Three Portraits of Jewish Excellence—at 29

A few years ago, I spoke to a group of young men and women who were embarking on professional lives devoted, in one way or another, to Judaism and the Jewish people. It was a daunting task. Shuffling through their impressive CVs, I did a little math and found that their average age was 29. I began to wonder: What were some of the great Jewish figures of the last century doing at that age? In keeping with the various aspirations of the group—which were political, philosophical, and religious—I chose David Ben-Gurion, Leo Strauss, and Joseph Soloveitchik.

Of course, these were not the only plausible choices, but they were certainly among the towering figures of modern Jewry. Their achievements still reverberate far beyond the relatively small playing grounds of Palestine, or the Academy for the Science of Judaism, or Yeshiva University. And yet before they were great men, they were young men, finding their way, seeking and failing, and eventually embracing different visions of what Judaism demands of us. If these three Jews sat together in a seminar room, they would surely disagree on many things, including the most ultimate things. But they all led lives worthy of admiration. They all led lives of Jewish consequence. And my hope was that the young Jews in the audience might learn something meaningful from an encounter with Jewish excellence in the making.

The man who became Ben-Gurion was a Zionist from the beginning, as Michael Bar-Zohar recounts in the opening lines of his biography:

David was barely eleven, a pale Jewish boy wearing a long black gown in the Plonsk synagogue, when he first heard that the Messiah had arrived. He was a handsome man, they said, with proud, burning eyes and a black beard. His name was Theodor Herzl, and he would lead the people of Israel back to the land of their forefathers. With the innocence of childhood, David believed the story and instantly became a fervent follower of the Zionism which was sweeping the Jewish world. The seeds of that Zionist faith had already been sown on his early childhood, when he sat on his grandfather’s knee and learned the Hebrew language, word by word, from Zvi Aryeh Gruen; when he listened to his father, Avigdor Gruen, one of the local leaders of the Hovevei Zion (“Lovers of Zion”), a forerunner of the nascent Zionist movement. While still a child, David Gruen decided that one day he would make his home in the Land of Israel.

The young David Gruen joined his father in the activities of Hovevei Zion. Later, he recalled reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which inspired him “with a sense of horror at slavery, subjugation, and dependency.” At age 14, he helped found the Ezra Society, which encouraged the young Jewish boys of Plonsk to speak with pride the Hebrew language that was their true birthright.

In what has to be one of the great unanswered letters of modern Jewish history, David’s father wrote the following lines to Theodor Herzl in 1901:

Leader of our people, spokesman of the nation, Dr Herzl, who stands before kings! I have resolved that I shall pour out my heart to his highness . . . [Though I am] the youngest of the thousands of Israel, God has blessed me with a superior son, diligent in his studies. Still in the prime of his youthful years, about fifteen, his belly is [already] filled with learning, and in addition to our tongue, the Hebrew language, he also knows the language of the state, the lore of mathematics, and more, and his soul yearns for study. But every school is sealed before him, for he is a Jew. I have resolved to send him abroad, to study science, and several people have advised me to send him to Vienna, where there is also a center for Jewish learning, a college for rabbis. Thus I have resolved to bring this account before my lord, that he may commend my son and [also that I may] enjoy the benefit of my lord’s advice and sagacity. For who is a mentor like unto him, and who, if not he, can advise me what to do? For I am powerless to maintain my son, whom I love like the apple of my eye.

So how did this young Zionist, apple of his father’s eye, end up in New York on May 16, 1915, just a few months before his 29th birthday? By way of Palestine, where he spent his late teens and early twenties working the land (“Hebrew labor on Hebrew soil,” was his motto); then Jerusalem, where he became a young editor of Ahdut, the official journal of the Poalei Zion; then Salonica, where he went to study law, believing that the new Jewish homeland would emerge as part of the Ottoman empire. Along the way, he suffered various illnesses; he mastered many languages; and he read history, philosophy, and literature like a madman. Just as World War I broke out, he returned to Palestine on a “ramshackle Russian vessel” that was chased by two German warships, only to discover what his biographer describes as “a scene of despair and disintegration,” with “the whole settlement project . . . in danger of destruction.” He was soon deported from Palestine by the Turks, whom he still believed would eventually resume control of the land and under whose authority he believed he would soon return.

Shortly after his arrival in the United States, Ben-Gurion began his first tour through North America, trying to recruit a new wave of American Jewish pioneers—a “labor army”—to replenish and strengthen the Jewish communities of Palestine. This was, one might say, the future political founder of the Jewish State’s first real political campaign—on the road, going from city to city, in search of followers. He did not find many.

Many of the branches of Poalei Zion elected not to invite him at all, more interested in speakers who could reminisce in Yiddish about life in the Old Country and thus help raise funds for their local work rather than trying to recruit away idealists to Palestine. In the cities he visited on his first tour—Buffalo, Detroit, Toronto, Montreal—he spoke to mostly empty rooms and managed to sign up only a few volunteers. The trip was a failure, and it showed how little Ben-Gurion understood the situation and sensibilities of the American Jews he was aiming to enlist.

In September 1915, Poalei Zion held its convention in Cleveland, where Ben-Gurion gave a long address setting forth his views:

We shall receive our land not from a peace conference . . . but from the Jewish workers who shall come to strike roots in the country, revive it, and live in it. The Land of Israel shall be ours when a majority of its workers and guardsmen shall be of our people.

The Cleveland speech was successful enough that Ben-Gurion was sent out on a second North American tour. And while he still often spoke to half-empty rooms, there were flashes of a political force of nature in the making: in Minneapolis, where Ben-Gurion single-handedly beat back a faction of Bund sympathizers. In Galveston, Texas, where “an anti-Zionist took the floor and alleged that Palestine was a country full of graves, beggars, and idlers. Ben-Gurion exploded, and the audience almost came to blows. He managed, however, to gain control of the two hundred Jews present and win them over to his side.” And finally, on his last stop in Milwaukee, where he met a young woman named Goldie Mabovitch, who later became Golda Meir. On March 24, 1916, the 29-year-old Ben-Gurion returned to New York.

While Ben-Gurion was on the road, the party was organizing the publication of a book in Yiddish, to be called Yizkor, “in memory of the works and watchmen in Palestine who had given their lives in the service of Hashomer, the Jewish defense organization.” Ben-Gurion’s contribution to the book, entitled “Selected Reminiscences—From Petah Tikva to Sejera,” was a moving tribute to his comrades. It is also a revealing picture of how the young, pioneering, love-struck David Gruen transformed into the still idealistic but reality-chastened David Ben-Gurion. The essay opens with his arrival in Jaffa as a member of the Second Aliyah (1904–1914), and then his immediate departure to the colony of Petah Tikvah:

We were all lively, bold, and unspoiled, full of enthusiasm, carefree and full of joy. We felt rejuvenated, reborn, having left the small dirty alleyways far, far behind us to live among gardens and orchards. Here everything was different—nature, life, and work, even the trees. . . . No more books and squeezing the benches and empty mental gymnastics—we work. We not only work, we conquer—the soil, life.

Ben-Gurion eventually left for Sejera (now Ilaniya), in the Galilee. “Here,” he wrote, “I felt the Land of Israel.” He continued:

But here, too, the ideal was blemished because though the workers were all Jews, the watchmen were not. You didn’t notice this in Judea, where things were quiet, but the Galilee was more dangerous, filled with envious and armed Arab neighbors. In these circumstances security depended entirely on our watchmen, and yet were we to behave here as we had in our exile [goles], hiring others to protect us and our property? We approached the administration and the Jewish farmers and tried to sell them on the principle of Jewish self-defense, but they rejected it as impractical and dangerous. “The dismissed Arab watchmen would not keep silent, but will attack and rob us. . . . We are few and weak, surrounded by strangers and enemies. Under these conditions, is it possible to arrest anyone?” But we demanded our national dignity, the honor of our ideal. Was our life and our honor to depend on others here as well?

The concluding section of Ben-Gurion’s essay—the most powerful and the most political—describes the events of Passover 1909. “Sejera, first to institute a Jewish watch, was also the first to experience its casualties.” Tensions had risen all of the previous year over border disputes between the Jewish colony and the neighboring Arab village. The communal Seder was interrupted by a young man who reported having been attacked on his way. He and his companions had shot and killed one of their Arab attackers, who died the following day in the hospital in Nazareth. The expected repercussions were not long in coming.

Ben-Gurion was chairing a session of a Labor Zionist conference that was taking place during the weekdays of the festival when reports came of attacks on the settlement’s herds and sabotage of the fields. The Jews fought back, leading to a bloody confrontation in which two members of Sejera were fatally wounded. As Ben-Gurion remembers:

In the large hall, where we had conducted the Seder, the two men were laid out in sheets. There they spent the night. The next day we did not go to work. We had to dig a large grave for the two victims, for our two comrades. Silently we carried them on our shoulders from the hall to the Sejera cemetery and there, without eulogies, we laid them together in the grave. . . . Together they had lived in Sejera, in the Jewish village, with a single hope working for a single goal, and together they fell. So they will rest forever. One was a watchman, the other a colonist, both in Eretz Israel—precious and hallowed.

The book in which this essay appeared was a success, and Ben-Gurion’s essay quickly made him a celebrity within the movement that just a few months earlier had mostly ignored him. And so it was, just a year later, that the empty halls of Buffalo were replaced by the Great Hall at Cooper Union, where Ben-Gurion addressed two thousand people at a November 29, 1917 conference celebrating the Balfour Declaration. There, he won passage of the following resolution, which he had personally drafted: “We solemnly pledge to follow in the path and continue the work of our courageous pioneers, workers, and watchmen who gave their lives for the freedom and revival of the Jewish people in the Jewish land.” It was a pledge he would indeed fulfill.

In the mid-to-late 1920s, when Ben-Gurion was a Zionist leader on the rise, building the Histadrut and helping to found Mapai, a twenty-something intellectual named Leo Strauss was living in Germany, as he would later famously recall, “in the grip of the theological-political predicament.” Strauss grew up in rural Germany in a religiously observant, if not theologically sophisticated, home—“sing[ing] [the zemirot] as a child in utter ignorance of their ‘background,’” as he later remembered in a letter to Gershom Scholem.

The young Strauss was given a classical German humanist education. As he recalled:

Furtively I read Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. When I was sixteen and we read [the Platonic dialogue] Laches in school, I formed the plan, or the wish, to spend my life reading Plato and breeding rabbits while earning my livelihood as a rural postmaster. Without being aware of it, I had moved rather far away from my Jewish home, without any rebellion. When I was seventeen, I was converted to Zionism—to simple, straightforward political Zionism.

In those early years, Strauss was especially drawn to the Revisionist Zionism of Jabotinsky, not the Labor Zionism of Ben-Gurion. He was involved in Zionist youth groups and wrote for various Zionist publications. Zionism was his political passion. But as he entered his twenties, Strauss’s Zionism was also the occasion for reflection on the theological-political predicament—first and foremost, as a Jewish problem, and increasingly, as a way of seeing the human problem in its modern face. What began as a search for “a Jewish center of gravity,” in thought and in politics, led Strauss to a full-scale reconsideration of the divide between philosophy and faith, belief and unbelief, Jerusalem and Athens—and, as it originally appeared to him then, the stark choice between orthodoxy and atheism.

So what was Strauss’s theological-political predicament? In Weimar Germany, at the supposed height of Jewish emancipation within German society and the assimilation of Jews to German culture, Strauss observed two problems: the continued force of anti-Jewish discrimination and the fact that assimilation seemed to require a Jewish betrayal of the Jewish past. For both these reasons, the most spirited young Jews—Jews who rejected the passive submission of orthodoxy and balked at the indignity of assimilation—turned to political Zionism as a superior answer to the Jewish problem. They sought the re-founding of the Jewish nation, and they aimed to restore Jewish pride.

But it was here that Strauss discovered the second layer of his theological-political problem—the fact that political Zionism was empty without a Zionist culture and that the only true Zionist culture—a culture that was authentically rooted in the true story of the Jewish people—was traditional Judaism. This realization led Strauss to ask a series of radical questions: Is orthodoxy, in fact, the only real answer to the Jewish problem, and is it still plausible or desirable in the modern age? Is political Zionism doomed to failure because it has no deeper roots in the divine call of the Jews? In a 1928 essay provoked by Sigmund Freud’s recently published work The Future of an Illusion, the 29-year-old Leo Strauss lays this all out with great clarity and tremendous urgency:

Given the inadequacy of Herzl’s Zionism, which expressed itself most clearly in his Old-New Land, cultural Zionism had an easy position to defend. There was something convincing in the consideration that whoever affirms the Jewish people necessarily affirms its spirit, and therefore necessarily affirms the culture in which its spirit revealed itself. From the affirmation of national culture some proceeded to the affirmation of the national tradition of the Law; among these were certainly a few who did not fully realize that this law claims to be divine law. The believers cleared the way from their side. How often have we heard that what Judaism calls for is not belief but action, namely, the fulfillment of the Law. But what the believer praises as a hearkening and a believing that arises from doing is to the unbeliever a slippery slope into belief, a numbing of conscience, and self-deception. No one can believe in God for the sake of his nation; no one can fulfill the law for national reasons. It is bad enough that even today one must still waste words on the thoughtlessness that follows this path. But can one remain standing at the affirmation of national culture? Cultural Zionism leads up to the question that is posed by and through the Law, and then it capitulates, yielding either to resolute belief or to resolute unbelief. … This struggle is ancient; it is “the eternal and sole theme of the entire history of the world and of man.”

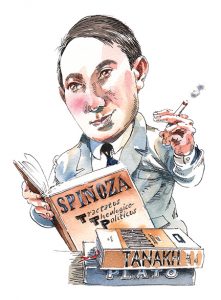

Could the stakes be any higher? Strauss’s main focus during his late twenties, from the years 1925 to 1928, was a book-length study of Spinoza’s critique of religion, as it was crystallized in his Theological-Political Treatise. He was a young fellow of the Academy for the Science of Judaism, which expected him to write a conventional, value-free scholarly study of Spinoza as a biblical critic. This is not the book Strauss would write, much to the chagrin of his main patron, the historian of philosophy Julius Guttmann. Strauss sought, instead, to try to recover the original plain of battle between philosophy and revelation, belief and unbelief.

Provoked into the depths of thought by the combination of his political predicament and intellectual temperament, Strauss had discovered the terms of his mature philosophical life: to think in the tradition of Athens while being continually haunted by the claims of Jerusalem. The 29-year-old author of Spinoza’s Critique of Religion argued that Spinoza had not in fact disproven orthodoxy at all, since the pious believer appeals to a source of authority, grounded in revelation, that reason has no right to judge, and to a set of beliefs about the divine creation of the world and the human need for redemption that reason cannot refute. Moreover, the enlightenment of Spinoza and his successors rested on a foundational premise—man’s capacity to guide his own life by the light of human reason alone—that was itself highly questionable. It rested on a faith in man’s capacity to conquer nature through science, a faith that seemed likely to achieve proximate successes but ultimate failure. All this led Strauss to wonder whether or not the new atheism—Nietzsche’s atheism—perhaps showed us the world as it really was. In that same 1928 essay on Freud, he wrote:

Long ago it was decided that the terribleness of belief is not an objection to belief; now unbelief has also matured enough to arrive at the insight that the probably desperate situation into which man has been brought by unbelief in no way justifies belief. Much is gained when the despair, the hopelessness, the helplessness of man, when “the misery of man without God,” when the restlessness, the lack of peace, the staleness and shallowness of life without God are no longer an objection to unbelief; when it no longer seems impossible that truth and depth are opposites, that only illusion has meaning.

But Strauss did not accept that the only choice, the ultimate choice, was between biblical orthodoxy and modern atheism. He looked instead to ancient and medieval philosophy as a way to recover a more human search for the best way of life—a quest that began, as philosophy always begins, from reflection upon one’s particular condition. As Strauss himself put it a few years later in his first important work on Maimonides:

The situation thus formed, the present situation appears to be insoluble for the Jew who cannot be orthodox and who must consider purely political Zionism, the only “solution to the Jewish problem” possible on the basis of atheism, as a resolution that is indeed highly honorable but not, in earnest and in the long run, adequate. The situation not only appears insoluble but actually is so, as long as one clings to modern premises.

The 17-year-old Zionist had become a 30-year-old Athenian—yet always respectful of the claims of Jewish law that he himself could not bring himself to obey, forever awed by the claims of revelation that he himself could not accept, and deeply aware that, in choosing his path, he still could not transcend the terrors and responsibilities of Jewish history.

If Strauss was a philosophic “Jew who cannot be orthodox,” can one speak of a philosophic Jew who must be orthodox? The young Joseph Soloveitchik was heir to a great rabbinic family, and already such a master of the talmudic tradition that his grandfather would supposedly rise when the teen-aged Soloveitchik entered the room. And yet, even at this young age, he already seemed to have philosophical questions and doubts that led him to doctoral studies in 1920s Berlin. In Between Berlin and Slobodka, a fascinating account of the intellectual journeys of six modern Jewish figures, Hillel Goldberg introduces Soloveitchik as follows:

Born in 1903 to Rabbi Moses Soloveitchik, Joseph Baer Soloveitchik . . . grew to manhood in a household whose supreme value was intellection and in which secular studies were, on the surface, both superfluous and anathema. For twelve years his father educated him rigorously in the critico-conceptual talmudic method of his grandfather, but his mother . . . surreptitiously introduced her son to Hebrew, Russian, and Scandinavian literature. Primarily at the urging of his mother he received a secular education in his latter teens under private tutors and then, when he was 22, enrolled in the University of Berlin—a transition that, because of his unusual talmudic talent, reverberated as a shock and betrayal in most of the Soloveitchik side of the family.

As Goldberg recounts, Soloveitchik was one of “a cluster of young intellectuals”—including Abraham Joshua Heschel, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, and Isaac Hutner—who converged in Berlin at the time and who struggled to define the relationship between “a discrete and complex religious tradition, proudly affirmed” and the ideas of modern, Western thought. “Not even Philo of Alexandria or Maimonides and Judah ha-Levi . . . had embodied so sudden and drastic a shift from an indigenous, affectively as well as religiously enveloping Orthodoxy to the heart of Gentile culture, as did these iconoclasts. Save Abraham Joshua Heschel, Rabbi Soloveitchik remained in Berlin longer than any of them.”

Soloveitchik’s decision to go to Berlin has remained mired in controversy within the Orthodox world, a controversy that mirrors the larger debate within that community about the worth of so-called “secular knowledge.” Rav Soloveitchik still awaits his great biographer, but to make at least provisional sense of those years, and what they have to do with the thinker and teacher that Soloveitchik would become, two questions seem central: Why did he write an incredibly difficult, highly technical, philosophically abstract dissertation on Hermann Cohen’s neo-Kantian epistemology? And who was Rabbi Hayyim Heller?

I leave it to the professionals to fully characterize Soloveitchik’s critique of Hermann Cohen, but at least part of the difference between them lies in how they understand what we experience in the world as actuality, as what is real, as what is lived. According to Soloveitchik, thought does not generate being, since being is the “original datum” for thought and thus transcends thought. For those who want the real thing—it has never been translated into English, by the way—here is a little taste of the 29-year-old’s dissertation:

That Being reaches only to the objects of judgment is, according to the consequent-idealistic conception, self-evident, but that does not justify us in equating the two concepts. The specific character of the object of judgment certainly exists in its posited reality but in order to form such an object the validity of the category of being must already be presupposed. Otherwise we would miss the unique and characteristic aspects of the object of judgment. The complete spiritual functions, not merely the cognitive judgments, are intentional acts, which are directed to the objects. Feeling and willing point to affective and volitional objects. Emotional thinking as an intentional act takes an objective form. That which is unique in the object of judgment insists on its full title to being. Being must count, therefore, as an original datum of thought, which first grounds the object of judgment and lends it dignity. In order to ground Being, the postulate of a transcendent component is unavoidable.

One way to interpret this phase of Soloveitchik’s life and thought is to treat his doctoral work as a purely technical dissertation that might as well have been in mathematical physics—a branch of secular learning walled off from the heart of Jewish theological and moral teachings. This seems to me misguided, though some in the Orthodox world make this move, when they aren’t busy pretending that Soloveitchik only went to Berlin to avoid the Polish military draft. The other way is to treat the dissertation as Soloveitchik’s effort to clear the philosophical brush—to write an “epistemological prologue,” as the scholar Reinier Munk described it—so that he might go on to articulate a new philosophy of mind and man out of the sources of halakha that could hold its ground in the modern world.

And this, it seems to me, is the heart of the connection between the Berlin dissertation of the 29-year-old Soloveitchik and the more mature works—The Halakhic Mind and Halakhic Man—that he would complete in the mid-1940s: In his view, there is a unified phenomenon of being, in which subjective experience and objective reality become one. This unity of being is embodied in its highest form in the halakha, as a way of life that is lived and an order of reality that is both given and made, revealed and fashioned, through the apprehending-and-creating work of the halakhic mind. As Soloveitchik would later write:

No worshipper has ever isolated the idea of God from the concrete world, and placed it in some immaculate transcendental sphere. The religious experience is a composite phenomenon involving not only God but the ego and the sensuous environment of the homo religiosus. He seeks direct contact and close companionship with God and perceives Him not in a transcendent glory, alien and sometimes hostile to the world, but in His full proximity and immanence. He views God from the aspect of His creation; and the first response to such an idea is a purified desire to penetrate the mystery of phenomenal reality. The cognition of this world is of the innermost essence of the religious experience.

As he boldly declares in the last sentence of this work, The Halakhic Mind, “out of the sources of halakha, a new world view awaits formulation.”

While we know relatively little about Soloveitchik’s life and routine during his years in Berlin, we do know that he continued to “learn” in the traditional Jewish sense of the word and that, in this, he found his guide in Rabbi Hayyim Heller. Heller was himself both a master talmudist of the Lithuanian school (like Soloveitchik he had been acclaimed as an illui, a prodigy) and a modern historical scholar. To see Rabbi Heller as Soloveitchik saw him is to understand the very nature of piety and tradition as Soloveitchik aspired to them. This world view is captured movingly in Soloveitchik’s eulogy of Heller, who ended up teaching alongside Soloveitchik in the Rabbi Isaac Elachanan Theological Seminary of Yeshiva University and died in New York, at the age of 80, in 1960. It not only beautifully evokes the spirit of the man who so influenced Soloveitchik in those Berlin years, it captures the way of being in the world that Soloveitchik would devote his life to defending.

When the [God-seeking] few must struggle against the [spiritually impoverished] many, the need to draw courage from the living tradition as it is reified in a real personality attired in the majesty of time—a mediation, a bridge between fathers and sons, between strength and weakness—becomes much greater. Under such conditions, the trembling, wrinkled hand-shake with its rhythm of generations; the fatherly or motherly glance in which abides the mystery of the past; the strains of a tremulous voice, in which is preserved the silence of Eternity; tales of strange and wondrous persons, of events wrapped in the mist of passing time—these can turn the balance in favor of the holy against the profane. . . . Only such a man, a prophet of God, a vestige of an ancient era, a remnant of the scribes of the past, could fortify weak knees and revive the hearts of the despondent.

Rav Hayyim [was such a man], a remnant of the scribes. A spark from the soul of Ahiya ha-Shiloni, who had clung to Moses as a child, sank into his soul. As long as Rav Hayyim was with us, among us, there existed a strong tie between us and earlier generations. When he went away, the knot was undone. . . . When I visited him at home, on the West Side of Manhattan, with its congeries of bustling, hollow, Jewish life; with its synagogues, societies, clubs, and their auxiliaries, I always felt as if I were entering another world, as if I had breached some border separating two realms of being—the domain of earlier generations, of Shakh, Taz, and Gra, and that of modern Orthodoxy, with its snipped wings and rootlessness, unable to fathom the depths of religious experience. . . . Moved by old, forgotten tales, he chuckled and sorrowed with his heroes. Images he described came to life, pushed their way into his modest room. Do you know where this power came from? Not from any art of speech or imagery! He never used a metaphor. He lived the events he recounted. He himself belonged to those generations, whose greatness he transmitted to us. . . . O he was a remnant of the ancient scribes.

What he said in Heller’s name we can now say of Soloveitchik—“my eyes are to God and His Shekhina; I will not cease seeking; otherwise my life is frenzied and tempest-tossed. The distance enchants, captures my heart, dragging me onward, onward.” Such is the soul of the lonely man of faith, homo religiosus.

There is, of course, much more to say about Ben-Gurion, Strauss, and Soloveitchik, both individually and in comparison with one another. Each of them was a deep and original reader of the Hebrew Bible; each of them grappled with modern philosophy; and each of them experienced early successes as well as early failures—be it Ben-Gurion in the empty halls of Buffalo, or Strauss when his Spinoza book was censored and delayed by his unhappy patrons, or Soloveitchik when he was offered and then refused a position in Jewish theology in Chicago. Yet to really understand the Jewish spirits of these men—and the differing marks they left on Jewish history—one should see them in the biblical light in which they saw themselves. And so permit me to conclude with a brief sermon, a drasha.

Although rabbinic tradition imagines him as much older, it is not implausible to think of Moses as a young man when he encountered the burning bush, if not precisely 29, not far from it. Seeing the bush aflame yet unconsumed, Moses does what philosophers and scientists have always done: He asks a question and seeks by his own powers to find an answer. “I must turn aside to look at this marvelous sight; why doesn’t the bush burn up?” This is Spinoza’s Moses, who treats God’s call as an invitation to thought. But the story, of course, does not end there. The second Moses in this short passage is the Moses who “hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God.” In his piety, he lies prostrate before the Almighty, creator of all, whose ways are not his ways and whose powers he cannot fully fathom but to which he knows he must submit. This is Soloveitchik’s homo religiosus par excellence.

The final Moses is Moses the liberator, a politicial leader in the best and highest sense of the word, who comes to see the suffering of his people not as a reason to ask, or a reason to submit, but as a commandment to act. “Come, therefore, I will send you to Pharaoh, and you shall free My people, the Israelites, from Egypt.” So God demands, and eventually Moses accepts the responsibility of leading his nation.

We can admire—and we should—Ben-Gurion’s statesmanship, Strauss’s wisdom, and Soloveitchik’s piety. But perhaps only Moses—the greatest Israelite of all—knew all three facets of Jewish excellence from the inside, and so he remains the enduring exemplar for Jewish leaders of every age, on whose shoulders and ours the Jewish story continues.

Suggested Reading

“Whoever Is Hungry, Come and Eat”? From the Babylonian Poor to the Ashkenazi Elijah

Why do we begin the seder by inviting “whoever is hungry” to come and eat? Aren’t the guests already at the table? And why do we do it in Aramaic? It has something to do with Babylonian magic bowls . . .

Hardware, Software—or Love?

Maimonides’s Abraham was a natural philosopher who discovered God through reason, but the biblical Abraham did nothing at all to earn God’s election.

Remembering Philip Roth

Michael Kimmage's review of Philip Roth's final novel, Nemesis.

Old-New Debate

Theodor Herzl is indisputably Israel’s principal Founding Father. He was not the first person in modern times to call for the creation of a Jewish state, but he summoned into existence the movement that made it possible and marked out the path that it was to pursue. When he first published The Jewish State in 1896, the proto-Zionist groups in…

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In