom that the parents should stand by the door outside the nuptial bedroom? To whom do people show the sheet in the morning, and how does this take place? Does it still happen that after the wedding the wife earns a living and the husband doesn’t do anything? By which signs do people begin to consider an old man to be senile? Is it considered a disgrace for children to give up their old parents to a home for the elderly? Is it considered a remedy to place a tied-up rooster under a sick person’s bed? Do people eat the fruit of trees that grow in cemeteries?

To An-sky’s elaborate questionnaire, originally published in 1914 as Dos yidishe etnografishe program, Deutsch has added over seven hundred annotations, as well as a lengthy introduction analyzing An-sky’s quest for a distinctly Jewish ethnography. Those who pause at the prospect of reading some two thousand questions may take comfort in knowing that the indefatigable An-sky originally intended the number to be closer to ten thousand. As he put it in another context, “I threw myself in all directions.”

“There is something profoundly Jewish,” Deutsch writes, “about a text consisting entirely of questions.” His introduction makes the case for the deeply Jewish character of An-sky’s project, likening the questionnaire to a Sefer Minhagim (Book of Customs), and the ethnographic collections, with their long period of dormancy behind the Iron Curtain, to a geniza. Like his protagonist, Deutsch seems eager “to legitimate the subject of Jewish ethnography within the conceptual universe of Judaism.” In this regard he swims against the tide of much recent scholarship, beginning with David Roskies’ breakthrough article “S. An-sky and the Paradigm of Return”—which casts its subject as “a born-again Jew in a Judaism of his own remaking”—and culminating with Gabriella Safran’s magisterial biography, Wandering Soul. Safran shows that An-sky remained profoundly indebted to the ideas and values of Russian Populism even after his alleged return to the Jewish fold, a claim borne out, it seems to me, by An-sky’s exaltation of the Jewish “common folk” and his dream of compiling a “people’s Torah.” Deutsch’s analogies to minhagim books and the geniza, while intriguing, are less persuasive. As regards the latter, neither An-sky nor any of his fellow ethnographers ever intended for their collections to go into hiding; we have the Bolsheviks to thank for that. Nor is there anything distinctly Jewish about cultural treasures being hidden, forgotten, and subsequently rediscovered.

“There is something profoundly Jewish,” Deutsch writes, “about a text consisting entirely of questions.” His introduction makes the case for the deeply Jewish character of An-sky’s project, likening the questionnaire to a Sefer Minhagim (Book of Customs), and the ethnographic collections, with their long period of dormancy behind the Iron Curtain, to a geniza. Like his protagonist, Deutsch seems eager “to legitimate the subject of Jewish ethnography within the conceptual universe of Judaism.” In this regard he swims against the tide of much recent scholarship, beginning with David Roskies’ breakthrough article “S. An-sky and the Paradigm of Return”—which casts its subject as “a born-again Jew in a Judaism of his own remaking”—and culminating with Gabriella Safran’s magisterial biography, Wandering Soul. Safran shows that An-sky remained profoundly indebted to the ideas and values of Russian Populism even after his alleged return to the Jewish fold, a claim borne out, it seems to me, by An-sky’s exaltation of the Jewish “common folk” and his dream of compiling a “people’s Torah.” Deutsch’s analogies to minhagim books and the geniza, while intriguing, are less persuasive. As regards the latter, neither An-sky nor any of his fellow ethnographers ever intended for their collections to go into hiding; we have the Bolsheviks to thank for that. Nor is there anything distinctly Jewish about cultural treasures being hidden, forgotten, and subsequently rediscovered.

Despite his fascination with a book consisting entirely of questions, Deutsch—as he freely admits—can’t help but offer some answers. His voluminous annotations, drawing on primary and secondary sources in multiple languages, valiantly attempt to complete the job that An-sky was unable to finish. To my mind, however, they exhibit a strange literalism, as if answers drawn from academic and other textual sources could possibly substitute for what An-sky was after, which was not just ethnographic data but the idioms of popular belief, their specific tone and texture. As Safran demonstrates in her biography, An-sky was fascinated above all by the visceral power of language and was himself a virtuosic listener and speaker. It is thus odd to be informed, in a footnote to question #1976 (“Is there a belief that the Angel of Death has no power over people when they are learning Torah?”), that “There are a number of rabbinic stories concerning people who frustrated the Angel of Death by learning Torah,” with a citation to the Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic and Roman Period. Nu?

However “Jewish” An-sky’s ethnography may or may not have been, it suggests that being simultaneously the subject and object of an inquiry into customary beliefs is no less fraught than the usual relationship between anthropologist and native. Just as the autobiographer is forced to confront the distance between the experiencing self and the writing self, so the auto-ethnographer must contend with the inevitable gap between informant and interpreter. An-sky knew he was no longer (just) a native. If he had been, he might have answered his own questions.

Suggested Reading

Readjusting Sights

Reams of military history, and recollections by generals have been written on Israel’s many wars, but in this bookish country, Haim Sabato is one of the few Israeli soldiers to write a truly literary memoir.

From the Middle to the End

A deceptively simple novel about a suburban, Midwestern Jewish family catapults into something annoyingly profound.

Secularism and Sabbateans

How did the Jews become modern? Three new books trace the roots of Jewish secularization.

Tragedy and Power

Barry Gewen’s new book argues that Henry Kissinger's "hardheaded Realism” was born of his family’s tragic experience in Nazi Germany.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In