Remembering the Forgotten

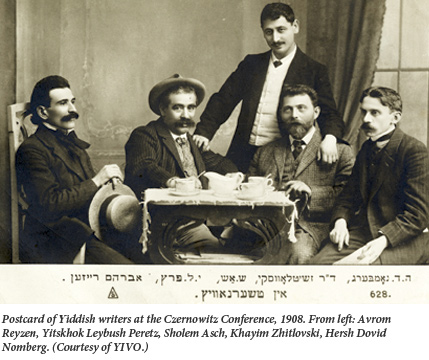

Sholem Asch was, as Bernard Wasserstein tells us, the most popular Yiddish writer of the interwar period and the only one who sold enough books “to buy a villa on the French Riviera (named Villa Shalom), where, clad in his flowered dressing gown, he would greet morning visitors in his garden overlooking the sea.” Even when he was ensconced in luxury, however, he never lost what Wasserstein calls his “deep sympathy for amkho (the common [Jewish] people).” Wasserstein’s own career has been as thoroughly intercontinental as that of Asch (who spent the war years in the United States and later moved to Israel), and he has published many well-received books. Although the British-born professor at the University of Chicago is unlikely to have anything resembling a Villa Bernard on the shores of Lake Michigan, he does match Asch in his affection for the lost amkho of Eastern Europe.

On the Eve: The Jews of Europe Before the Second World War contains numerous and lengthy quotations from Yiddish poems and songs, usually chosen to give voice to the yearnings and fears of the masses. The Jewish socialist Bund, Wasserstein tells us, had the best tunes, and he provides the lyrics to the chorus of the party’s anthem, composed by S. An-Sky, as well as those of “the stirring anthem of the Bundist children’s organization.” We also hear, among many other things, “folk doggerel” about the status of ordinary Jewish women; the song of a prostitute bewailing her fate; a long jailhouse lament; the pioneering song of Soviet-Jewish farmers, newly transplanted in the Crimea (“Yesterday distant neighbors, today so close, Ukrainian farmers, Jewish peasants”); and the “wretched” and “despicable” verses composed by supposed representatives of “the ‘folk'” during the years of Stalin’s rule. These lyrical interludes supply the soundtrack for Wasserstein’s vivid and comprehensive (if somewhat repetitious) overview of the political, social, economic, and cultural lives of Eastern European Jewry in the years leading up to World War II.

On the Eve isn’t only about Yiddish speakers; it reports extensively on more assimilated Polish—and Russian—speaking Jews in the east, and also the Jews of Germany, France, and even the Sephardim in the Balkans and elsewhere in Europe. But we don’t hear their songs and poems, apart from a token selection from the Judeo-Espagnol (the term Wasserstein prefers to Ladino) repertoire.

Wasserstein dutifully notes the disproportionately large contribution made by Jewish thinkers, writers, and artists to the cultures of Western and Central European nations during the interwar years, but he does not revel in their accomplishments. He mentions the French philosopher Henri Bergson, for instance, only once, in passing, and doesn’t refer to Edmund Husserl, Heidegger’s teacher and the founder of phenomenology, at all. The celebrated German and Austrian writers Emil Ludwig and Stefan Zweig make nothing more than cameo appearances in On the Eve. Franz Kafka, to be sure, shows up several times, not so much on account of his literary achievements as because of his admiration for the Eastern European Jews who crossed his path. Early on, Wasserstein quotes Kafka’s proclamation that he “would like to run to these poor Jews of the ghetto, kiss the hems of their garments and say nothing, absolutely nothing. I would be perfectly happy if they would endure my presence.” Then again, more than two hundred and fifty pages later, Wasserstein reports what he wrote in the aftermath of his encounter with a hundred Eastern European Jewish war refugees in the Jewish Town Hall in Prague: “If I’d been given the choice to be what I wanted, then I’d have chosen to be a small East European Jewish boy in the corner of the room.”

Wasserstein doesn’t fail to note that Martin Buber had similarly strong feelings about the eastern Jews, but he writes mockingly of the “foggy, völkisch romanticism” that colored his portrayal of the Hasidim. He says almost nothing of the philosopher Franz Rosenzweig or of the “renaissance of Jewish culture” that took place—according to the historian Michael Brenner and others—during the years of the Weimar Republic. But he does note that there was “talk of a renewal of Judaism” during the first years of Nazi rule. By 1937, however, on the brink of his departure from Germany, Rabbi Joachim Prinz “was lamenting the shallowness and brevity of the phenomenon.” Wasserstein cites Prinz’s disparaging words with apparent approval.

While he does not spend much time celebrating Jewish cultural icons or Jewish culture in the western and central parts of Europe, Wasserstein relates with relish the stories of men with unusual careers, whatever their point of origin. No one who knows his work will be surprised to find in this book a brief depiction of Trebitsch Lincoln, the Hungarian-born Jew (about whom he has written a wonderful biography) who became, among other things, a member of the British Parliament in 1910, a member of a short-lived extreme right-wing government in Germany in 1920, and a Buddhist monk in Shanghai.

On the Eve describes such similarly fascinating characters as Yitzhak Farberowic and Isaac Steinberg. The former was a yeshiva dropout with a criminal record who, under the name “Urke Nakhalnik”—impudent thief, in Polish-published an autobiography entitled My Life: From Yeshiva and Prison to Literature. The latter, the commissar of justice in Lenin’s first government, “combined revolutionary socialism with Orthodox Jewish observance.” After leaving Russia in 1922, he became the leader of the territorialists, who sought to establish a Jewish homeland somewhere other than Palestine.

Wasserstein’s book is full of delicious tidbits. “In 1935,” he informs us, “plans were afoot in Vilna to publish a newspaper, Der yidishe schnorrer, that would represent the interests of beggars.” In 1937, Matvei Khavkin, the Communist Party chief in the Jewish autonomous region of Birobidzhan, was removed from office and arrested in part for “greeting a comrade with the words Gut shabbes.” Mrs. Khavkin was then committed to a mental asylum for allegedly having tried “to poison the Moscow party chief, Kaganovich, with homemade gefilte fish when he came to dinner during his visit to Birobidzhan” back in 1936. I am afraid, however, that I cannot share any more of this without misrepresenting Wasserstein’s book. For these oddities, as amusing as they might be, do not prevent it from being a very somber volume.

Almost everything described in the narrative that could excite a sense of admiration for the vitality of the Jewish people turns out in the end, in Wasserstein’s account, to have been either in decline or mired in futility. Even where it remained the dominant trend, Orthodoxy was fading, with synagogues deserted by the young and yeshivas heading for bankruptcy. In the western countries, it had been all but abandoned; in the Soviet Union, the government had virtually stamped it out.

Yiddish culture, apparently flourishing in many places, was in reality on the defensive. “Even in Vilna, the citadel of Yiddish, just 8 percent of the loans from the Mefitsei Haskalah Library in 1934 were of Yiddish books.” After visiting a Yiddish theater in Warsaw in 1938, the American Yiddish writer Joseph Opatashu noted that “Yiddish resounded to the rafters from the stage yet the audience in the stalls and the actors behind the scenes all whispered to one another in Polish.”

Despite his evident disdain for the Soviets, Wasserstein freely acknowledges that until the late 1930s they “had done more to promote Yiddish than any other government in history.” But the Soviet Jews themselves, in their eagerness to assimilate and advance within their new society, voted with their tongues and switched en masse to Russian. Both in Poland and in the Soviet Union the production of Yiddish books was in steep decline by the late 1930s. And “even more than Yiddish,” Judeo-Espagnol was simultaneously “losing ground to the national languages of the states where Jews lived.”

Everywhere, the Jewish family was shrinking and increasingly falling apart. Even in Eastern Europe the Jewish birthrate “is estimated to have halved between 1900 and the late 1930s.” Divorce rates were rising, as was intermarriage. After providing some reliable statistics, Wasserstein asserts that “intermarriage, on the scale and in the form that it took in Central Europe in the interwar period, thus portended the rapid disappearance of the Jewish community.” And in the Soviet Union, by 1939, “out of every thousand marriages in which one partner was a Jew, 368 were mixed.”

On top of all of these problems, the Jews had enemies—everywhere. In a chapter combatively entitled “The Christian Problem,” Wasserstein surveys the menacing development of anti-Semitism not only in Hitler’s Germany but also throughout Europe (apart from the Soviet Union). In other chapters, he reviews the Jews’ unsuccessful efforts to develop a political response to a situation that was universally grim. He does not cast any blame, probably because he believes that a “wholly defenseless and largely friendless” people was inevitably going to find itself at the mercy of the “barbarians.” But Wasserstein does seem to be particularly irritated by the Zionists’ pretensions. If, after 1936, he asks, they found it difficult to secure entry to Palestine for even a limited number of committed and trained young people, “how could the movement plausibly claim to offer a solution to the plight of the broad masses of the Jews in Europe?” One of the last chapters of On the Eve, entitled “In the Cage, Trying to Get Out,” presents a not unfamiliar but nevertheless wrenching description of many desperate attempts, at the end of the interwar period, to escape that plight.

Reading On the Eve, I often found myself recollecting scenes from a very fine documentary about Polish Jewry between the wars that I have watched (and screened in classes) many times called Image Before My Eyes. Like the filmmaker, Josh Waletzky, Wasserstein has sought to go back before the Holocaust and “to capture the realities of life in Europe in the years leading up to 1939” for the Jews of that time. One could easily imagine Waletzky saying of his film what Wasserstein says in the introduction to his book:

The fundamental objective has been to restore forgotten men, women, and children to the historical record, to breathe renewed life momentarily into those who were soon to be dead bones.

Indeed, many of the individuals and topics highlighted in the film are central to On the Eve as well. More than one of the Yiddish songs transcribed in the book can be heard in Image Before My Eyes, either in the voice-over or as performed by one of the many (now in all likelihood deceased) interviewees who participated in the film-making. Waletzky, of course, confined himself to Poland, while Wasserstein ranged throughout the European continent.

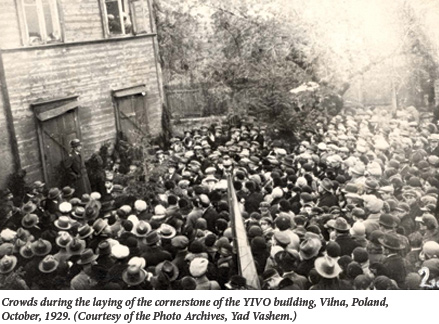

The greatest difference between Image Before my Eyes and On the Eve lies, I believe, in tone. While the film occasionally borders on a sort of posthumous boosterism, the book never fails to remind one of the dark side of even the most impressive achievements. To take but one example, Waletzky includes video footage of the dedication of the YIVO library in Vilna in 1929. Exultingly, the narrator identifies founder Max Weinrich and the other Yiddish cultural heroes who appear on the dais. It is only from Wasserstein that we learn how much “trouble YIVO encountered in raising the $3,500 needed to erect its building in Vilna,” and that “YIVO—and Yiddish secular culture in general—lived in a state of chronic financial crisis.” True, “against the odds,” YIVO did succeed by 1933 in raising $10,000 and constructed the beautiful building one can see in the documentary. But Wasserstein also reports that the great Jewish historian Simon Dubnow “sadly concluded after a visit in 1934,” that “YIVO in Vilna remained ‘a small island of culture in a sea of beggary.'”

If I continue to teach a survey course in modern Jewish history, I won’t be so foolhardy as to replace my in-class screening of Image Before My Eyes with an assignment to read Wasserstein’s sad but reliable 500-page volume. But if, as often happens, I see some students who find it difficult to stand up and leave the room after having been absorbed for an hour and a half watching “those who were soon to be dead bones,” I’ll know what book to suggest to them.

Suggested Reading

The Banality of Evil: The Demise of a Legend

As The New York Times noted, Bettina Stangneth’s newly translated book Eichmann Before Jerusalem finally and completely undermines Hannah Arendt’s famous “Banality of Evil” thesis.

Pessimism Not Despair: A Reply to My Critics

"Just as the turmoil aroused by Israel’s new government has overlooked the Palestinian issue while concentrating on a more immediate crisis, so have the responses to my article."—Halkin writes back.

History, Memory, and the Fallen Jew

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi predicted a day when the historian would give his task over to the poet. A retrospective look at his writings show his own struggle between the claims of academic history and Jewish memory.

Yehuda Amichai: At Play in the Fields of Verse

Yehuda Amichai was an exuberant person with a lively, impish sense of humor. He was, at the same time, a melancholy man. Both traits are present in his poetry.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In