The Rock from Which They Were Cleft

Over the last two decades more than a million people from the former Soviet Union have immigrated to Israel through the Law of Return, which grants citizenship to anyone (and their spouse) with at least one Jewish grandparent. This has facilitated the immigration of hundreds of thousands of people who are not recognized as Jews by Jewish law (halakha). Although these newcomers and their children now identify with the Jewish people and live as Jews within the Jewish state, Israeli law—which defers to the rabbinic courts in these matters—does not allow them to marry full-fledged Jews in state-sanctioned weddings, nor are they permitted burial in a Jewish cemetery.

Many of these Israeli citizens would like to convert to Judaism. However, the High Rabbinical Court of Israel has held that would-be converts not only have to affirm an obligation to observe every single commandment in the Torah, but that their conversions can be retroactively annulled if they subsequently fail to do so, thus placing the Jewish status of thousands who have already been converted under a cloud of halakhic doubt, not to speak of personal anxiety.

In an interview last spring, High Rabbinical Court Judge Rabbi Avraham Sherman questioned the validity of “all modern-era conversions in Israel and in the world since the start of the Jewish Enlightenment period” and affirmed that Israeli converts must “undergo examination by an authorized rabbinic court before they can enter the community of Jewish people. They are not Jews for certain.” The requirement that all converts accept the commandments is, along with circumcision and ritual immersion in a mikvah, central to the halakhic definition of conversion. Nevertheless, the position that once such a conversion has taken place they are still “not Jews for certain” is surely an innovation. In fact, as rabbi and Member of Knesset (MK) Haim Amsalem has argued, there is great latitude within the tradition regarding how the requirement that the convert accept the commandments has been applied.

Last year, Amsalem published two massive and erudite volumes on conversion, Zera Yisrael (Seed of Israel) and Mekor Yisrael (Source of Israel). These books are sefarim (traditional rabbinic texts) in the best sense of that genre. The former work contains Amsalem’s halakhic discussion of a host of conversion-related matters, while Mekor Yisrael is an invaluable anthology that reproduces (in full) the halakhic writings and responsa of the more than 120 rabbinic authorities upon whom Amsalem drew in writing Zera Yisrael.

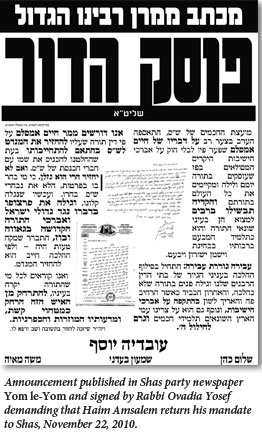

What makes Rabbi Amsalem’s position on these matters so important is his prominence on the Israeli political scene. He is the 52-year-old Algerian-born Shas party politician who has in the past couple of years outraged other ultra-Orthodox Jews, including the spiritual head of the party he represents, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, with his heterodox views. He has, for instance, denounced the “shameful” state-subsidized studies of young adult Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) men who remain in yeshiva despite having little talent for Torah study. And he has characterized Rabbi Sherman’s position as halakhic grandstanding “at the expense of thousands of converts from the seed of Israel, whom he offends, particularly IDF soldiers who give their lives, even for him.” For such heresies, Amsalem has been subjected to a torrent of abuse from the Haredi world. He was repudiated by Rabbi Yosef and expelled from the Shas party in November 2010, but, as we shall see, he has by no means left the public stage.

As Amsalem emphasizes, the Russian immigrants with whom he is most concerned speak Hebrew and lead lives that are indistinguishable from secular, or even moderately traditional, Israeli Jews. What worries him is that marriages between these immigrants and those who are indisputably Jewish “multiply daily.” He fears that this sociological fact will soon produce a distinction between what it is to be an Israeli and what it is to be a Jew within the State of Israel, forcing a potentially catastrophic split between the categories of nationality and religion in the country.

Focused as he is on an Israeli problem, Rabbi Amsalem confines his analysis and proposals of Zera Yisrael to the Israeli situation. He does not consider them to be applicable to the diaspora, nor to persons born of two Gentile parents anywhere, but only to Israelis born of non-Jewish mothers and Jewish fathers, whom he applauds for choosing to shape and share the destiny of the Jewish people. Describing them as zera yisrael (seed of Israel), he argues that their act of aliyah (immigration to Israel) bespeaks their desire to “return to the rock from which they were cleft.” Consequently, he argues that Jewish law holds that it is “fitting to love them and bring them near” when they come to convert, and this attitude “obligates us to be as lenient as possible within the parameters of Jewish law” in admitting them into the Jewish people. Moreover, he convincingly demonstrates that retroactive annulment is virtually unprecedented in the history of halakha.

Rabbi Amsalem believes that the present situation constitutes a halakhic “state of emergency.” At such moments, many earlier authorities have relied upon Maimonides in applying more lenient legal standards de jure that might otherwise only be applied de facto. Amsalem cites the ruling of famed proto-Religious Zionist Rabbi Zevi Hirsch Kalischer who, in 1864, labeled children born of Jewish fathers and non-Jewish mothers as zera kodesh (holy seed) who should be converted to Judaism at the directive of the father. He also cites a responsum from the 16th-century sage Rabbi David ben Zimri, known as the Radbaz. In dealing with the descendants of anusim, or Marranos, who had been forcibly converted to Christianity but secretly retained an attachment to Judaism, the Radbaz ruled that full “acceptance of the commandments” was not required.

Zera Yisrael also addresses the problems that arise when a conversion is sought “for the sake of marriage.” While Jewish law seemingly forbids such conversions for an ulterior motive (see Shulchan Arukh, Yoreh Deah 268:12), Amsalem points out that a number of rabbis have permitted conversion in such cases. Those who do so rely in part upon the talmudic story told of R. Hiyya who allowed the conversion of a beautiful courtesan who admitted that she was converting to marry one of his students. As do others, Rabbi Amsalem couples this story from tractate Menachot with the tale in Berakhot 31a about Hillel permitting a man to convert though he had come with the outrageous (and impossible) motive of becoming the High Priest. The Tosafot (medieval commentators on the Talmud) explain that both R. Hiyya and Hillel were able to overlook such non-spiritual motivations because they recognized that the converts in question would ultimately come to embrace Judaism wholeheartedly and selflessly. Consequently, a legal principle, “All depends upon the judgment of the rabbinic court,” emerged that grants a rabbinic court broad discretion in matters of conversion, and Amsalem shows that this principle has been widely invoked by rabbinic authorities throughout history in cases of conversion.

Amsalem addresses the question of whether Jewish law can possibly rest content with a “partial acceptance” of the commandments on the part of the would-be convert. In a remarkable paragraph, he states that the requirement of “acceptance of the commandments” is actually “not a part of the conversion process in the same way that circumcision and immersion are.” Rather, each rabbinic court convened for purposes of conversion must consider what the circumstances are that motivate each would-be proselyte to convert to Judaism. While there is surely no obligation on the part of the rabbinic court to perform a conversion in every instance, the case of Hillel cited above as well as decisions rendered by many rabbis, including 19th-century authorities Rabbi Eliyahu Guttmacher of Hungary and Rabbi David Zevi Hoffmann of Berlin, show that great rabbis have allowed conversions when they believed them to be in the best interests of the Jewish people even in instances where they knew that such converts were unlikely to become fully observant.

On this view, such a convert must certainly affirm the oneness and unity of God as well as reject idolatry and his former religion. Furthermore, in accord with the classic talmudic discussion of conversion in tractate Yevamot 47a-b, the convert must receive instruction in “some of the minor and some of the major commandments,” but he or she need not understand that this entails a commitment to observe all the commandments, nor is the convert obligated to make an explicit declaration to that effect during the conversion process. Amsalem does say that if it is understood that the aspiring proselyte has a principled intent not to observe the commandments at all, then he should not be converted. Nevertheless, even here he notes that if such a conversion is performed, then it is de facto valid and cannot be annulled. Here, along with the Shulchan Arukh, he relies upon Maimonides:

A convert whose motives were not investigated or was not informed about the commandments and their punishments, but was circumcised and immersed in the presence of three laymen, is a convert. Even if it becomes known that he became a convert for some ulterior motive, he has exited from the Gentile group once he was circumcised and immersed. However, he should be regarded with skepticism until his righteousness becomes apparent. Even if he returns to worshiping idols, he is an apostate Israelite, whose betrothal is valid. (Laws of Forbidden Intercourse 13:17)

Although it seems clear that Maimonides is categorically rejecting both the absolute necessity of accepting all of the commandments and the possibility of retroactive annulment, Rabbi Sherman and his rabbinic allies manage to read this passage as vindicating their position.

Rabbi Amsalem concludes that “in our time there are important and weighty reasons” for performing conversions for Israeli citizens who are the descendants of Jewish fathers alone—the unity of the entire Jewish nation depends upon the performance of such conversions. “Therefore, rabbinic courts are now obligated to accept these converts even when we know that they will not fulfill all of the commandments.” This will facilitate the entry of Russian immigrants and their children into the Jewish people “under the wings of the Divine Presence.” The courts, meanwhile, should “hope that the light that is in Torah will shine upon them” and ultimately bring these Jews to a full observance of the commandments.

As is the custom with works of traditional rabbinic scholarship, Zera Yisrael is prefaced by a large number of haskamot (approbations) testifying to Rabbi Amsalem’s piety and erudition. These letters come from some of the most prominent rabbis in Israel, including his teacher Rabbi Meir Mazuz, Rabbi Shear Yashuv Cohen, Rabbi Dov Lior, Rabbi Nachum Rabinovitch, and Rabbi Yaakov Ariel, among many others. Zera Yisrael and Mekor Yisrael are serious works of breathtaking and well-researched scholarship that all scholars of rabbinic literature will want to consult. And while Rabbi Amsalem is very careful in his works to circumscribe the application of his research and rulings to converts born of a Jewish father and non-Jewish mother who live in Israel, the force and substance of his arguments and scholarship extend far beyond these limits, and could well allow other Orthodox rabbis in the diaspora as well as in Israel to follow the logic of his arguments to justify a more accommodating approach to conversion in general.

Whether that will in fact be the case surely remains to be seen. Rabbi Amsalem’s opponents, however, have already made known their fierce disagreement with what he has written in Zera Yisrael. On May 20, 2010, Yated Ne’eman, the house organ of the United Torah Judaism party, ran on its front page a circular signed by the heads of the Ashkenazic Edah HaChareidis (ultra-Orthodox community) asserting that there was no halakhic justification whatsoever for Amsalem’s positions. The authors contended that only a complete acceptance of the yoke of the commandments would permit inclusion into the Jewish people. A “convert,” the circular maintained, who fails to make such an affirmation, regardless of any conversion ceremony performed under the aegis of any rabbi or rabbinic court, remains “a complete Gentile” (goy gamur) whether both parents are Gentile, or whether “the mother alone” is a non-Jew. Anyone who offers an opinion to the contrary is, by definition, incompetent (eino bar hora’ah klal). Indeed, such a man is “a complete heretic” (apikoros gamur). Although Rabbi Amsalem was not mentioned by name, an editorial, printed immediately under the declaration, reported that the gedolei yisrael (the great Torah Sages of our time) had expressed unalterable opposition to Amsalem’s claim that Jewish law possesses sufficient latitude to sanction conversion based on a “partial acceptance of the commandments.” Significantly, the newspaper refused to identify Amsalem as a rabbi, choosing instead to refer to him simply as “MK.”

Although it might seem that the argument between Amsalem and his Haredi opponents can be reduced to a political struggle over the mechanisms of conversion in Israel, I think that it actually represents much deeper disagreements about Judaism, Jewish peoplehood, and the Zionist enterprise. From the perspective of Amsalem’s Haredi opponents, we Jews are a people only by virtue of our Torah. Conversion to Judaism is, therefore, only possible when a Gentile embraces the duty thrust upon all Jews, forever, to observe all the 613 commandments that our tradition asserts were revealed by God. Anything less is unacceptable.

There is intellectual and historical precedence for this stance. As my teacher Jacob Katz pointed out in a brilliant chapter of his Out of the Ghetto, some of the 19th-century predecessors to contemporary Haredi authorities were tempted to rule that Jews who rejected the classical Jewish religious belief in revelation at Sinai along with halakhic practice were not Jews at all. They would have resolved their disputes with these heretics by defining them as beyond the borders of the Jewish people. However, the “quandary” these rabbis confronted was that Jewish law clearly states that one born of a Jewish mother is uncontrovertibly a Jew, and, as the Talmud states in tractate Sanhedrin, “A Jew, even when he sins, remains a Jew.” Katz entitled the chapter “Conservatives in a Quandary.” In the case of would-be converts, the same quandary does not exist, at least for present-day Haredi authorities.

His supposed heresy notwithstanding, Rabbi Amsalem, no less than the Haredim who savage him, affirms the belief that God revealed the Torah—both Written and Oral—to the Jewish people. Indeed, this is why Amsalem would never countenance the acceptance of conversions conducted under the supervision of Reform, Conservative, or Reconstructionist rabbis. But this should not obscure the fact that he has a substantively broader conception of Judaism than do his Haredi colleagues. For Amsalem, not only religion, but peoplehood is an indispensable component of Judaism. As the paradigmatic proselyte Ruth states to her mother-in-law Naomi when she embraces Judaism in the Book of Ruth, “Your people will be my people, your God my God.” This is what allows a traditionalist with Zionist commitments such as Amsalem to view the Russian immigrants, who have pledged their very lives and those of their children to share in Jewish fate and destiny as citizens of the Jewish state, as being of the seed of Israel.

In the course of his argument, Amsalem cites the lenient position that former Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi Isser Yehuda Unterman took in the 1970s on the conversion of Russian Israeli immigrants to Israel. Like Rabbi Unterman before him, he has a principled commitment to a Judaism that extends beyond religion alone. He encourages and tries to facilitate the conversion of non-Jews of Jewish ancestry to Judaism because his conception of the indivisibility of leum (nationality) and dat (religion) compels him to be inclusionary. His internalization of a Zionist ethos causes him to regard immigrants who constitute zera yisrael as part of the warp and woof of the Jewish people and he therefore holds that the need to convert them under religious auspices to Judaism is a necessity fully in keeping with Jewish law.

On the very first pages of Zera Yisrael, prior to the rabbinic approbations that praise the book, Amsalem reproduces a sermon by none other than Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, originally printed in the Shas party newspaper, Yom le-Yom five years ago, which argues for leniency and empathy on the part of rabbis in matters of conversion. Yosef cites the talmudic legend that the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob refused to accept the princess Timna “the sister of Lotan” as a Jew when she wanted to convert. This caused her to marry Eliphaz, and their union resulted in the birth of Amalek, the archetypal enemy of the Jewish people throughout history. To be sure, Yosef provided his own unique interpretation of this story. He claimed that Eliphaz actually performed a giyur reformi (Reform conversion), which was the cause of the calamitous birth of Amalek. Yosef prefaces this narrative with a rabbinic epigram that asserts, “The wise man wrote, ‘He sees clearly.’ What does this . . . mean?—That at the beginning of a matter, [a wise man] can foresee what will ultimately unfold.”

In Zera Yisrael and Mekor Yisrael, Rabbi Amsalem leaves no doubt as to what a clear-sighted view of conversion in Israel requires or where the present disastrous policies are leading. Though expelled from Shas, he has not retreated from politics. Instead, he has become the founder of a new party, Am Shalem (The Whole People). When Amsalem established this party, he wrote:

At a time like this, another type of leadership is required [in the Orthodox community] . . . Reality requires us … to struggle with the challenges that stand at the threshold of the State of Israel . . . The Am Shalem Movement promises to return sanity and moderation to the Haredi community.

Zera Yisrael and Mekor Yisrael surely provide the rabbinic basis for this aspiration. They are the intellectual fruits of his efforts to meet the challenges of our era while maintaining the heritage of religious Judaism. These sefarim should be welcomed, not least by those of us whose approbations would earn him no respect in the world he wants to change.

Suggested Reading

Culture and Education in the Diaspora

After 1948, Ben-Gurion strongly urged young American Jews to make aliyah. In 1951, Hayim Greenberg, head of the Jewish Agency's Department of Education and Culture, came to Jerusalem to argue for the dignity of Jewish life in the diaspora—in Yiddish.

The Bible’s Women in Medieval Ashkenaz

The Bible’s characters were everywhere in medieval Ashkenaz. Jews remembered them when they prayed, attended births and weddings, when they opened a haggada.

Politics and Anti-Politics

Michael Walzer asks new questions of the biblical text, the same sorts of questions we often ask of Locke or Voltaire.

EUGENE NADELMAN: A Tale of the 1980s in Verse

"Our tale's debut / Takes place in 1982 / When I, for one, if not exactly / A double of our leading guy / Was like him, bookish, awkward, shy." - Coming of age in iambic tetrameter.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In