Politics and Anti-Politics

The Hebrew Bible is at once the most and the least familiar of books. We live in a world of its making, saturated by its language, concepts, and imagery. But precisely for this reason we find it remarkably difficult to read the biblical text with detachment.

Ever since the Enlightenment, the Bible has either been vindicated as the source of all virtue or anathematized as the sum of all fears. For Voltaire, it was the unedifying history of “the forgotten chiefs of an unhappy, barbarous land,” a depressing Bronze Age pageant of cruelty and unreason. Edward Gibbon agreed, explaining in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire that the biblical worldview embodied a bigoted rejection of “the cheerful devotion of the pagans” and the “universal toleration” made possible by good, old-fashioned polytheism. The Bible, in this view, is where it all started to go wrong.

For John Locke, in contrast, the Hebrew Bible provided nothing less than the indispensable foundation of Enlightened morality—it taught the revolutionary lesson that all human beings are “the workmanship of one omnipotent, and infinitely wise maker; all the servants of one sovereign master, sent into the world by his order, and about his business; they are his property, whose workmanship they are, made to last during his, not one another’s pleasure.” If you like this sort of thing, you will conclude, with Locke, that the Bible is where it all started to go right. If, like Nietzsche, you regard Locke’s claim as the degraded expression of a “slave morality” foisted upon mankind by “the Jews, that priestly people, which in the last resort was able to gain satisfaction from its enemies and conquerors only through a radical revaluation of their values, that is, through an act of the most deliberate revenge”—well, then not so much.

But nowhere has this sort of Manichaeism been more abundantly on display than in recent discussions of biblical political thought. Those loyal to the religious traditions to which the Hebrew Bible gave birth have tended to follow Locke and find within it the origins of everything we like about political modernity: democracy, the rule of law, separation of powers, social justice, the social contract, and human rights. Those unsympathetic to these religious traditions have instead sought to identify it as the source of everything we dislike about political modernity: collective punishment, genocide, racism, sexism, homophobia, and theocracy. For the first group, we might say, the Bible is just the covenant at Sinai; for the second, it is just the extermination of the Canaanite nations. The great virtue of Michael Walzer’s new book is that it manages to transcend these crude oppositions.

One of our most eminent political theorists, Walzer does not come to the Hebrew Bible to accuse or to defend, to attack or to praise. He is not interested in establishing the biblical pedigree of modern ideas, whether good or bad. He simply wants to discover how the authors of the Hebrew Bible thought about politics—to ask of the biblical text the same sorts of questions one can ask of, say, Locke or Voltaire.

This project grows out of Walzer’s previous work, much of which has focused to some degree on the intersection between politics and biblical religion. In his first book, The Revolution of the Saints, published close to half a century ago, he addressed the Puritan origins of what he called the “radical politics” of the English Revolution. Two decades later in Exodus and Revolution, he explored the political dimensions of the Exodus story and the liberationist uses to which it has been put throughout European and American history. This second work in particular was unmistakably preoccupied with the task of rescuing the Bible for the political Left—Walzer wished to challenge the Marxist piety that biblical religion was an engine of alienation and reaction and to demonstrate instead that it offered resources out of which one could fashion a respectably social-democratic politics.

But Walzer has since moved away from this recuperative approach to the political thought of the Bible. In the 1990s, he became co-editor, along with Israeli scholars Menachem Lorberbaum and Noam Zohar, of The Jewish Political Tradition, a projected four-volume anthology of Jewish political writings, with commentary by contemporary philosophers and scholars. In his own contributions to the two volumes published thus far, his primary aim has been to understand biblical and rabbinic texts on their own terms, to listen to what they have to say. His new book proceeds in very much the same spirit: as he puts it in the introduction, “I am not trying to find biblical proof-texts or precedents for my own politics . . . I won’t read the Bible as if it were a mirror in which to see myself.” His task is instead to listen to the voices of those who authored the biblical text and “to figure out as best I can what these voices are saying.”

Walzer’s account of what those biblical voices are saying is encapsulated in the claim that politics in the Hebrew Bible unfolds “in God’s shadow.” This phrase will remind some readers of a famous aphorism of Nietzsche’s from The Gay Science:

After Buddha was dead people showed his shadow for centuries afterwards in a cave,—an immense frightful shadow. God is dead:—but as the human race is constituted, there will perhaps be caves for millenniums yet, in which people will show his shadow.—And we—we have still to overcome his shadow!

For Nietzsche, to live “in God’s shadow” is to inhabit a world bereft of God, but one in which people nonetheless still think and act in ways that only make sense on the (officially) abandoned supposition that God exists. For Walzer, in contrast, to live “in God’s shadow” means almost exactly the reverse. It is to inhabit a world in which God is believed to be unremittingly present, as lawgiver, judge, and “man of war”; a world in which the law descends from on high and is understood to be both complete and unalterable. In such a world, Walzer argues, human agency is radically circumscribed, with the result that although “the biblical writers are engaged with politics,” they are “in an important sense . . . not very interested in politics.” They either embrace a form of overt “antipolitics,” stressing resignation in the face of providential deliverance or punishment, or else they carve out a (very) limited space for agency and innovation in a universe presided over by an omnipotent God.

To speak in these terms about what “the biblical writers” had to say about politics is already to make two basic, yet controversial assumptions. The first is that the text of the Hebrew Bible, including the Pentateuch, embodies a redaction of numerous shorter texts written by different authors across several centuries. The second is that, despite the composite and heterogeneous character of the resulting document, those who performed the final redaction believed that they had created a somewhat coherent whole—and that we must therefore read it, not as a collection of unrelated fragments haphazardly thrown together, but as a unity of some kind. Some readers will of course reject the first of these assumptions, while others will resist the second. Both premises, in my view, are straightforwardly correct, and it strikes me that Walzer is at his best when exploring the obvious tensions between them.

Walzer begins with a discussion of two different and competing understandings of the covenant itself: one according to which it is familial, tribal, and inherited (a promise to Abraham’s “seed”) and a second conception according to which it is voluntary and, in principle, “open to anyone prepared to accept its burdens.” Walzer identifies a “permanent, built-in tension between the birth model and the adherence model.” The first, on his account, “favors a politics of nativism and exclusion (as in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah),” while the second issues in “a politics of openness and welcome, proselytism and expansion (and even forced conversion, as in Hasmonean times, though adherence is supposed to be voluntary).”

Walzer’s second chapter explores perhaps the most fundamental feature of politics “in God’s shadow,” the notion that the law is perfect, complete, and fixed. Many other ancient societies possessed a corpus of law that was regarded as divine in origin, but these societies also left room for additional sources of non-divine law. The Torah, in contrast, is said to be complete: “Ye shall not add unto the word which I command you, neither shall ye diminish aught from it” (Deut. 4:2). There is no “legislation” in the biblical polity. One could only amend or supplement the laws by “restating” them—that is, by becoming a “secret legislator” and changing the content of what was revealed at Sinai. We accordingly find in the Bible three very different law codes, each of which is meant to be perfect and complete. This paradox of competing perfections, on Walzer’s account, is what “give[s] the Bible its special character”:

From a theological point of view the three codes are literally inexplicable—and that is why the differences between them are never acknowledged in the text . . . It is as if God presides over and therefore validates the different versions and also, necessarily, the disagreements they reflect. The disagreements can’t be openly recognized, but they also can’t be written out of the text. They make further exegesis imperative, since legal decisions and political and religious policies have to be justified in textual terms; and new exegesis gives rise in turn to new disagreements. And again, because new disagreements can’t be acknowledged, they can’t be resolved.

The result of all this, Walzer argues, was an unintended form of legal pluralism—”a written law that made possible those strange open-ended legal conversations that constitute the oral law of later Judaism.”

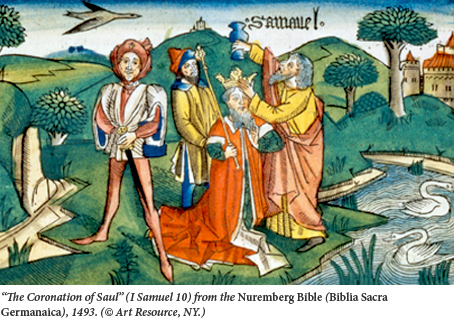

Walzer next turns his attention to the central political event in Israelite history, the establishment of monarchy described in I Samuel. He identifies three competing biblical understandings of kingship. The first regards human monarchy as a rejection of God’s sovereignty over Israel and, hence, as a sin. This view is powerfully present in the book of Samuel itself, where the people’s request for a king is said to be equivalent to a demand that God “should not reign over them.” In the book of Psalms, Walzer identifies what he calls the “high theory” of monarchy and attributes it to royal scribes writing at around the time of Solomon (the dating here is controversial). On this view, kingship is sacralized and kings themselves become God’s covenantal partners, “replac[ing] the people as the carriers of Israel’s history.” They also become the bearers of a promise of eternal succession, ensuring that future Israelites “would wait for the miraculous return of the heir of David’s house.” The third understanding of biblical monarchy, found in Deuteronomy, is something of a mean between these extremes. It regards kingship as acceptable and even desirable for various practical reasons, but offers a radically circumscribed account of kingly powers. (Following the consensus among biblical scholars, Walzer regards Deuteronomy 17 as a later gloss on I Samuel 8.) Here at last, on Walzer’s account, we have something approaching “normal politics”: a sort of pragmatic constitutional monarchy that interposes itself between the “antipolitics” of the kingdom of God and the messianic enthusiasms of sacralized human kingship.

The next three chapters address the role of prophets, focusing in particular on their embrace of political quietism: “In return and rest shall ye be saved; in quietness and in confidence shall be your strength” (Isaiah 30:15). But Walzer is perhaps most suggestive when discussing the emergence of a new and broader prophetic audience. In defiance of the “high theory of monarchy,” the later prophets (from Amos onwards) began addressing themselves to the nation as a whole; it is the people, and not simply the king, who must return to God and repent. They will be punished for their own sins and rewarded for their own faithfulness. But this vision of divine justice continued to treat Israel as a single body, a transgenerational collective agent. It was perfectly consistent with the famous claim in the Decalogue that God “visits the iniquities of the fathers upon the children to the third and fourth generations” (Ex. 20:5). In the writings of the great exilic prophets, however, we find the first intimations of a very different argument. Each individual Israelite, Ezekiel tells us, should only suffer for his own individual sins: “What do you people mean by quoting this proverb about the land of Israel: ‘The parents eat sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge’? As surely as I live, declares the Sovereign Lord, you will no longer quote this proverb in Israel . . . The one who sins is the one who will die.” (Ez. 18:1–4, though elsewhere Ezekiel expresses a very different view.)

Walzer recognizes this as a momentous departure from earlier biblical ideas about collective responsibility, and he attributes it to the exilic fracturing of the national political community. In the absence of “kings, priests, and judges, authority structures and communal decisions” all that remained was individual responsibility. He might also have related it to a second, simultaneous development. After all, it is in Ezekiel 37 that we find the first imagined general resurrection of the dead. As Jon D. Levenson has recently argued, the understanding of personality in the Pentateuch is corporate and collective in character. God’s promise of immortality is given to Israel as an organic whole and it is vindicated through the miraculous overcoming of infertility (for example, the birth of Isaac to a woman “old and stricken with age”) and through redemptive events such as the deliverance from Egypt. The death of a righteous man such as Abraham is, on this view, no reproach against the justice of God, for Abraham is “gathered to his people” and his seed endures forever. Abraham just is his family. Once this collective, organicist conception of personality begins to fray, however, a severe problem of theodicy arises. If it is wrong to punish me for the sins of my father, it is likewise wrong to pay my reward to my son. God’s promise that the righteous man “will surely live” (Ez. 18:9) must now be honored to persons as such—and, given the ostentatious fact of the death of the righteous, it is not difficult to see why the insistence upon a future life became so urgent. This is a crucial chapter in the story of how biblical indifference to personal immortality eventually gave way to the rabbinic maxim that “he who says that the resurrection of the dead is not in the Torah” is as much of a heretic as one who says “that the Torah is not from Heaven.”

Walzer concludes his commentary with chapters on the post-exilic priestly kingdom, the political perspective of Wisdom literature (Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the non-canonical Ben Sira), messianism, and the enigmatic, protean figure of the biblical “elder.” The analysis throughout is rich and suggestive—indeed, there is scarcely a single page of Walzer’s book that does not contain a novel, incisive, and provocative observation about passages that have been studied without interruption for millennia. He notes, for example, that Ezekiel describes himself as prophesying “as I sat in my house, and the elders of Judah sat before me” (Ez. 8:1). In this small detail, Walzer detects a “symbol of statelessness”—a crucial and poignant reflection on the degree to which exile had supplanted politics among the Israelites. The earlier prophets had offered their visions in public:

Amos went to the shrine of Beth-el to prophesy; Isaiah went to the palace of the king or the gates of the city; Jeremiah spoke in the temple courtyard. But in Babylonia, the elders come to Ezekiel’s house.

In exile there are no public spaces; “prophecy,” in Walzer’s fine phrase, “has retreated to the living room.” Passages such as this make In God’s Shadow a delight to read.

To the extent that the book has a weakness, it has to do with the overall framing of the discussion, rather than with the close readings themselves. Walzer claims in the introduction that “there is no political theory in the Bible. Political theory is a Greek invention.” Is this right? If by “theory” we mean a formal and explicit argument connecting premises to conclusions by way of a syllogism, then of course there is no theory-political or otherwise—in the Hebrew Bible. But, in this definition, there is also no political theory in Thucydides’ History, the speeches of Demosthenes, Machiavelli’s Prince, or More’s Utopia. If, in contrast, we define a “theory” simply as a set of interlocking and mutually reinforcing claims that, together, underwrite a series of normative conclusions, then it seems to me that the Bible is full of theories. (Walzer himself, after all, freely discusses something called “the high theory” of biblical monarchy.)

One important such theory goes like this: God redeemed the Israelites from Egyptian bondage and therefore owns them (Ex. 6:2–8); they are to be his servants (literally, “slaves”) rather than anyone else’s: “For they are My servants, whom I freed from the land of Egypt; they may not give themselves over into servitude” (Lev. 25:42). It follows that Israelites should not take each other as slaves (although they may certainly enslave non-Israelites, who do not belong to God in the same juridical sense), and, since landlessness is equivalent to the condition of servitude (Gen. 47:19), it follows further that the land of Canaan should be distributed equally and inalienably among tribes and families so as to ensure the independence of each Israelite household in perpetuity (Lev. 25:10–24)—and that debts should be forgiven, so that debtors are not required to enslave themselves in the event that they cannot pay their creditors (Deut. 15:1–3).

Suppose we agree that this is indeed a theory. Is it also a political theory? Once again, Walzer would seem to want to answer “no.” A political theory, in his account, addresses itself to “an autonomous or distinct political realm,” to “an activity called politics,” or to “a status resembling Greek citizenship.” It involves a “recognition of political space, an agora or a forum, where people congregate to argue about and decide on the policies of the community,” and must apparently make room for “political mobilization” and a “popular tradition of protest.” Most importantly, the sphere of life that it theorizes is to be distinguished from the “religious,” the “legal,” the “moral,” and the “social.” The worry, of course, is that this way of putting things amounts to loading the dice. Walzer has sketched a quite specific understanding of the “political”—one of extremely recent vintage. By these lights, it is certainly true that the biblical theory I just outlined cannot be called “political,” but, then again, neither can virtually any other theory that precedes Max Weber.

The distinction between the “secular” and the “religious” that Walzer so frequently deploys would have been unintelligible to the authors of the Bible (needless to say, biblical Hebrew has no equivalent terms). To return to Edward Gibbon, it emerged out of the contest between the “Christian commonwealth,” or visible church, and the civil order during Rome’s final centuries. We should therefore be wary of describing the Bible with Walzer as “above all a religious book” and Israel as “a religious culture,” and of characterizing “the powerful idea of divine sovereignty” as part of that “religious culture,” rather than as part of a “political theory.” To say, as Walzer does, that in the biblical worldview “every political regime was potentially in competition with the rule of God” is to miss the fundamental point that, for the biblical writers, the rule of God was a political regime.

Something quite similar might be said about the proposed distinction between the “political” and the “social.” Although Walzer greatly admires what he calls the “social ethic” of the Bible, and of the prophets in particular, he regards it as fundamentally unrelated to any recognizably “political” commitments. Its various instantiations—from “the slavery laws” to “the reiterated injunction to care for the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow”—are simply expressions of social solidarity, grounded in the memory of Egyptian bondage and “entailed by the idea of justice.” It is this perspective that leads Walzer to omit any mention of what many have regarded as the central “constitutional” feature of the biblical polity: the equal division of lands and the institution of the Jubilee. The notion that such a measure is not “political” in character seems slightly counterintuitive. (Would we say that Plato’s views on the distribution of property were not part of his political theory?) The biblical land laws were not abstractly “social” or “humanitarian”; they were the institutional elaborations of Israel’s distinctive servitude to God, ensuring that every Israelite would serve Him and only Him. They also reflected the peculiar character of property rights as understood in the Bible, according to which God is universal landlord—”For the land is Mine; you are but strangers resident with Me” (Lev. 25:23)—and human beings simply hold leases to bits of the world “on good behavior.” If we resist the temptation to project modern categories backwards onto the biblical text, we might begin to discover within it a richer, if quite foreign, conception of “the political.”

Nonetheless Walzer has written a lucid, probing, and broad-minded study that will enrich each reader’s understanding of the great architectonic text of Western civilization. We are in his debt.

Suggested Reading

The Life of the Flying Aperçu

Dickstein’s story is not a narrative of apostasy and rebellion; belief and doctrine play a minor role.

If This Is a Man

Primo Levi often claimed that he was first and foremost a chemist and not a professional writer, but anyone who reads him with care will be moved by the sober lucidity, subtlety, concision, and analytical power of his prose.

Historical Agency

Among the many papers discovered in the Cairo Geniza are documents, including letters between Yeshua ben Ismail of Alexandria and Khalluf ben Musa in Qayrawan, in present-day Tunisia. The papers showing disintegration of their partnership shine a light on how a particular kind of business agreement affected the composition of a halakhic guidebook still widely consulted to this day.

A Novel of Unbelief

Religion, faith, and the search for tenure at Harvard underpin a comic novel by Rebecca Newberger Goldstein.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In