Zion and Party Politics, 1944

During the three decades following Great Britain’s Balfour Declaration in 1917, American Zionists sustained a remarkably broad bipartisan coalition of support for their cause. Every president from Woodrow Wilson to Harry Truman endorsed the declaration’s pledge to facilitate the establishment of “a Jewish national home” in Palestine, as did the U.S. Congress, in a unanimous joint resolution, in 1922.

The summer of 1944, however, marked a crucial turning point. This was when support for Zionism was transformed from a low-risk political gesture to a bona fide election issue that would compel both Republicans and Democrats to compete for Jewish votes. This was also the moment when the Zionist cause faced its most severe political test, thanks to the actions of the president who enjoyed greater Jewish support than any of his predecessors or successors, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

During the 1930s, Roosevelt had periodically offered perfunctory expressions of sympathy for Jewish development of the Holy Land but said little else with respect to a subject that was seldom a matter of concern to U.S. policymakers. Shortly before the 1936 presidential election, however, at the request of American-Jewish leaders, Roosevelt discouraged the British government from implementing a planned closure of Palestine to Jewish immigration. But three years later, when the Jews’ situation was far more dire, Roosevelt refused Jewish leaders’ pleas to intervene against the MacDonald White Paper, which barred all but a trickle of Jewish immigrants from entry into Palestine.

Following America’s entry into World War II, Roosevelt’s attitude toward Zionism became even chillier; now he regarded talk of Jewish statehood as a distraction from the war effort. Even Rooevelt’s most ardent Jewish supporter, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, concluded that with regard to Palestine, Roosevelt was now “hopelessly and completely under the domination of the English Foreign Office [and] the Colonial Office.” Roosevelt rebuffed Chaim Weizmann’s personal plea, in July 1942, to mobilize a Jewish army to defend Palestine against a German invasion, fearing that such a move would antagonize the Egyptians. Roosevelt also rejected a request to permit the Palestine (Jewish) Symphony Orchestra to name one of its theaters the Roosevelt Amphitheatre, lest that small gesture be construed as a sign of too much support for Zionism.

By the autumn of 1943, there was growing concern among some prominent Democrats that the likely contenders for the 1944 Republican nomination, previous nominee Wendell Willkie and New York’s Governor Thomas Dewey, would make serious headway with Jewish voters in the next presidential election. Having won between 85 and 90 percent of the Jewish vote in 1936 and 1940, Roosevelt would seem to have had little reason for concern. But in October 1943, Vice President Henry Wallace noted in his diary “how vigorously Willkie is going to town for Palestine.” And Rabbi Wise confided to Roosevelt’s liaison to the Jewish community, David Niles, that he was “very much disturbed by the things that Dewey is saying about Palestine.”

Congressman Emanuel Celler, a Democrat of Brooklyn, was particularly concerned about Dewey. He was, after all, the popular governor of the state with by far the most electoral votes. New York’s 47 votes could be the key to the election, and the state’s large Jewish voting bloc—about 14 percent of New York’s electorate—could swing the state. In a memo to presidential secretary Marvin McIntyre, Celler warned:

The Jews in New York and other areas like Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, Sanfrancisco [sic], [and] Cleveland are greatly exercised over the failure of our Administration to condemn the MacDonald White Paper [. . .] It would not surprise me in the least to have Governor Dewey make a pronouncement in the not too distant future to the effect that Palestine cannot be liquidated as a homeland for the Jews and that the MacDonald White Paper must be abrogated [. . .] as far as the race of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob is concerned, [Dewey] would steal the show right from under our noses.

Around the time that Celler wrote his memo, Benzion Netanyahu, the father of Israel’s current prime minister, was thinking along much the same lines. An emissary in the United States of Revisionist Zionism, the militant wing of the Zionist movement founded by Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, Netanyahu had organized rallies and authored full-page newspaper advertisements that criticized the Allies for abandoning European Jewry and shutting off Palestine. But he also spent part of his time on Capitol Hill. “Most of the Jewish and Zionist leaders, led by Rabbi Stephen Wise,” he later reported, “were devoted Democrats and supporters of President Roosevelt. The idea of having friendly relationships with Republicans was almost inconceivable to them.” In the months prior to the June 1944 Republican National Convention, Netanyahu made the case for Zionism to GOP leaders, including former president Herbert Hoover; Senator Robert Taft, who was chairing the convention’s Resolutions Committee; and the influential Connecticut congresswoman Clare Boothe Luce. Netanyahu’s goal was to have the GOP platform include a plank supporting Jewish statehood in Palestine, which neither party had ever done before.

Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver had the same idea. Silver was Rabbi Wise’s co-chair and arch-rival at the American Zionist Emergency Council, the Zionist umbrella organization. Unlike Wise, Silver felt no special loyalty to Roosevelt and the Democrats. In fact, the Cleveland rabbi enjoyed a close relationship with Ohio’s Senator Taft. It was Taft who invited Silver to deliver the benediction at the 1944 GOP convention, which facilitated Silver’s efforts to persuade Republican leaders to include Palestine in the platform.

The parallel lobbying efforts by Netanyahu and Silver resulted in the GOP’s adoption of the plank they sought, and then some:

In order to give refuge to millions of distressed Jewish men, women and children driven from their homes by tyranny, we call for the opening of Palestine to their unrestricted immigration and land ownership, so that in accordance with the full intent and purpose of the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the Resolution of a Republican Congress in 1922, Palestine may be constituted as a free and democratic Commonwealth. We condemn the failure of the President to insist that the mandatory of Palestine carry out the provision of the Balfour Declaration and of the mandate while he pretends to support them.

Had the Republican plank referred only to Palestine and Jewish refugees, without mentioning Roosevelt, Rabbi Wise could not have objected. But the GOP’s criticism of Roosevelt—the president whom Wise revered as “the All Highest” and “the Great Man” in his private correspondence—was too much for him. Wise hurried to inform the president that he was “deeply ashamed” of the plank’s wording and issued a public statement criticizing the GOP for casting “an unjust aspersion” on Roosevelt.

What happened next would help shape the relationship between the United States, the Zionist movement, and the State of Israel for decades to follow. Rabbi Wise had not planned to attend the Democratic convention, which was scheduled for Chicago in July. But the Republicans’ embrace of Palestine changed matters. “I now think I shall go there,” he informed Supreme Court Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter, “in order to be certain that the Resolution on Palestine which must now be adopted shall more than neutralize the damage done by the Silver-inspired attack upon the Chief.”

Meanwhile, a delighted Rabbi Silver wrote to a colleague that “for the first time, our [Zionist] Movement finds itself in the fortunate position where both major political parties are competing for its approval.” He counseled Wise to use the GOP plank “as a lever to put through a similar and, if possible, a better plank in the Democratic platforms.” But at the same time, Silver cautioned his rival that anti-Zionists in the State Department “will bring pressure to bear . . . to have a watered-down, meaningless plank on Palestine” in the Democrats’ platform. Thus, Silver wrote to Wise, “You might have to go to the very top.”

As much as he resented Silver, Wise must have realized that, in this instance, he had a point. In the days preceding the Democratic convention, Wise repeatedly asked White House aides for a meeting with President Roosevelt to secure his “personal and administration support of [the] Zionist program” and affirmation of his desire to bring about “maximum rescue [of] Jewish civilians.” Wise’s request was denied. Roosevelt was inclined to duck the rabbi if Wise’s agenda included issues that the president preferred to evade.

Soon after arriving at the convention in Chicago, Wise was alarmed to find himself shut out of the deliberations over the resolutions. “It’s all so confusing and distressing,” he complained to a friend. “I can’t break through a cordon of bell boys.” In a note to President Roosevelt that went unanswered, Wise reported: “My information is that either no plank concerning Palestine is to be adopted or that the Platform will include a plank which is utterly inadequate.” Wise also heard through the grapevine that presidential adviser and speechwriter Samuel Rosenman—a Jewish opponent of Zionism—was pushing for a Palestine resolution so weak that it would constitute, as Wise put it, “a great gift to Tom D[ewey],” the Republican nominee. He did secure permission to address a public hearing before the Resolutions Committee—only to find that Rabbi Morris Lazaron, of the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism, had been granted equal time to testify against a Palestine plank.

But what Wise did in the hallways mattered more. Synagogue Council of America President Israel Goldstein, who joined him at the convention, later described how they positioned themselves near a revolving door directly downstairs from the room where the platform was being discussed, “so that every politician that came in would be bound to bump into Wise.”

He knew most of them by their first names [. . .] And he collared every one of these politicians and I was standing there at his side as a kind of junior assistant and the two of us together would indoctrinate that person in the two or three minutes that were available, and that person was on his way to the meeting of the Platform Committee which was upstairs.

Assistant Attorney General Norman Littell described in his diary the experience of being buttonholed by Wise. The rejection of his plank would “hurt the president,” Wise warned him. “It will lose the President 400,000 or 500,000 votes.” The Republicans had adopted “a satisfactory plank” on Palestine, he reminded Littell, and the Democrats needed to match it. Littell supported Wise’s efforts; so did Congressman Celler, who was a member of the Resolutions Committee and who was not shy about pointing to the possible electoral consequences of a Democratic retreat from Zionism.

Wise submitted to the committee a draft plank calling for Palestine’s “establishment as a free and democratic Jewish commonwealth.” The committee members, apparently responding to pressure from the State Department, watered down the wording to “the establishment there of a free and democratic Jewish commonwealth.” Unhappy Zionist officials interpreted the addition of “there” as “implying partition” (which the Zionist movement, at that point, opposed). Nor did the Democrats’ plank mention the plight of European Jewry. Still, the language on Palestine was as strong as the GOP’s, and its reference to a “Jewish” commonwealth arguably was more explicit than the language adopted by the Republicans. Wise could happily announce that “with the plank in both platforms the thing is lifted above partisanship.” Support for Zionism, and later Israel, would henceforth become a permanent part of American political culture.

Soon after the Democratic convention, Jewish leaders learned that Governor Dewey planned to issue a major pro-Zionist statement before election day. Wise and his AZEC colleagues then resolved to seek a public affirmation by President Roosevelt of his support for the Democrats’ Palestine plank. “There are things afoot which I do not like, designed to hurt you,” Wise wrote to the president, explaining why it was urgent to see him and Silver. “Nearly everything can be done to avoid them if we can talk to you and have from you a word which shall be your personal affirmation of the Palestine plank in the Chicago platform of the Party.” Roosevelt did not respond. Wise turned to Samuel Rosenman. “[I]t would be definitely helpful to THE cause if we could see the Chief with the least possible delay,” Wise implored him. “I would not press this as I do if I did not have reason to fear that fullest advantage might be taken of the Chief’s failure to speak on this at an early date.” Meanwhile, in Jerusalem, Wise’s close colleague Nahum Goldmann was briefing Jewish Agency leaders: “Wise will tell [Roosevelt] that this declaration could secure for him 200,000 additional votes in New York, and there is a chance that at the end of October the president will perhaps issue the declaration.” Finally, after three weeks of calls and cables, Roosevelt agreed to see Wise (but not Silver). Accounts by Wise’s aides indicate that the rabbi and the president discussed the role of Palestine in the election campaign and that Wise presented a draft of a message from Roosevelt that he wanted to have read aloud at an upcoming Zionist convention.

The day after Wise’s White House meeting, Governor Dewey announced his endorsement of the GOP’s Palestine plank. “I am for the reconstitution of Palestine as a free and democratic Jewish commonwealth in accordance with the Balfour Declaration of 1917,” the Republican nominee declared:

I have also stated to Dr. Silver that in order to give refuge to millions of distressed Jews driven from their homes by tyranny, I favor the opening of Palestine to their unlimited immigration and land ownership [. . .] The Republican Party has at all times been the traditional friend of this movement. As President I would use my best offices to have our Government, working together with Great Britain, achieve this great objective for a people that have suffered so much and deserve so much at the hands of mankind.

Hoping to counter the media attention Dewey’s announcement attracted, Roosevelt quickly approved the message Wise had proposed—but not before he had weakened Wise’s draft in four important ways. The original draft endorsed the goal of a Jewish commonwealth and added: “Ways and means of effectuating this policy must and will be settled as soon as practicable.” Roosevelt diluted this to a vague promise that “efforts” would be made “to find appropriate ways and means” of implementing the policy. The phrase “must and will be settled” was deleted entirely. The original draft referred to “an undivided Palestine”; in the final version, “undivided” was removed. The pledge to “do all in my power” was reduced to “I shall help to bring about.”

Roosevelt had the political leeway to water down the statement because Rabbi Wise, his loyal friend, would never divulge that he had done so. Consequently, the audience at the Zionist gathering at which the president’s message was read had no way of knowing his ambivalence regarding Palestine and Zionism. Nor did the Jewish voters who cast their ballots for Roosevelt the following month. Years later, one of Roosevelt’s most loyal Jewish supporters, his ethnic affairs liaison David Niles, would remark, “There are serious doubts in my mind that Israel would have come into being if Roosevelt had lived.” The events of 1944 help explain these doubts.

Suggested Reading

High Threshold

Visitors to the Hazon Ish's house would sometimes enter through the window; the venerable sage occasionally left home the same way. “A window,” the Hazon Ish reassuringly explained, “is in fact just a door with a high threshold.”

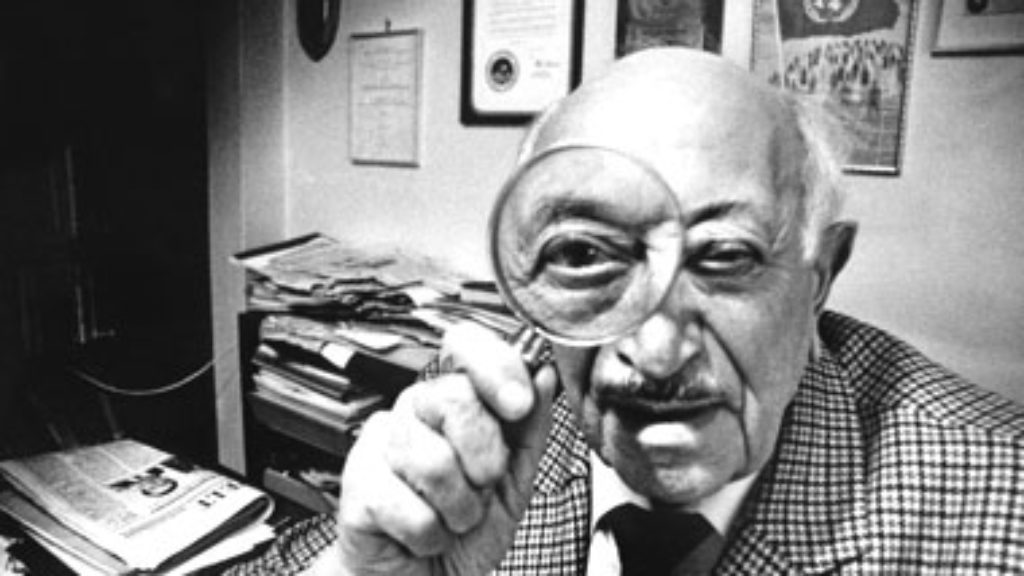

Simon Wiesenthal and the Ethics of History

Was Simon Wiesenthal an intrepid hunter of mass murderers? Or was he in fact more of a charlatan than a hero? Tom Segev's new biography of the most successful—and controversial—Nazi-hunter raises more questions than it cares to answer.

Jonah: The Sequels

“And shall I not care about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than one hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not yet know their right hand from their left, and many beasts as well?”

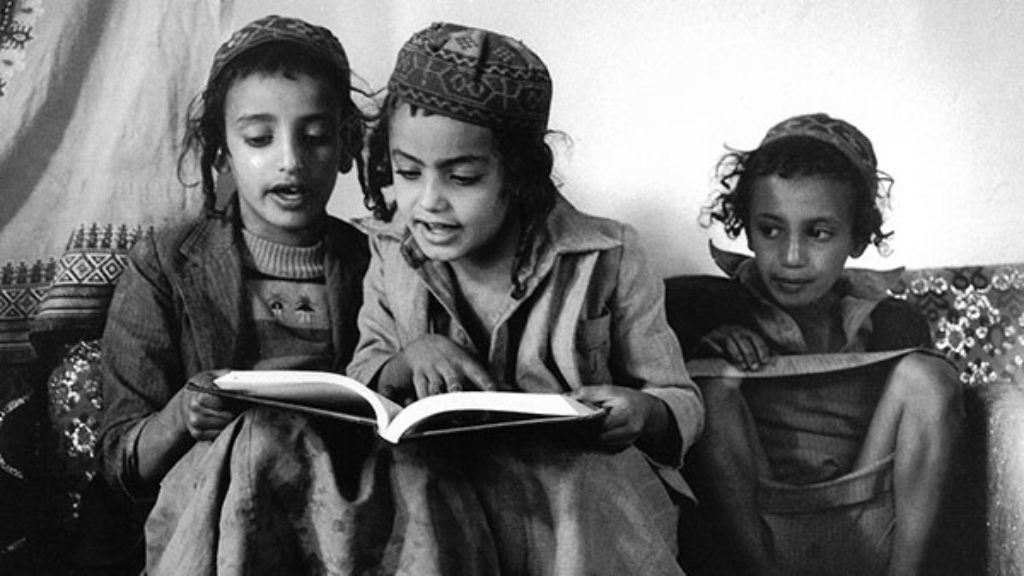

Visiting Yemen in the 1980s: A Photo Essay

"Sometimes one really does find that moment and the image seems to capture a person—this particular Jew, this particular way of life—but often one does not and feels the need to return, to try again." But in this case, there are no Jewish communities in Yemen to return to.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In