From the Middle to the End

Fiction can provide emotional solace, historical knowledge, a hedge against loneliness, or, simply, pleasure. In The Middlesteins, Jami Attenberg reminds us of another function of literature: It can reduce the enormity of a human life to insignificance, the equivalent of looking at the stars for too long. She accomplishes this through the use of flash-forwards, and they are devastating.

But—and this may surprise—The Middlesteins is a great, light read, a real page-turner. Edie and Richard Middlestein settle in Chicago’s suburbs. They go to synagogue and have a group of similarly Midwestern, middle-class Jewish families as friends. They raise two children, Robin and Benny. Richard is a passively successful pharmacist, and Edie works at a law firm, doing endless pro bono work for the needy and her friends.

Edie also eats. And eats. And eats. So much so she is laid off by her law firm and develops diabetes and heart problems. The chapter titles signal shifts in chronology by tracking Edie’s weight: “Edie, 241 Pounds” comes before “Edie, 160 Pounds,” and “Edie, 332 Pounds” is toward the beginning of the novel. Her family realizes that she is slowly killing herself, but Edie refuses to stop eating. Richard calls it quits, leaving Edie for a new, single life that he hopes includes sex, something he has not had in quite some time. The children are shocked by their father’s betrayal, and, siding with Edie over their father, all but banish him from their lives. Benny and his wife Rachelle step in to help Edie cope; Robin reluctantly agrees to visit once a week.

While we wonder what makes Edie eat and why she won’t stop, we get to know all the Middlesteins, sometimes through delightful set-pieces that are ancillary to the plot. In one, Robin is living in still-ungentrified Brooklyn while working for Teach for America. She and her twenty-something roommates are all equally miserable in their jobs and shocked by the exposure to real poverty. When the apartment becomes infested with bed bugs, they have a ceremonial burning of mattresses in the back alley, after which each girl announces she is moving back home. Robin returns to Chicago, gets a job in a private school, remains single, and drinks too much.

Benny is the cheerful Middlestein, happy in his protected life and his “brick, Colonial style with two sturdy pillars in the front” house. His tightly wound wife, Rachelle, indulges in a bit of pot with Benny at the end of each day.

What did she do all day anyway? She managed a household, and all their possessions. Drove her kids around, Pilates four times a week, an occasional Sisterhood meeting at the temple with all those old ladies who thought they knew everything about everything but only knew something about not much at all if you really wanted to get into it, got her hair done (regular bang trims, coloring once a month), her nails done, her toes, waxing, cooking, shopping. She read books. (She was in three book clubs but she only showed up if she liked the book they were reading.) If you asked her at the right time, she’d say, “Spend my husband’s money.” It was a joke. It was supposed to be funny. But it was true, too.

Her twins, Emily and Josh, are preparing for their b’nai mitzvah over the course of the novel, and Rachelle has placed them in dance classes for the after-dinner, before-the-slide show talent portion of the party. (After much deliberating, she decides on a chocolate fountain because she “would not disappoint her children, her babies, her miracles.”)

Benny, taking after his father, is largely passive and so too is his son Josh, who “would never complain, he would just adapt, until it was too late: the curse of the Middlestein men.” By leaving Edie, Richard takes action, but it is in the form of surrender: he cannot help his wife stop eating, so he gives up.

Attenberg is facile and funny with her descriptions and set-pieces—we go on Internet dates with Richard and to a family Seder with Robin’s boyfriend. We meet a widowed, Chinese strip mall restaurant owner, Kenneth Song, who has been preparing “steaming pork buns, and bright green broccoli in thick lobster sauce” for Edie for years. In a surprising and touching turn, Kenneth falls in love with Edie, and toward the end of the novel he takes a turn at the narration, telling us his story. So too do the temple friends show up near the conclusion for a surprise, bravura performance.

But, from the opening scene, we are worried about Edie. Why does Edie eat? She makes people laugh. She is kind to her children. She does good works. Attenberg is never explicit—and there is no surprising biographical or psychological revelation. Edie seems to overeat because, as the child of a post-World War II Eastern European Jewish immigrant, “food was love,” and plentiful food was a blessing. It seems to afford her a kind of emotional compensation in a family unable to express itself. When teenaged Robin’s friend attempts suicide, Edie doesn’t let her visit him in the hospital—too depressing. For the Middlesteins, the everyday is tenable—one can spend eight months planning a b’nai mitzvah party—but strong emotions are unpalatable. Each female character, at one point in the novel, lets out a scream, and each time Attenberg lets it simply end the chapter.

But Attenberg’s most devastating technique is one that prevents us from ever getting too wrapped up—too emotionally invested—in the lives of the Middlesteins. Every so often—in the middle of a paragraph, while characters are walking along a street or sitting at a table, and after the reader has grown to care about them and their current travails—she flashes forward, shooting way past the ending, to tell us how the lives of the Middlesteins played out decades after the conclusion of the novel. The effect is upsetting and dizzying. Learning about the characters’ futures while we are absorbed in their present, we stop caring about their days. After all, if the characters will just go ahead and die, who cares if there was a chocolate fountain at a b’nai mitzvah party?

When Benny first realizes he is losing his identity—defining full head of hair, he goes to his father’s pharmacy for a prescription.

The two of them wandered uselessly out to the pharmacy; Benny would never step foot into that back room again until after his father had died a decade later, and there was no question that the business would be closed (it probably should have been closed five years before, but Richard had refused, saying that he offered a service to the community, though Benny knew that it was just because he needed a place to go all day), that the dusty shelves needed to be emptied and then tossed out the back door, a painful, clanking, depressing act that Benny, entirely bald by then, accomplished quietly, sadly, on his own. But for now, the Propecia was on the house, and Richard walked Benny to the front door. “So maybe I can come by sometime?” said Richard.

And one finds oneself thrown from wondering whether Benny will go bald to deep questions: What is the purpose of human life? And, more immediately, should I keep reading this book?

But you do because, despite Attenberg’s existential plot-spoilers, you still want to know if Richard comes by Benny’s house and if he finally has sex with the new woman he met on the Internet. Fiction plays tricks with time, and so do we, dilating an afternoon to a decade, forgetting years, imagining the paragraphs of our future.

These flash-forwards catapult this smart, well-written novel into something somehow annoyingly profound. “Just give us the Middlesteins!” one wants to yell—just gently parody suburban living and Midwestern Jews and we will be happy. But Attenberg is not so easy on us. In her novel lurks the sublime. After such knowledge, it seems petty to worry over cholesterol levels, and it makes perfect sense to eat that second dessert.

Suggested Reading

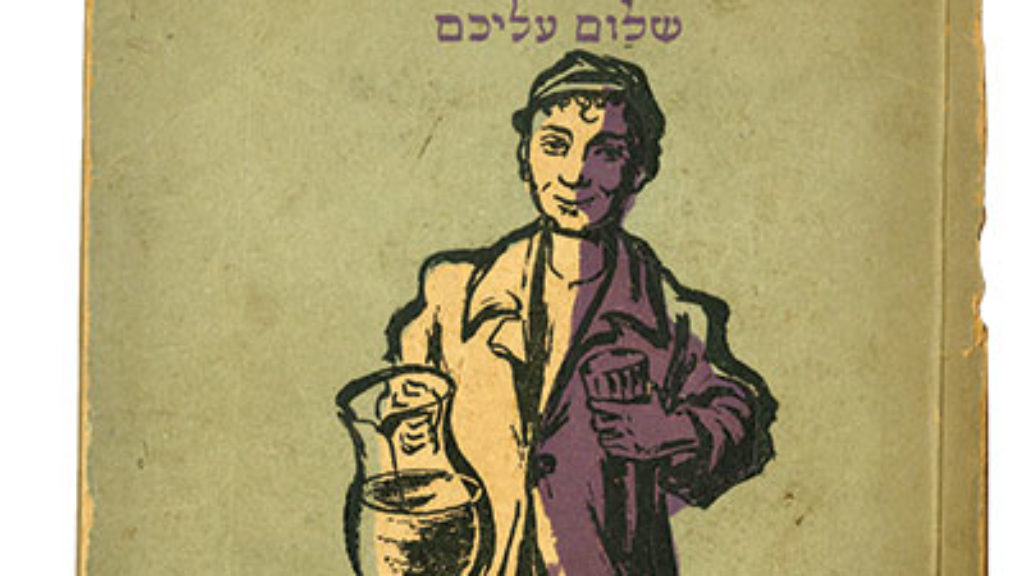

Hebrew School Days

“Of course, I had myself gone to Hebrew school—that’s what we always called it though very little Hebrew was ever learned—through most of elementary school. I’d walk the five blocks down Bancroft . . .”

In the Beginning, There Was Angst

Where a committed secularist would raise up the literary in place of the sacred, Adam Kirsch’s discussions in The Blessing and the Curse read more like a coda to the sacred scriptures.

A Perfect Spy?

Was the original James Bond a Jew from Odessa?

Learning Yiddish After 60

When I was about 10, I had a brilliant idea. If my parents would agree to speak only Yiddish with each other, it would just come to me without effort. I wouldn't have to learn it or study it, I would just wake up one day knowing it.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In