Homer of Lod: The Indispensability of Erez Bitton

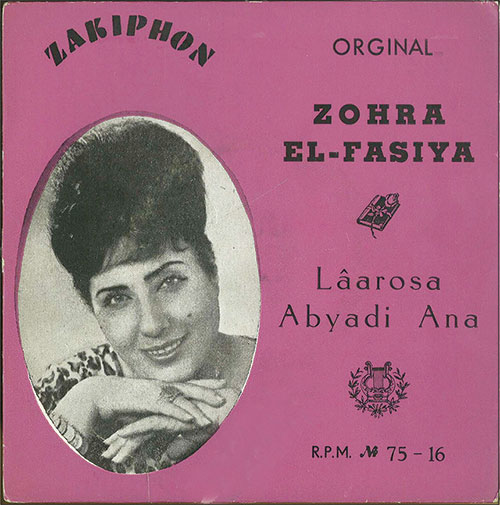

It is said that when she sang

Soldiers fought with knives

To push through the crowds

To reach the hem of her dress

To kiss her fingertips

To thank her with a rial coin

Zohra el-Fassiya

From “The Song of Zohra el-Fassiya,” 1976

One day in the late 1960s a young social worker and his secretary appeared at an apartment in the tenements of Ashkelon. The old woman who lived there had asked for help from the local welfare office, so the pair of officials walked over to pay a house call and vet her claim. The woman wore a housecoat and heavy makeup. She had carpets stacked on a cot of the kind the Jewish Agency used to issue to immigrants—she said her carpets were too expensive for the floor of such a poor apartment. She knew no Hebrew and spoke her native Moroccan Arabic.

The neighborhood was one of the many blighted areas in Israel home to hundreds of thousands of immigrants from the Islamic world, living on the physical and mental periphery of a young state founded by and largely for Jews from Europe. The general name for these people is Mizrahim, “easterners.” Israel’s leaders were not sure what to make of them—Jews with scant interest in socialism and no ties to the Ashkenazi heartland, people unwilling to abandon their deep religious attachments who came with the language, songs, and mannerisms of the Arab enemy.

The social worker, Erez Bitton, had come from Algeria as a child. He was struck by the woman’s dignity despite her reduced circumstances and also by her love of Israel. She would not speak ill of the country. “She had these carpets on a bed,” he remembered years later, “as if she was still traveling and hadn’t unpacked, as if she hadn’t yet reached the Land of Israel.” But she had hung portraits of Ben-Gurion and Weizmann on the wall.

When Bitton arrived back at the welfare office, his colleagues asked if he knew who the woman was. He didn’t. That was Zohra el-Fassiya, they told him—the court singer of Mohammed V, king of Morocco.

Today you can find her in Ashkelon near the welfare office

The smell of leftover sardine tins on a wobbly three-legged table

Kingly rugs stacked on a Jewish Agency bed

And she, in a fading housecoat

Lingers for hours at the mirror

Wearing cheap makeup

And when she says, “Mohammed the Fifth, apple of our eye”

You don’t understand at first.

Zohra el-Fassiya has a hoarse voice,

A clear heart, and eyes sated with love. .

A few years after Bitton met Zohra el-Fassiya, on October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria attacked Israel on Yom Kippur and all of Bitton’s friends disappeared into the army. He was left alone. The war was the country’s greatest shock in the 25 years of its existence. It killed more than 2,500 soldiers and discredited the Labor Zionist heroes of independence, who suddenly looked like fools or worse. The confidence of the old establishment cracked, and, within a few years, their opponents would win an election for the first time. Voices that had been faint began to speak louder: a movement of settlers who believed they could bring the Messiah by building houses; militant Mizrahim inspired by a group that called itself the Black Panthers, after the American revolutionaries; people demanding “peace now.”

Bitton had written some poetry before. It was mostly about love and loneliness, he told me recently, “like any young person.” He tried to write like Bialik, the father of modern Hebrew poetry, but it wasn’t really working.

Around this time Bitton tried something else: poems about people like him and his parents, the poor of North Africa and the Middle East, Jews torn from their old homelands and lost in their new one. Until then, Hebrew poems and songs were about the inner lives of the new Israelis who were part of the civilization of the West, or about the beauty of Israel’s hills and valleys. They weren’t about the tenements of Ashkelon, or about where the people in those tenements had lived before. Bitton still isn’t exactly sure what the 1973 war had to do with the change in his writing, but he started mixing Arabic with his Hebrew. He used the names for the spices of his childhood home in Oran, Algeria, like lebzar, and the names of musical instruments, like the drums called tamtam and the stringed rababa.

He remembered the faded beauty of the woman in the apartment and wrote a poem about her. “The Song of Zohra el-Fassiya” appeared in his first collection, A Moroccan Offering, in 1976. “There was a feeling,” two admirers wrote in a collection of essays about him published in 2014, “that this was the moment of the birth of Mizrahi poetry.” If there was a poem of Bitton’s that announced the birth, it was “Summary of a Conversation”:

What does it mean to be authentic?

To run down Dizengoff St. shouting in Jewish Moroccan,

Ana min el-maghreb, ana min el-maghreb

In Israel of the 1970s everyone was supposed to speak Hebrew and forget the past. There would be no Yiddish, there would certainly be no Arabic, and being from the Maghreb—a fluid Arabic term encompassing Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia—was nothing to be proud of. Shouting “I’m from the Maghreb” in the confident heart of the new Israel—and in Arabic—in those days was daring. The same poem goes on to imagine the poet sitting among Ashkenazi intellectuals at the nearby Café Roval wearing a colorful Moroccan robe.

All of this might seem innocuous now. But Bitton’s poems had an electrifying effect on many readers—particularly young Mizrahim who had been given the impression in school, as one put it, that their parents arrived “from a smooth and empty place, like the surface of the moon.” That writer, Sami Shalom Chetrit, remembered a school classroom of “forty Mizrahim and one good-hearted Ashkenazi teacher” where he received no inkling of the cultural riches of his Moroccan family, or of any of the Jews who poured into Israel from the Islamic world after 1948. (Today roughly half of Israel’s Jewish population has roots in Islamic countries.)

Few of the stories the new state told about itself—“from annihilation to rebirth,” the kibbutz, Herzl—had much to do with people from Casablanca or Tehran. Their culture wasn’t welcome in public, beyond fragments quarantined as folklore. Some of the greatest Iraqi musicians had been Jews, like the famous brothers el-Kuwaiti, and there was Zohra el-Fassiya, of course, and many others—but the music wasn’t on the radio, kept alive only in living rooms, at private parties, and in small clubs in the area of south Tel Aviv known as the Yemenite Vineyard. This culture wasn’t “Israeli.” It was primitive, and its proximity to the culture of the enemy made it a bit dangerous. Yitzhak Gormezano Goren, an Israeli writer born just down the coast in Alexandria, Egypt, wrote in his 1978 novel Alexandrian Summer (released in English in 2015) that Israel of those days felt like Eastern Europe: “I might as well be sitting on the shore of the Baltic Sea, for all the distance I feel from the Mediterranean, which can be seen from my window in Tel Aviv.”

Even among Jews from Islamic counties, the North Africans were considered to be the poorest and least civilized. Bitton had once been ashamed of his own mother, whom he described to me as “the kind of mother with a kerchief on her head, a Jewish woman who looked like an Arab.” Now he wanted everyone to know her, and his father, who “sanctified the Sabbath with clean arak,” the anise liquor of the Mediterranean. He introduced his readers to Efraim Manofla, a music teacher reduced to playing his broken mandolin at the Tel Aviv bus station, and Aysha, daughter of Mas’ouda, “about whom it was said that a child died in her womb, and the women would spit when she passed and say, ‘Allah guard us.’”

Mizrahi characters with strange accents and behavior had become staple figures of fun in the brash popular culture of the young state, showing up regularly in comedy films. “Frecha,” a common name for Moroccan girls, was turned into an epithet for a woman of Middle Eastern background, somewhere between “ditz” and “slut.” Bitton put these names in his poems and chanted them as if they were blessings.

On YouTube, you can hear him reciting “The Song of Zohra el-Fassiya,” and the name of the singer becomes a kind of song in itself: Zohra el-

Faseeeeya. In one poem Bitton took the name “Frecha” and gave it to a grandmother at a beautiful Moroccan wedding with Marrakech wine and Atlas cushions, singing an Arabic melody to the bride and groom. Who else was coming to this wedding?

From one end of the village to the other

Arabs and Jews we will come

Did he mean that the guests included Arabs and Jews? Or that these people were simultaneously Arabs and Jews? You weren’t sure, but you definitely wanted to be there. Bitton wasn’t haranguing you or asking for pity for himself or his subjects. He was simply describing his world with enough power to convince you that you’d been missing out on something great. He was suggesting an Israeli identity that included God, the gutter, sex, rabbis, Hebrew, Arabic, the Atlas Mountains, and Dizengoff Street. If that sounds familiar, then you’ve spent time in Israel over the last few years: a country of medieval Sephardic liturgy on Top 40 radio, celebrity selfies at the graves of holy rabbis, the Andalusian Orchestra, and Umm Kulthum tattoos.

In the common narrative about this country, Mizrahim joined the story of the European Jews who established the state, and they remain on the margins of that story. But if you think of “Mizrahim” as the Jews living inside the world of Islam, then this description now applies to all of the Jews in Israel. So another way to see things is that the founding of Israel meant the Jews of Europe became part of the Mizrahi story.

There’s a way of being Jewish in the Middle East. It isn’t the transformative socialist experiment pictured by Israel’s founders or the listless post-everythingism of modern Europe and North America. It involves an affinity for tradition, community, and family, combined with a love of life and the beach; a tribal suspicion of the neighboring tribes; Arabic words, Middle Eastern food, and Middle Eastern music. That’s the version of the country coming together now. It’s one that makes sense if you’re here, but which is becoming harder for people from the West to access or understand. It’s recognizably Erez Bitton’s country. That makes him an essential voice for anyone trying to figure this place out.

“What does it mean to be authentic?” asked a younger Israeli poet of Iraqi heritage, Almog Behar:

To write poems about Erez Bitton

And hope that one day I’ll run down Dizengoff shouting:

Ana min Baghdad, ana min Baghdad

In one of his recent poems Bitton returned to the pivotal moment of his early life:

On that wounded night

My father made a feast for the neighbors with wine and delicacies

While my mother unraveled her two eyes to the crows.

And the neighbor women on tiptoes

Going out and coming in to light candles

In honor of Rabbi Meir the Miracle Worker and Rabbi Shimon Bar-Yochai.

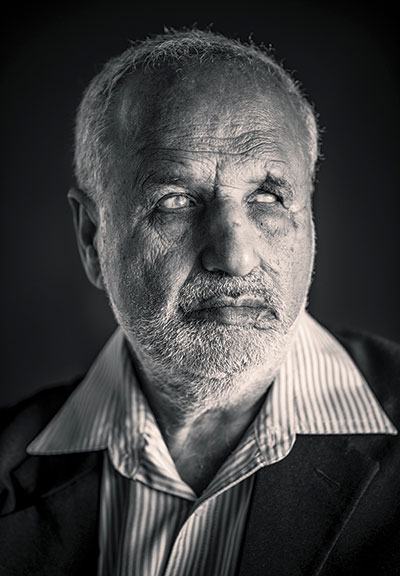

In the fall of 1951 Bitton was 10 and was still named Ya’ish. He was playing with a friend in the orchards of Lod, the hardscrabble city where his family lived alongside other immigrants in the homes left behind by Arabs in the war three years before. The two boys found something interesting and were playing with it. It was a grenade left behind by the army, or maybe a bomb left by Palestinian fedayeen—he doesn’t know. When it exploded he lost his left hand and the sight in both eyes.

After that he went to the Jewish Institute for the Blind in Jerusalem, where a kind counselor gave him new clothes and, just as casually, a new Hebrew name to replace his Arabic one. He learned Braille and Bialik, and went to university. He married an architect, Rachel, who became his literary partner and champion. He went on to publish five poetry collections in Hebrew. He has won nearly every literary honor the country can bestow, including the Israel Prize. Last year, the translator Tsipi Keller brought him to an international audience with a first English collection, You Who Cross My Path.

Bitton never saw Zohra el-Fassiya, her makeup, or the portraits of Ben-Gurion and Weizmann on her wall. These things were described to him by his secretary, who also held his hand as they crossed the street. He has never seen his wife, although he knows she’s beautiful. He once wrote that he “lives beside her beauty like a rumor.” He has never seen their two children. He hasn’t seen anything since he was 10.

The novelist Yitzhak Gormezano Goren attended a meeting of Mizrahi activists in 1980. “Among them stood out a man who was sitting straight in his chair without moving, his hands on his knees, his scarred face looking up,” Goren remembered. “When he spoke his body didn’t move, and the words came out of his mouth with a kind of fluency that was almost without pauses, words that seemed carved in stone.” Goren, who was also a stage director, found himself mentally giving out roles for each participant to play in the resurgence of Mizrahi awareness. Bitton, he decided, would be the prophet.

Bitton’s poetry is not overtly political, but he has always been political himself. In the early 1970s, when the Israeli Black Panthers came out of one of the Jerusalem slums and were marching against the condescension and neglect of the Ashkenazi ruling class, he identified with them. He remembered hearing on the radio that Sa’adia Marciano, one of the Panthers, was lying in the middle of Zion Square in Jerusalem blocking traffic—he hadn’t heard of anything like it before. It had real power.

In 2015 the education minister Naftali Bennett invited Bitton to lead a team of experts putting together a government report on Mizrahi content in schools. The Bitton report caused a furor when it was published last year, having concluded that Israeli students were learning nearly nothing about the cultural heritage of half of Israel’s Jewish citizens. “It would not be going too far to say,” the poet wrote in the report, “that we were shocked by the absence of attention paid to Mizrahi Jewish identity in the formal and informal systems of education.”

The 350-page document included detailed recommendations. Among those picked up in the press was the idea that if students visited death camps in Poland they might also visit Morocco and that teachers should familiarize students with North African folk traditions such as venerating the graves of saints. Bitton was quoted in a newspaper interview saying that Mizrahim were still “in the ghetto.”

The report woke up an odd and malicious creature in Israel’s basement which Israelis call the “ethnic demon.” This demon comes out a few times a year to provoke a shallow and unbearable shouting match over the place of Mizrahim in Israeli society. The trigger is either something angry coming from the Mizrahi side or something condescending from the Ashkenazi side. Two years ago, for example, it was a public speech by an Ashkenazi artist who mocked “amulet kissers.” Sometimes the trigger seems trivial, like a debate about whether Mizrahi pop music is any good and whether you’re racist if you think it isn’t. Sometimes it’s much less trivial, like the question of whether Yemeni babies were kidnapped by Ashkenazi nurses in the early years of the state. When you hear people from Morocco talking about being sprayed with DDT in the immigration camps of the 1950s and people from Poland retorting that Treblinka was worse, you know the argument has reached the bottom. It goes away for a few months and then comes back. It’s a feature of life in the country, like heat waves.

After Bitton published his report last June, the “ethnic demon” paid a visit to Gidi Orsher, the veteran film critic for Army Radio. He wrote a Facebook post addressed to all of the “Kahlilis and Zubeidas”—that is, Mizrahim with funny last names, unlike Orsher, which is not funny. Orsher suggested that if they were so enamored of superstition they should visit the graves of saints instead of doctors. “Next time you curl up in a sealed room because missiles are falling on your head, ignore Iron Dome and recite psalms,” he wrote. You could almost hear him congratulating himself for that point, which just nailed it, and then he hit “post” and was widely excoriated and suspended from his job. Anyone in Israel who hadn’t heard of Erez Bitton before the ensuing uproar had certainly heard of him by the end of it.

One of the report’s controversial curriculum suggestions was to include work by the most talked-about Mizrahi poets of the moment, a loose group of Bitton’s heirs flying under the name Ars Poetica. (The group would be worthwhile for that trilingual pun alone: the phrase meaning “a treatise on the art of poetry” in Latin includes the word ars, which in Hebrew—borrowed from Arabic—is a derogatory term for a man of Middle Eastern descent. The closest English equivalent is probably “greaser.”)

The first Ars Poetica poem I read was “Medinat Ashkenaz” (The State of Ashkenaz) by Roy Hasan. In the poem, Hasan adopts Bitton’s tactic of reciting Arabic words—but here the poet isn’t reverential but sarcastic, mocking stereotypical associations linked to Moroccans, like mufleta, a kind of fried pastry, and hafla, an Oriental party:

In the state of Ashkenaz I’m mufleta

I’m hafla

I’m respect

I’m lazy

I’m everything that wasn’t here once upon a time

When everything was white

In the lines that got him into the most trouble, as intended, Hasan tells us what he thinks about the revered (Ashkenazi) writers of the Israeli canon:

I didn’t mourn Kaniuk

And I burned the books of Nathan Zach

And I won’t celebrate your independence

Until a state is founded for me

Rather than trying to be good enough to warrant a seat at the Israeli table, like Bitton, the idea here is to tell the people at the table to go to hell and take their table. It’s not subtle, and it’s an approach the older poet wouldn’t dream of in his own work. But when I asked Bitton about Ars Poetica he said their poems struck him as “real.”

Camus described Oran, one of the main cities of French Algeria, as a place with a “cruel glitter,” whose streets were “doomed to dust, pebbles, and heat.” That’s where Bitton was born. He lived there until leaving for Israel with his family when he was six. In a poem dedicated to the Algerian poet Rabah Belamri, Bitton writes:

We both came from mothers wrapped in cloth

Like pigeons about to take wing

And lift away from the hard lands

Over there, in the Algeria of wars

He remembers going with his father to the Great Synagogue of Oran, which today is a mosque. He remembers walking with his friend Marcel to the Mediterranean shore in bright sunlight and seeing the ropes of ships tied to the docks. He described this to me when we spoke in Tel Aviv not long ago. The sea—the same one—was visible out the window of the hotel lobby where we met. The beach pulsated and rippled with thousands of bodies in the heat, the life of the city squeezed into the two hundred yards between the last buildings and the waterline.

As a young man Bitton was looking for a way to connect his old home in North Africa to his new one in Israel. He realized that the link was the Mediterranean, and in the early 1980s he began writing about his desire for an Israel that could see itself as a Mediterranean society.

Bitton and his wife Rachel, whose parents came from Greece, founded an organization they called the International Mediterranean Center, and he was invited regularly to speak in places like Spain and France. In the 1990s, the years of the peace process, he established fragile links with Muslim writers in North Africa. Most of those connections ended when the peace talks did. In recent years, as Europeans have turned against Israel in earnest, Bitton’s invitations to speak at conferences about the Mediterranean vision have dried up. If he were an Israeli who hated Israel he would be invited more, he told me, but he isn’t.

Meanwhile, Mediterranean people from Syria are fleeing slaughter to Mediterranean beaches in Greece, and a Mediterranean guy from Tunisia recently ploughed his truck into hundreds of other Mediterranean people in the Mediterranean city of Nice, killing 86 of them. The Mediterranean idea is a bit shaky at the moment, like all ideas. Things have become so bad that Bitton, who has always kept current events out of his poetry, recently wrote the draft of a poem about Bashar al-Assad, to whom he feels connected because the Syrian dictator is an eye doctor. He can’t understand how someone trained to heal eyes could order the blinding of people.

Bitton’s eyes are milky white. He doesn’t cover them with glasses. There is no mistaking his disability. But when we spoke, his responses to his surroundings and to me were so acute, and his descriptions of things so sharp, that I kept forgetting I was speaking to someone who hasn’t seen for 65 years.

As he has aged, Bitton has written more about blindness. Much of his most recent book of poetry, Blindfolded Landscapes, is about seeing and not seeing. My favorite part of the book might be an editor’s footnote that appears under one of the poems. It recounts a ride he once took with the famous poet Yehuda Amichai. The two were on their way through the desert, returning from a reading in a Negev town. Bitton asked the other poet to describe the wilderness out the window:

Amichai held Erez’s hand, and for a few minutes he said nothing.

Erez said, “Now I understand.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

We Do Not Agree on Herzl and We Still Need Hertzberg

While I would like to leave this issue behind us, I have to add one more thing.

Operation Hebrew Camp

No American Jewish camp nowadays can equal the ebullient Zionism or fidelity to Hebrew that propelled Arzt and Co. into the sky.

A Neoplatonic Affair

As the tapestry of Hillel Halkin's first novel unfurls, we see how perfectly each part fits into the larger pattern.

Lost Music

Jeffrey M. Green, Aharon Appelfeld’s translator for more than 30 years, remembers the beloved Israeli novelist.

rforstot

I have greatly enjoyed Matti Friedman's books, and now this interesting article. I hadn't heard of Erez Bitton, but as an Ashkenazi I hope to learn more. I also didn't know that Frecha was a Moroccan girls' name. Wasn't that a song by Ofra Haza also?