Reorientation

Middle Eastern studies in this country is dominated by the Saidians,” complained the doyen of traditional Middle East historians Bernard Lewis in a recent interview in The Chronicle of Higher Education. “The situation is very bad. Saidianism has become an orthodoxy that is enforced with a rigor unknown in the Western world since the Middle Ages. If you buck the Saidian orthodoxy, you’re making life very difficult for yourself.”

If this is indeed the rule in American academia, Jacob Lassner is undoubtedly one of a small, but by no means insignificant cohort of notable exceptions to it. Although he devotes only a few pages of his new book to direct combat with Edward Said, its first half constitutes in many respects an extended and unabashed defense of what the late professor of English at Columbia so successfully stigmatized as “Orientalism,” a clever but misleading conflation of the name of a 19th-century romantic movement in art and belles lettres and the academic discipline of Oriental studies. In the second half, Lassner practices what he preaches with respect to his main area of expertise, the history of the Jews and Christians in the medieval Muslim world.

Despite Lassner’s claim that it is “modestly conceived,” this book is a very substantial undertaking, tightly packed with both detail and analysis. Sketching the history of Oriental studies, Lassner devotes special attention to the pivotal contribution of European Jewish scholars in the 19th and 20th centuries to the development of modern Islamic studies. This began in Germany with Abraham Geiger, better known today as one of the founding fathers of Reform Judaism, whose doctoral dissertation was entitled “What Did Muhammad Borrow from Judaism?” “Geiger brought to bear his vast knowledge of post-biblical Jewish texts, that is, the rabbinic permutations of biblical narratives that made their way into Muslim scripture.” He was the first Westerner to view Muhammad as a sincere religious individual and not a cynical charlatan, as Europeans had maintained since the Middle Ages. Among his many successors was Ignaz Goldziher, the Hungarian Jew who is to this day widely regarded as the father of Islamology. The role of all of these scholars “in advancing our knowledge of Islam and the Muslims,” Lassner tells us, “was substantial if not indeed central to the larger orientalist project.” What really defined this project, however, was not the ethnic origin of some of the scholars involved in it but the broad range of its aims and accomplishments.

Apart from exploring the origins of Islam and its relation to its monotheistic predecessors, the orientalists reawakened interest in “disciplines of a distinctly Islamic character that had become undervalued by their Muslim contemporaries, for example, Arabic historical writing.” They produced, among many other things, outstanding critical editions of long-neglected Muslim classics like the writings of the great medieval historian Ibn Khaldun. Far from confining themselves to written texts, they took an “active interest in cataloging and studying Islamic painting, pottery, metalwork, carpets, and the like, not simply as collectable objects of treasure but as significant markers of Islamic cultural production.”

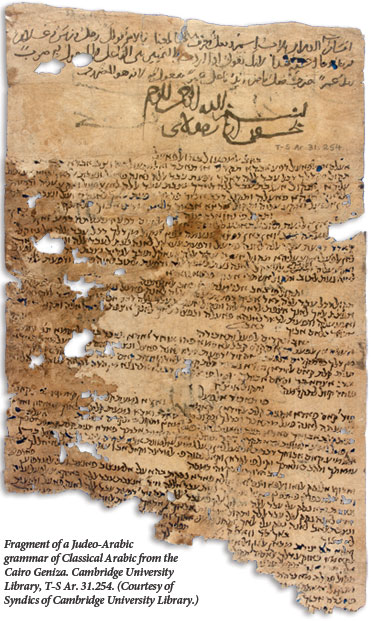

Scholars, like the late S. D. Goitein, have already opened new vistas into the daily life of the medieval Islamic world, and as they continue to comb through the “neglected trove of more than 100,000” Arabic papyri, and many thousands of Judeo-Arabic documents from the Cairo Geniza, they may yet succeed in “reconstructing the fabric of economic and social life to which other Arabic literary sources pay inadequate attention.” Instead of “colonizing Islamic scholarship,” as the people Bernard Lewis labels Saidians have contended, “orientalists and their successors liberated it for the benefit of worldly Arab Muslims and Christians” and indeed for all humanity.

Unfortunately, however, “worldly” Arabs who might be receptive to the teachings of the orientalists are in short supply. This is not the fault of Said and his disciples, unhelpful as they have been. Lassner dismisses their work, but appears to disagree with Lewis (whom he admires) about the damage they have done. Most “philologically grounded specialists in Near Eastern history and religious institutions” never fell under their influence, he maintains, and today Said is increasingly subject to criticism, even in Arabic-language scholarship.

If the orientalists’ influence has failed to penetrate very deeply into the contemporary Arab world, it is not because the post-colonialists have stood in their way but because of the opposition stemming from the local guardians of Muslim tradition. They reject out of hand “the challenge presented by orientalists and their historical methods to Muslim self-understanding and behavior.” It is Lassner’s impression, however, that they are no longer very much disposed to rail against it. “Over time,” it seems to him, “they have become more confident of their ability to insulate the believers from the depraved views of the Western academy and its intellectual camp followers.” This, at any rate, is Lassner’s assessment of the situation in the Arab heartland of the Muslim world. More “interesting reactions of Muslims to Oriental studies and the challenges of modern culture are taking place,” he informs us, in Southeast Asia, Turkey, and Iran. But Lassner leaves discussion of these developments to others.

One thing Lassner is fully prepared to review, however, is the overall situation of Jews and Christians in the medieval Muslim world. In treating this subject, it is not his intention to make (what would be for him) yet another contribution to the scholarship but to provide an informative and footnote-free, yet reliable and up-to-date survey for the benefit primarily of “intellectually curious readers outside the academy.” What such readers should not be led by this announcement to expect, however, is simple and definitive answers to all of the complex questions he raises.

Lassner is extremely reluctant, for example, to arrive at firm conclusions with regard to what actually happened during Muhammad’s hostile—and in one famous instance bloody—encounters with the Jews of Arabia. The traditional Muslim accounts of these events were set down in writing at least a century after they occurred and, for reasons that Lassner skillfully elucidates, cannot be taken at face value.

Lassner generally deals with these sources with great respect, but sometimes allows a little humor to peek through his review of them. He mentions, for instance, the story of the Jewish woman from the oasis of Khaybar who gave Muhammed poisoned donkey meat after his slaughter of the Jewish forces there.

One could readily understand, given tribal sensibilities, why she would have chosen to avenge her murdered kinfolk. However, in this case, the meat would appear more seasoned with irony than any deadly substance. So delicate was the poison applied, the Prophet only succumbed to the tainted meat some four years later.

Unfortunately, this tale and other less laughable reports laid the lasting foundations for popular and scholarly perceptions of Jews that were generally more negative than those that Muslims held of Christians.

Of the many subjects that Lassner discusses, the one that is likely to be of most interest to his target audience is the question of “tolerance and coercion in medieval Islam.” While acknowledging that apart from the rough treatment accorded to the Jews by Muhammad himself, “there was little in the Jewish experience under medieval Islamic rule to compare with the likes of the periodic Jewish persecution in Europe,” Lassner does not leap to unwarrantedly sunny conclusions. He neither celebrates a “Golden Age” of Jewish-Muslim coexistence, nor advocates the “neo-lachrymose” vision of unmitigated Jewish subjection and suffering under Islamic rule.

Despite the best efforts of some modern Muslim scholars to locate in their traditional texts something like the “kind of tolerance trumpeted by liberal forces in the democratic societies of the West,” medieval Muslims were quite far from offering “a blanket acceptance of others and their religious views and behavior.” But even as he demonstrates the vast differences between the situation in the medieval Muslim world and the most enlightened modern societies, Lassner rightly notes that “in the best of times during the formative period of medieval Islam, the three monotheistic faiths interacting with each other produced a vibrant civilization to which the entire world remains deeply indebted until this very day.”

After observing that the Islamic world ultimately failed to capitalize on its own medieval scientific and philosophical heritage, Lassner concludes with the hope that it will once again be able to draw creative inspiration from outside and find a synthesis between Islamic belief and modern science and innovation. He even entertains the hope that perhaps Jews—this time the Jews of the technologically dynamic state of Israel—will once again play a part in this project. After all, “some early Zionist and current Israeli visionaries saw and continue to see the Jews as playing a central role in the transfer of valued knowledge. In this idealized vision, the intellectual traffic will flow once more over a Jewish bridge that connects the Muslim East and the Christian West.”

While he ends his thought-provoking book with these optimistic musings, Lassner knows all too well what obstacles stand in the way of their realization. “The recent Islamic revival has created internal issues still to be settled within the Abode of Islam,” he writes at the end of his book, in characteristic understatement.

Suggested Reading

Early Modern Blasphemy and Postmodern Virtue

Was Jacob Frank a progressive trendsetter or a seductive cult leader?

Smitten with Sympathy

As the sea split, God shushed the angels, saying, “My handiwork is drowning in the sea and you are reciting songs before me?”

Something Antigonus Said

When the Saducees misinterpreted Antigonus of Sokho, they lost eternity--at least that's what the Rabbis thought.

Perpetual Motion

Remembering Yaakov Elman, who changed the way we study Talmud.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In