Thinking About Revolution and Democracy in the Middle East: A Symposium

Beginning with the protests in Tunisia that toppled the regime of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in January of this year, revolution has spread across North Africa and the Middle East with such velocity that predicting exactly what will happen next is probably a fool’s errand. Elsewhere in this issue, our authors and reviewers discuss what these events may mean for Israel, particularly but not only in its relations with a post-Mubarak Egypt. Here, we have asked seven writers to return to their bookshelves and tell us what books, authors, and arguments they find helpful in thinking through the causes and implications of these surprising events.

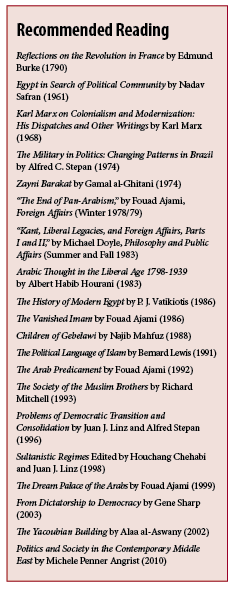

Our symposiasts are an extraordinarily distinguished and eclectic group of scholars, diplomats, theorists, and activists. Having reached across the board for help, we weren’t surprised when their answers were all over the map. Edmund Burke’s name came up, but so did that of Karl Marx and the much more recent theorist Michael Doyle. We were directed to the works of venerable students of Middle Eastern affairs like Bernard Lewis and Fouad Ajami, but also to less famous scholars like Houchang Chehabi and Juan J. Linz, the editors of the wonderfully titled Sultanistic Regimes. There are novels on our reading list too, including those of Egyptian writers Najib Mahfuz, Alaa al-Aswany, and Gamal al-Ghithani. Finally, for the extraordinary reader who has already read everything mentioned, there is one to which you can still look forward: Steven Cook’s soon-to-be-published history of Egypt.

-The Editors, March 29, 2011

The Middle Eastern Dialectic

BY SHLOMO AVINERI

Writing in the New York Daily Tribune in 1853, Karl Marx described contemporary India as a society “contaminated by distinctions of caste and by slavery,” immersed in “a brutalizing worship of nature” and based on “an undignified, stagnatory, and vegetative life . . . which rendered murder itself a religious rite in Hindostan.” Such stagnant “Oriental despotism” (to use Marx’s term) did not possess internal mechanisms of change. It was British rule, on the other hand, that introduced modernity—and change—into this society: a railway system unifying the subcontinent, a rational bureaucracy, a local market economy becoming part of a global economy. He concluded:

[Because] mankind cannot fulfill its destiny without a fundamental revolution in the social state of Asia . . . whatever may have been the crimes of England, she was the unconscious tool of history in bringing about this revolution.

This historical dialectic—what Hegel called the “Cunning of Reason”—may not be exactly a socialist version of “the white man’s burden,” but it comes close. Such ideas have accompanied modernizers in the Arab world, too, since Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt. Muhammad Ali’s attempts at modernization in Egypt, as well as a long list of Ottoman Tanzimat reforms were all inspired by variations on the Enlightenment model in which future redemption and prosperity reside in the Orient adopting the Occidental developmental route. Edward Said may have branded this as racist European “Orientalism,” but it was an idea adopted, willingly and enthusiastically, by many Middle Eastern (and Asian and African) intellectuals and political leaders who contrasted their own impoverished countries and authoritarian forms of government (all preceding Western colonial expansion) with the prosperity and freedom of the West. In his The Arab Predicament, Fouad Ajami follows, among other themes, the infatuation of the Arab intelligentsia with 19th– and 20th-century European ideas. There has not been a Western ideology, movement, or institution that has not found its followers in the Arab world. In the 1920s, it was the European model of the nation-state, anchored in liberal constitutionalism; in the 1930s, varieties of fascism; in the 1950s, different strands of socialism, some inspired by the Soviet Union. Pan-Arabism, Arab socialism—all were fashioned on European models.

The Arab tragedy was that all these attempts failed dismally. Their failure was compounded by the fact that the adoption of each of these models was out of touch with local social conditions and religious belief systems, and the attempt to foist European models on Arab society created distorted realities—sometimes caricatures, in some cases frightening monstrosities. In the 1920s-30s, liberal constitutionalism became in Egypt (as well as in Syria and Iraq) a cloak for the rule of the traditional landowning classes, the effendis. Nasser’s “Arab socialism” became the disguise for an attempt at Egyptian hegemony under a military junta; and Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party rule in Iraq (and to a lesser degree its Syrian variant under the two Assads) combined, as Bernard Lewis suggested, the worst amalgam of fascism and Soviet-style communism.

One consequence of this failure of all European-derived models was to open the door to Islamism. Far from being an aggressive attempt at world dominion, as Islamic fundamentalism is sometimes presented, it is much more a sign of defeat. After having failed in all attempts to implant foreign models, what could be more enticing and captivating than an inward-looking “return” to an idealized, and sometimes totally invented tradition of pristine Islam, before the region became contaminated by western ideas?

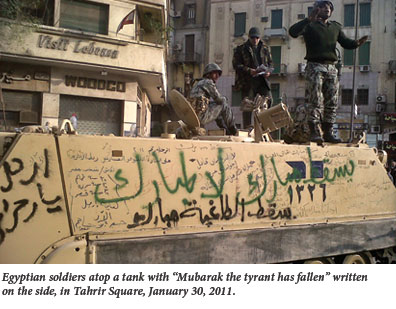

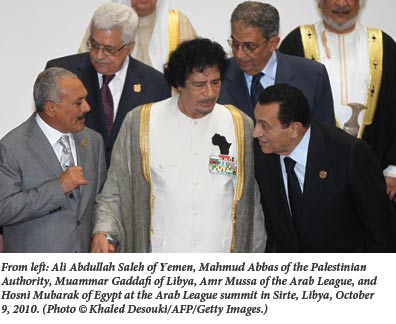

By contrast, what is happening now in the Arab countries is a genuine novelty. Spontaneous mass demonstrations have brought about the fall of authoritarian regimes in Tunisia and Egypt and continue to pressure the rulers in other countries. Nothing like this has ever happened before in the Arab world, which had known numerous military coups d’état and putsches, but never a popular revolution. While successful in bringing down the relatively mild autocracies of Ben Ali and Mubarak, this popular wave has yet to prove that it can bring down the harsh systems of Gaddafi or Assad, let alone the traditional monarchies, which seem to possess a sort of traditional legitimacy the republican regimes (in reality, military juntas wearing tailored suites) had never enjoyed.

The battle cry on Tahrir was—and is—a Western one: “democracy.” And it is aided by modern—Western—means of mass communication and social networking. Its success cannot be denied. However, the question remains whether it will be equally successful in establishing stable democratic regimes. This depends on concrete conditions, not imported ideas, and these will vary from country to country. Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan have shown in their Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation how much successful transitions depend on local conditions: the existence of elements of a civil society, traditions of pluralism and individualism, a relative autonomy of a variety of mediating institutions, as well as the historical role of religion.

Linz and Stepan’s book takes in a variety of countries and societies—from Eastern Europe to Spain and Portugal and Latin America. Even the more limited post-Communist experience shows a great diversity—from successful transitions in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary, to neo-authoritarianism in Russia and the “sultanistic” regimes of the former Central Asian Soviet republics.

Which will it be, for example, in Egypt? Will the army, which has ruled the country for almost 60 years, give up its enormous political power and economic clout? Will democratic parties emerge in a landscape in which the best-organized social movement is the Muslim Brotherhood? And what will eventually happen in Libya?

“How beautiful was the Republic—under the Monarchy?” went a saying popular during the turmoil of the French Revolution. In the Arab world, the jury is still out.

Shlomo Avineri, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, was member of international observer missions to the first post-communist elections in several Eastern European countries.

Reflections on the Revolution in Egypt

BY AMR BARGISI

I picked up Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France after the Tunisian uprising and have been re-reading it ever since. Like the Arab uprisings of today, the French Revolution initially sparked much enthusiasm and little skepticism. Although as an Egyptian, I hold no brief for Mubarak or any of the other Arab tyrants, Burke’s attack on “the spirit of innovation,” the desire to break with all things past and establish an entirely new social and political order, still resonates.

What the Western media has been calling the “secular opposition” consists mostly of naïve pseudo-activists alongside many opportunists, mediocre thinkers, and madmen. This “youth revolution” with its incoherent mix of hopes, demands, and grievances, and its insistence on the stark opposition between the young and the old scares me, my own youth notwithstanding. When I visited Tahrir Square I thought of Burke: “but what is liberty without wisdom, and without virtue? It is the greatest of all possible evils; for it is folly, vice, and madness, without tuition or restraint.”

Not that a people should endure the injustice of a despot for the sake of preserving stability and tradition. Burke acknowledges the right of people to dismiss their ruler by force, but only if all other means have been exhausted. This wasn’t really the case in Tunisia, and even less so in Egypt. Dozens of former officials and business men are now facing house arrest, confiscation of property, or imprisonment without due process, and calls for an even deeper purge are filling newspaper pages and TV airtime.

“Days of rage” may topple a dictator—in Tunisia and here in Egypt, at least, they have—but they are unlikely to produce democracy, and neither is Egypt’s more likely path. The constitutional reform that just passed is almost certainly a win for the military dictatorship that Mubarak led for so long, with perhaps a few seats at the table for the Muslim Brotherhood and others. In short, we are probably closer to Nasser’s 1952 Free Officers Coup than we are to 1776. I wish that I thought otherwise.

What can we Egyptians do? We do not have sufficient foundations for a truly liberal democratic regime, and these can only be laid down through a slow, patient work of building civil institutions in a stable atmosphere. As Burke argues, democracy is not to be found or created in an undifferentiated mob but in the small associations of society:

To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections. It is the first link in the series by which we proceed towards a love to our country, and to mankind. The interest of that portion of social arrangement is a trust in the hands of all those who compose it; and as none but bad men would justify it in abuse, none but traitors would barter it away for their own personal advantage.

Reflections on the Revolution in France is an antidote to the peculiar complacency that comes with utopian aspirations. In it, Burke echoed long forgotten classical voices to remind his fellowmen that the “Tyranny of Many” is even worse than the “Tyranny of One.” Perhaps it is not yet too late for the revolutionaries in my country and elsewhere in the region to learn this lesson.

Amr Bargisi is the Director of Programs at the Egyptian Union of Liberal Youth.

Why Now?

BY EVA BELLIN

Trotsky famously said, “Revolution is impossible until it is inevitable.” No one expects revolution to occur, even when the motives are obvious and pressing. Numerous factors—structural, ideological, sociological—stand in the way of successful uprising. Until they don’t.

Readers looking for a way into the politics of the region might begin with Michele Penner Angrist’s excellent edited volume, Politics and Society in the Contemporary Middle East, published just a few months ago. But while such discussions identify the repression, corruption, and economic hardship that motivated the uprisings, they don’t quite explain why they are happening now. After all, there have been legitimate grievances on these scores for decades. Furthermore, the wave of protest got its start in, of all places, Tunisia—a country whose experience of these afflictions has been modest when compared to, say, the pervasive poverty of Egypt or the kleptocracy of Saudi Arabia.

So how to account for the when and the where? It is no surprise that the unrest got started in the republics, not the monarchies, and in the personalistic, “patrimonial” republics first. In such regimes, including the recently deposed governments of Tunisia and Egypt, rule is concentrated in one person whose hold on power is secured through a mix of patronage and coercion. Should the regime fail to deliver sustenance or security, the leader is the natural focus of popular anger. Since leaders such as Ben Ali and Mubarak have neither the traditional legitimacy of a monarch nor the base of support that comes with effective party organization, they are particularly vulnerable. Even more important, these leaders are vulnerable to abandonment by the coercive apparatus (especially the military), which may decide it is easier to toss over a single leader than to try to defend an inept system. So Ben Ali and Mubarak were always more at risk than Jordan’s Abdullah or Morocco’s Muhammed VI. The experiences of Trujilo, Batista, Somoza, Duvalier, and Pahlavi bear this out, as was shown in a now-classic collection of case studies edited by Houchang Chehabi and Juan J. Linz called Sultanistic Regimes.

The character of the military is just as important. Protests snowball when the protesters are persuaded that the military will not shoot. And regime elites will flee when the military abandons their defense. But what determines whether the military will defect? At heart is the issue of whether the military is personally invested in the survival of the ruler. A professional military such as that found in Tunisia is less likely to shoot; a patrimonial military such as that of Libya (or Syria) is more likely to massacre. Alfred C.Stepan explored the dynamics of such decision-making in another great case study, The Military in Politics: Changing Patterns in Brazil.

But while this analysis sheds light on where successful uprisings are likely to occur, it says little about the when. Why were Arab countries seized by a wave of protest this winter, not ten years ago? Specialists have long attributed the quiescence of Arab societies to successful authoritarian repression, which have made organized opposition all but impossible. So why has popular protest proven possible now? The answer can be summed up in two words: social media. Think of the Facebook pages devoted to Muhammad Bouazizi’s self-immolation and the brutalization of Khaled Said by the Egyptian security services. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and smartphones provided the means for coordination and synchronization of thousands of people, in the absence of formal organizational infrastructure. Most important, the anonymity and spontaneity of the media meant they could escape the control of an authoritarian state. More than any other factor, new social media explain why the protesters were able to mobilize now.

But powerful as Facebook no doubt is, it doesn’t explain why the protesters were so peaceful and disciplined in Tahrir Square and elsewhere. This was essential to avoiding the bloodbath that even a professional military would have initiated under provocation. Part of the answer can be found in Gene Sharp’s renowned work on non-violent resistance, most accessibly spelled out in the manifesto he wrote for Burmese dissidents in 1993, From Dictatorship to Democracy: A Conceptual Framework for Liberation. Sharp’s work clearly informed the tactics embraced by the protests’ organizers. Several key organizers, including veterans of the failed April 6 protest last spring, studied his work and modeled their tactics on those of Sharp’s Eastern European disciples, especially in Serbia.

But in the end there is always a measure of mystery about revolution. To paraphrase Tocqueville in his classic study of the French Revolution “without the reasons I have stated, the French Revolution never would have happened . . . but all these reasons together do not manage to explain it.”

Eva Bellin is Myra and Robert Kraft Professor of Arab Politics at Brandeis University.

On Mubarak

BY DANIEL KURTZER

When I was appointed US ambassador to Egypt in 1997, the State Department sent me a transcript of interviews with former US officials who had served in Egypt. Of all the material I had read in graduate school and in the run-up to my appointment—academic books, think tank analyses, newspaper stories—this oral history proved to be the most important. Although all the personnel on both sides had changed by the time I took up my position, the insights—in particular, the cultural and social habits of Egyptians—were still invaluable. I learned, for example, how important funerals and condolence calls are, and by showing up on these occasions, I entered parts of Egyptian society normally closed to Americans. This paid dividends on the job.

I think of this oral history project often because of the place it occupied between the academic and the practical. This is particularly relevant today, with Egypt in upheaval. For most Egypt experts, the events of the past weeks have been something like a crash of our collective hard-drives. Events are moving at such speeds and in such uncertain directions that media commentators have proven almost useless.

This does not mean that academic studies of Egypt are without merit. Richard Mitchell’s pioneering work The Society of the Muslim Brothers was and remains quite important. More recently, the excellent publications of the Carnegie Endowment have helped tune us in to the world of Egypt’s nascent democracy movement.

Unfortunately, no book existed that prepared me for the dealings I had with President Hosni Mubarak. Much had been written about Mubarak’s predecessors, Gamal Abdel Nasser and Anwar Sadat. In fact, they had both written their own autobiographies. But Mubarak was not given to memoirs, nor was he the subject of many books. Thus, in relation to the single biggest challenge an ambassador faces—dealing with the leader of the country—I was left to my own devices.

Of all the epithets being directed at Mubarak these days, the one that is most wrongheaded is “iron-fisted dictator.” Mubarak was no Saddam Hussein, or Hafez al Assad, or Muammar Gaddafi. He would not and did not direct his armed forces to fire on the demonstrators. He knew when the time had come to exit, albeit reluctantly. To be sure, he oversaw a system based on repression of political dissent, and which was authoritarian to the core. But he was not a monster.

To understand Mubarak, in my view, one needs to look at the circumstances of his accession to power, and the challenges he faced during the formative first decade of his rule. Mubarak was sitting next to Sadat on October 6, 1981 when Islamic militants gunned down the president. I wasn’t at the parade but I was stationed in Egypt at the time, and I recall vividly our collective sense that something larger had happened, perhaps an armed Islamist uprising. Sadat had jailed thousands of oppositionists, and in the immediate aftermath of the assassination, Islamists were attacking police stations and other government buildings.

Assuming the presidency at this moment, Mubarak’s first tasks were to restore stability and assure his ability to govern. He must have recalled that both Nasser and Sadat faced early challenges to their leadership. He certainly understood that the two challenges of stability and leadership were inextricably linked. Over the longer term, Mubarak also faced the challenge of keeping Egypt afloat economically. There is much talk today about the $70 billion in US assistance provided over the past thirty years, but it should be remembered that for the first decade of that aid, it only replaced the Arab state subsidies that had been cut off when Egypt signed a peace treaty with Israel. Mubarak made sure to implement the treaty, but it cost Egypt dearly.

Mubarak worked hard over the years to expand the peace. We met often to discuss strategy and tactics. He was not entirely happy with American policy, which he thought was too soft and too beholden to Israeli interests, but he tried to help. At my urging, for example, he was instrumental in persuading a reluctant Yasser Arafat to go to Camp David in 2000, and equally determined not to allow the Clinton administration to walk away from the peace process after the summit failed.

The fact is that thirty years later Egypt is a changed country, and Mubarak deserves some of the credit. It now has a relatively modern infrastructure and an economy that has some free market characteristics, though it is also wracked by cronyism and corruption. Moreover, it has enjoyed a prolonged period without war, not a bad achievement in a tough neighborhood that includes Sudan to the south and Libya to the west. The cost, however, was too high: sustained human rights abuses, severe restrictions on basic freedoms, and a pervasive system of internal spying and fear instilled in those considered dangerous by the regime. Still, Mubarak’s achievements cannot be overlooked.

Steven Cook of the Council on Foreign relations will soon publish a sweeping history of modern Egypt, which will become a must-read for anyone interested in the subject. A similarly sweeping and objective treatment of the Mubarak presidency is also needed.

Daniel Kurtzer has served as US ambassador to Egypt (1997-2001) and to Israel (2001-2005).

Egypt’s Youth Revolution: Some Literary Thoughts

BY MENAHEM MILSON

The images of Cairene masses in Tahrir Square (Liberation Square), with the overwhelming presence of young people, marked the end of an era. Looking at the faces of the demonstrators, I couldn’t help but think of the young protagonists in Alaa al-Aswany’s 2002 Arabic novel The Yacoubian Building. The novel features a diverse gallery of characters, differing in age, social class, and education, who all live in the downtown Cairo building that gives the novel its name. The more affluent of them reside in the building’s spacious apartments, whereas the poor live in cramped shacks on the roof, which in the building’s heyday, during the 1930s and 1940s, were used as storage sheds and laundry rooms. Despite their diverse backgrounds, the characters all share a deep sense of frustration, injustice and misery born of the social and political order prevailing in Egypt.

Taha, a high school student who lives with his parents in one of the roof shacks, aspires to become a police officer and thus rise above the social status of his father, the building’s doorman. His grades clearly make him eligible for the police academy, but when he admits during the interview that his father is a doorman, the admissions committee rejects him as unfit. His letter of complaint to President Mubarak yields nothing but a curt reply affirming that the screening process had been fair, and wishing him luck in another profession. At the university, he gravitates towards a group of religious young men, one of whom influences him to join a clandestine Islamist organization. He is arrested and undergoes brutal interrogations. Eventually he is killed in a terrorist operation in which he and his friends assassinate a police officer.

Taha’s sweetheart, Busayna, also lives in the roof shacks. After her father dies, she must find work in order to help support her younger sisters and brother. She learns that, in order to keep a job—any job—a poor girl like her must provide sexual favors to the boss. She says to Taha: “This country is not ours, Taha. It belongs to those who have money. If you had 20,000 pounds to pay as a bribe, would anyone ask you what your father did for a living?” Embittered and filled with guilt, she leaves Taha and, in the end, marries a debauched bachelor 40 years her senior.

Al-Aswany’s characters rarely mention Mubarak by name. He is referred to as “the Big Man,” who must receive a share of every large business deal requiring official approval. In fact, bribery is the rule in any contact between the citizen and the authorities, at every level.

When I finished reading the novel a few years ago, I wondered: How long can a people so oppressed continue to tolerate the existing order? In al-Aswany’s book, a corrupt politician says:

We have studied the mentality of the Egyptian people well. The Egyptians—God created them submissive to authority. There are peoples who are by nature rebellious. But the Egyptian, he will always bow his head so he can make a living . . . Of all the people in the world, the Egyptians are easiest to rule. Once you assume power, they will surrender to you, grovel before you, and you can do what you like with them.

The events at Tahrir Square have finally belied this theory, which was held not only by Egyptian politicians but also by many experts on Egyptian history.

Another literary work that comes to mind in this context is Najib Mahfuz’s famous novel Children of Gebelawi, originally serialized in 1959 in Egypt’s leading paper Al-Ahram. In a thinly disguised allegory, Mahfuz describes a world abandoned by God, in which injustice and oppression reign supreme. (Egyptian Islamists never forgave Mahfuz his irreverence.) On another level, the novel is a comment on the nature of political power in Egypt, which, according to Mahfuz, is ruled by “those who wield the clubs,” Mahfuz’s description of the officers who have been in power since the 1952 revolution.

Gamal al-Ghithani’s depiction of Egypt’s military regime is equally damning. (Al-Ghitani belongs to the literary generation between Mahfuz and al-Aswany.) His 1974 novel Zayni Barakat tells the story of a cruel and power-hungry police chief in Cairo at the beginning of the 16th century. Zayni Barakat serves the Mamluk sultan, and when the latter is defeated by the Ottoman conquerors, he transfers his loyalty to the new rulers and continues his reign of terror. Al-Ghitani made it no secret that, in describing the oppression and brutality of 16th-century Egypt, he was referring to the regime of the Free Officers under Nasser.

One cannot overlook the fact that, throughout the years since the 1952 coup, the majority of Egyptian writers and intellectuals were acquiescent, and many even willingly served the regime. In his Children of Gebelawi, Mahfuz called them “the poets of the coffee-houses,” who sing the rulers’ praises and avoid any talk “that might embarrass the masters.”

It was remarkable to see how the chief editors of Cairo’s leading papers did an about-face as soon as Mubarak was forced to step down. In a recent television interview, Egyptian poet Ahmed Abd al-Mu’ti al-Higazi said with indignation:

It is inconceivable to support tyranny until January 25, 2011, and then become a liberal as soon as the revolution is successful. I feel sorry for these people, and there are many of them. It’s not just a few journalists . . . they groveled before the regime prior to January 25, and their voices are equally loud today.

The novels of Mahfuz, al-Ghitani, and al-Aswany afford us a deeper understanding of the roots of the Youth Revolution. They cannot, however, answer the two big questions concerning Egypt’s future: whether “those who wield the clubs” will agree to give up the power they have enjoyed for so long and whether Egyptian Islamism will rise or wane.

Menahem Milson is professor of Arabic literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the author of Najib Mahfuz: The Novelist Philosopher of Cairo (St. Martin’s Press). Milson is the co-founder and chairman of the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI).

The Return of Pan-Arabism?

BY ITAMAR RABINOVICH

Hosni Mubarak’s overthrow by an unstructured popular movement sends one back to the classic histories of modern Egypt, P. J. Vatikiotis’ The History of Modern Egypt: From Muhammad Ali to Mubarak and Nadav Safran’s Egypt in Search of Political Community: An Analysis of the Intellectual and Political Evolution of Egypt, 1804-1952. Both, in their different ways, tell the tale of Egypt’s efforts to build a stable, modern polity. Like Albert Habib Hourani in his Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age: 1789-1939 from 1983, they recount the collapse of Egypt’s brief experiment in liberal politics in the inter-war period of the past century. Egypt’s British masters and mentors bear some responsibility for the failure to create a liberal Egypt, but it was swept away by the more powerful forces of Arabism and Islam.

I could go on, but I would rather focus my quest for perspective on the current wave of change on the work of two scholars. Orientalism has been maligned in recent decades but it is difficult to find in the current generation of Middle East scholars those possessed of as profound a knowledge of both medieval Islam and the modern Middle East, as Bernard Lewis. In the current context, I find his The Political Language of Islam particularly helpful. In this book, Lewis drew on his command of Islamic sources and a large number of Middle Eastern and European languages in order to offer us intriguing insights into the way Muslims have thought and communicated about politics. Take a basic concept like “state.” In English and several European languages it implies constancy and stability. In Arabic the term for state is dawla, whose root, dwl, means to turn, rotate, or change. In other words it literally means a revolution. Understanding what Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi and even Wael Ghonim (“the Google man”) mean, and how they are understood by their listeners in Arabic, turns out to be more complicated than just reading the translation of their remarks in the Times or even Ha’aretz.

The second is Fouad Ajami, who was born to a Shiite family in Lebanon and is now the Majid Khadduri Professor of Middle East Studies at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, and Chair of the Working Group on Islamism and the International Order at the Hoover Institution. Ajami became famous in 1978 when he published a Foreign Affairs essay with the title “The End of Pan-Arabism.” Pronouncing the ideology that had dominated Arab politics for half a century dead was considered heresy, but it turned out to be prophetic. Ajami has been required reading ever since. Among his most personal books is The Vanished Imam, which tells the story of the Shiite community in Lebanon and its leader Imam Musa al-Sadr, who disappeared in, of all places, Libya. As the world watches Muammar Gaddafi fighting ruthlessly for his political life, it is instructive to recall how he invited Al Sadr to Libya and probably had him killed at Yasser Arafat’s behest. Curiously, now that Gaddafi is tottering, there are rumors in Lebanon that Al Sadr is actually alive in Libya and may come back to haunt the leadership of Hezbollah. (Not very likely, but an intriguing thought.)

Ajami’s masterwork, The Dream Palace of the Arabs, is a grim portrait of Arab society and politics at the turn of this century. If you read this book now you will not wonder why the region has just been swept by a revolutionary wave but why it didn’t happen much earlier. Ajami’s depiction of the Arab regimes’ management of the peace process with Israel is telling. Under the title “The Orphaned Peace” he describes the way in which Hosni Mubarak kept “the cold peace” with Israel going, while allowing the Arab nationalist and Islamic opposition to rail against Jews and Israelis. But all is relative and as Mubarak was losing his power Israelis latched on to him as the leader who, despite everything, kept the peace, or at least non-belligerency, going.

A final perhaps now-heretical thought: Is pan-Arabism really dead? Or did it recently return to life on the waves of Al-Jazeera? And what might that portend?

Itamar Rabinovich served as Israel’s ambassador to the United States, and as president of Tel Aviv University. He is a Distinguished Global Professor at NYU.

The Democratic Peace Theory

BY MICHAEL WALZER

Almost thirty years ago, Michael Doyle wrote two articles in Philosophy and Public Affairs (“Kant, Liberal Legacies, and Foreign Affairs,” parts I and II, 1983) arguing that liberal states, republics, and democracies don’t go to war with one another. The argument was theoretical (taking off from Kant’s essay on “Perpetual Peace”) and empirical: There really weren’t any such wars. By contrast, there have been many wars, and many kinds of war, just and unjust, between liberal and illiberal states. The zone of peace extends only across the liberal, democratic world, where values are shared and interests mutually accommodated. I think of Doyle’s thesis as one of the relatively few well-founded “findings” of modern political science. It is also a thesis that one would like to be true—and especially now when young rebels across the Arab world are calling for a democratic transformation.

All of Israel’s wars have been fought, as you would expect if Doyle is right, with illiberal and undemocratic states (or illiberal “entities” like Hamas’ Gaza). Lebanon might be an exception, but the writ of Lebanese democracy did not extend to the South, where Hezbollah ruled. At the same time, however, it is also true, as Moshe Arens recently reminded his fellow citizens, that both of Israel’s peace treaties, and all of its cease fires, have been negotiated with illiberal and undemocratic states. Most notably, the peace treaty with Egypt was achieved through the initiative of one dictator (Sadat) and then sustained over three decades by another dictator (Mubarek). I remember being told by Fouad Ajami that this peace, and the later peace with Jordan’s king, “had no legs.” He meant that peace was supported by the heads of these countries but not by the people.

And now in Egypt the head has fallen, and it is at least possible that some form of democracy will follow. Actually, we don’t know what will follow, but let’s assume that after whatever difficulties an imperfect democracy, like all the other democracies, and a relatively liberal democracy, emerges to Israel’s west. Then, Doyle’s thesis will be tested. Will Egypt’s democrats keep the peace with Israel? Or will there be a drift, or a march, toward war?

Curiously, a number of politicians on the Israeli right have been good Doylians, opposing rightists like Moshe Arens, and arguing that a stable peace won’t come to the Middle East so long as Israel’s neighbors are ruled by autocrats, whose policies have little popular support. For some, this has simply been an excuse for avoiding serious negotiations on, say, the Saudi peace proposal, which obviously doesn’t have a liberal or democratic provenance. Now, their bluff has been called, and they are not looking forward to negotiating with a democratic Egypt. But Natan Sharansky has proven that his commitment to the Doyle thesis is serious: In a long interview in The Jerusalem Post, he urged Israelis to welcome the uprisings in the Arab world as (possible) harbingers of peace.

Of course, all this is political science and politics, not physics or math. There are no certainties here. Nor does Doyle’s thesis predict that the citizens of different and often competing democratic states will actually like one another. It is just that they won’t and, in fact, don’t think of war as a way of settling their differences. Consider the example of Germany and Poland today—there is no mutual affection, but no danger of armed conflict either. Why not? It’s not the case that democratic political leaders have great difficulty convincing their citizens to go to war. Rather, in order to do that they have to convince those citizens that the enemy is truly terrible; they have to point to totalitarian communists (as in Vietnam) or to brutal tyrants (like Saddam Hussein). And countries ruled democratically, by politicians who don’t look all that different from you and me, can’t plausibly be described as truly terrible.

Will Israel look less terrible to a democratic Egypt? It is, again, not a sure thing, not even close to a sure thing. But there is at least a possibility that the old Zionist dream of normality will find its realization here, in the peaceful co-existence of (imperfect) democratic states. No doubt, it won’t be a peace of the heart, but if Doyle is right, it will definitely have legs.

Michael Walzer is Professor Emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.

Suggested Reading

History and Polemic: An Exchange

Eric Alterman and Allan Arkush have a heated exchange on Israel, American Jewry, and the role of a historian.

The Fire Now

"As horrific as the Holocaust was, it is firmly in the past. . . . Though I remain horrified by what happened, it is history. Contemporary antisemitism is not. It is about the present. It is what many people are doing, saying, and facing now," writes Deborah Lipstadt in her latest book.

Category Error

What is lost when the books of the Hebrew Bible are read as philosophy?

The Day Turned

One of Lea Goldberg’s last poems was inspired by a prayer from the Yom Kippur liturgy.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In