State and Counterstate

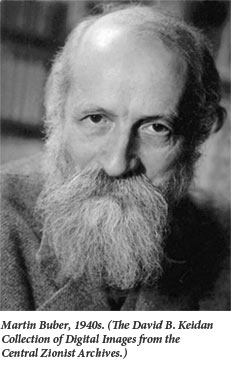

A little more than a decade ago, Yoram Hazony caused something of a stir with the publication of The Jewish State: The Struggle for Israel’s Soul. Hazony, founder of the Jerusalem-based Shalem Center, denounced the post-Zionists in the Israeli academic world for conducting a “systematic struggle . . . against the idea of the Jewish state, its historic narrative, institution, and symbols.” He also controversially traced this trend back to Martin Buber and a number of other Central European-born Jewish intellectuals associated with the Hebrew University and Brit Shalom who advocated for a binational Arab-Jewish state from the 1920s through the 1940s. Hazony neither portrayed these people very accurately nor proved that they had the influence that he attributed to them. But whatever its failings as intellectual history, his book seems to have had an influence on at least some post-Zionists. In the years since Hazony’s book was published, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of people celebrating Buber and similar figures for their prescient criticisms of political Zionism, and their dreams of something better.

The latest professorial antagonists of Zionism do not, to be sure, give full credit where Hazony thought blame was due, but they often see Buber and the others as being in some sense forerunners of their own line of thinking. In The Question of Zion, for instance, the British scholar Jacqueline Rose prefaces a brief treatment of some contemporary Israeli adherents of the binational idea with an expansive and sympathetic account of Martin Buber, Hannah Arendt, Hans Kohn, and Ahad Ha’am as the proponents of a Zionism that “had the chance of molding a nation that would be not an ‘expanded ego’ but something else.” Rose maintains that their associates in the Zionist movement had the opportunity to adopt this model and laments the fact that they “did not take it.”

Why not, she does not immediately explain, thus leaving the impression that the fault lay entirely with the deluded and power-hungry political Zionists she devotes most of her book to psychoanalyzing. Rose makes no mention in this context of the complete lack of interest on the part of the Palestinian Arabs in anything that her heroes had to offer. Only once, toward the very end of the book, does she briefly note that the Arabs too played a part in rendering binational coexistence impossible.

When she is not writing about Zion or actively lobbying against it, Rose earns her living as a professor of literature, not a historian, and therefore cannot be faulted too much for such errors as describing the Jewish Labor Bund as “the group of socialist Jews virulently opposed to Jewish nationalism” (they were, in fact, nationalists), claiming that in 1893 Herzl actually put before the Pope a plan to convert all the Jews (he only daydreamed about doing so), and transforming the 18th-century Sabbatean leader surnamed Frank from a Jacob into a Joseph (like the biographer of Dostoevsky).

At least Rose makes no pretense of being a contributor to Jewish thought in her own right. The same cannot be said of another professor of literature who has also become an anti-Zionist polemicist, Judith Butler. The renowned author of many works of critical and feminist theory, Butler is, among other things, the Maxine Elliot Professor in the Departments of Rhetoric and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley and the Hannah Arendt Professor of Philosophy at the European Graduate School in Switzerland. After having reiterated on a number of different occasions her annoyance at the equation of Jewishness with Zionism, she has now written a short piece entitled “Is Judaism Zionism?” Recently published in a book entitled The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere, the essay arrives at a predictably negative answer.

At least Rose makes no pretense of being a contributor to Jewish thought in her own right. The same cannot be said of another professor of literature who has also become an anti-Zionist polemicist, Judith Butler. The renowned author of many works of critical and feminist theory, Butler is, among other things, the Maxine Elliot Professor in the Departments of Rhetoric and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley and the Hannah Arendt Professor of Philosophy at the European Graduate School in Switzerland. After having reiterated on a number of different occasions her annoyance at the equation of Jewishness with Zionism, she has now written a short piece entitled “Is Judaism Zionism?” Recently published in a book entitled The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere, the essay arrives at a predictably negative answer.

Butler has not become an exponent of some familiar strain of anti-Zionist Judaism, such as classical Reform or, needless to say, Satmar theology, but has instead rummaged through the writings of some of the very same thinkers disparaged by Hazony to patch together an innovative anti-Zionist creed. In doing so, she displays a little more erudition than Rose. She gets people’s names right, though she still has some trouble with dates. She refers, for instance, to a “famous debate between Hermann Cohen, the neo-Kantian Jewish philosopher and Gershom Scholem” on Jewish nationalism. Only someone who is unaware that Scholem was merely 21 when Cohen died at the age of 76 could imagine that such a debate ever took place. Her reference to Scholem’s famous challenge to Hannah Arendt isn’t incorrect, but one must object to her statement that “Scholem quickly embraced a conception of political Zionism, whereas Martin Buber in the teens and twenties actively and publicly defended a spiritual and cultural Zionism that, in his early view, would become ‘perverted’ if it assumed the form of a political state.” In fact, throughout the twenties and even into the thirties, as is well known (just check Hazony), Scholem was an outspoken defender of spiritual and cultural Zionism and an opponent of the idea of a Jewish state. It took Scholem decades to come to the conclusion that Nazi persecution and Arab rejectionism left the Zionists with no choice but to establish a state of their own. As he wrote to Arendt in 1946, “The Arabs have not agreed to one solution, be it federal, statist, or binational.”

Why can’t they learn? Why do these post-modern academic worthies who step beyond the boundaries of their disciplines (if this term is at all appropriate here) to discuss their people’s affairs always fail to have their manuscripts vetted by people more in control of the facts? Why are they in such a hurry to move beyond the petty details into grand ideas and utopian preaching?

When she does go to work on more theoretical terrain, Butler takes as her point of departure a teaching of the Lurianic Kabbalah, or, I should say, Hannah Arendt’s 1946 review of Gershom Scholem’s treatment of this subject in his Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. Isaac Luria, remarks Arendt, conceived of the Jews as having a mission of uplifting “the fallen sparks from all their various locations.” According to Butler, what interests Arendt here is “not only the irreversibility of ‘emanation’ or dispersal but the revalorization of exile that it implies.” That, in any case, is what Butler likes about this idea. If the Jews have to be all over the place to uplift the scattered sparks, it is clearly better that they be dispersed among non-Jews than concentrated in their own territory.

Following the clues provided by Arendt and Scholem, Butler pounces on what she thinks is a solid,

traditional foundation for diasporism. And once she has it, neither the Kabbalah nor its interpreters are of any further use to her. They couldn’t be. For the eschatology of Lurianic Kabbalah, its vision of the ultimate collection of all the scattered sparks and the end of exile is utterly at odds with the lesson she wants her sources to supply. Relying on other figures, therefore, especially Walter Benjamin, she veers in the direction of “messianism, perhaps secularized, that affirms the scattering of light, the exilic condition, as the nonteleological form that redemption now takes.”

What does all of this imply for those Jews who aren’t dispersed but already—and regrettably—concentrated in their own state in the land of their forefathers? Pursuing a tortuous path of ethical reflections focused on the virtues of “dispossession from national modes of belonging,” Butler arrives at the conclusion that “the ongoing and violent project of settler colonialism that constitutes political Zionism” has to give way to “a new concept of citizenship,” and “a rethinking of binationalism in light of the racial and religious complexity of both Jewish and Palestinian populations.” Butler is perspicacious enough to acknowledge the possibility that this might entail “too much risk” for the Jews in question and might even “threaten Jewish life with destruction.” But since it is what justice and secularized non-teleological redemption requires, it must be undertaken, whatever the consequences.

Such puerile reflections are, of course, far from unusual in the realm of radical discourse in which Butler is a celebrity. They would not be at all worthy of sustained criticism were it not for the fact that they appear in a volume from Columbia University Press that also includes pieces by such luminaries as Jürgen Habermas, Charles Taylor, and Cornel West. These essays are expanded versions of talks that were given at a public event in New York City on October 22, 2009. The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere also includes “edited transcripts of dialogues between the authors” that took place in the course of almost five hours of conversation on that day. I would like to believe that at some point in those long discussions someone on the stage or in the audience called into question Butler’s ill-informed, facile, and cold-hearted repudiation of the Jewish state. I am sorry to have to report that no one does so in the published volume.

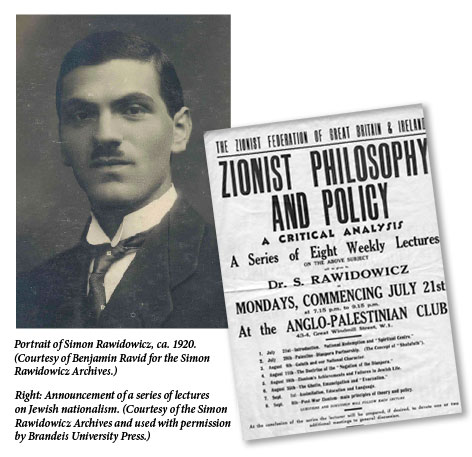

In his book Between Jew and Arab, the prominent Jewish historian David N. Myers has no occasion to refer to Butler, but he does at one point take Jacqueline Rose to task for her demonstration of “inadequate historical nuance and knowledge” in The Question of Zion, even as he commends her for advancing criticisms of Zionism that “cannot be summarily swept away.” Observing that her book, like his own, returns to the outlooks of Ahad Ha’am, Hannah Arendt, Martin Buber, and Judah Magnes, he both notes and excuses her omission of the little-known Simon Rawidowicz from her roster. Myers himself devotes prodigious efforts to recovering the “lost voice” of this man who “poured out his soul over, but ultimately published nary a word about, the Arab Question.”

A Polish-born scholar and thinker, Rawidowicz might perhaps have shown up on Yoram Hazony’s list of rogues had he obtained the professorship in Jewish philosophy at the Hebrew University that he sought during the interwar years. Instead, he went to England and, eventually, to Brandeis University, where he helped to establish its Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies. Toward the end of his rather lonely intellectual life (he frequently used the Hebrew pen-name “Ish Boded,” a solitary man) Rawidowicz composed his never-translated nine-hundred-page magnum opus, Babylon and Jerusalem in a rather arcane Hebrew. This book, as Myers puts it, “combined a re-narration of Jewish history, especially a revaluation of the First and Second Temples, with an extended ideological meditation on Jewish life in his day.” Without ever ceasing to be a Zionist, Rawidowicz affirmed the existence and the cultural importance of a vital Jewish diaspora alongside the Jewish state. For him, the Jews were and ought to remain, in Myers’ words, “a dual-centered” nation.

A Polish-born scholar and thinker, Rawidowicz might perhaps have shown up on Yoram Hazony’s list of rogues had he obtained the professorship in Jewish philosophy at the Hebrew University that he sought during the interwar years. Instead, he went to England and, eventually, to Brandeis University, where he helped to establish its Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies. Toward the end of his rather lonely intellectual life (he frequently used the Hebrew pen-name “Ish Boded,” a solitary man) Rawidowicz composed his never-translated nine-hundred-page magnum opus, Babylon and Jerusalem in a rather arcane Hebrew. This book, as Myers puts it, “combined a re-narration of Jewish history, especially a revaluation of the First and Second Temples, with an extended ideological meditation on Jewish life in his day.” Without ever ceasing to be a Zionist, Rawidowicz affirmed the existence and the cultural importance of a vital Jewish diaspora alongside the Jewish state. For him, the Jews were and ought to remain, in Myers’ words, “a dual-centered” nation.

Rawidowicz has for decades exerted “a kind of hypnotic hold” over Myers, who has in the past contemplated writing a full-fledged biography. Here, he confines himself to a study of one chapter in Babylon and Jerusalem, the chapter dealing with relations between Jews and Arabs in British Mandate Palestine and Israel. For reasons that can no longer be ascertained, this chapter was not included in Rawidowicz’s book when it was published in 1957, the year of his death. It appears in print for the first time, in any language, in Myers’ book.

The chapter, entitled “Between Jew and Arab,” is a lament over Zionism’s loss of innocence in 1948 and a formula for regaining it. The inexcusable offense against morality was not, in Rawidowicz’s eyes, the creation of a Jewish state (which he supported) but the removal of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs from its territory, or rather, the refusal to re-admit the 1948 refugees to what became Israel after the War of Independence ended. On the basis of what Myers calls a “mix of moral and pragmatic considerations,” Rawidowicz passionately pleaded for Israel’s Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and the leaders of Israel to allow every single Arab refugee who had formerly resided in what had become the State of Israel (with the exception of those who constituted obvious security risks) to return home.

“Is it not,” Rawidowicz declared, “the first negative commandment incumbent on any Chosen People: Do not uproot a man from his possessions, whether he is a member of your people or not? Everyone (Jew or not) is called ‘man.’ Do not build yourself up from the destruction of one who is weaker than you. Conquer your impulse to dominate, as well as all lesser impulses, and perhaps you can become a Chosen People.” Those who fear that obedience to such a commandment would jeopardize the security of Israel ought to consider the alternative. The readmitted refugees might constitute a danger inside the state, “but they are also a danger outside of the state: and this latter danger is many times more serious than that within the state.” Nothing, Ravidowicz argued, could be as bad as the menace posed by “hundreds of thousands of refugees who dream night and day, by virtue of their stateless existence, of the possibility of creating a state right now, of realizing this goal in the immediate future.”

The danger in which Israel’s refugee policy places its inhabitants was accentuated, according to Rawidowicz, by the one in which it placed Jews living in other countries. If the State of Israel was as responsible for the well-being of Jews outside its borders as David Ben-Gurion maintained, then didn’t this responsibility “compel it to regard the plight of the refugees from the standpoint of the Jews in the diaspora, of their struggle for rights in Gentile countries, whether the rights be those of a citizen or of a national minority?”

For Rawidowicz, the moral question clearly outweighed such pragmatic concerns, and this appears to be the case also for Myers, who acknowledges that his book stems largely from his moral uneasiness over the state of Jewish-Arab relations. In the introduction, Myers shares his own reservations about some of Rawidowicz’s pragmatic arguments as well as his doubts about whether his “call for the repatriation of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees is practicable in the current political climate.” But Myers never raises any doubts about the correctness of Rawidowicz’s moral judgment.

Nor does he say as much as he might have said to elucidate its foundations. On encountering numerous references to God, the Holy One, and the Guardian of Israel, Rawidowicz’s reader must wonder whether these words are to be taken literally or amount to nothing more than a Hebraic humanist’s rhetorical flourishes. Rawidowicz, Myers informs us, received an Orthodox upbringing, but by the 1920s had “moved away from the personal ritual practice of his father’s home.” But where did he land? Myers never comes closer to an answer than when to tell us that Rawidowicz, unlike Buber, was “not especially interested in the task of rejuvenating the Jewish religion.” He was, after all, a man whose “distinctive version of Jewish nationalism” constituted an “effort to negotiate between . . . Ahad Ha’am and Simon Dubnow,” two undoubted freethinkers. It seems, then, that his morality lacked any real religious support and has its ultimate source in what Rawidowicz saw as the essential or historical superiority of Jacob’s moral sense over that of Esau.

Myers does in fact betray a hint of discomfort with Rawidowicz’s ethnocentric brand of morality when he refers to his “unreconstructed vision of Jewish exceptionalism.” But he is not eager to call into question its underpinnings. Nor does it bother him unduly that his “broader political thought” does not represent “a fully developed or systematic political theory,” or that Babylon and Jerusalem “often has a haphazard feel to it, mixing the historical and the contemporary, the philosophical and the impressionistic, the familiar and the novel.” He is, it seems, too grateful for Rawidowicz’s “uncommon moral voice” to say anything that might diminish its authority. Yet he is not exactly prepared to reiterate what it demands in his own name—or, for that matter, to reject unequivocally its key demand. In language that echoes his introduction, Myers repeats in his epilogue that “Rawidowicz’s proposal for the repatriation of hundreds of thousands of refugees is not practicable in the present context.” Two paragraphs later, however, he reopens this twice-shut window at least a crack when he restores to tomorrow’s negotiating table “the gamut of options ranging from compensation and property restitution to partial or full return (to the State of Israel or, more likely, to a future state of Palestine).”

David Myers characterizes Rawidowicz’s call for Israel to repatriate virtually all of the Palestinian refugees a “bold” one, even though he refrained from issuing it in public. He himself never casts any doubt on Rawidowicz’s contention that Jewish morality requires such action. He does dismiss, more than once, the possibility that mass repatriation is feasible, in the “current political climate” or “in the present context,” at any rate. But he also seems to hint at the possibility that existing impediments to Rawidowicz’s just solution may yet dissolve. While one can, in the end, credit Myers with more boldness than his hero, in that he published his ideas, one cannot help but wonder whether he is showing himself to be a bit less bold by muffling them. It seems much more likely, however, that Myers is placing all his cards on the table when he proclaims that the point of his book “has not been to square the circle with a Solomonic policy recommendation” but simply to let Simon Rawidowicz’s voice be heard.

Rawidowicz’s favorable evaluation of the Jewish diaspora and, to a much lesser extent, his views on the Israel-Arab conflict, are among the subjects discussed in a book that has grown out of a doctoral dissertation that Myers enthusiastically praises in his introduction, Noam Pianko’s Zionism and the Roads Not Taken: Rawidowicz, Kaplan, Kohn. Similarly to Myers, Pianko speaks of Rawidowicz’s “rather speculative and unsystematic treatment of Jewish political thought.” But he digs deeper into it, showing that beneath the veneer of traditional Jewish references it has its roots in a complex mixture of Enlightenment and anti-Enlightenment ideas. On the one hand, Rawidowicz is a defender of “the basic universal principles of equality and individual rights that had been championed by 18th– and 19th-century idealism.” On the other hand, he relies heavily on “myth as a source of truth,” even if it is connected with a narrative, like the traditional account of Jewish history, one knows to be historically inaccurate. “Rawidowicz’s effort to maintain the myth and an awareness of its historically constructed nature,” according to Pianko, helps us to understand “his decision to present his political theory through symbols and metaphors, rather than directly importing Western philosophical terms.”

This helps explain what is happening when Rawidowicz utters (or should one say mutters?) his prophetic-style admonitions to the leaders of the Jewish state, even though it is not Pianko’s main interest in Rawidowicz. What primarily disturbs Pianko is the Jewish state’s exercise of a kind of eminent domain over the concept of Jewish nationhood. His aim is “to rehabilitate and revive,” for the sake of diaspora Jewry, “dissenting streams of Zionist thought that offer models of Jewish nationality as distinct from, and even defined in opposition to, the nation-state model.”

Rawidowicz, we learn, developed his model of what Pianko dubs “global Hebraism” in an effort to salvage the Jews’ future. In opposition to “state-seeking” Zionists who called for the concentration of all the world’s Jews in a nation-state of their own or even argued that the Jewish state should be the center of the Jewish world, he “advocated for building Jewish national centers in the diaspora as well as in Palestine.” His reasons for doing so were primarily cultural and had to do with keeping open the conduits by which non-Jewish ideas could, in the proper measure, enter Jewish national consciousness. In addition, by demonstrating how it was possible to maintain both cultural distinctiveness and openness in different centers in many polities, Jewish communities throughout the world would be able not only to flourish but to constitute, in Rawidowicz’s own words, “a blessing” to the “non-Jewish environment.”

The second “counterstate” thinker Pianko discusses is Mordecai Kaplan, the founder of Reconstructionist Judaism. Arguing that Arthur Hertzberg did him something of a disservice when he called him the man who epitomized American Zionism, Pianko points to his “far more complex relationship” with the movement, which entailed “deep reluctance about, and even opposition to, statehood.” To illustrate this point he quotes Kaplan’s declaration in 1948 that the proper objectives of Zionism “do not and need not require the sort of irresponsible and obsolete national sovereignty that modern nations claim for themselves.” Pianko ought to have made it clearer than he does that Kaplan later acknowledged that events “have compelled us Jews to establish a state.” But his failure to do so is nothing more than a reflection of the fact that his main interest in Kaplan lies elsewhere, in his conception of Jewish life in the modern diaspora.

A realist and a pragmatist, Kaplan knew that he had to “kowtow” to “the American Jewish synthesis” and restrict the “more radical claims of nationality . . . by juxtaposing religion with civilization.” In the framework of “his larger agenda” religion “served the functional purpose of providing the philosophical, and even theological, justification for the existence of particular national communities that operated outside nation-state categories.” What is especially useful to Pianko in Kaplan’s work is his depiction of a “civilizational model of nationalism,” which is based upon “land; language and literature; mores and laws; and folkways, folk sanctions, and folk arts,” but not necessarily “statehood, spirit or culture, and descent.” Pianko welcomes this diluted form of nationalism as a means of replacing a state-centered vision with one focused on a “patchwork of national communities with members dispersed across political and territorial boundaries.” He is grateful to Kaplan for simultaneously devaluing sovereignty and ratifying the equal status of all the amorphous nation’s component parts.

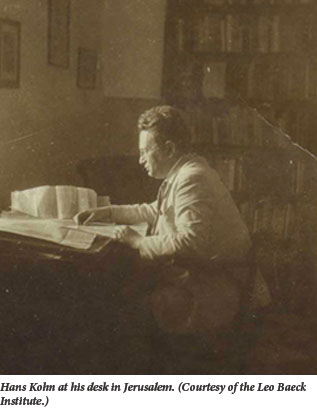

The appearance of Hans Kohn as the third person on Pianko’s short list of 20th-century thinkers who offered better models of Jewish nationality is something of a surprise. A Prague-born cultural Zionist and a supporter of the creation of a binational state in Palestine, Kohn moved to Jerusalem in 1925 and served for years as the director of propaganda for Keren Hayesod, the fundraising arm of the World Zionist Organization. In the aftermath of the anti-Jewish riots of 1929, however, he became convinced that Zionism could overcome Arab resistance and secure its future only by pursuing a militant course that he as “a Jewish human being” and a pacifist could not follow. He eventually moved to the United States, where he earned, as Pianko puts it, a well-deserved “reputation as the founder of a civic nationalism that stands in direct opposition to ethnic or cultural varieties.” Indeed, among students of nationalism, Kohn’s name has become virtually synonymous with this distinction, one that contrasts liberal, western and supposedly supra-ethnic variants of nationalism with illiberal, eastern ones, and thereby stigmatizes Zionism as essentially retrograde.

Pianko nevertheless maintains that Kohn remained a Zionist and that his later “formulations of Jewish nationalism are more closely linked to other counterstate theories of Zionism than it initially appears.” He supports this surprising assertion with a reference to Kohn’s 1957 book American Nationalism, which includes, he tells us in an unfortunate bit of dissertation-speak, “a subtle counternarrative that nuances an association of Kohn with a level of complete assimilation suggested by the melting-pot concept.” From Kohn’s elaborate paean to the idea of the melting pot, Pianko extracts two pieces of evidence that bolster this claim. The more important is Kohn’s citation of the Zionist Sir Alfred Zimmern’s account of how Americans, on the eve of World War I, “awoke to the strange reality that in spite of all the visible and invisible agencies of ‘assimilation,’ their country was not one nation but a congeries of nations such as the world has never seen before within the limits of a self-governing state.”

Pianko nevertheless maintains that Kohn remained a Zionist and that his later “formulations of Jewish nationalism are more closely linked to other counterstate theories of Zionism than it initially appears.” He supports this surprising assertion with a reference to Kohn’s 1957 book American Nationalism, which includes, he tells us in an unfortunate bit of dissertation-speak, “a subtle counternarrative that nuances an association of Kohn with a level of complete assimilation suggested by the melting-pot concept.” From Kohn’s elaborate paean to the idea of the melting pot, Pianko extracts two pieces of evidence that bolster this claim. The more important is Kohn’s citation of the Zionist Sir Alfred Zimmern’s account of how Americans, on the eve of World War I, “awoke to the strange reality that in spite of all the visible and invisible agencies of ‘assimilation,’ their country was not one nation but a congeries of nations such as the world has never seen before within the limits of a self-governing state.”

Congeries! The use of this word, Pianko tells us, would have reminded “anyone familiar with Zimmern’s writings on nationalism” of “his broader vision of creating commonwealths of federations of nationalities that would recognize collective groups and secure individual rights as the basis for international cooperation.” But so what? Could Kohn expect there to be more than a handful of such people in his mid-century American audience? And as Pianko himself admits, far from endorsing anything like Zimmern’s ideas, Kohn continues shortly afterwards to reject Horace Kallen’s related vision of America as a nation of nationalities.

Pianko’s effort to keep Kohn in the Jewish nationalist camp is no more convincing than his attempt to identify him as a surreptitious critic of the idea of the melting-pot. One of his principal pieces of evidence for his lasting loyalty to Zionism is an article that he published in Commentary in 1951 in which he praised the founder of cultural Zionism, Ahad Ha’am, as a man who “belongs in the age of nationalism to the small company of men of all tongues who in their unsparing search for truth and in the sobriety of their moral realism are the hope of the future.” But this comes at the end of an essay in which Kohn depicts Ahad Ha’am as a man whose philosophy was defeated by history, whose worst fears of the Zionist movement’s spiritual disintegration were realized after his death and who “might have felt today even lonelier among the Zionists than he did during his lifetime.” Kohn’s Commentary essay was really an obituary for Ahad Ha’am’s cultural Zionism.

Pianko ought to have left Kohn out of his book, which is primarily concerned with undoing some of the damage suffered by the Jewish people as a result of its having failed to travel along the routes demarcated by Rawidowicz and Kaplan. In his view, the success of state-seeking Zionism in establishing Israel has brought about a situation in which Jews “either constitute an ethnoreligious minority in liberal states” or “a sovereign nation within the Jewish state.” As a result of this split, Israelis’ Jewish identity is “intimately linked to a civic religion, to the Hebrew language and to patriotic defense of their homeland.” American Jews, however, are free to “decide to affiliate with a Jewish community as a religious minority group.” Consequently, “American Jewish and Israeli narratives of themselves and each other have actually contributed to increasing the rift between the two centers of Jewish life, thus retarding efforts to galvanize strong ties between diverse Jewish communities.” What the Jews of the world therefore need are new theories of Jewish peoplehood that “serve as an effective strategy for articulating the ties that bind the global Jewish community.” Pianko’s effort “to rehabilitate and revive . . . dissenting streams of Zionist thought that offer models of Jewish nationality as distinct from, and even defined in opposition to, the nation-state model” is designed to help them come up with such new theories.

Rose, Butler, Myers, and Pianko all have something in common, despite their differences. They are divided, of course, by their attitudes toward the State of Israel. The first two clearly wish that it had never come into being and can barely, if at all, stomach its existence. The latter two call attention to some of its defects and drawbacks, but only with a view to making it a better place. All four authors are united, however, in their critical stance toward political Zionism, which is what leads them to seek legitimation or guidance from those whom Pianko calls “counterstate” Zionist thinkers. Rose and Butler are too malevolent and ill-informed to merit serious consideration. Myers and Pianko, however, are learned historians and deeply committed Jews who write with their people’s best interests at heart and deserve our careful attention. Both of them have written books that make major contributions to our knowledge yet leave important questions hanging.

Myers has unearthed and celebrated the unpublished work of an obscure and lonely thinker whose ethical thought was, as he himself acknowledges, both lacking in solid foundations and rather unrealistic. He nevertheless believes that Rawidowicz’s writings can serve as a wake-up call reminding the supporters of the Jewish state of their moral duties. But why shouldn’t it inspire them instead, or just as much, to explain why, in the real world, absolute demands of the kind made by a thinker like Rawidowicz are inherently impractical, and therefore not morally compelling? Rawidowicz himself knew that the fulfillment of his dictates would “burden the state,” but denied that it would destroy it. Yet how could he be so sure? Did he really think that the worst hazards would be avoided if only Israel simply barred from return “those Arabs who have no desire or ability to be loyal citizens of the State of Israel” and admitted hundreds of thousands of others who were, perhaps, ready to do nothing more than pay lip service to the idea of a Jewish state until they re-established themselves within it? Maybe, in the end, he wasn’t so sure, and that’s why he chose to keep his radical proposal to himself.

Noam Pianko devotes several pages to Rawidowicz’s “Between Jew and Arab,” but he is by no means as concerned about the Jewish-Arab relationship as he is about the relationship between Israel and the diaspora. His own effort to dislocate the State of Israel from its central place in contemporary Jewish consciousness is not due to his disapproval of its policies but to his sense of what is necessary to revitalize both poles of the Jewish world. The Jews of the diaspora and Israeli Jews alike, he believes, need to acquire a new consciousness of themselves as equal members of a nation without borders. Familiarity with the thought of the dissident Zionists who long ago pointed to “the roads not taken” can help them reach this level of self-awareness.

But why should their forgotten ideas catch on today any better than they did when they were initially set forth? As Pianko reminds us, “counterstate” ideologies failed to win over the world’s Jews the first time around, and not by accident. Israelis reveled in their independence, and American Jews (the only contemporary Jewish community to which Pianko devotes any sustained attention) were pleased to have at their disposal a “nation-state logic” that made it easier for them “to assuage anxieties about dual loyalties” by affirming that they themselves were members not of the Jewish nation-state but the American one.

If things are different now, says Pianko, it is because “the correlation between nation and state has once again become increasingly blurry.” And “with the ascendancy of multiculturalism, ethnic identity, and criticism of cultural homogeneity, interest in rethinking the boundaries of groupness has grown dramatically.” Those Jewish intellectuals whom the zeitgeist has moved to reconsider their identities will find that Rawidowicz, Kaplan, and Kohn can help them to “think differently about difference.” From these three thinkers they can learn how to affirm “national solidarity as a primary allegiance for Jews, without relying on grounds of national inclusion, such as coercive criteria or ascriptive characteristics that might jeopardize liberal principles.”

Pianko has accurately characterized certain changes in the intellectual climate and pointed to specific circles in which a certain amount of rethinking Jewish identity is taking place. But these circles are small, as he himself acknowledges, and it is an exaggeration to say, as he does, that they are influential. Most diaspora Jews are infinitely remote from conceiving of themselves as members of a nation other than the one in whose midst they live. Most Israeli Jews have little interest at all in the Jews of the diaspora except insofar as they are potential immigrants to the Jewish state or capable of offering it material or moral support. Pianko’s call for a “program for global Jewish nationalism following the logic of Kaplan’s and Rawidowicz’s Zionism” is destined to fall on a multitude of deaf ears.

But our author’s case for rehabilitating and reviving the “counterstate” thinkers is not based primarily on their capacity to answer the felt needs of any existing group of people. His final and probably his strongest argument is that their way of thinking can help to counteract some of the deficiencies of the “sovereign mold, espoused both by American Jews and Israelis,” which have “hindered the development of a robust and global language for articulating global solidarity.” American Jews, Pianko argues, need to stop feeling that they are on the periphery of the Jewish world of which Israel is the center. “The self-negation of Jewish vitality outside the state has the potential to obfuscate the existence of innovative cultural production . . . Relying on a symbolic homeland disempowers local initiatives to galvanize sustainable models of communal affiliation. Moreover, it drains creative energy and financial resources that could invigorate local, self-sustaining cultural centers.”

Reliance on a symbolic homeland in which they do not live may indeed be something for which some Jews in the diaspora have paid a price in self-esteem and vitality. One ought not to forget, however, that most of the spring remaining in the step of the contemporary diaspora is the by-product of Zionism’s successes. Without the restoration of Jewish independence in the Land of Israel, it is hard to believe that the diaspora communities that survived the Holocaust would have been able to summon the energy to face the future, much less reshape it. Nor is it possible to imagine that today’s assimilation-ravaged branches of the diaspora would have the heart and the incentive to sustain themselves if Israel’s enemies were to succeed in wiping it off the map. A time like the present, therefore, when the State of Israel finds itself in the vortex of uncertainty and turmoil, does not seem like the best moment to rehabilitate time-worn theories of Jewish nationalism that could qualify or reduce its importance in the eyes of Jews who share a concern for its welfare. This is not to deny, however, that the problems to which Pianko points are real, and that a significant number of diaspora Jews feel somewhat estranged from a Jewish state that permanently relegates them to second-class membership in the Jewish people. If Pianko’s book alerts Zionists who are by no means “counterstate” to the dangers posed by this situation and motivates them to think creatively about them, it will have performed a useful service.

Suggested Reading

Why Is This Haggadah Different?

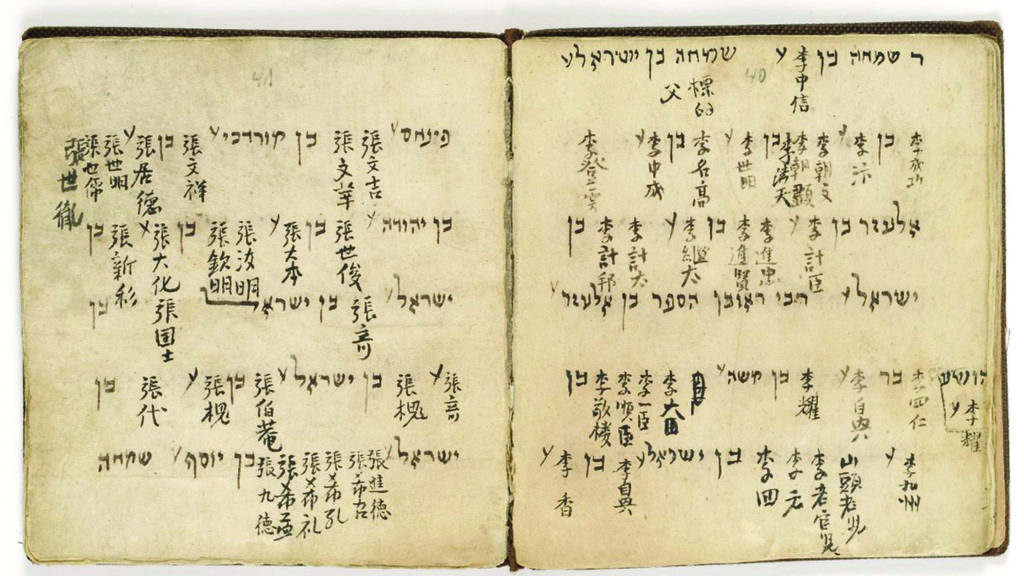

The Haggadah of China's Kaifeng Jews is not all that dissimilar from your Maxwell House version—but it speaks volumes about the community that produced it.

Letters, Fall 2022

Day School and State; An Apocryphal Footnote; Confirmed as Drowned, and more

Middle Position

An insider account reveals how personal relationships and rivalries often shape Washington's foreign policy.

The Israelization of Judaism and the Jews of France

The increasing importance of Israeli culture for diaspora Jews has yet to be fully grasped. Nowhere is this more true than in France.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In