The Day Turned

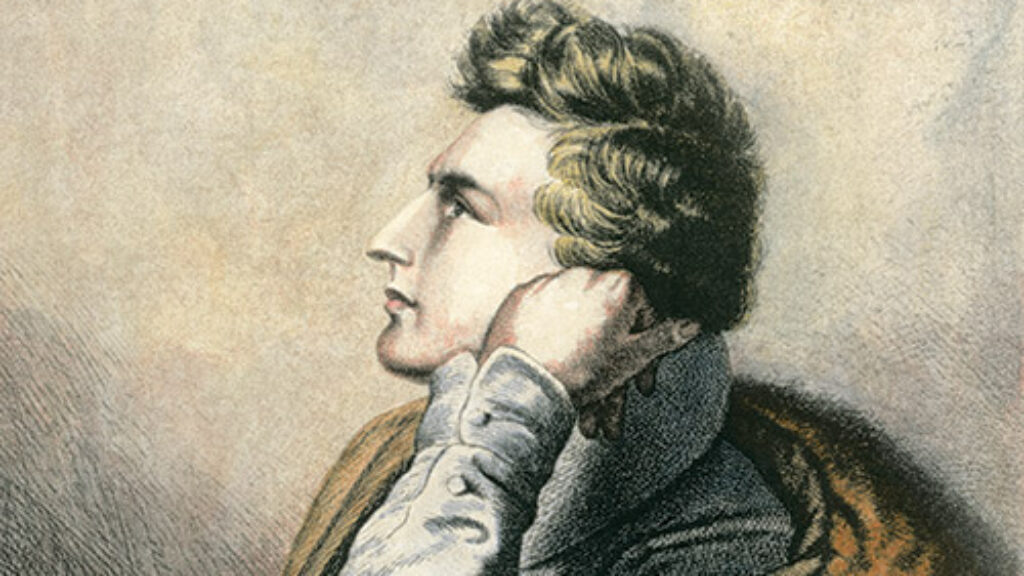

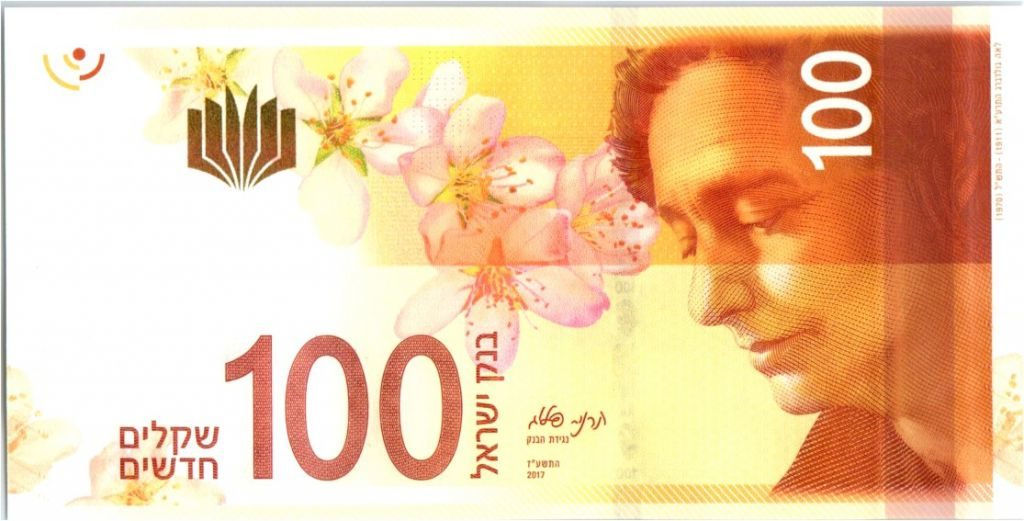

Lea Goldberg was one of the preeminent poets of modern Hebrew letters; decades after her death, her popularity in Israel continues to grow, and she is now even memorialized on Israel’s currency. The eighth poem in Goldberg’s final, posthumously published collection, She’erit Ha-hayyim (translated by me and published in English as On the Surface of Silence: The Last Poems of Lea Goldberg and reviewed for the Jewish Review of Books by Shoshana Olidort) reads as follows:

*

The day turned.

It was not always so.

The day turned its back on me –

my night is an eternal flame.

Now the poems will come

mercilessly.

And I won’t know what to say.

My last love.

Where am I?

So it will be

and so it will always be.

An untitled, fragment text, Goldberg’s poem is built around the phrase “The day turned” (hayom pana), which originates in Jeremiah 6:4: “Alas for us! for the day turned [ki fana hayom], / The shadows of evening grow long.” This phrase is also a refrain from the piyyut “Open a gate for us”—a liturgical poem recited as part of Neilah, the closing prayer service of Yom Kippur.

The secular Goldberg was deeply aware of and connected to Hebrew liturgy in general and this piyyut specifically. In her memoir about the poet Avraham ben Yitzhak (the pen name of Avraham Sonne), she recalls in vivid and emotional detail his moving recitation of the piyyut, which she remembers him naming “one of the most beautiful lyrical poems in Hebrew.”

Goldberg’s utilization of this motif and phrase situates her poem from its very opening line in a sacred space charged with urgency and possibility. However, Goldberg utilizes the well-known liturgical allusion in order to subvert it. “The day turned” becomes “[t]he day turned its back on me,” establishing an image of the speaker rejected, somehow abandoned. She stands alone in a night that is her ner tamid—the eternal flame, the one lamp in the Temple that stays alight always. And it is there, in a night that is, paradoxically, an unextinguished light, that “the poems will come.”

Indeed, it quickly becomes apparent that paradox is a central element of this small and vast poem. The poet—she who is defined by her poetic articulations—strangely describes the poems as coming “mercilessly,” as though there is a burden in being the conduit of poetic expression. And despite this influx of poems, in the very next line the speaker states that she “won’t know what to say.”

Full of unresolved tension, this poem, finally, refuses full explication. It seems as though the poet surrenders herself, in this poem and many others in this singular collection of her final works, to the enigma that is our human life. We struggle with love, with articulation, with feeling alone in the world, with trying to understand our literal and figurative place (“Where am I?” she asks). With the utterly indeterminate assertion that “So it will be / and so it will always be,” the poem ends, as though the questions and the unknowns are, finally, what endure.

Looking for something else to read? We recommend Shoshana Olidort’s review of Rachel Tzvia Back’s translation of Lea Goldberg’s last poems, On the Surface of Silence. Olidort also reviewed Back’s translation of poems by Tuvia Ruebner, In the Illuminated Dark. Readers might also enjoy this introduction to and translation of some poetic fragments from Avraham ben Yizhak and this brief commentary on Emma Lazarus’s 1882 poem for Rosh Hashanah.

Suggested Reading

Dionysus and the Schlemiel

If Judaism was a congenital disease, as Heinrich Heine imagined it was, it is only logical that he would eventually succumb to it.

Hasidic Renewal on the Brink of Destruction

Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, a Hasidic communal leader, and Hillel Zeitlin, a writer who sought to bring Yiddish religious books to a new audience, met on the page, and almost certainly in the Warsaw Ghetto.

“I Am Impossible”: An Exchange Between Jacob Taubes and Arthur A. Cohen

In the summer of 1977, two old friends ran into each other in front of a Paris bookstore and found themselves arguing about Simone Weil, Judaism, and their lives.

The Symbol Catcher

My friends and I took for granted that the connection between the cards and the players they represented wasn’t just arbitrary.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In