The Language of Babylon

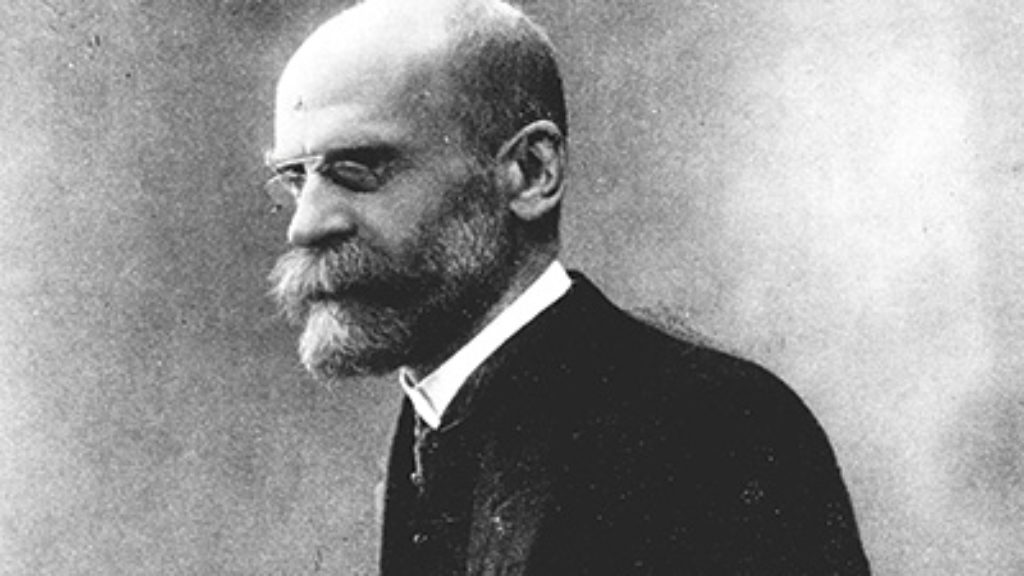

Life After Baghdad: Memoirs of an Arab-Jew in Israel, 1950-2000 is the newly translated volume of memoirs by the Iraqi-born Israeli scholar of Arab literature Sasson Somekh. It is not nearly as beguiling as its predecessor, Baghdad, Yesterday: The Making of an Arab Jew, which appeared in 2007 in one of the handsome little Gallimard—inspired paperbacks put out by the Jerusalem—based Ibis Editions press. Nevertheless, it is welcome, not only for continuing Somekh’s story, but for adding another book to the shelf of those produced by the last generation of Jews to have been born and raised in Iraq.

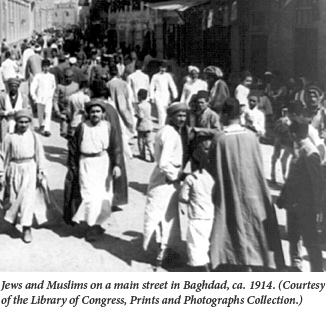

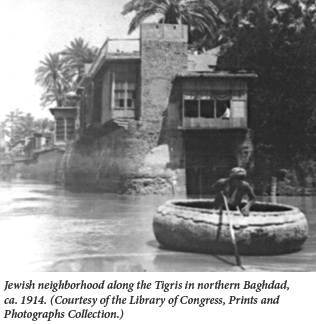

The Jewish presence in what is today Iraq dates back to the 6th century B.C.E. and stretches through the Middle Ages to modern times. After Baghdad became the seat of the Islamic Caliphate in the 8th century, it developed into the political and spiritual capital of the Jewish world, and its rabbis, intellectuals, merchants, and officials shaped what Judaism would be for centuries afterwards. Jews continued to occupy an important place in the city right up into the modern period. The census in 1917 reported that Baghdad’s total population of 200,000 was forty percent Jewish, a larger proportion of the total than in Warsaw, Odessa, Vilna, or any of the famous Jewish centers of Europe. When the British took over the region from the Ottomans after World War I and created the state of Iraq, Jews, already receptive to educational and cultural influences from Europe, were at the vanguard of the heady transformations of an imported modernity that included streetcars, cinema, education for women, and a liberalizing monarchy under the British-installed Faisal I.

Under the new regime, many Jews moved into the middle classes, and some became prominent in finance, banking, and trade. Others contributed to the arts and to modern Arabic literature, poetry, and drama. In the 1920s, a Jew served as the country’s minister of finance. Jews wrote the first Iraqi short stories in Arabic, and they produced some of the best-known singers and musicians in Iraq, indeed in the whole of the Arab world.

Anti-Jewish persecution, stoked by Arab and Palestinian nationalism, anti-British sentiment, and the example of Nazi Germany, became a notable part of the Iraqi landscape beginning in the 1930s. After the virulently anti-Semitic pro-Nazi leader of the Palestinian Arabs, Hajj Ammin al-Husseini, was kicked out of Palestine by the British in 1937, he took up residence in Baghdad, where he helped to foment anti-Jewish agitation. The Farhud, a pogrom in which scores of Baghdadi Jews were murdered, took place in 1941. The younger generation of Jews, who had usually been liberal and integrationist in their politics, increasingly turned to communism or Zionism as solutions to their untenable position in Iraqi society. Finally, in the wake of the creation of Israel in 1948, violent Arab nationalism resulted in the flight of the Jewish populations of many Middle Eastern countries, Iraq included.

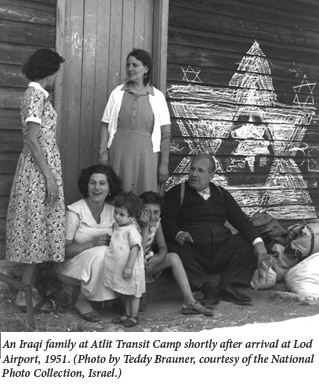

When the government allowed the Jews to emigrate in the early 1950s, more than ninety percent of the 120,000 Jews of Iraq left their country, most resettling in Israel. Their property and assets were frozen and seized by the government, reducing thousands to sudden poverty despite their mostly middle-class backgrounds. Many of them joined other new immigrants in the squalid transit camps that were Israel’s response to the massive influx of new citizens, where they suffered injuries and insults that contributed to festering ethnic resentment for years afterwards. The tiny community that remained in Baghdad, meanwhile, became the scapegoat of the Ba’ath regime, which in the late 1960s forced Jews into show trials and hanged many of them in the public square of Baghdad, where hundreds of thousands came to gawk at the corpses of these alleged traitors.

More than sixty years after its first vanishing, Jewish Baghdad is now undergoing a kind of second death, as the last generation of Jews who were born and grew up in that city is aging and dying. Somekh’s memoirs, like others by Baghdadi Jews that have appeared in recent years, are therefore precious as the testimony of a rapidly disappearing population.

The first volume of Somekh’s memoirs was a collection of vignettes and meditations on his youth in Baghdad in the 1930s and 40s. It was an often colorful introduction to what life was like for a bookish, middle-class Jew in that city, an elegant complement to superb memoirs by similarly bookish Baghdadi Jews such as Naim Kattan’s Farewell, Babylon: Coming of Age in Jewish Baghdad and Nissim Rejwan’s The Last Jews in Baghdad: Remembering a Lost Homeland. Other recently published memoirs considerably expand the range of first-person perspectives on Jewish Baghdad. For instance, Violette Shamash’s 2008 Memories of Eden: A Journey Through Jewish Baghdad recounts her youth and young adulthood in a family so wealthy that King Faisal once considered purchasing their villa for his own residence, while Badri Fattal’s 2005 Chalomot be-Tatran (Dreams in Tatran) is a Hebrew account of his early life in the Jewish slums of that city.

Life After Baghdad, by contrast, deals with Somekh’s first impressions of Israel, his years in the Israeli Communist Party and in Arabic literary circles in Israel (the two were closely intertwined), and his career as a student and professor both in Israel and during stints abroad in places such as Oxford and Princeton. His is certainly a success story: Somekh was offered a position in the prestigiously stuffy Academy of the Hebrew Language in the 1960s and held the Halmos Chair in Arabic Literature at Tel Aviv University from the early 1980s until his retirement in 2003. Somekh gives us brief accounts of figures who influenced his life and career, such as the brilliant, blind linguist Chaim Blanc, the communist Hebrew poet Alexander Penn, and the eminent historian S. D. Goitein.

Where Life After Baghdad is more than a merely chronological continuation of the first book is in its focus on the author’s relationship with Arabic language and literature, and by extension with the Arabic world in Israel and beyond. Baghdad, Yesterday sketched the origins, in interwar Baghdad, of his lifelong love for Arabic literature. In the new book he informs us: “The primary goal of this memoir is to reconstruct the ongoing attempts I have made to hold a discussion—even a dialogue—with Arab intellectuals and writers: Egyptians, Iraqis, Palestinians, and others, in the Middle East and elsewhere.”

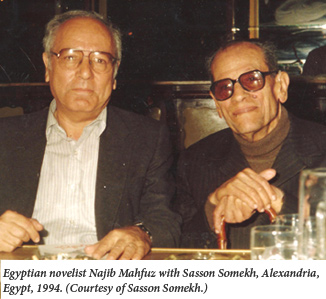

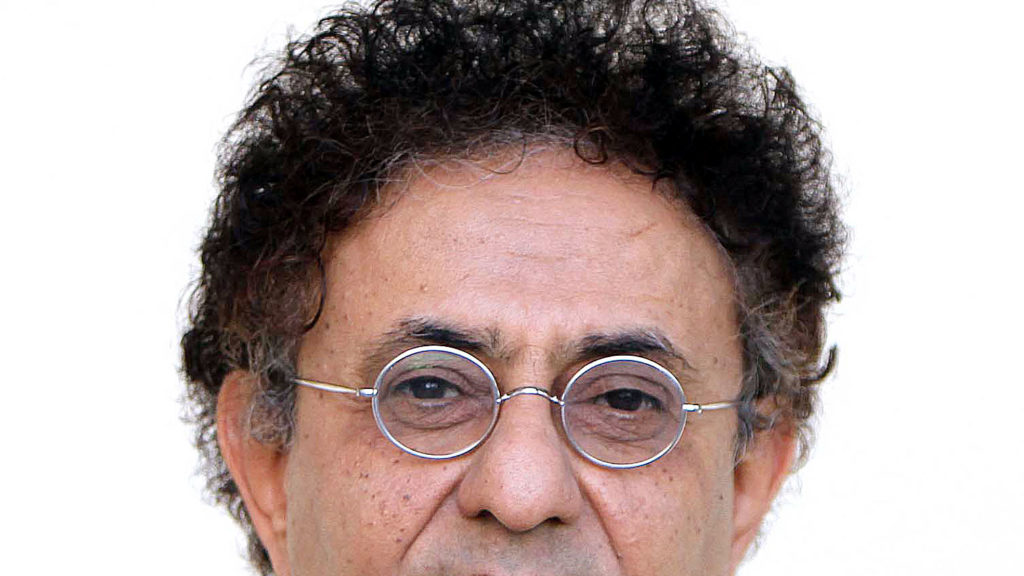

His focus in this regard is especially on Egypt—the last third of the new book could be titled “Cairo, Yesterday.” Somekh reflects on his sojourns in Egypt, including his time as director of the Israeli cultural and academic center, which was created in the 1980s and has maintained a beleaguered existence since. He devotes a significant part of his book to his encounters with Egyptian writers and intellectuals, above all the Nobel Prize-winning novelist Najib Mahfuz, who was the subject of Somekh’s doctoral dissertation and the object of his devotion as both writer and friend.

One does not end the book with a sanguine view of the prospects for a Jew who wishes to take part in the world of Arabic literature today. Somekh cannot help but note the anti-Semitism and gross anti-Israelism he encounters in Egypt, the erasure of Anwar Sadat from Egyptian history, the refusal of writers on whom Somekh has written scholarly studies to meet with him in public lest they pay the political price—or worse. (Mahfuz was nearly stabbed to death because of his willingness to consort with Israelis.)

Somekh surely knows that by framing his book in terms of his desire for an Arab-Jewish dialogue he is conjuring the famously sobering writings of a figure who was something of an inspiration to him: Gershom Scholem and his letters and essays on the German-Jewish dialogue. Scholem was not unsympathetic to the German Jews’ efforts to find a home in their country’s culture. “No one,” he wrote, “not even one who always grasped the hopelessness of this cry into the void, will belittle the latter’s passionate intensity and the tones of hope and grief that were in resonance with it.” And yet Scholem insisted that there never was any true dialogue between Jews and Germans, because the Jews were never engaged “with regard to what they had to give as Jews” but rather “what they had to give up as Jews.” Somekh’s ardent hope is that Scholem’s words will not be ultimately applicable to the Arab-Jewish dialogue he has spent a lifetime pursuing.

Somekh’s English memoirs bear different titles than their Hebrew originals, and in both cases the most significant difference is that they have, as the originals do not, subtitles: in the first case, “The Making of an Arab Jew,” and in the second case, “Memoirs of an Arab-Jew in Israel.” Not a little ink has already been spilled both in Israel and the United States over the term “Arab Jew.” In a judicious 2008 article on the subject, Princeton scholar Lital Levy observes that the Arab Jew is “a concept gaining increasing acceptance and purchase in academic discourse” and that it is deployed as part of, in Levy’s phrasing, “a political project of intervention into the normative terms of Zionist discourse.” Or, to put it more plainly, left-wing professors have found the concept of the Arab Jew useful in their critiques of Zionism, Israel, and American Middle East policy. The frequent implication of these discussions is that there was once, and ought still to be, a population of Arab Jews who were an integral and harmonious part of Arabic culture, and there might yet be if the political and mental structures of nationalism and colonialism, especially Zionism, were to be dismantled. Levy cautions, however, that the concept as used by these academics is not grounded in historical reality. “[I]n using the term ‘Arab Jew,'” she says, these academics “cannot assume the historic existence of a pristine Arab Jewish subject whose holistic identity was shattered by colonialism, Zionism, and Arab nationalism.” The focus of this project, then, is less on the historical actualities of Middle Eastern Jewish experience than on radical opposition to the institutions these academics seek to critique.

From a straightforward linguistic standpoint, it is certainly problematic to use the term “Arab Jews” to refer to the Jews of the Middle East. In Life After Baghdad, Somekh declares:

I am fundamentally opposed to the term “Arab Jew” as a general term for Middle Eastern Jewry, just as I disapprove of its use by Jews and Israelis abroad as a display of solidarity with these ethnicities despite not having the faintest knowledge of Arabic in either its contemporary or medieval form. [My translation.]

Historically speaking, the fact is that many Jewish communities in the modern Middle East did not use Arabic as their primary spoken or written language. Somekh points out that in modern Egypt, for instance, only a minority of Jews ever spoke or wrote primarily in Arabic. André Aciman, in Out of Egypt, a memoir of his childhood in 1950s Alexandria, describes his miserable failure attempting to learn Arabic as a schoolboy. “Very few of us understood a word of classical or formal spoken Arabic,” he writes of his social set. “All we knew was street Egyptian, a sort of diluted, makeshift lingua franca that Egyptians spoke with Europeans.” The languages of Aciman’s childhood were English, French, and Italian, not Arabic, except for those bits he picked up from listening to servants. The major modern Jewish writers to emerge from Egypt have tended to write in English, like Aciman, or French, like the poet Edmond Jabès.

Somekh, too, in the first volume of his memoirs, describes his upbringing in a household in which Arabic was one facet of a polyglot existence. From the last decades of the 19th century, more and more of Baghdad’s Jews were educated in the European-administered Alliance Israélite Universelle schools springing up throughout the Middle East, and their schooling focused primarily on French and, somewhat later, English. Somekh’s mother, who attended an Alliance school in Basra, never learned written Arabic. While Somekh’s father acquired some knowledge of written Arabic, he preferred to read Life magazine, and his mother was a regular reader of Ladies’ Home Journal. “In fact,” writes Somekh, “there wasn’t an Arabic book or newspaper in our house, at least not until I started to bring some books and journals home.” As Somekh notes, “a rather complicated linguistic state reigned” in his household. Describing his father, Somekh writes:

He would speak Jewish Arabic at home and move to Muslim Arabic on the street; at work, he spoke English with the bank’s British managers and various dialects of Arabic with the customers. He wrote bank records in English, and then read English and French when he came home.

Somekh’s own schooling continued this pattern. The Jewish high school he attended in Baghdad “had a strong English-language bent,” and while by the end of the 1920s the government required instruction in Arabic, “the school’s administrators and (to a greater degree) the pupils and their parents were not deeply concerned about the level of its Arabic-language studies. Their principal interest was English.” It seems, if anything, rather limiting to refer to this multilingual population as “Arab Jews.”

But what of the Arabic that, as Somekh notes, was spoken by his parents and by most Baghdadi Jews at home? Didn’t that make them, at least in a linguistic sense, “Arab Jews”? Not necessarily. What these Jews spoke was a specifically Jewish dialect of Arabic that had the effect not of signaling its speakers’ membership in a broader Arab community, but rather of marking them as audibly different: a minority population, non-Muslim and inferior. “We had only to open our mouths to reveal our identity,” writes Naim Kattan in an oft-quoted passage from his memoir describing how, during his youth in 1940s Baghdad, the Arabic language was more a source of division than of commonality. Because the various religious, ethnic, and regional groups each spoke Arabic differently, the “emblem of our origins was inscribed in our speech.” When speaking Arabic, “we were Jew, Christian, and Muslim, from Baghdad, Basra, or Mosul.” In the presence of even a single Muslim, the Muslim dialect was imposed, and deviations from it were the stuff of demeaning comedy. Somekh, too, in the introduction to the Hebrew original of the first volume of his memoirs, writes that it was a fundamental part of the identity of the Jews of Iraq that they spoke “the Jewish dialect specific to Baghdad and southern Iraq, fundamentally different from the idiom of the Muslim population of that region.” One could argue, I suppose, that the use of Judeo-Arabic makes its speakers Arab Jews in the same way that the use of Yiddish makes its speakers German Jews, though few if any Jews or Germans ever thought that.

The concept of the Arab Jew is not solely linguistic, however. It is also political, and this is what makes the term both so interesting and so contentious. Somekh does claim the term Arab Jew for himself and his generation, writing that “Iraqi Jewry (primarily that from Baghdad and Basra) is unique in that it adopted modern literary Arabic as its vernacular beginning in the first decades of the 20th century.” This may be overstating the case somewhat, as Kattan’s description of the continuing awkwardness around dialects indicates. Yet Somekh is certainly correct that his generation of young, primarily middle-class Baghdadi Jews did turn enthusiastically to modern literary Arabic, in their speech, in their literary-cultural aspirations, and—most significantly—in connection with their political hopes.

The most extensive and analytically elegant treatment of this shift is Haifa University professor Reuven Snir’s book ‘Arviyut, Yahadut, Tsiyonut: ma’avak zehuyot bi-yetsiratam shel Yehude ‘Irak (Arabness, Jewishness, Zionism: A Clash of Identities in the Literature of Iraqi Jews), which one hopes will be translated into English in its entirety one day soon. Snir describes how the generation of secular middle-class Iraqi Jews who came of age in interwar Baghdad and Basra responded powerfully to the idea of Arabism, which had been originally created to forge an Iraqi national identity for a state stitched together from various formerly Ottoman provinces. These Arab Jews helped to create a brief-lived liberal Arabist cultural vision that reflected their optimism and, later, stubborn insistence that they would be accepted as equal participants in an enlightened Iraqi polity. They walked the path from idealistic identification of Iraqi nationhood with modern liberal enlightenment to the bitter disappointment that their love for their nation and its real or imagined Arabic culture did not translate into political, social, or even cultural acceptance.

The notes of early optimism were stirringly hopeful. “The night of tragedies and calamities has reached an end,” declares a poem that was recited in a Baghdadi synagogue to celebrate Faisal’s coronation, “the heavy darkness withdraws from us. Despite differences in religion, we trust in a homeland whose law unites us.” The poet and short story writer Anwar Shaul, perhaps the central figure in the Arab cultural vision of Iraqi Jews, wrote a poem whose lines would later be quoted by Iraqi Israeli novelist Shimon Ballas. “Indeed I draw my faith from Moses,” wrote Shaul, speaking for his generation of Baghdadi Jews, “yet I live under the protection of Muhammad’s law, Islam’s tolerance is my refuge, and the artistry of the Qur’an’s speech is my source, that I am of the Mosaic religion does not mar my love for Muhammad’s nation.”

Kattan describes movingly the love and sense of ownership that he and a high school friend had for Arabic and its literature: “We never tired of discovering the rhetorical wealth of our language and we enjoyed repeating the words, rewriting the sentences of our great writers, thereby declaring our own virtuosity in handling the whole range of its unique music.”

Somekh describes his own shift in this regard. Like his parents, Somekh, too, was passionate about English, “my bridge to European culture.” And yet at some point in his teens, he became uncomfortable with what he felt was a “split personality” in which Arabic was spoken but not read, widely available but not esteemed. He began to take an interest in the Iraqi Jews who were writing Arabic literature and to try his own hand, first at short stories and soon at poetry and translation. “Here I was,” he says, “an Arab Jew in whose home and at whose school Arabic was treated with disdain.” It might be more accurate to say that Somekh desired to become an Arab Jew—an equal and active participant in the Iraqi nation and its new culture—and therefore followed the linguistic consequences. The embrace of Arabic and claiming of Arab or Arab Jewish identity by the educated, middle-class Jews of Baghdad and Basra was part of a political project. It was both a vehicle for and expression of hope for a modern Iraqi identity that could include Jews, Christians, and Muslims equally as citizens of a modern Iraqi nation.

And yet this possibility of belonging to a common nation through the Arabic language proved illusory. Kattan and his high-school friend Nessim found that no matter how brilliantly they distinguished themselves in their Arabic lessons, they would never be perceived as part of an Arab or Iraqi nation. They were Jews, and so their love for and ability in Arabic was a priori illegitimate. If they distinguished themselves in Arabic, it only made them stand out more painfully—as Jews.

We soon realized that our blind enthusiasm, our frantic love for the masters whose heirs we claimed to be, were not shared by our classmates. And it was that admirable interpreter of the millenary message of unalterable beauty, our literature teacher, who most objected to our enthusiasm. He would question the whole class about a grammatical ambiguity or a complicated figure of speech. Nessim and I were usually among the first to raise our hands, pointing out with joy that we held the key to the mystery. The teacher never called on us . . .

Once Nessim was the only volunteer in a desert of ignorance and silence. He raised his hand. The teacher, who could not push his objection to that point, gestured. In a trembling voice, Nessim gave the answer, but the teacher merely told him to sit down.

The next day we were the only ones who knew the meaning of a verse from the Qur’an. Nessim raised his hand timidly, then lowered it. He nudged me with his elbow, urging me on. The teacher stared at me, looked at my raised hand and, without faltering, concluded, “So, no one has put up his hand.”

The Syrian Arab nationalist Ali al-Tantawi observed precisely this dynamic when he taught in Baghdadi schools in the 1930s. In his memoirs he recalls how an anti-Semitic principal could not stomach the fact that the Jewish students repeatedly got the best marks in Arabic. Two weeks before an Arabic examination, the principal decided to base the grade instead on tests in Islamic religion and Qur’an. To his exasperation, the Jewish students still got the highest grades.

Indeed, one of the core elements and, in retrospect, misjudgments of this Arabic Jewish project was the notion that Arabism could be disengaged from Islam. Snir writes that the dream of these Jewish writers and intellectuals foundered on a paradox: their desire to embrace a culture while ignoring that culture’s decisive connection with a religion. Fouad Ajami, in The Foreigner’s Gift: The Americans, the Arabs, and the Iraqis in Iraq, goes even further, arguing that Iraqi Arabism was simply an ideological tool to maintain the supremacy of the ruling Sunni minority:

The idea of Arabism was thus both false and cruel . . . Indeed it was destined for greater cruelty as it was transmitted down the social and economic order to military officers and displaced peasants armed only with their resentments and their will to rule and to hoard what was there to be had of state wealth. By the time Arabism and all the ideological pretenses made their way down from the old Ottomanist class to the generation of Saddam Hussein and his lieutenants, Arab nationalism Iraqi-style had hatched a monstrous new world.

Even the liberal model of Iraqi identity that seemed to offer such promise in the 1920s was premised on defining Jews as simply another kind of Arab—not as Iraqis. It therefore made tacit and not-so-tacit demands upon Jews prior to admitting them into a national compact.

Given the tension between the Arabist cultural vision of Iraqi Jews and what would prove to be the inability of Arabic culture to allow full political and social dignity to non-Arabs and especially non-Muslims, the fascinating figure of Ahmed Soussa becomes all the more important to assess. An anti-Jewish writer and polemicist, Soussa began in the 1920s to attack Iraqi Jewish intellectuals (as well as the Jewish community as a whole) for what he charged was its divisive Jewish chauvinism, meaning in his case that even talk of “Arab Jews” or “Arab Iraqis of the Jewish faith” was a betrayal of authentic Arabic culture and Iraqi nationality both. He was outraged at the cutting-edge Arabist Jewish journal al-Misbah, edited by Anwar Shaul, for, as Soussa put it in his memoirs, “focusing its attention on the happenings and interests of a particular ethnic community,” and he warned in a 1924 letter to the editors that their publication treasonously undermined “national unity” with its “Jewish zealotry”—absurd given the ardent Iraqi patriotism and Arabist integrationism of the journal.

Soussa was, in fact, born a Jew (his original name was Nissim), and he would explain his 1936 conversion to Islam as partly the expression of his Arabism, making precisely the connection between Arabism and Islam that Arab Jewish intellectuals of the time sought to deny or downplay. To be a Jew was an accident of birth, a deformity to be corrected in a new, truly Arabic (because it was also Islamic) identity that left little room for any other allegiance. As he wrote in a 1930 broadside against Jewish particularism:

You Jews of the Arab east: the Arab states have given you great wealth and happy lives. Therefore you are obligated to cry out as one: we were born Jews but we are Arabs before everything else.

He would go on to write several books purporting to show how Jews had falsified history in order to make it appear that they were indigenous to the Middle East, when it was of course the Arabs who were the original Semites. He dedicated one of them, Arabs and Jews in History, to Saddam Hussein.

How poisoned the relationship between Jews and Arabic in Iraq could be is also memorably portrayed in Mona Yahia’s autobiographical novel When the Grey Beetles Took Over Baghdad, which draws on her childhood and youth in 1950s and 1960s Baghdad in one of the few hundred or so Jewish families left in the country after the mass exodus of the early 1950s. (Yahia escaped the country in 1970 and moved to Israel and then Germany.) In the final chapters of the novel, the Ba’ath party has taken over. Jews are rounded up as Zionist spies and hung in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square to the delight of enormous crowds.

As state-sponsored anti-Semitism and anti-Israelism dominates Iraqi life, the protagonist, a high school student, finds herself declaring war on her own language because it seems to have declared war on her. She thumbs listlessly through the jingoistic readings in her state-mandated school textbook on contemporary Arabic literature, acutely aware that she is not considered to be part of the nation lauded in such readings as “The Call of the Soil,” “Salute to the Iraqi Republic,” and “Valley of Blood.”

She decides to erase the word watan, Arabic for “homeland,” wherever she finds it in the book, “eliminating one watan after the other, delicately, like a soldier dismantling bombs in a minefield.” In contrast to Kattan and the other young Jews of the interwar period who reveled in their command of literary Arabic, yet in tacit sympathy with their similar experience of being silenced by the state’s definition of the Arab nation, Yahia’s protagonist goes on to “remove each word that evokes homeland or associates it with heroism, chivalry, nobility, honour, faith, virtue, martyrdom, motherhood, manhood, brotherhood, life, freedom, blood, beauty, loyalty, soul, and glory.” Her achievement, she realizes, as she sees how the readings have been reduced to incoherent jumbles, is that: “I have at last forced Arabic to stutter.”

She goes further, devising a plan that will enable her to forget the Arabic language entirely:

The dictionary at my side, I conceive a systematic programme of unlearning Arabic. It consists of twenty-eight stages which correspond to the twenty-eight letters of our alphabet. At each stage I will omit from my speech and writing all the words beginning with a particular letter.

When she confides to her best friend her intention to unlearn Arabic, her friend is shocked: “But Arabic’s your mother tongue!” She responds:

With such a mother, we can envy the orphans! How are we to live with the abuse they pour on us: bloodsucker, vulture, poisonous snake, cancerous growth, child of a whore, agent of the devil, error of humanity—just take your pick, you’ll end up hating yourself anyway.

She has made her decision: “Arabic has been silencing us for the last fifteen years! It’s my turn to silence it. I’m disowning it, it’s as simple as that.”

Her friend tells her that this is impossible. English and French will always “remain your second languages,” she warns, “second best, like crutches. You know what that means? Your memories will be scattered, full of gaps. Your heart will be divided . . . your feelings confused.” And, indeed, Yahia’s autobiographical novel, her first and—to date—only book, did not appear until more than a quarter century after her harrowing escape from Iraq. Nevertheless, the book, written in engaging English prose, is itself a kind of rebuttal to her friend’s linguistic pessimism.

The emergence of the Arab Jew in 20th-century Iraq was therefore a largely unrequited love for an Arabic culture that Jews dreamed could be cosmopolitan and non-confessional, and for a liberal national identity that never quite came into full existence. What strikes one most about the Iraqi Jewish experience, therefore, is not its difference from modern Jewish experience in Europe, but its decided familiarity.

Other young generations of Jews in other parts of the world have found enthusiasm for a new national language as an expression of their cultural and their hoped-for political integration into a modernizing nation. Whether we speak of young Russified Jews in turn-of-the-century St. Petersburg, or the Jews embracing Polish in interwar Warsaw, or, say, the Moravian and Bohemian Jews who opted for Czech instead of German, these linguistic decisions, cultural possibilities, and political contradictions are not an exclusively Middle Eastern or Iraqi Jewish phenomenon but rather a familiar part of the modern Jewish experience.

The Iraqi Jews of Somekh’s generation sought to celebrate their Iraqiness and their Arabness by defining Iraqi nationalism as a kind of liberalism, glossing over the connection between Arabic culture and Islam. The pattern is familiar from much of European Jewish experience in modernity, in which Jewish communities in Germany, for instance, fell in love with the idealized Enlightenment Germany of Schiller and Goethe, yet found all too often that their prowess in and love for the language was not taken as a sign of their belonging but of what the majority culture resented as a de facto contradiction. The basic dilemma was posed by Moritz Goldstein in his famous essay “The German-Jewish Parnassus.” The desire of Kattan’s generation was, in Goldstein’s words, “to administer the spiritual possessions of a people that denies us the capability of doing so.” In Isaac Babel’s “The Story of My Dovecote,” to take another example, a Jewish student tries to win a spot in Odessa’s best gymnasium by spouting perfect geysers of Pushkin’s verse, to which the Russian examiners respond “What a devil is in these yids.” In Iraq, as in much of Europe, the passion of Jews for a national culture and language was taken too often not as evidence of their belonging, but of their alienness.

As it happens, Franz Rosenzweig, describing his vision of German Jewry as a culture to be nourished by twin sources—the enlightenment universalism of Germany and the traditions of Judaism—characterized this vision as a “Zweistromland“—a land of two rivers, i.e., Iraq. It is not that the Iraqi Jewish experience is identical to the German or Russian or any other European Jewish experience, but that it seems to have been informed by the same set of political and cultural tensions that have shaped Jewish history in the modern period. The Iraqi Jews of Somekh’s generation and milieu believed that they could help foster and participate in an Iraqi national identity that would be nurtured by Arabic culture, while defining this Arabic culture in universal terms that were divorced from its historical, religious, and political realities.

And so they encountered the same problems and opportunities as other modern Jews have experienced in other national contexts. Arab identity was claimed by Iraqi Jews in part because it was not secure. It was contested, challenged, debated, denied. It was something in the making, and therefore welcomed makers. But when Jews claimed Arabness they only made themselves more conspicuous as Jews. And the Jewish component of their identity was itself always either an insurmountable problem or on the verge of being erased, or both. And then the whole cosmopolitan project collapsed.

The experience of Jews in modern Iraq does not present us with an escape from the conundrums of Jewish history. Yet it is no less fascinating for that, and no less deserving of accurate remembrance.

Suggested Reading

Workday Jews

In their respective books, Chad Alan Goldberg and Eliyahu Stern address the question of whether the Jews are the quintessentially modern people or a people who came to modernity late and with a sudden shock. They reach very different conclusions.

Manufacturing Falsehoods

An immense echo-chamber has been built, and the line is always the same: Israel is not allowed to be a country like any other.

A Murder in Queens

The murder conviction of Marina Borukhova in 2008 shocked the Bukharan Jewish community of Forest Hills. But many questions remain unanswered.

Fanny and Hilde

If Court Jews provided economic services, the salon women provided cultural ones that were rarely available to rulers and other nobles in the stuffy environs of aristocratic society.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In