The Statesman

As much as at any time in the past, Israel is today beset by a sense of crisis. Anxiety about the future has bred more and more nostalgia for what seems to have been lost. It is a ripe moment for books that focus on the values that inspired the creation of the state in the first place, and it is very fitting that Shimon Peres should have produced one. Currently the president of Israel, but once one of David Ben-Gurion’s most prominent protégés, Peres addresses the present crisis by holding up Ben-Gurion as an example of “the sort of leadership that the country so desperately needs.” This biography is therefore not merely an account of Ben-Gurion’s life and times, but also Peres’ personal reflections about leadership, Jewish and Zionist history, and, to a certain degree, an assessment of his own political career in light of what he learned from his mentor. It is no doubt intended to inspire future leaders to follow in Ben-Gurion’s footsteps.

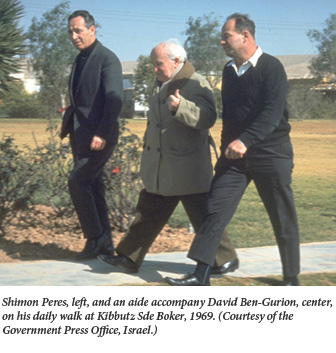

In a sense, there is no one more qualified than Peres to write such a book. Having met Ben-Gurion when he was still a youth movement leader, Peres quickly established himself as one of Ben-Gurion’s closest aides and a key member of his inner circle. An exceptionally competent judge of character, Ben-Gurion appointed Peres to the vital position of director general of the Ministry of Defense when he was only 29 years old, and put him in charge of weapon acquisitions and military-strategic alliances, a responsibility he maintained throughout the 1950s. His acquaintance with Ben-Gurion was therefore personal and intimate. Now, after a long and distinguished—if often very controversial—career, President Peres, Israel’s elder statesman par excellence, is ideally situated to serve as a link between the founding generation and the present one.

In a sense, there is no one more qualified than Peres to write such a book. Having met Ben-Gurion when he was still a youth movement leader, Peres quickly established himself as one of Ben-Gurion’s closest aides and a key member of his inner circle. An exceptionally competent judge of character, Ben-Gurion appointed Peres to the vital position of director general of the Ministry of Defense when he was only 29 years old, and put him in charge of weapon acquisitions and military-strategic alliances, a responsibility he maintained throughout the 1950s. His acquaintance with Ben-Gurion was therefore personal and intimate. Now, after a long and distinguished—if often very controversial—career, President Peres, Israel’s elder statesman par excellence, is ideally situated to serve as a link between the founding generation and the present one.

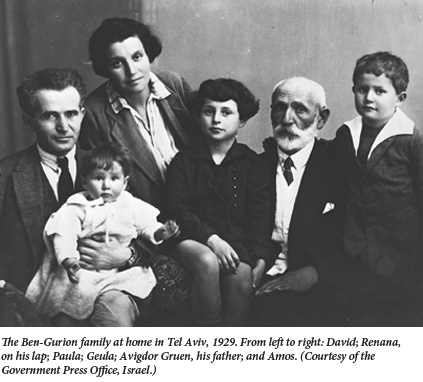

Ben-Gurion: A Political Life traces its subject’s life from his birth in Poland in 1886, through his arrival in Eretz Yisrael in 1906 and subsequent rise in Labor Zionist circles; his emergence as leader of the Zionist enterprise, in which capacity he proclaimed the independence of the State of Israel in 1948; his military-strategic leadership during the War of Independence and during the first years of statehood; his retirement to Kibbutz Sdeh Boker deep in the Negev desert; his falling out with his party’s rank and file amidst bitter political controversy; and finally, his death in 1973. The narrative authored by Peres is occasionally interrupted by dialogues with Peres’ collaborator, journalist David Landau. These interruptions usually occur when Peres approaches a touchy subject, such as allegations that the Yishuv under Ben-Gurion’s leadership did not do enough to rescue European Jewry during the Holocaust, Ben-Gurion’s relationship with the Orthodox sectors, or what was regarded by many as his autocratic style of leadership. This device allows Peres to show, without deviating from his unflinching loyalty to his mentor, that he is aware of criticisms of Ben-Gurion’s conduct, leaving it to Landau to play the role of devil’s advocate.

The portrait of Ben-Gurion that emerges is one of a man single-mindedly focused on the establishment of the state and securing its existence. For him, “everything else was secondary. He was like a rock, and he never moved from his fixed purpose.” In Peres’ account, it was Ben-Gurion’s capacity to make decisions that rendered him unique not only in the history of the Zionist movement and Israeli politics, but in Jewish history as a whole. “Throughout his life Ben-Gurion thought the Jewish people lacked statesmen, and that this was a key reason for our long history of disasters. We are a nation, he often said, with a wealth of prophets but a dearth of statesmen.”

What Peres himself is most interested in conveying is Ben-Gurion’s greatness as reflected in his most momentous decisions. These include, according to Peres, his acceptance of the partition of Eretz Yisrael into a Jewish and an Arab state, his proclamation of statehood as soon as he felt that conditions were ripe, and the immediate opening of the gates of the newborn state to all Jewish refugees who wished to settle in it.

Acceptance of partition in 1947 “represented the acme of leadership. Ben-Gurion’s fortitude and certitude in facing opposition from the right and the left were all the more impressive because, obviously, he too would have liked to see the Jewish state set up in all of Eretz Yisrael . . . But courageous decision making means the ability to take a less-than-perfect decision and stick with it.” Ben-Gurion pushed ahead with the declaration of statehood in May 1948 despite Secretary of State George Marshall’s “warning that the Yishuv might not survive the anticipated Arab attack.” The prospect of absorbing hundreds of thousands of immigrants into the financially strapped state at the very moment of its birth prompted fears of bankruptcy and was perceived by many to constitute a threat to democracy, since the newcomers mostly lacked any training in self-government. “Some officials wanted a policy of ‘selective aliyah,’ with priority given to younger and more productive people.” Ben-Gurion, however, “would not hear of any reservations or any selectivity.”

Acceptance of partition in 1947 “represented the acme of leadership. Ben-Gurion’s fortitude and certitude in facing opposition from the right and the left were all the more impressive because, obviously, he too would have liked to see the Jewish state set up in all of Eretz Yisrael . . . But courageous decision making means the ability to take a less-than-perfect decision and stick with it.” Ben-Gurion pushed ahead with the declaration of statehood in May 1948 despite Secretary of State George Marshall’s “warning that the Yishuv might not survive the anticipated Arab attack.” The prospect of absorbing hundreds of thousands of immigrants into the financially strapped state at the very moment of its birth prompted fears of bankruptcy and was perceived by many to constitute a threat to democracy, since the newcomers mostly lacked any training in self-government. “Some officials wanted a policy of ‘selective aliyah,’ with priority given to younger and more productive people.” Ben-Gurion, however, “would not hear of any reservations or any selectivity.”

It takes a very special type of individual to be able to face the kind of obstacles that Ben-Gurion confronted and nonetheless follow through with what one believes is right. Thanks to his longtime proximity to his subject, Peres can draw on his personal memories to elucidate just what kind of a man Ben-Gurion was and how he behaved. Only from Shimon Peres could one hear, for instance, the story of Ben-Gurion at work in his office in Ramat Gan during the first month of the War of Independence on the day that it was bombed and strafed from the air.

Ben-Gurion himself refused to take shelter during the air raid. I remember him sitting impassively at his desk writing. When a guard outside was hit by shrapnel, Nehemia Argov, his military aide, and I ran out with a stretcher. Ben-Gurion got up, but only to lend a hand carrying the wounded man to an ambulance. Then he returned to his writing.

The subjective point of view from which the book was written has, however, some drawbacks. Peres goes out of his way, for instance, to blame his rival, Likud premier Yitzhak Shamir, for ruining in the 1980s any chance of implementing what has been known as the “Jordanian Option,” the possibility of transferring rule over the West Bank Palestinians to the Hashemite kingdom. It is regrettable that Peres mentions this episode at all, since it really does not bear on the question of Ben-Gurion’s leadership and looks unnecessarily self-serving.

The Likud is of course an outgrowth of the Revisionist Party, founded and headed by Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, whose momentous struggle with Ben-Gurion in the 1930s receives a considerable amount of attention in Ben-Gurion: A Political Life. But Peres does not really clarify what lay at the root of the two men’s rivalry. All that he tells us is that Jabotinsky promoted “a maximalist message” in an age of extremism and that Ben-Gurion likened his movement to fascism. Peres does acknowledge that in spite of this “a remarkable degree of agreement seemed to exist” between the two men “on many key issues,” but he doesn’t say what they were. It would have been helpful if he had explained that Ben-Gurion and Jabotinsky were, for one thing, in fundamental accord on the imperative of attaining statehood, something to which the latter was if anything even more single-mindedly devoted than the former.

Peres’ cursory treatment of Jabotinsky is a good example of how the book’s brevity impairs its effectiveness. Well-informed readers are likely to consider the book’s narrative sketchy and insufficient, while readers newer to the subject are likely to find it difficult to follow. No one is going to emerge from a reading of this book with a better understanding of Ben-Gurion’s intricate relationship with longtime Zionist leader and first President of Israel, Chaim Weizmann, or the reasons why members of Ben-Gurion’s own party, Mapai, ultimately forced his ouster.

Peres’ cursory treatment of Jabotinsky is a good example of how the book’s brevity impairs its effectiveness. Well-informed readers are likely to consider the book’s narrative sketchy and insufficient, while readers newer to the subject are likely to find it difficult to follow. No one is going to emerge from a reading of this book with a better understanding of Ben-Gurion’s intricate relationship with longtime Zionist leader and first President of Israel, Chaim Weizmann, or the reasons why members of Ben-Gurion’s own party, Mapai, ultimately forced his ouster.

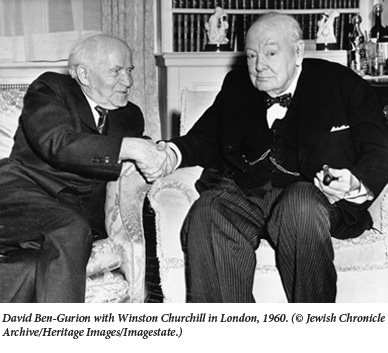

On the whole, Peres does a much better job of describing Ben-Gurion’s deeds than he does of explaining how Ben-Gurion became the kind of person that he was. What we do learn from him is that Ben-Gurion admired Winston Churchill for his leadership of Britain during World War II, and—embarrassingly, yet understandably-Vladimir Lenin for his resoluteness. In the intellectual realm, we learn that Ben-Gurion read amazingly widely, from Greek philosophy to French linguistics and Zen Buddhism and immersed himself in the Hebrew Bible. Unfortunately, Peres does not tell us very much about how his prodigious reading and correspondence with an array of intellectual leaders affected him and played a role in shaping what the book’s subtitle designates as Ben-Gurion’s “political life.”

This omission reminds us of the gulf that exists between the founding generation of “fathers” and that of “the sons.” The fathers, Ben-Gurion among them, were revolutionaries and not merely because they had read Lenin. They had lost the faith of their own fathers and sought to transform what they perceived to be studious and weak Jews into the very opposite. They emphasized action over thought. Nonetheless, they still had a millennia—long tradition of Jewish learning behind them. The sons, however, were born into a virtual vacuum. And there is reason to believe that it is precisely the intellectual gulf that separates the sons—and now, the grandsons—from the fathers that has induced in Israel such strong nostalgia for what has been lost. Ben-Gurion, more than any other Israeli prime minister, invested his energies in the battle for the soul of the state. In other words, it was not just his actions but also his thoughts that made him tower over all those who followed him in office. This short biography thus serves as a timely reminder that a titan once walked this land. One hopes it will inspire readers to delve into the voluminous literature that provides a more thorough account of the deepest thoughts and finest hours of the man who could be considered Israel’s principal founding father.

Suggested Reading

Us or Them

It all started with a tweet: “Curious about your whiteness? Come to our meeting.” Edelman was curious.

Remembering Walter Laqueur

Like the man himself, the pieces Laqueur wrote for JRB contain enormous insight and breadth.

Jews of Dune

In Chapterhouse: Dune, the sixth book in the Dune series and the last Herbert wrote before his death, the Jews show up.

Lilith and the Knight

Demons, dragons, and a “Tel Aviv hipster in King Arthur’s Court.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In