Culture and Education in the Diaspora

Archives, Cincinnati, Ohio.)

In the years following the establishment of the State of Israel, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion repeatedly voiced his desire to see young American Jews immigrate to Israel. Ben-Gurion’s remarks led to a public dispute with Jacob Blaustein, president of the American Jewish Committee, which was eventually resolved through the “Blaustein-Ben-Gurion Agreement.” This agreement held that the option of aliyah “rests with the free discretion of each American Jew himself; it is entirely a matter of his own volition.” Memory of these developments was still fresh in 1951 when Hayim Greenberg delivered the address, from which the following excerpt is taken, to the Twenty-third World Zionist Congress in Jerusalem. Greenberg publicly challenged the Zionist movement and American Jews to rethink the nature of the relationship between Israel and America, as well as the place of the Jewish state in modern Jewish life. To drive home his point—and in an ironic twist given his role as head of the Jewish Agency’s Department of Education and Culture—he deliberately addressed the Zionist Congress in Yiddish.

Greenberg (1889-1953) was no stranger to controversy. After fleeing the Soviet Union in 1921, he spent the early 1920s in Berlin, where he co-edited the Zionist periodicals Ha-olam (The World) and Atideinu (Our Future) and came into close contact with Kurt Blumenfeld, Martin Buber, Chaim Arlosoroff, and other leading Jewish figures. By the time of his arrival in the United States in 1924, Greenberg had already established himself as an original thinker, a seasoned orator, and a gifted polemicist who was eloquent in four languages—Russian, Hebrew, Yiddish, and English. In New York, he assumed the editorship of Der yidisher kemfer (The Jewish Fighter), a high-minded Yiddish-language newspaper sponsored by the Poalei Zion party.

In 1932 he became founding editor of Jewish Frontier, the Labor Zionist movement’s English-language monthly. Greenberg’s broad interests and personal acquaintance with many leading Jewish and non-Jewish intellectuals in America, Europe, and Palestine made the journal a stimulating forum. It regularly featured essays by the Yishuv’s leadership and took special pride in presenting translations of modern Hebrew poetry and prose. In the 1930s Greenberg also conducted a fascinating public correspondence with Gandhi about non-violence, Zionism, and the plight of Europe’s Jews. Under Greenberg, Jewish Frontier was also the first Jewish journal to publish full accounts of the Holocaust in the summer of 1942 in English.

During World War II, Greenberg chaired the American Zionist Emergency Council executive committee and became the first director of the Department for Education and Culture in the Diaspora. He played a key role in winning the Latin American delegations’ crucial support for the United Nations resolution establishing the State of Israel in 1948.

The full transcript of Greenberg’s address originally appeared in Jewish Frontier (December 1951) XVIII: 12. This excerpt is from a larger work in progress Free Associations: Selected Essays of Hayim Greenberg—A Critical Edition, edited by Mark A. Raider. Professor Raider teaches modern Jewish history at the University of Cincinnati and is the author of The Emergence of American Zionism (NYU Press).

Over the two thousand years of our dispersion, we have had varying types of exile. Our sense of living in exile was not one and the same in all periods and in all countries. The acuteness and intensity of that feeling depended upon the particular environments and civilizations in which we lived . . . There were exiles that were worse, and others that were “better,” so to speak; exiles in which Jews sense their foreignness, helplessness, and state of outlawry with every fiber of their being, and other exiles in which they felt themselves partially rooted, or at least enjoyed the illusion of relative integration or adjustment.

Any country outside the dreamed-of Land of Israel was exile for the Jew, yet over a period of generations Jews came to regard some of the lands of their dispersion with a sort of “at-homeness” in an alien environment . . . Portugal and the Netherlands, Spain and Turkey in the 15th and 16th centuries were all, in principle, exiles. Yet it was not mere accident that refugees fled from the Iberian peninsula to the Low Countries or to the Ottoman Empire. One exile offered the Inquisition and autos-da-fé, the other, tolerance and relative hospitality . . . Even Israel itself was for many, many centuries, in essence, galut (exile). Wherever Jews live as a minority, where they are not politically or socially independent, where they rely on the good graces of the non-Jewish majority and are subject to the everyday pressures of its civilization and mode of life, such a place is galut.

In this respect, the United States today, and let us say, Iraq, are both “exiles” in the broad psycho-historical sense. But the concrete difference between the two is unspeakably great. Jews are compelled to flee from Iraq; no one drives them out of any part of America. If, in a general sense, exile may be conceived of symbolically as night, then there are some exiles of pitch-black night, and some where the night is moonlit . . .

A very substantial part of our people today resides in western countries with traditions of liberty, with a high order of civilization and technological development, with progressive economies creating sound opportunities for achieving in time modern standards of social justice. Those countries do not constitute for Jews the best of all possible worlds. But it would be wrong to say that Jews have not struck roots there, that they are totally unintegrated, or that they are faced with immediate threats to their existence. Jews have already attained there a degree of relative well-being economically, and though they are socially segregated to no small extent, still they are not regarded by the majority as aliens in the sense they are so branded in backward countries or countries experiencing the convulsions of a perverse nationalism . . .

If the time ever comes, as I believe it will, when considerable numbers of American Jews will go to live in Israel, they will do so not because America will have ejected them, but out of Israel’s attraction and inspiration, not in fear, but in love . . . The living Israel is, naturally, a far more effective stimulus for diaspora Jews in strengthening the will to maintain and cultivate their Jewish identity than is Zionism as a doctrine or a Weltanschauung. But the influence of present-day Israel can be a fertilizing factor for Jewish cultural life in the diaspora only on one condition: if the civilization of Israel should lean on certain, so to speak, extra-geographical elements in traditional Jewish culture, elements that have demonstrated their capacity to survive without the support and nourishment of a national soil.

I find it hard to express this point clearly, and I should like as far as possible to avoid using abstract or philosophical terms. In a sense one may say that the Jews have for many centuries—throughout the so-called galut period—lived more in the sphere of time than in the sphere of space, or perhaps more in the sphere of music than in the sphere of the plastic. Plastic art is quite inconceivable apart from space. A painting, a sculptural or architectural work, must occupy room or ground; a melody is spaceless . . . In a symbolic sense, Jewish culture was more of the historical and musical type than of the geographic and plastic type . . . the galut was perhaps the only example in history (at any rate, the most prominent example) of an ex-territorial civilization . . . Upon vast expanses of time and apparently out of nothing more than memories, strivings, and aspirations, our people created such grand structures as the Babylonian Talmud, the palaces of Kabbalah and Hasidism, the gardens of medieval [Jewish] philosophy and poetry, the self-discipline and inspirational ritualism of the Shulchan Arukh, the color and aroma of Sabbaths and holidays . . . We were without territory—yet possessed of clear and fixed boundaries that Jews devotedly guarded; without armies—and yet so much heroism; without a Temple—and yet so much sanctity; without a priesthood—and yet each Jew, in effect, a priest; without kingship—and yet with such unexcelled spiritual “sovereignty.”

Should we be ashamed of the exile? I am proud of it, and if galut was a calamity (who can pretend it was not?), I am proud of what we were able to perform in that calamity. Let others be ashamed of what they did to us in exile. We have every reason to consider our exilic past with heads proudly lifted . . . There will be no culture of tomorrow without a culture of yesterday and of the remoter past, unless we want to reconcile ourselves to a shallow pseudo-cultural style attuned to the local ethnography and narrow horizons of a small, irritably nationalistic state . . .

The fundamental objective of Jewish education in the diaspora is thus, in my view, not Zionism, in the specific or programmatic sense of the word, but Jewishness. Zionism should be the natural product of an organic education to Jewishness, the culmination, not the point of departure. Without such education, Zionism may be a doctrine, a convincing theory, a program, a plan, an undertaking of desperate urgency, an appeal to sentiment, a noble humanitarian enterprise, but not a profound creative experience. Hebrew is naturally a very, very important element in this sort of education, but I should prefer to use the term “Hebraism” rather than “Hebrew.” I use the word “Hebraism” here not in that polemical sense which in our time signifies an extreme language preference, a purely linguistic shibboleth, but in the way that I should use such a term, for example, as Hellenism.

I am far from being unappreciative of the importance of diffusing in the diaspora, let alone Israel itself, the knowledge of [modern] Hebrew . . . But may I be permitted to say that a Jew who can name all the plants in Israel in Hebrew, or call all the parts of a tractor or some other complicated machine by their correct designations (in new Hebrew coinages) possesses one qualification for useful service in the State of Israel. And who among us could fail to see in this not merely a technical or utilitarian but a cultural value as well? But if he does not know to their deepest sounding and in their context of spiritual tensions such Hebrew expressions as mitzvah (divine commandment), aveira (transgression), geulah (redemption), tikkun (repair), tumah (filthiness), tahara (ritual purity), yira (fear), ahava (love), tzedaka (righteousness), chesed (loving-kindness), mesirut nefesh (self-abnegation), kiddush Hashem (sanctification of the name), dvekut (cleaving to God), teshuvah (repentance), he cannot carry a part in that choir that gives voice, consciously or not, to what I have called “the Jewish melody.” Even so-called secular Jewish education in Israel and in the galut as well, if it is not to be drained of those powers that build a Jewish personality, must therefore be nourished from sources which are regarded, at least formally, as religious . . .

The Hebrew language must naturally occupy a central place in our whole folk pedagogy; there can be no “Hebraism” without a sound background in Hebrew. This does not mean, however, that in my opinion we should use in our educational processes Hebrew exclusively . . . Regardless of what fate may hold in store for us in the future, we shall have to use Yiddish . . . We shall also have to use non-Jewish languages, foreign to Jews as a collectivity, but native to or fully acquired by millions of individual Jews who live and grow spiritually through them . . . Such earnest, deep-plowing, cultural work permeated with Jewish individuality will in time, I am certain, bring forth a profounder Zionism, an appreciation of our historic drama, and an active will to play a role in it. It will lead even to halutzism which will draw its strength from the depths of Jewish being.

Only such an organic and wide-ranging educational program can create in the galut the inner resolution to identify oneself in full, in deed, with the grand process of Jewish revival . . .

In the final historical analysis, the State of Israel should be interested in the spiritual growth of diaspora Jewry no less than the Jews of the galut themselves. All Jewish roads—sooner or later, directly or indirectly, with landmarks or without them—lead to the same destination: to Eretz Israel.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Digression

A doctor walks into the examination room and tells his patient that the drugs aren’t working and there isn’t anything else to try . . .

King James: The Harold Bloom Version

There may be a thousand facets to the Torah, but does Harold Bloom simply misunderstand the King James Bible?

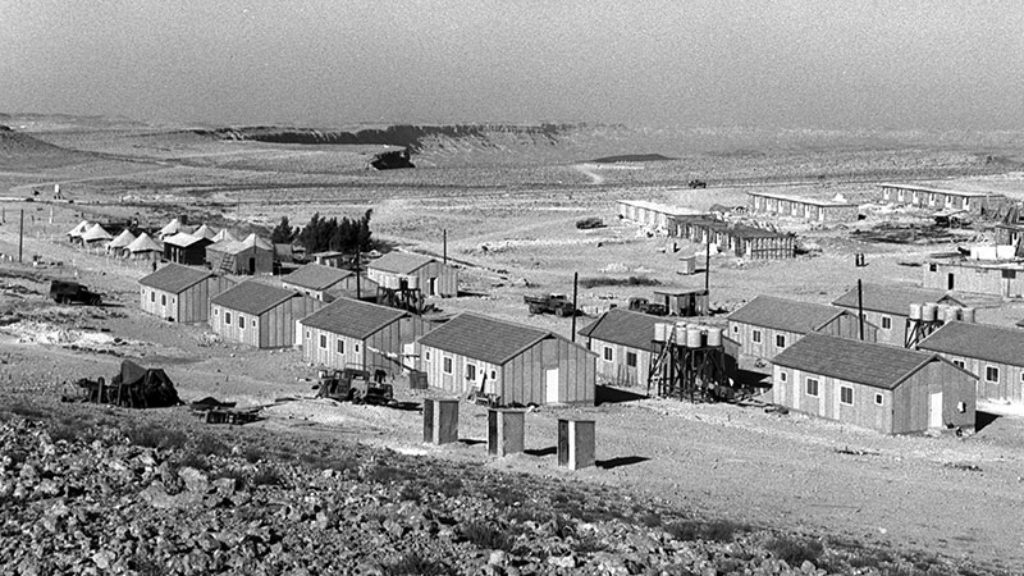

Seventy Years in the Desert

At the 1965 International Bible Contest, David Ben-Gurion posed some of the questions. He also asked two to the entire audience: “How many of you are ready to make aliyah to the Land of Israel?” And then, more specifically, “How many of you are ready to come and live with me in the Negev?”

Sadat in Jerusalem: Behind the Scenes

The outcome of Anwar Sadat’s 1977 visit to Israel was historic, but the backstage wrangling over protocol and Palestinian participation was also significant.

Andrew Tallis

Back in the late 1970's I spent a year and a half studying at Mahon Greenberg, which was then located in the Baka neighborhood of Jerusalem. The school was as a training center for North and South Americans to learn about Jewish history and study Hebrew in order to become teachers either in Israel or in other countries. A fitting salute to the man, I think.

SJLindenberg

I too was given shelter at Mahon Greenberg when I was at loose ends with no money while attending the Machon L'Madrechei in Katamon in 1964.

Sid Lindenberg